Reflection on Madrid's Ecce Homo: it is not by Caravaggio

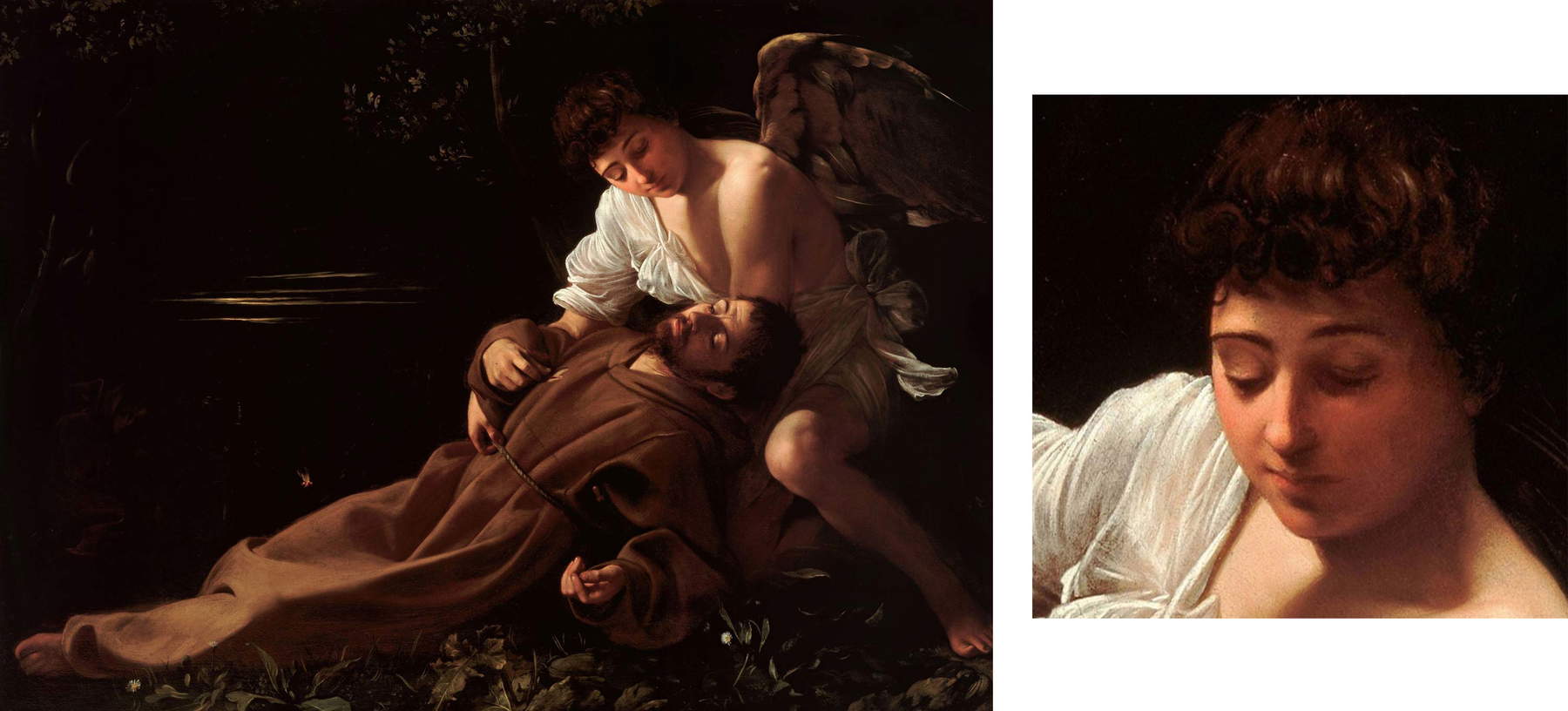

Of theEcce Homo (Fig. 1) presented as a work by an unknown follower of Ribera in a sale on April 8, 2021, by the Ansorena Auction House in Madrid, which caused a great uproar in the art world almost uniformly inclined to recognize it as a masterpiece by Caravaggio, it was was finally able to see the results of the removal, through judicious cleaning, of the dark patina of grime and old varnish, thanks to a photograph of excellent quality, in my opinion more than enough to arouse an impression far removed from the promise the work had seemed to hold. It is undoubtedly a fine painting, but totally lacking in Caravaggio’s dramatic vigor and the emotional tension inherent in the most tragic event in history, destined to upset the course of humanity.

