Raphael was the first superintendent in history. The letter to Leo X

Many art historians like to define the great Raphael Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520) as the first superintendent in history, and it is not a stretch to say that his figure constitutes one of the fulcrums of the history of monument protection in Italy. We need to go back to August 27, 1515: on that day, Pope Leo X (Florence, 1475 - Rome, 1521), the pontiff who would later be eternalized by Urbino in a magnificent portrait now in the Uffizi, was appointed praefectus marmorum et lapidum omnium. To the letter, Raphael was therefore the “prefect of all marbles and tombstones”: in practice, his task was to search Rome and its environs for marbles to be used in the building site of St. Peter’s basilica, while making sure that ancient materials, epigraphs and fragments found in the city’s territory were saved. Each find was to be carefully studied by an expert, who would decree its fate: in fact, the pope and Raphael were well aware of the value of evidence from the past, and it could not be allowed to be destroyed or reused as building materials. Especially since, at the time, the trade in antiquities was flourishing and the practice of reusing fragments of ancient buildings was the order of the day: here, then, it becomes easy to guess what the importance of the position assumed by Raphael was.

The divine painter nurtured a great love for antiquity. A connoisseur of the monuments of ancient Rome, a passionate architect of Vitruvius (to the point of promoting the production of a vernacular edition of De architectura, translated and edited by the Ravenna humanist Fabio Calvo), a passionate scholar of the structures of the buildings of the Rome of the emperors, he was commissioned by Leo X to draw up a map of the ancient city and its monuments, based on a precise measurement of the ruins and classification of the vestiges of classical Rome, which would in turn be the basis for a philological reconstruction of what had been lost. The project never came to fruition, because his untimely death at the age of only thirty-seven deprived the world of one of the greatest artists of all time, but it remains a fundamental document for understanding the reasons for that project, for deriving Raphael’s ideas about antiquity, for grasping all his ardor in defending ancient monuments and his disdain for those who were responsible for their destruction and did not prevent them from being damaged even in modern times. The document has gone down in history as the Letter to Leo X: it is a text whose authorship is still uncertain, since we do not have the original drafting of the text, but we can assume that the basic idea and technical parts can be attributed to Raphael, while the elaboration in literary form could be assigned to the Mantuan humanist Baldassarre Castiglione (Casatico, 1478 - Toledo, 1529), who helped Raphael, to whom the intellectual authorship of the document must be acknowledged in any case, to write a text in a form suitable for a high-level interlocutor such as Pope Leo X. The missive probably dates from September-November 1519: this is the dating proposed by Francesco Paolo Di Teodoro, a scholar known for his long commitment to minutely analyzing the letter.

Art historian Valerio Terraroli edited its most recent edition for Skira(Raphael. Letter to Pope Leo X, Skira, 2020): according to the scholar, the letter “represents one of the highest moments of Renaissance culture and of the identification in classical antiquity of the ideal model, both from the formal and from the technical-operational point of view,” and at the same time reveals between the lines “the assumption of responsibility by Raphael and his contemporary humanists, starting with Leo X, for the preservation of a unique, fragmentary and threatened monumental heritage, in the name of the transmission of memory and the passing of the baton to the new age.” As mentioned, we do not have the original text, but the letter is preserved in four written sources: a transcription formerly kept in the Castiglione archive in Mantua and purchased in 2016 by the state (today it is kept in theState Archives in Mantua), a manuscript from Munich that is, however, derived from the Mantuan text, a version printed in Padua in the 18th century and based on a manuscript copy of which nothing else is known, and a transcription kept in a collection of copies of Castiglione’s letters kept in a private collection in Mantua.

|

| Raphael, Self-Portrait (1506-1508; oil on poplar panel; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings). Photographic Cabinet of the Uffizi Galleries - On concession of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism. |

|

| Raphael, Portrait of Leo X between Cardinals Giulio de Medici and Luigi de Rossi (1518-1519; oil on panel; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Statues and Paintings Gallery) |

|

| Raphael, Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (1513; oil on canvas; Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures). © Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN Grand Palais / Angèle Dequier |

Terraroli, while briefly recalling the critical debate around the authorship of the work, pointed out how, in 2010, scholar Michel Paoli emphasized the unitary structure of the Lettera “which makes it, therefore, a methodological text, with a design objective, that of acquiring a harvest of information to build a set of rules necessary in order to fully recover the realizable capacity of ancient architecture, in line with that desire to see Rome reborn according to the wishes of the humanists present at the papal court, at the return of that civilization, grafted into Christian culture, and reformed by it, as the architectures worthy of equaling ancient greatness, such as St. Peter’s Basilica and the Vatican Loggias, were proving.” Raphael begins his letter by recalling “the very great things” that the Romans did, and regretting the state in which the traces of Rome’s illustrious past lay at the time: a situation that caused him “great sorrow, seeing almost the corpse of that noble country, which has been queen of the world, so miserably lacerated.” And according to the Urbino, it was not only the barbarians who had wreaked havoc on Rome’s buildings, and with them time and the centuries of neglect and abandonment that Rome had known: the blame for the current state of affairs was also to be laid at the door of his contemporaries, who had been little concerned with protecting the goods of antiquity.

