Renoir, Van Gogh and Picasso: Detroit portraits compared

If we were to imagine standing next to great artists such as Renoir, Van Gogh and Picasso and being able to ask them in what way they were preparing to paint a portrait, we would surely get rather different, if not even antithetical, considerations. In the span of a century, in fact, that is, from the second half of the nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth century, there followed various currents and therefore different ways of painting, which today are highly appreciated by the general public but which, on the contrary, found little acceptance in their time: one thinks ofImpressionism and the stir that ensued when the traditional canons of art and good painting were set aside in pursuit of the sense of freedom of painting in the open air, amid the sound of the wind echoing through tree canopies and blades of grass and the bright sun warming the painter’s face and body. No more painting inside artists’ studios, but directly in the place that was the subject of the painting.

However, the Impressionists did not always depict landscapes or people within landscapes; in fact, scenes of everyday life were also very common, in which the characters depicted were caught in natural and casual poses, in habitual actions of everyday life, often giving the viewer the impression that they did not realize they were being portrayed, as when someone takes a photograph of us without us noticing: the result is one of absolute naturalness and spontaneity. One example is Pierre Auguste Renoir’s Woman in an Armchair, a work created by the artist in 1874, the year of the first Impressionist exhibition, and preserved at the Detroit Institute of Arts. The woman with brown hair and small bangs framing her face appears in a relaxed pose, with her back fully leaning against the armchair on which she is seated and her arms crossed under her prosperous breasts contained by a white blouse that leaves her shoulders uncovered; from her gaze she seems pensive, absorbed in her thoughts, or she seems to be listening to someone standing next to her: in fact, her eyes are not looking at the viewer or the artist who is portraying her, but are turned to her left. The light that illuminates her face and cleavage, her slightly flushed cheeks, and her clothing suggest that the portrait was taken on a beautiful warm spring or summer sunny day.

|

| Pierre Auguste Renoir, Woman in an Armchair (1874; oil on canvas, 61 x 50.5 cm; Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts) |

If we had asked Renoir how he set about to portray a person, lo and behold, he would probably have replied that his intention was to give greater prominence to the subject on which he wanted to draw attention, illuminating it with a natural light and defining the stroke more precisely, while the background was the result of quick, undefined brushstrokes, in which the colors overlapped, blended, without precise contours, giving a sense of evanescence to what surrounded the subject on which the observer would focus his gaze.

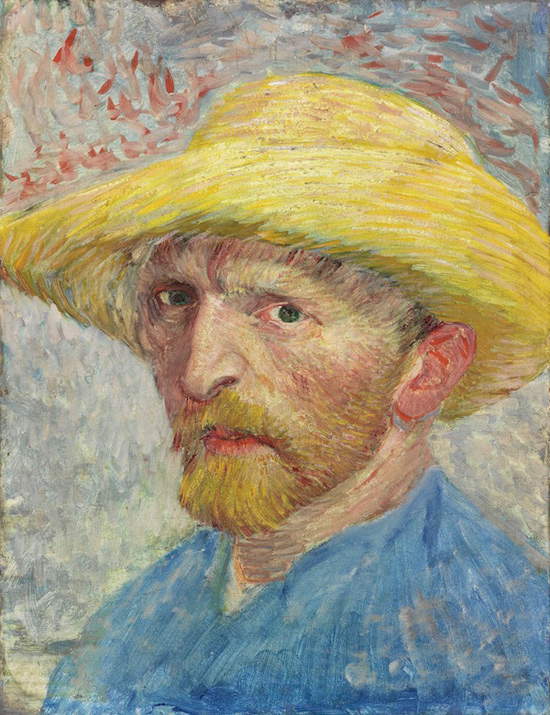

Only thirteen years later, Vincent Van Gogh would create his famous Self-Portrait, also preserved at the Detroit Institute of Arts. It fell to this very museum to have the honor of being the first among American museums to own a painting by the artist: it was indeed the 1887Self-Portrait, which the institute acquired in 1922.

|

| An excerpt from Van Gogh’s letter to Livens. |

Around the time the work was completed, Van Gogh had moved at the invitation of his brother Theo to Paris, where he had come into contact with the Impressionists: he admired the nudes of Degas, the landscapes of Monet. Fascinated by these artists, he gave prominence in his paintings to light and color, but the spirit was already no longer Impressionist: Van Gogh conveyed in his self-portraits all the suffering he felt because of unhappy love affairs and his unfavorable economic conditions. According to what we read in a letter written by Van Gogh himself to the English painter Horace Livens, whom he had met in Antwerp, due to the lack of financial means to be able to pay for models for portraits, he began to make some self-portraits and paint flowers: in these works the artist made an in-depth study of colors. Thus Van Gogh wrote, in English, to his friend: I have made a series of color studies in painting simply flowers, red poppies, blue corn flowers and myosotys, white and rose roses, yellow chrysanthemums seeking oppositions of blue with orange, red & green, yellow and violet, seeking les tons rompus et neutres to harmonise brutal extremes (I have made a series of color studies in painting simply flowers, red poppies, cornflowers and blue forget-me-nots, white and pink roses, yellow chrysanthemums seeking the contrasts between blue and orange, red and green, yellow and violet, seeking the tons rompus and neutral colors to harmonize them with the more extreme and brutal colors).

Van Gogh’s paintings do not convey Impressionist joie de vivre, but are emblematic of his torments and loneliness. The one of 1887 is a self-portrait in the mirror and his gaze is fixed and inquiring; against an indefinite background the bright yellow of his straw hat and beard stand out, and his face seems to come out of the canvas. A light given, therefore, by bright colors spread with marked and clearly visible strokes-a peculiarity of Van Gogh’s way of painting, who often even squeezed color from the tube directly onto the canvas.

|

| Vincent Van Gogh, Self-Portrait (1887; oil on canvas, 52 x 43 cm; Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts) |

Almost a century after Renoir’s Woman in an Armchair, Pablo Picasso, almost 80 years old, made Sitting Woman in 1960, now preserved, like the previous two paintings, at the Detroit Institute of Arts. The way of portraiture and painting had changed considerably: if in the Impressionist portrait the woman portrayed was illuminated by sunlight and depicted exactly as she was in reality, in Picasso’s work we are witnessing another revolution in art; we are in the midst of cubism: the forms of the face and body are broken down and recomposed so that they can be seen at the same time from multiple angles. No one will miss the composition of the woman’s face in the 1960 painting: as many as three angles appear side by side! But even some parts, such as the hands, appear unreal, noticeably disproportionate to the rest of the body.

|

| Pablo Picasso, Seated Woman (1960; oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm; Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts) |

Markedly different we note are the colors Picasso used compared to both Renoir and Van Gogh: while the latter two favored light hues and bright colors, the former favored dark hues or paintings almost entirely in black and white, as in the case of his Seated Woman, in which the only exception is the burgundy-red of the dress. The contours and lines are also marked in contrast to the other two paintings.

Radical changes that profoundly marked the history of art in the space of barely a century. The portraits by Renoir, Van Gogh and Picasso mentioned here are on display until April 10 at the Palazzo Ducale in Genoa as part of the exhibition From the Impressionists to Picasso. Masterpieces from the Detroit Institute of Arts.

|

| The three portraits compared. We have tried to respect the actual proportions of the paintings |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.