Where is the unfailing manifestation of Caravaggesque research, which finds its form more in the shadows than in the lights, although it is then the latter, avoiding all obstacles, that break in on the former in a strenuous competition that already reflects in its intentions the tragic event it is intended to revive? Impossible now in the moderate chiaroscuro and in the full clarity of the forms to recognize the revolutionary seed of a painting destined to render obsolete figurative canons of an already glorious past, but now oriented to express themselves in terms of devotional nobility, in manners as in subjects, rather than in a search for the crudest truth.

Having removed the dark patina that seemed to dramatically bring out from a deep and disturbing darkness faces distorted by emotion, the cleaning of the work was merciless to those, myself among the victims, who had already believed in the exciting discovery of a new Caravaggio masterpiece.

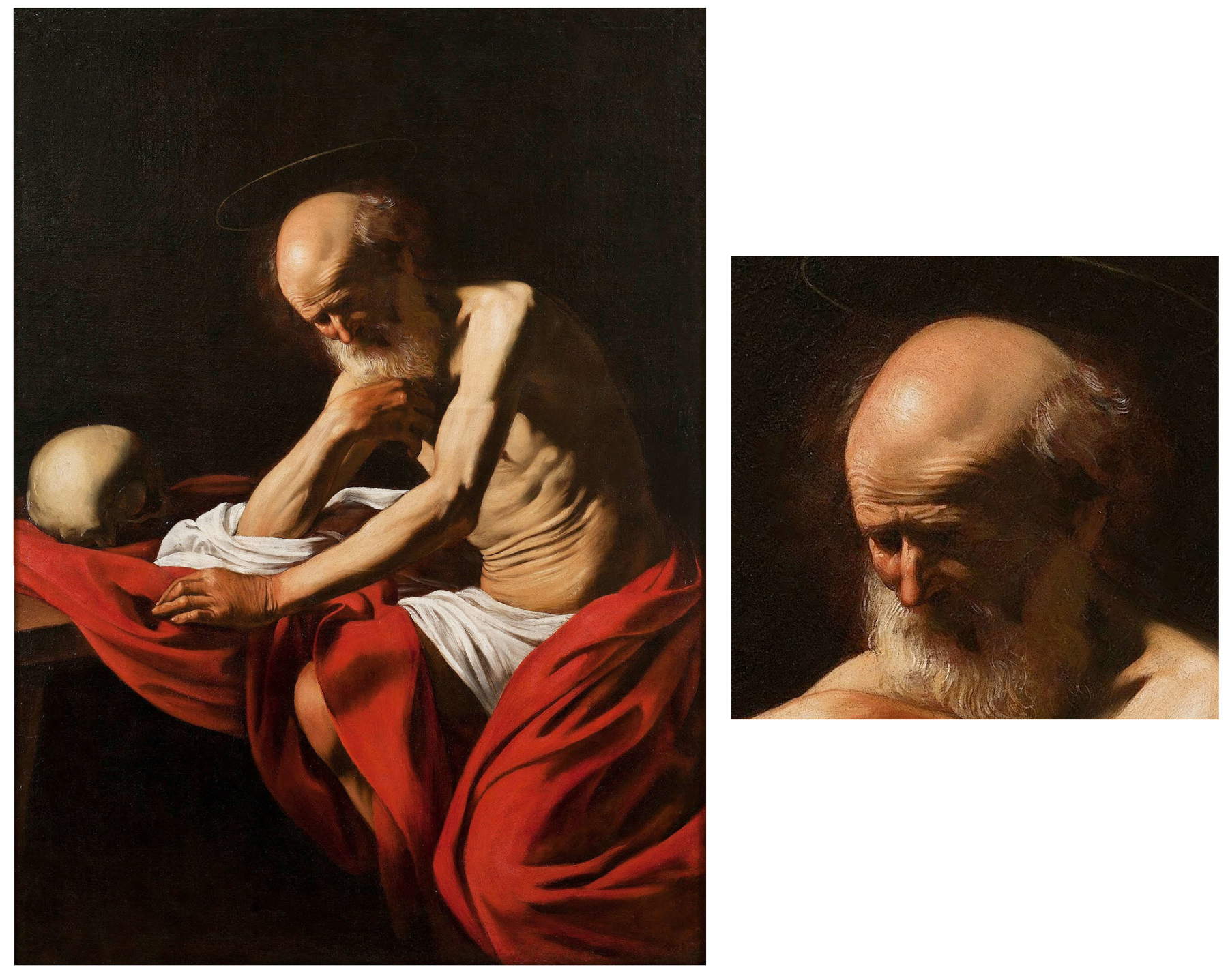

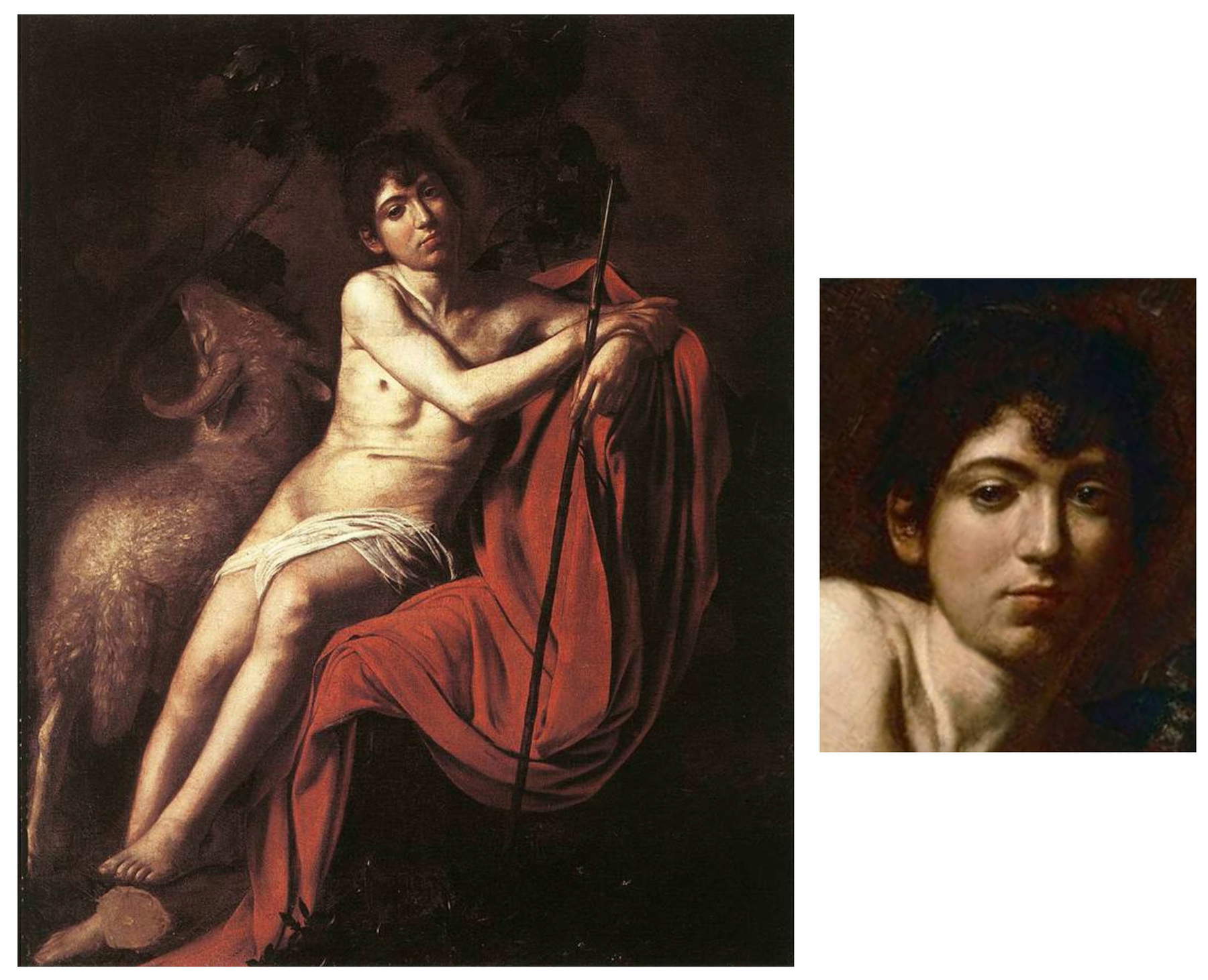

Today what can be seen in the work (Fig. 2) decisively changes the impression it had aroused: profoundly changed the expressive intensity and dramatic tension of the composition and much contained its emotional pathos. Far from deeply troubled, but only vaguely saddened without too much empathic participation Pilate’s face. Discounted is the gesture of the hands, which, forced by the limited space available, rather than pointing directly toward the captive Christ in pointing him out to the people, seem rather oriented toward showing something to his left. Considering Caravaggio’s mastery, even in his own more complex works, to create the most convincing compositional realism in the always studied placement of each character and credibility in their attitude, one can be sure that he would have resorted rather to a different format, so as not to deflect from the full realization of his own realistic pictorial project. No longer as hopelessly hallucinated as expected now appears the expression of the young man behind Christ, the handsome face partially veiled by a shadow that conceals nothing of his features, the mouth no longer wide open in a gruesome sense of horror, but whose restrained dramatic expressiveness does not go beyond that assimilated to the proclamation of a public proclamation: more a mere henchman than a ruthless executioner.

