Roger Fry and the invention of postimpressionism

If today we know in depth and admire artists such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Paul Cézanne, much of the credit can be attributed to an English art critic and historian who also occasionally served as an artist: Roger Fry (1866 - 1934). To know the beginning of this story, one has to go back as far as January 1910 and go to a specific place: the Cambridge station. Fry has just returned from the United States, where he works as curator of the European painting section at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Or rather: where he officially works, because in fact he is at odds with the museum’s board of trustees, and in particular with its chairman, banker John Pierpont Morgan. Blame differences of views on the management of the collection: Fry’s resignation from his role would come, practically as a mere formality, in February of that year. A few months earlier, the critic had received an offer from Burlington Magazine for an editor’s position, to be shared with art historian Lionel Cust: even without employment at the Met, Fry would therefore not be out of a job. And he really needed it: his wife, Helen Coombe, was suffering from a mental disorder, which in the very early 1910s worsened and forced her to be admitted to a psychiatric clinic, in which she would remain for the rest of her days. In short: the year, for Roger Fry, does not really begin in the best of ways.

|

| Helen Coombe and Roger Fry in 1897 |

Yet he has had an idea that has clearly been on his mind for a while: so he decides to tell it, that morning in January 1910, to his friend Vanessa Bell and her husband, the art critic Clive Bell, on the train from Cambridge to London. The idea, Clive Bell recounts in one of his memoirs, was to “show the English public the works of art of the new French painters.” An idea for which the new friend (Vanessa had introduced him to Fry that very morning) is enthusiastic, not least because he himself had written well about some of these new “revolutionary” painters, such as Cézanne and Gauguin. However, for the time being, the idea remains on paper, and finds no way to materialize: it remains, in essence, a chat between friends on the train.

|

| Roger Fry in the 1910s |

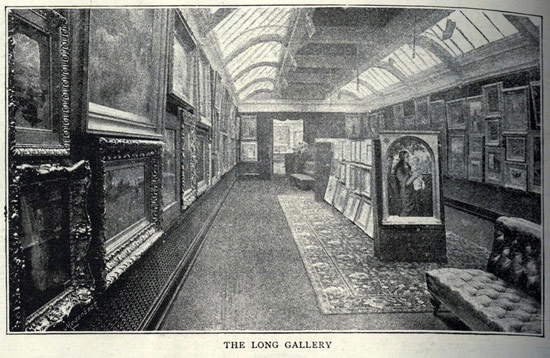

But the opportunity to put the “plan” into action was not long in coming: in September of the same year, the Grafton Galleries Company, the company that runs one of London’s most important exhibition spaces (the Grafton Galleries precisely, also known by its singular form, Grafton Gallery), approached Roger Fry because it had a hole in the exhibition calendar to fill. As per the classic script, the critic is faced with good news and bad news. The good news is that he can finally organize his own exhibition on contemporary French painting, and what’s more, he can do so in a location (as we would say nowadays) of prestige, which had already hosted such landmark exhibitions as the one onImpressionism in 1905, organized by Paul Durand-Ruel, which had brought to London paintings by Manet, Monet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, and even something by Cézanne, or the one of JoaquÃn Sorolla ’s paintings in 1908. The bad news is that Fry has very little time: just a couple of months, because the exhibition will open in November and remain open until January 1911. The critic grabs on the fly a journalist friend of his, Desmond MacCarthy, who has an organizational role in the exhibition, and without wasting any time he travels to France in September 1910 of all places to collect some art. In Paris they met with Clive Bell and began to hunt for the best art dealers and collectors to look for good paintings to exhibit at the Grafton Galleries.

|

| One of the rooms of the Grafton Galleries: the so-called Long Gallery, in 1893 |

|

| Roger Fry, Desmond MacCarthy and Clive Bell in 1933. |

Fry carries with him a list of galleries to visit. There is the gallery of his peer Ambroise Vollard, who was interested in the art of Cézanne, Picasso and the Fauves, and obviously in possession of several works by the aforementioned. There is the Galerie Druet, which holds paintings by Gauguin. There is the new gallery of the very young Daniel Kahnweiler, who is only twenty-six years old but is already beginning to promote the art of the Cubists. In short, there are all the gallerists and collectors who Fry thinks could be useful to the cause. But that’s not all: on September 11, Fry sends Desmond MacCarthy to Munich to meet with German art historian Rudolf Meyer Riefstahl, one of the first academics to deal with the art of Vincent Van Gogh. The hope is that Riefstahl can put Fry in touch with collectors who are in possession of works by the Dutch genius. The hope is well rewarded, because Fry gets the contacts (and the works). The mission to France can be said to be over; Fry returns to England with the knowledge that he has done an excellent job.

