The following article is an excerpt from the critical text in the catalog of the exhibition Preraphaelites. Modern Renaissance, directed by Gianfranco Brunelli and curated by Elizabeth Prettejohn , Peter Trippi, Cristina Acidini and Francesco Parisi with advice from Tim Barringer, Stephen Calloway, Charlotte Gere, Véronique Gerard Powell and Paola Refice, running through June 30, 2024 at the Museo Civico San Domenico in Forlì.

In 1899, fifty-one years after founding the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with six other young men, William Michael Rossetti recalled, “The temper of those young men, after a few years of present academic training, was the temper of rebels: They wanted revolt, and they made a revolution,” Thinking back to the spring of 1849, when the Brotherhood’s paintings were first exhibited in public, he described “a clique of restless and ambitious young spirits, determined to make a fresh start on their own and clear away certain sluggish respectability.” Every generation produces dissatisfied young people, and the history of Western art is punctuated by a series of revolts, some with more lasting effects than others. However, the Brotherhood’s rebellion was not only about aesthetics. They admired historian Thomas Carlyle, who in his influential work Past and Present (1843) observed that the English nation needed to “learn to understand the meaning of its strange, new today.”England, particularly London, where the Pre-Raphaelites resided, was the center of the largest global empire that had ever existed, perfectly connected to the world but grappling with profound internal changes: the rising bourgeoisie prospered while workers lived in extreme poverty, often in crowded cities and industrial centers that expanded at the expense of nature. Given this unstable context, Tim Barringer and Jason Rosenfeld have identified the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood as an avant-garde movement, “overthrowing current artistic orthodoxies and replacing them with new critical practices, often directly confronting the contemporary world”; it was no coincidence that it was formed in that same year, 1848, in which revolutions broke out in continental Europe and their less violent English variant, namely the Chartist movement, called for a “people’s charter” guaranteeing suffrage and secret ballot for all men twenty-one and over. On April 10, 1848, two students from the Royal Academy Schools, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, participated in the great Chartist demonstration in London, and in the fall they conveyed its reform spirit to the first meeting of the Brotherhood, which was held at Millais’s family home in central London.

Ranging in age from nineteen to twenty-three, the seven founders were not just restless young men who wanted to scandalize those older than them; as Elizabeth Prettejohn writes, “the young Pre-Raphaelites’ revolt against the Victorian art establishment is unique in the history of modern art because it was an attack from above.” For them, “the establishment, represented by established Royal Academy figures such as [Edwin] Landseer and [Charles Robert] Leslie, meant commercial success achieved through the depiction of pleasing and anecdotal subjects suited to the domestic environment of the affluent bourgeoisie. The Pre-Raphaelites expressed an implicit criticism of the older artists by adopting more serious and elevated subjects than Landseer’s dogs and amiable scenes from Leslie’s literature.” From the outset, then, the Brethren chose subjects that directly dealt with moral, religious, social and political themes of pressing interest to them but unfamiliar or disconcerting to most of the public, adopting compositions and techniques that were both historically grounded and experimental. Their innovations become clearer from a comparison with Leslie Queen’s well-crafted painting Katherine and Patience, which depicts a scene from Shakespeare’s play Henry VIII. With its restrained palette and striking chiaroscuro, the work exemplifies the conventional narrative art appreciated by middle-class buyers at the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition, where it was displayed; and indeed it was bought by John Sheepshanks, a Leeds industrialist who fifteen years later donated his collection of such paintings to the nation. Shakespeare was one of the Pre-Raphaelites’ heroes, and we will see later how much bolder their interpretation of his plots was.