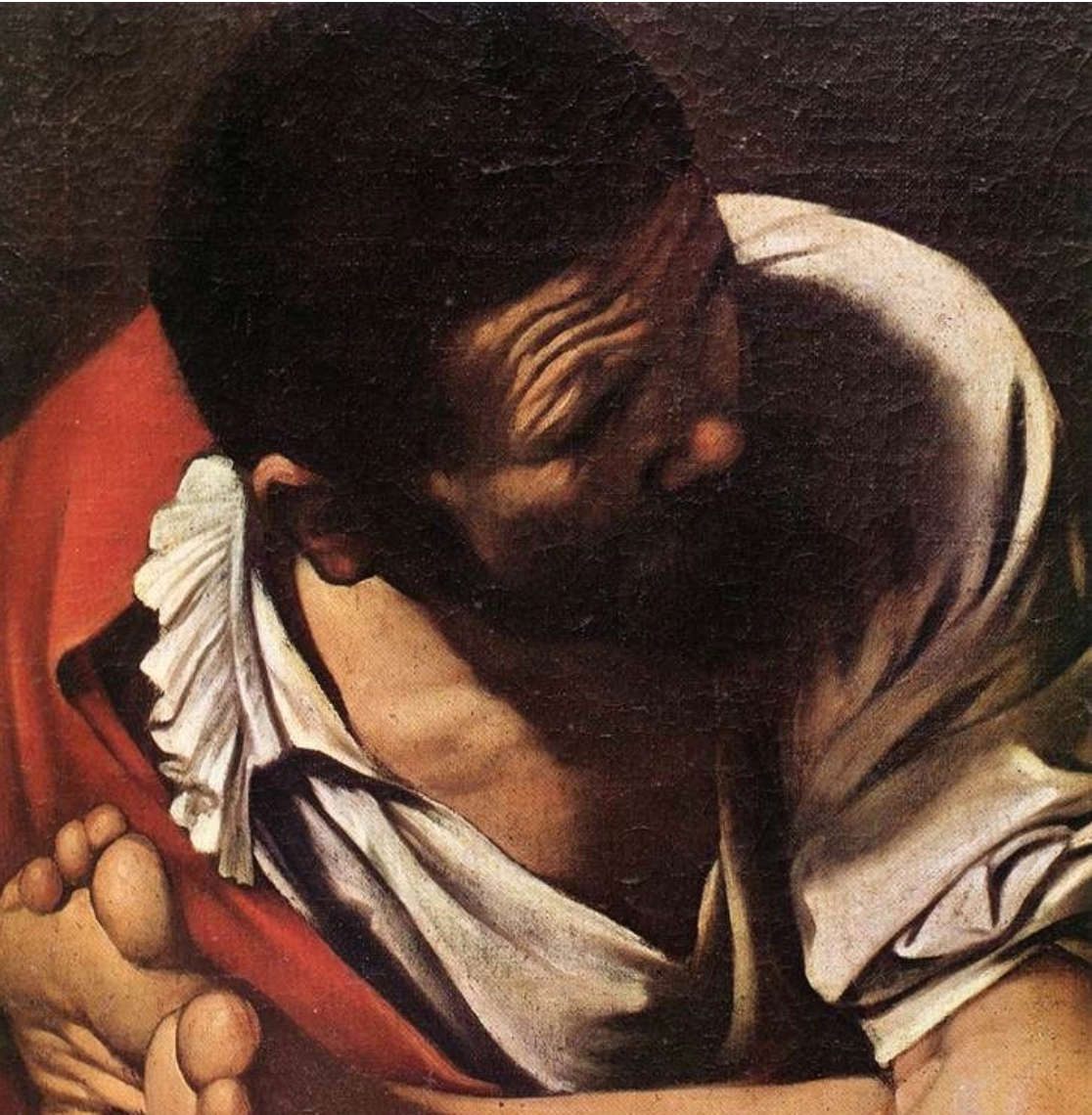

Perhaps, under the suggestion of Caravaggesque images such as the Medusa in the Uffizi, as happened to even occasional followers of Caravaggio, one for all the Genoese Orazio De Ferrari, one would have expected an expression of much more extreme dramatic intensity (Figs. 3-4). As for Jesus’ expression, rather than mirroring the atrocious suffering he endured, the resigned sadness for a moral rather than physical pain shines through.

But above all, it should be noted how the conformation of his face shows clear weaknesses in modeling that are impossible to attribute to Caravaggio. No longer concealed by the dark patina of the old paints, they now appear in resounding evidence, despite the fact that the tilt of the head may perhaps still mitigate the visual disturbance a little.

By straightening it vertically, with a simple digital processing, it is evident how Christ’s face is asymmetrically deformed to the point that even his eyes are decidedly out of alignment, as are, moreover, the entire right half in relation to the left, so that even the wrinkles that furrow his forehead suffer a consequent unnatural declination.

That the author of the painting was subject to these weaknesses in correctly modeling the somatic features of a face in the correct perspective of a foreshortening is also evident in the right ear inserted into Christ’s head at an impossible oblique angle. And modeling weaknesses are naturally found in Pilate’s face as well, certifying a gap in the author’s modus operandi. Caravaggio’s perfect knowledge of the human body and absolute mastery of perspective can always be verified in each of his works and at any time of his activity, whatever the various postures of the characters he depicts.

The work is intended to depict the fateful moment when the life or death of a character of enormous prominence and equally widespread popularity is decided, who, amid extreme feelings of hate and love, dramatically divided the entire population of Judea into opposing factions. Of the numerous versions of the episode painted by Caravaggio, according to the testimony of historical records, none has come down to us beyond the single Genoese example in the Palazzo Bianco.

However, considering the painter’s works also related to the theme of the martyrdom of Christ and the strong dramatic tension that characterizes them, theEcce Homo that has just been rediscovered stands out for its interpretation under the banner of an expressive moderation that really does not seem to correspond to the dramatic tension expected of Caravaggio.