|

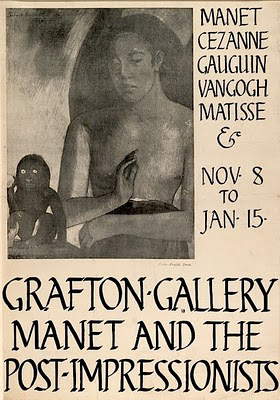

| Poster for the “Manet and the Post-Impressionists” exhibition. |

Having selected the works, it’s up to choose a title for the exhibition. The range of hypotheses is quite wide, because the artists Fry is about to present to the public cover different experiences, often far apart, and a label is needed that can collect them all. "Neo-impressionists“ will not do, because Gauguin had very little that was Impressionist. ”Expressionists“ Fry likes, but the expression does not receive unanimous favor. All that remains is to choose the term ”post-impressionists," which Fry had already introduced, first, in 1906 in one of his essays. After all, the paintings are all by artists who arose afterImpressionism. However, a name familiar to the public is also needed, one that can function somewhat as a “magnet” with which to attract visitors to Grafton Galleries. It is therefore opted to include the name of Manet, an artist at the time already well known in England, considered the father of Impressionism (and therefore his name is also functional in some way to ensure the goodness of the operation from a historical point of view): the idea of using a name of great appeal for an exhibition therefore is not at all a novelty in our days. The title is therefore chosen: it will be Manet and the Post-Impressionists (“Manet and the Post-Impressionists”). This leads to the creation of the poster, the design of the publicity campaign (including several issues in Burlington Magazine), and the convening of the conference to present the exhibition to the press. Finally, on November 8, 1910, the exhibition could open its doors to the public.

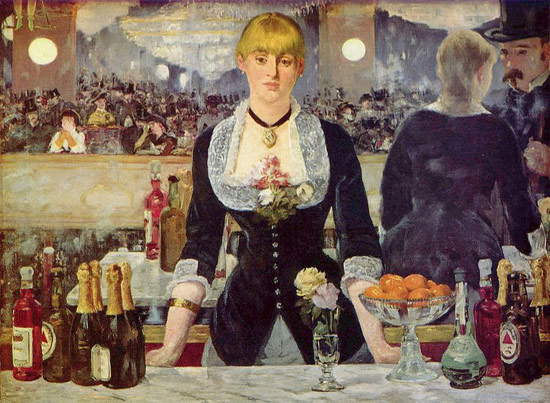

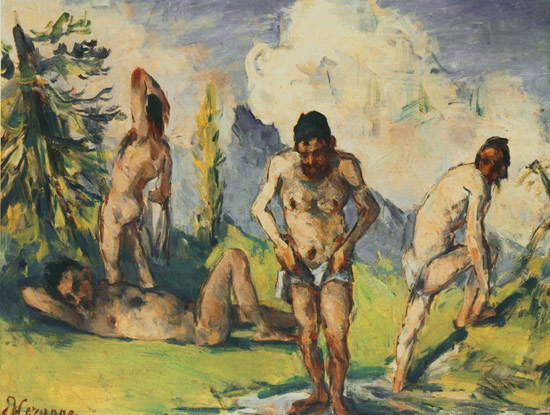

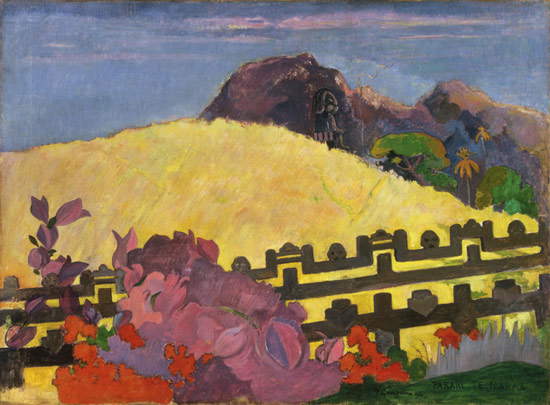

A fairly complete catalog of the paintings in the exhibition has recently been reconstructed. There are eight paintings by Manet: the famous Bar aux Folies-Bergère stands out, which, having already been exhibited in Paris on a couple of occasions, reached London for the first time. Manet’s works are shown at the beginning of the exhibition along with several paintings by Paul Cézanne, who is present with a large array of works, such as Bathers now in Geneva, or L’Estaque finished in 1963 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The visitor is then introduced to the works of Paul Gauguin (there are many, including those relating to his Tahitian period, such as The Sacred Mountain - Parahi te marae, also now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art) and Vincent Van Gogh, displayed together in the same rooms, given the affinities between the two artists. There are nearly thirty works by Van Gogh: these probably include the celebrated Sunflowers now at the National Gallery in London, and there is certainly theSelf-Portrait at the Easel. Then we have Georges Seurat (present with, among other paintings, the Lighthouse of Honfleur) and Paul Signac (with three works) and Henri-Edmond Cross representing pointillisme, and there are also Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Odilon Redon, Maurice Denis, Felix Vallotton.