“It seemed that time,” writes Raphael, “as if envious of the glory of mortals, not trusting fully to its own forces alone, agreed with fortune and with the profane and wicked Barbarians, who to the edacious file and venomous bite of that added lempio furore and iron and fire and all those ways that sufficed to ruin it. Wherefore those famous works, which nowadays more than ever would be flourishing and beautiful, were by the wicked rage and cruel impetus of wicked men, nay fair, burned and destroyed.” The buildings thus ruined were little more than skeletons, they were "bones without flesh," to use Raphael’s own expression. And then here is the attack on contemporaries: “But why shall we grieve for the Goths, Vandals, and daltri such perfidious enemies, if those whom as fathers and guardians should have defended these poor relics of Rome, they themselves have long waited to destroy them?” The accusations are addressed to the popes who preceded Leo X (“How many Pontiffs, Most Holy Father, who had the same office that Your Holiness has, but not already the same knowledge, nor the same valor and greatness danimo, nor that clemency which makes you like God: how many, I say, Pontiffs have waited to ruin ancient temples, statues, arches and other glorious buildings!”), and to all those who did not scruple to reuse passages and fragments of ancient monuments as building materials (“How many have entailed that merely to take pozzolan earth foundations were dug, so that in a short time then buildings came to the ground! How much lime has been made of statues and other ancient ornaments! that I would dare say that all this new Rome that is now seen, how great that it is, how beautiful, how ornate with palaces, churches and other buildings that we discover it, all is fabricated of lime and ancient marbles”).

Then follows a list of dilapidated buildings, but soon comes the pars costruens of Raphael’s letter: the fact that the ancient buildings were in ruins did not mean that one could not try to equal and surpass the Romans of old. The pope is thus addressed with the invitation to take care of what remains of ancient times, and defend the monuments from the “malignant” and “ignorant.” “It must not, therefore, Most Holy Father, be among the last thoughts of Your Holiness to take care that what little remains of this ancient mother of Italian glory and greatness, as a testimony to the valor and virtue of those divine spirits, who even sometimes by their memory excite to virtue the spirits who are among us today, should not be extirpated, and spoiled by the malignant and ignorant.” The defense of culture is the basis for everything else: “Just as from the calamity of war comes the destruction and ruin of all disciplines and arts, so from peace and concord comes happiness to peoples, and the laudable idleness by which they can be given work and make us arrive at the culmination of excellence, where by the divine counsel of Your Holiness all hope that we have to reach our century. And this is to be truly the most clement Pastor, indeed the most excellent Father of the whole world”: the pontiff’s task, Raphael writes, is to foster virtue, awaken wits, reward labors, sow peace and concord. It is also in this sense that the defense of antiquity should be read.

|

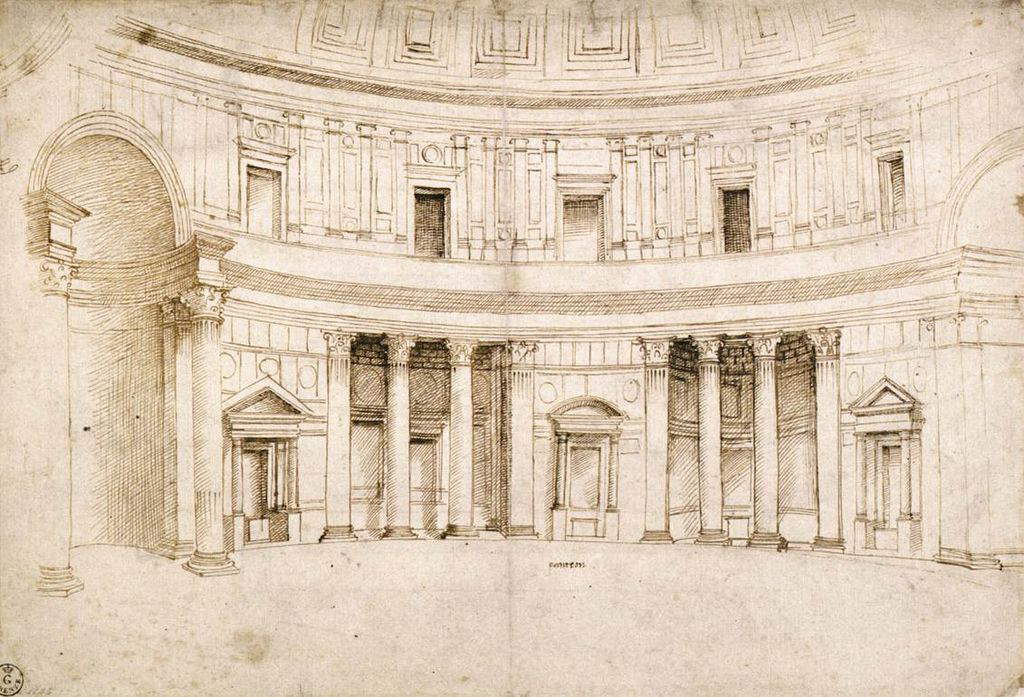

| Raphael, Interior of the Pantheon (c. 1506; pen and ink on paper, 277 x 407 mm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