The subject offers an opportunity for a contribution in favor of recognizing as an autograph work by Caravaggio theEcce Homo in the Genoese museum of Palazzo Bianco (Fig. 14), which the discovery in Madrid, seemed likely to downgrade, giving definitive credence to not a few doubts expressed by some scholars about its belonging to the painter.

It is now well established that neither work can be placed in relation to the commission given between 1605 and 1607 by the Roman nobleman Massimo Massimi to Caravaggio, Cigoli and Passignano of three paintings depicting theEcce Homo, which must have had by contract the same measurements, now verifiable in the only surviving example painted by Cigoli, which passed in time to the Pitti Palace and which turn out to be 175 x135 cm, thus much larger than both the Genoa and Madrid paintings.

A certain distance from what might be expected of Caravaggio for an interpretation of the episode centered on a more crude brutality of expression probably influenced the doubts that still persist about the attribution of the Genoese exemplar, which, although always credited with high executive quality, has seemed to some to be alien to the painter’s usual figurative realism. An aspect that certainly cannot have escaped Roberto Longhi, whose judgment became peremptory in favor of the work’s certain belonging to Caravaggio himself, only after the cleaning carried out by Pico Cellini had made its original quality visible, removing the obscure centuries-old patina of grime and old oxidized varnish that had caused him initial perplexity. Previously, numerous examples of the same composition had been considered by Longhi to be modest faithful copies taken from a lost original by the Lombard master, beginning with the one belonging to the Museo Nazionale in Messina exhibited in the historic 1951 Milan exhibition. It was therefore a judgment matured after elaborate reflection by the great scholar, who was the first to understand the enormous scope of the art of a brilliant painter, the greatest of his time, almost forgotten in centuries diverted by prejudice, sectarianism and cultural fundamentalism. Beyond the ability to recognize and restore to Caravaggio lying works that had been ignored or forgotten, at a time when the means of comparison and the tools to support memory consisted solely of black-and-white photographs, Longhi must above all be credited with having understood and penetrated Caravaggio’s creative spirit with the depth afforded by a critical talent that was and remains unmatched today.