|

| Édouard Manet, A Bar aux Folies Bergère (1881-1882; oil on canvas, 96 x 130 cm; London, Courtauld Gallery) |

|

| Paul Cézanne, Bathers (1875-1876; oil on canvas, 38 x 45.8 cm; Geneva, Musée d’Art et d’Histoire) |

|

| Paul Gauguin, The Holy Mountain (Parahi te marae) (1892; oil on canvas, 66 x 88.9 cm; Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art) |

|

| Vincent Van Gogh, Self-Portrait at the Easel (1888; oil on canvas, 65 x 51 cm; Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum) |

|

| Georges Seurat, The Lighthouse at Honfleur (1886; oil on canvas, 66.7 x 81.9 cm; Washington, National Gallery of Art) |

The exhibition resulted in great public success, and even some commercial success: sales were not few, and Fry even managed to do much better than a professional dealer like Durand-Ruel, who had failed to sell anything at the 1905 exhibition. However, the enormous upset caused by Fry to the English art scene, which remained anchored in imitation art and never saw works by artists such as Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Matisse, leads many journalists to write fierce criticisms of the exhibition. Much of the public cannot tolerate disruptive novelties such as the violence of Van Gogh’s colors, the brazenness of Matisse’s portraits, and Picasso’s decompositions. Negative reviews thus fell upon the exhibition, even undermining Roger Fry’s own credibility as critic and curator. For Ebenezer Wake Cook of the Pall Mall Gazette, the works are likened to the “production of an insane asylum.” For poet Wilfred Scawen Blunt there are “works of lazy, impotent stupidity” on display and the exhibition is “a pornographic spectacle,” while for art historian Alexander Joseph Finberg the works on display are simply “abortions.” For Robert Ross of the Morning Post, “the emotions of these artists may just be of interest to students of pathology and specialists in abnormality,” and since the press conference had been held on Nov. 5, which is the day of the Dust Conspiracy (the failed plot against James I of England hatched by Guy Fawkes), Ross himself goes so far as to draw comparisons with the 1605 event, asserting that Fry’s exhibition can be considered “a plot to destroy the whole fabric of European painting.” Desmond MacCarthy, in a memoir, also tells of the atmosphere after the exhibition opened: “By presenting the British public with works by Cézanne, Matisse, Seurat, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Picasso, Roger Fry destroyed his reputation as an art critic for a long time. The kinder ones said he was crazy, and moreover remembered that his wife was admitted to an asylum. Most critics declared that Fry was a subverter of morals and art, as well as a brazen promoter of himself.” And Fry himself wrote a letter to his father telling him that a hurricane of criticism had descended on him.

The scholar did not give up, however, and decided to write articles in response to the criticism, defending the motives of the Post-Impressionists, artists who, with their works, did not express what they saw with their eyes, and therefore did not aim to provide a representation of reality: their intent was to express their emotions and their personal vision of reality, so as to make reality take on new and ever-changing meanings. “We must,” Fry wrote, “go on to the discovery of that difficult science which is the science of expressive drawing. We must begin again, and learn once more the ABC of abstract form. That is precisely what these French artists have begun to do, and all with that clear, logical, intense determination, and that absence of all compromise and all regard for secondary matters, which have always nobly distinguished French genius.” However, despite the many criticisms, Roger Fry could count on the support of friends who believed in his work (above all Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell’s sister), and the scholar decided, heedless of everything, to organize a new exhibition of the Post-Impressionists in 1912, continuing to believe that English figurative culture should update itself on the experiences coming from France and the rest of Europe.

The articles in defense of the Post-Impressionists and, in general, the essays related to exhibitions of the Post-Impressionists, are considered today among the fundamental writings for understanding the art of Gauguin, Van Gogh, Seurat, Cézanne, Matisse and colleagues. And the exhibition is believed to have been the event that actually laid the groundwork for the consecration of the Post-Impressionists.It may be too much to say that without Manet and the Post-Impressionists, art history would have taken a different turn, but the exhibition certainly sparked several positive effects, helping to substantially update the British art milieu and ensuring that Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh and others began to be taken into account as artists of fundamental importance. And more than a hundred years later, we can say that the remark that appeared in The Athenaeum magazine shortly after the opening of the exhibition curated by Roger Fry proved to be entirely well-founded: “1910 will be remembered in our art history as the year of the post-impressionists.”

Reference bibliography

- Charles Molesworth, The Capitalist and the Critic: J.P. Morgan, Roger Fry, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, University of Texas Press, 2016

- Anna Gruetzner Robins, Manet and the Post-Impressionists: a checklist of exhibits in The Burlington Magazine, 2010, vol. 152 no. 1293, pp. 782-793

- Frances Spalding, Roger Fry, Art and Life, Black Dog Books, 2n edition, 1999

- Christopher Reed, A Roger Fry Reader, Chicago University Press, 1996

- Stanford Patrick Rosenbaum, The Bloomsbury Group: A Collection of Memoirs and Commentary, University of Toronto Press, 1995

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.