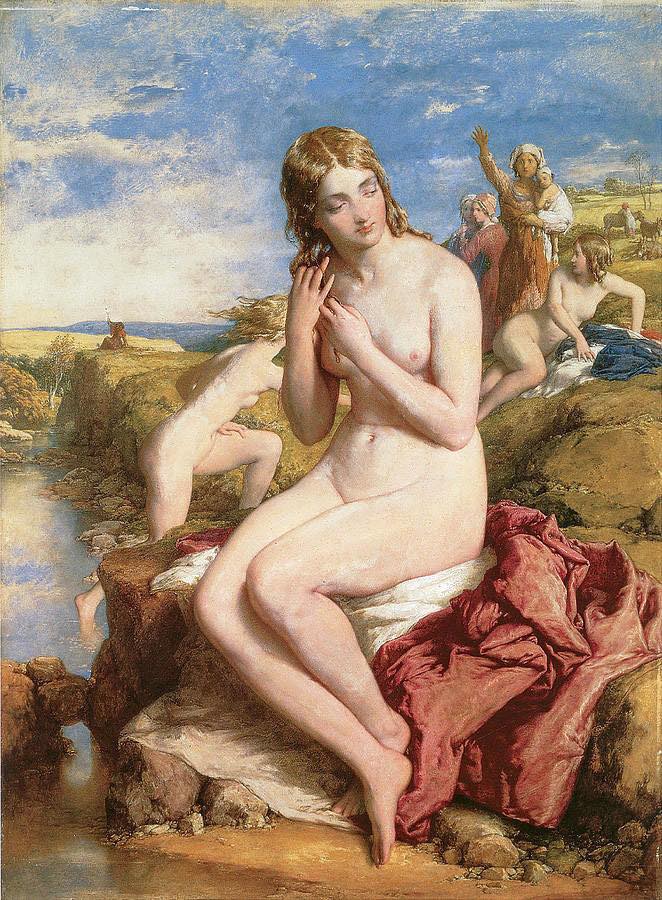

William Michael Rossetti’s aforementioned 1899 recollections should be read considering that they were written decades after the event. The same is true of Holman Hunt’s memoirs, which were published in a series of articles in the 1880s and as a volume in 1905; however, there is no reason to doubt his claim when he writes that in the 1940s he admired the technical skill of Leslie and other successful academics, such as William Etty, William Mulready and Augustus Leopold Egg. In any case, for Hunt almost all the artists exhibiting at the Royal Academy were “trite and affected; in my eyes, their most frequent fault was that they replaced beauty with vacuous loveliness [...]. The painted wax statues playing the part of human beings irritated me, and often the banal conventionality turned me away from masters whose merits I otherwise appreciated.” As for the academics’ technique, William Michael Rossetti writes that the Brethren “detested those forms of execution which are merely polished and graceful, and those which, aspiring to mastery, are but hasty and approximate, or, as they said, ’sloppy.’”

The seven young men present at that first meeting in the fall of 1848 came from various middle-class backgrounds and had very different artistic abilities. Millais, Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti were studying at the Royal Academy Schools; Rossetti attended only occasionally and struggled with execution, while Millais was a precocious talent, extraordinarily admitted at the age of eleven, and thus was ahead of his friends. These three prominent figures were joined by the sculptor Thomas Woolner, two less talented painters, James Collinson and Frederic George Stephens, and Gabriel’s younger brother, William Michael; later the latter two turned to art criticism and became the Brotherhood’s principal chroniclers. Given the young age of its members, it is not surprising that the group’s meetings were very lively, even goliardic, nor that in the first two years their collaborations were close and varied. Hunt recalls that it was Gabriel who proposed forming but “confraternity,” having inherited from his Italian revolutionary father a taste for intrigue; this makes it all the more surprising that they produced neither a written manifesto nor a group portrait, but only drawings in which they portrayed each other, conveying their youthful ardor. [...]

Instead of the idealization and other conventions pursued in the classrooms and galleries of the Academy, the Brethren admired, as Hunt recalls, “the frankly expressive naïve features and spontaneous grace” characteristic of fifteenth-century art, “so vigorous and innovative,” which flourished before the rules of perspective were established. As Elizabeth Prettejohn has observed, at that time most English artists regarded Italian (and Flammingian) paintings of the early fifteenth century as only an exploratory stage on the path to the more sophisticated art of the so-called High Renaissance. As the seven friends were planning their rebellion, Gabriel proposed the designation “early Christian,” a term he had learned from his teacher Ford Madox Brown, a kindred spirit who had worked in Italy but never formally joined the Brotherhood. Instead, Hunt suggested “Pre-Raphaelites”; he later recalled that he and Millais admired Raphael’s cartoons for the Sistine Chapel tapestries and the St. Catherine of Alexandria, while they felt that the Transfiguration altarpiece (completed by help and known to the two young Englishmen through an engraving), with “its grandiose disregard for the simplicity of truth, the pompous attitudes of the Apostles and the unspiritual pose of the Redeemer,” marked a “decisive stage in the decadence of Italian art.” When the two expressed these remarks to some fellow students at the Academy, those replied, “But then you are Pre-Raphaelites.” Millais and Hunt “agreed, laughing, that that designation had to be accepted,” and so it was eventually joined with “Confraternity.”