Evidently, it must not have seemed so misleading to him the different interpretation of an episode also liable to alternative emotions, no longer expressive of masculine brutality but directed to arouse feelings of piety equally truthful, although unheard of in the more usual activity of the painter.

After this heartfelt tribute to the man who was my teacher and mentor, I think it only fair to honor his insight concerning theEcce Homo in Palazzo Bianco with a few considerations that seem to me as appropriate as ever.

Although in the pictorial aspect the quality of the work has never been questioned by anyone, unusually after more than seventy years since its discovery no alternative hypothesis has ever been formulated about a possible author of the work, despite the fact that the numerous existing copies point to an artist of established craft and consequent notoriety. It would perhaps be time to resign ourselves to the idea that no other works by this unknown painter have survived the passage of centuries, unless we opt for the hypothesis, more reasonable in my opinion, that a certain atypicality has not allowed a unanimous consensus in recognizing in it ways referable to Caravaggio. It has been agreed that Pilate’s face has the appearance of an obvious portrait, and several scholars have taken turns in suggesting the possibility that it is the self-portrait of Caravaggio himself, while others have seen in it a more convincing resemblance to the Andrea Doria (Fig. 15), painted by Sebastiano del Piombo in Rome in 1526 by order of Clement VII, when the admiral became supreme commander of the papal fleet.