In the following part, Raphael traces a kind of history of architecture from antiquity to his own time, dividing it into three phases: that of the ancients, that of the “gotti” (an indistinct period from the end of the Roman Empire to the days of Raphael: it is, in essence, our Middle Ages, but artistically the painter does not distinguish the different phases). And according to the mentality of the time, Raphael does not skimp on hierarchies of merit, deeming the buildings of the time of the emperors “the most excellent and made with great art and beautiful manner of architecture.” Moreover, according to the artist, architecture was the last of the arts to know decline: in his view, letters, sculpture and painting had already undergone a kind of involution well before the end of the empire, and as an example Raphael recalls the Arch of Constantine, “the composition of which is beautiful and well made in everything that belongs to architecture, but the sculptures of the same arch are most foolish, without art or bounty whatsoever,” and the same would be true in his opinion of the Baths of Diocletian, where “the sculptures are most clumsy and the relics of painting seen there have nothing to do with those of the time of Trajan and Titus: pure, the architecture is noble and well intended.”

Of course, in Raphael’s classification, the art of the “gotti” is the least valuable (“then that Rome by the Barbarians in everything was ruined and burned,” the artist premised, “it seemed that that fire and miserable ruin burned and ruined, together with the buildings, even the art of building”). It is interesting here to point out how, according to Raphael, art and freedom go hand in hand: indeed, the painter attributes the decline of art to the fact that the fortunes of the Romans had changed, and that the Romans, “subjugated and made servants by the barbarians,” were no longer able to produce quality art because they were no longer free, and that indeed art “without measure, without any grace” had followed the fate of the Romans deprived of their freedom (“it seemed that the men of that time, together with freedom, lost all their wit and art”). The same would have happened in Greece, a land that, although it could boast “the inventors and perfect masters of all the arts,” reduced to subservience found itself producing “a manner of painting, sculpture, and architecture bad and of no value.” And while recognizing some value in the art of the “Germans” (Romanesque art, as described: “li Tedeschi [...] per ornament often placed only some huddled and ill-made figurine for a shelf, to support a beam, and strange animals and figures and clumsy foliage and out of dogni ragione naturale”: nothing to do, according to Raphael, with the Romans who built following the proportions of man and woman), there remained, however, a marked distance from the art of the Romans.

![Raffaello e Baldassarre Castiglione, Lettera a papa Leone X (s.d. [1519], manoscritto cartaceo, 6 carte di 220 x 290 mm circa ciascuna; Mantova, Archivio di Stato)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2020/1363/raffaello-baldassarre-castiglione-lettera-a-leone-x.jpg) |

| Raphael and Baldassarre Castiglione, Letter to Pope Leo X (s.d. [1519], paper manuscript, 6 papers, about 220 x 290 mm each; Mantua, State Archives) |

In the last part of the letter, Raphael explains to Leo X the technique he used to measure ancient buildings: an instrument created by the painter himself, which we can imagine as a kind of sundial installed above a compass divided into eight sections corresponding to the eight winds, in turn divided into thirty-two degrees. Using a moving magnet, the artist would thus take measurements of the buildings, deriving spatial coordinates through the compass. The scaled measurements would then be reported on paper and organized into three parts, “of which the first is the plan, or we want to say dissegno piano, the second is the parete di fori con li suoi ornamenti, the third the parete di dentro con li suoi ornamenti”: Raphael thus prescribed the use of what in modern terms we call plan, elevation and section.

“This portion of the text, although specifically technical,” Terraroli writes, “reveals the commitment and care with which the artist tackles the theme of a philological and precise restitution of ancient buildings, reconstituting, albeit virtually, the parts that have been destroyed in the course of time: only in this way can the torn limbs of theUrbe resurrect [....] and only thus can the design and technical sense of ancient architecture be reconstituted conceptually, not through a pictorial reconstruction of a perspective and evocative type, but through a graphic and philological restitution of architectural measurements.” As anticipated, Raphael’s untimely death crushed his intentions, and the project to create a complete mapping of the buildings of ancient Rome never found its own actualization. Yet, despite the fact that the letter had no practical consequences, it is a text that not only represents one of the most shining evidences of Renaissance culture, but also has a theoretical bearing of inestimable value, one that spans the centuries, one that is considered to be at the origin of the modern concept of protection, and one that some (such as Luisa Onesta Tamassia, director of the State Archives of Mantua) also see as a premonition of Article 9 of the Italian Constitution (“The Republic promotes the development of culture and scientific and technical research. It protects the landscape and the historical and artistic heritage of the Nation.”). Most importantly, it is a text that states that the protection of ancient heritage must not be an end in itself, but must provide examples to give a way to equalize and surpass what previous generations have done. Because keeping the memory of the past alive helps us live better in the present.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.