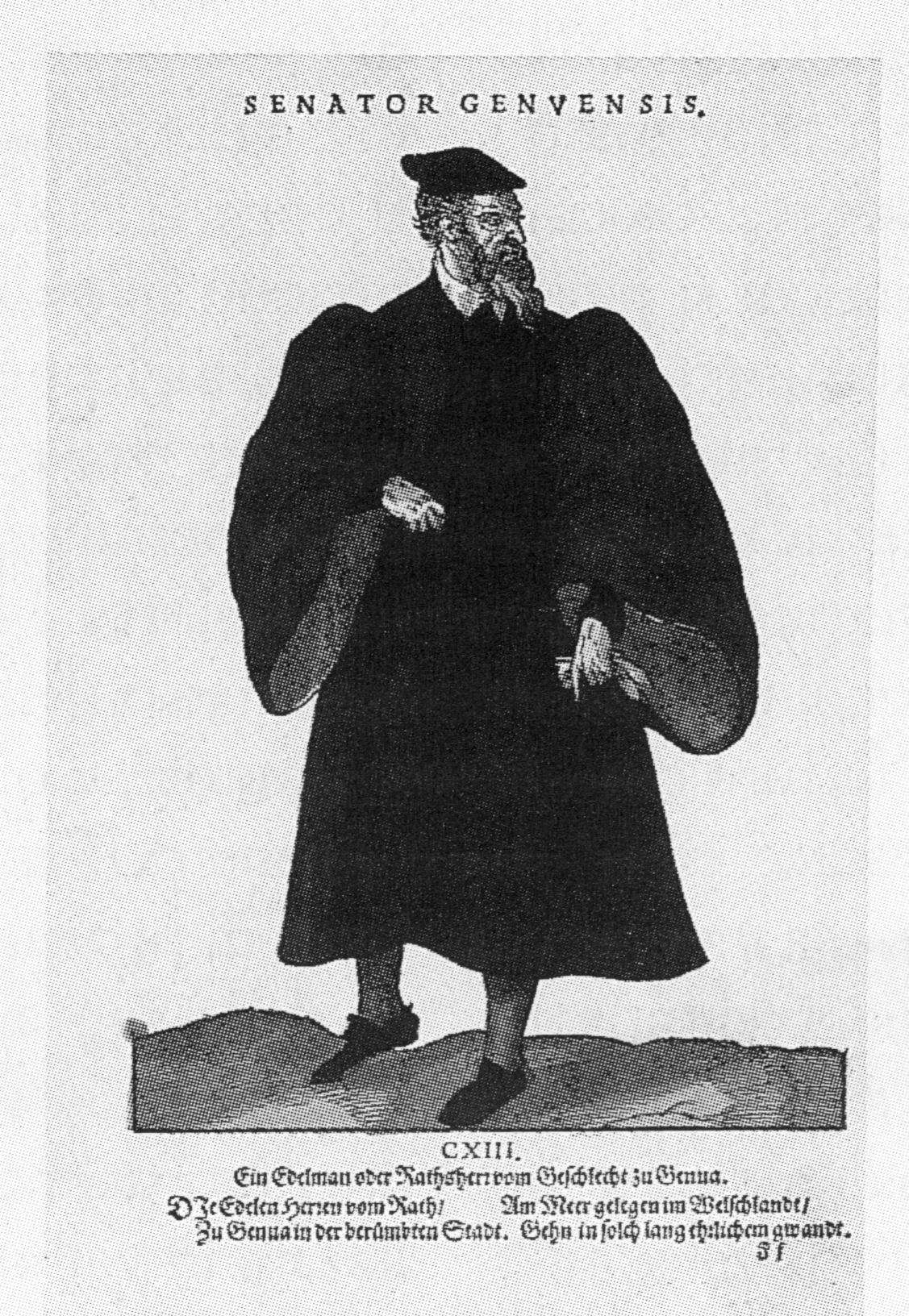

The identification has, however, remained without significant follow-up, but it is still surprising that no one has ever detected in it the obvious anomaly of an absolutely unprecedented attire for a character always depicted by every painter, in every age, in oriental garb, conforming to the territory the scene of the story.

It is not only the physiognomic resemblance and posture that suggest the appropriate juxtaposition, but it is above all that unusual black robe and characteristic biretta worn by Pilate. Garments that constituted the official attire of the senators of the Genoese Republic (Fig. 16), worn in fact in the portrait also by Andrea Doria, who, as is well known, after reforming the constitution of the Genoese Republic, always refused the office of Doge, retaining only his post as senator of the Republic in a more decisive controlling body that constituted the Priory of the Mayors, ultimately the true center of power.

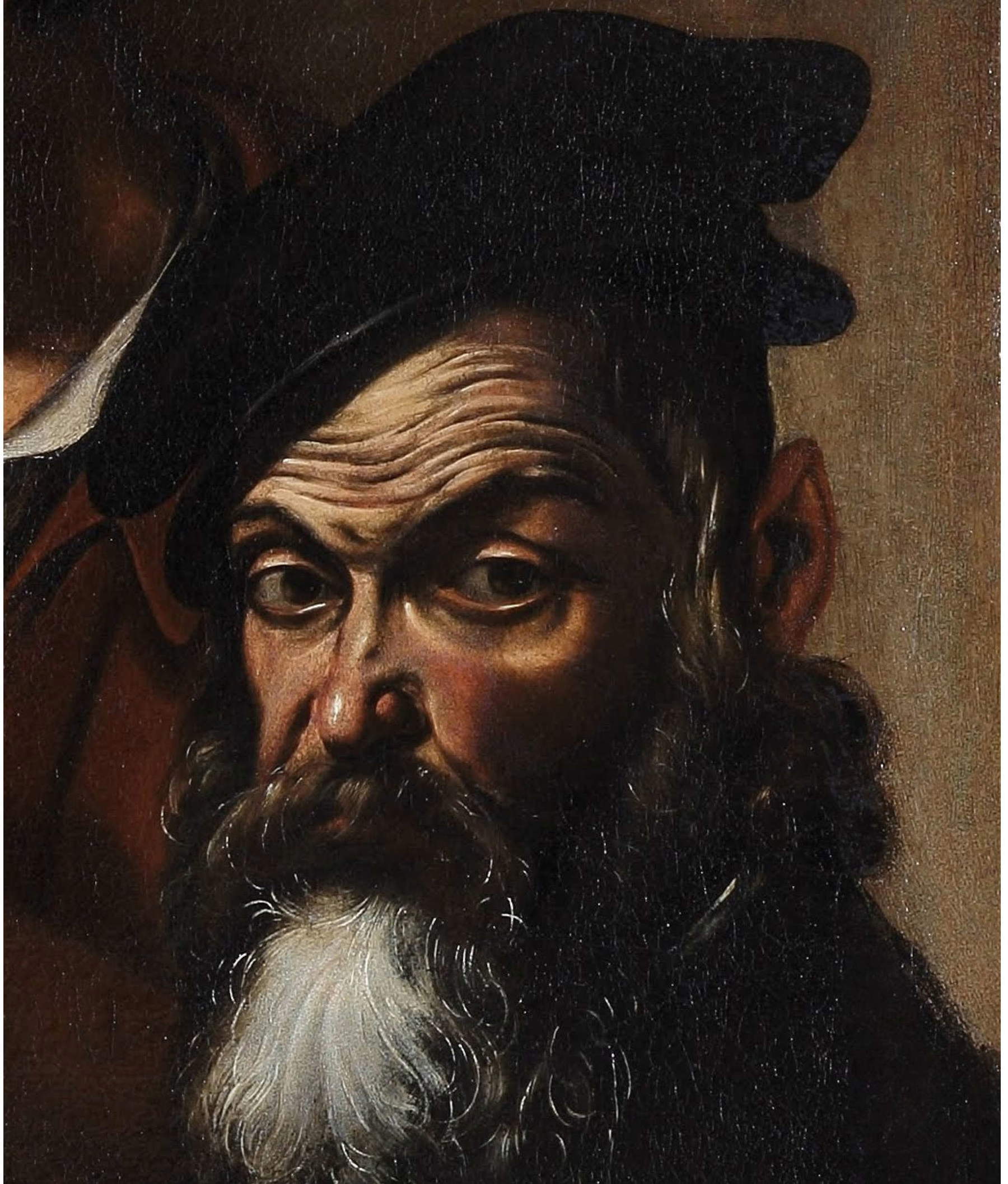

If the relationship of the figure of Pilate to Sebastiano del Piombo’s Andrea Doria can be considered convincing at this point, however, its different facial expression should be noted, where the haughty serenity of the great admiral, is replaced by the frowning gaze of the Roman prefect of Galilee, called to the unwelcome task of issuing a blatantly dastardly death sentence. The raised eyebrows furrowing deep wrinkles on his forehead express a kind of skepticism and incredulous disapproval, as he asks the people in turmoil, what danger could such a visibly meek and defenseless individual as the one whose crucifixion was demanded could possibly pose. And appropriately Jesus is indeed depicted there of unusually puny constitution, downcast-eyed, humiliated and surrendered, while the jailer behind him, his head slightly recumbent, seems intent on covering his shoulders with charitable delicacy rather than insolent disparaging intent.

It is ultimately a work of a singularly compassionate character, in which all the characters uniquely play their part, each according to the role assigned to him by the painter, achieving a convincing expressive reality that, although of a character unprecedented in Caravaggio, nevertheless cannot be considered extraneous to his search for crucial truth.

Such a pietistic interpretation of the subject basically corresponds to a correct reading of what is reported by the evangelists, who emphasize Pilate’s initial reticence in the face of the peremptory claim of the Sadducees, then dominant among the Jewish population, to condemn Jesus to crucifixion. A claim to which Pilate ended up yielding, more out of cowardice than conviction, consigning himself to history as the one who “washed his hands of it” condemned the son of God to an atrocious death.

What could have induced Caravaggio to depict Andrea Doria in those execrated guise remains hard to explain, especially in the absence of any information on the provenance of the work, which has arrived unknown how in the deposits of Palazzo Bianco. A possible hypothesis could be formulated considering that Caravaggio’s greatest admirers and protectors belonged to the papal nobility, among whom at that time the bad memory of Andrea Doria was probably still alive in Rome.

It is likely that in much of the aristocracy still harbored a deep-seated feeling of hatred toward the great Genoese admiral, in the memory of when he had abruptly left the command of the papal fleet and broken thealliance with the papist French king Francis I, to go into the service of the great enemy Charles V, who had already been made responsible for unleashing hordes of lansquenets against the city in an inhuman work of pillage and devastation, the consequences of which were still to persist to some extent.

Leaving aside, however, to push the imagination further into conjectures unsupported by documentary news, one cannot, in my opinion, fail to decisively reaffirm the work’s high level of quality and, with at least one connoisseurship quote, resort to one of those clear “Morellian” signs useful in strengthening the conviction of its belonging to Caravaggio’s more mature time. Returning to the face of Pilate-Andrea Doria, the distinctly characteristic way of accentuating its expressive force, furrowing deep parallel wrinkles that run in sinusoidal traces across his forehead pressed together by the lifting of his eyebrows, constitutes a kind of wholly typical and unmistakably unique “styleme” that is often repeated in Caravaggio’s works and so marked only in his own, among so many Caravaggesque followings.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.