In his memoirs, Hunt then argued that “the traditions which have come through the Bolognese Academy to the present day, and which were laid down as the foundation of all the later schools and upheld by Le Brun, Du Fresnoy, Raphael Mengs, and Sir Joshua Reynolds, have exerted a lethal influence, tending to stifle the breath of drawing.” Pieter Paul Rubens could have added to this problematic lineage: in his copy of Anna Jameson’s widely circulated book Sacred and Legendary Art (1848), at each occurrence of the Flemish master’s name Gabriel noted in the margin, “Spit here.” Although undeniably skilled, to him Rubens represented everything that was excessive and vulgar about the academic system. Thus, the Brethren rejected the curriculum established by Reynolds, with its plaster casts to be copied, nude models, and post-sixteenth-century color palette. However, William Michael warns, “It would be a mistake to believe that because they called themselves Pre-Raphaelites, they did not seriously appreciate the production of Raphael”; more accurately, “they detested what that had been accomplished by the insignificant epigones of Raphael, and they were determined to discover by personal study and practice what their different abilities and potentialities were, without being bound by rules and wigwams based on the work of Raphael or anyone else. They would have no other teachers than the capacities of their own mind and hand, and the direct study of nature [...]. This had to be profound, and representation (at least in the initial stages of self-discipline and work) exact to the highest degree.”

In trying to improve “the abilities of their minds and hands,” drawing together-and commenting on albums of drawings-proved crucial to the Brothers’ team spirit. Many of them had been members of the Cyclographic Society, a drawing circle founded in early 1848. At their first meeting, the Brothers studied a volume of Carlo Lasinio’s prints from the frescoes in the Camposanto in Pisa, attributed to artists such as Benozzo Gozzoli, Orcagna and Giotto. Traces of Lasinio can be found in their graphic style, which is strongly linear, devoid of shading and deliberately clumsy." They adopted this method not so much to reproduce ancient art as to unlearn the conventions of grace and accuracy of modeling imposed by the academic system. The consistency of their early drawings was not reflected in the paintings on display, and this inconsistency could already be detected in the “list of immortals” compiled by Hunt and Gabriel in the summer of 1848: such a list of more than fifty “heroes” ranked according to five levels (where only Jesus Christ was assigned four stars), although extravagant and contradictory, gives us an idea of the tastes of these rather cosmopolitan young people. It includes not only artists but also as many poets, including Dante, Boccaccio, Shakespeare, Keats and Tennyson; from the 15th century are Ghiberti, Beato Angelico and Bellini, but there is no shortage of High Renaissance masters such as Raphael, Leonardo, “Michael Angelo,” “Giorgioni,” Titian and Tintoretto. The list included Early Gothic Architects (Early Gothic Architects), but it could have mentioned other obvious references such as Van Eyck, Dürer, and the anonymous authors of illuminated manuscripts, miniatures, and medieval stained glass, if not also modern sources of inspiration such as photography and Nazarene painters still active in Rome. [...]

In May 1849 the Brethren gave the English art world a first taste of their creativity: the Royal Academy’s jury admitted Hunt’s Rienzi and Millais’s Isabella to its prestigious summer exhibition. In addition to these two paintings, displayed in the same room as Collinson’s painting, Italian Image-Boys at a Roadside Alehouse, whose style was reminiscent of Leslie’s, Gabriel’s The Girlhood of Mary Virgin was presented at the nearby Free Exhibition (so called because it had no jury). All four artists had initialed their works with the initials PRB. (Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood), as a parody of the privileged marks of royal academicians, RA. (Royal Academician) and A.R.A. (Associate of the Royal Academy). In 1849 and subsequent years, visitors to exhibitions could not ignore what art historian John Christian called the “spring freshness” of Pre-Raphaelite paintings. Even today their luminosity and emotional force make the heart beat faster, and that year many critics praised the artists for their ambition and seriousness. Some observers had some reservations about the sharp lines, the deliberate archaisms, the eerie uniformity of light, and the minuteness of detail across the painted surface (the latter derived more from the Flemish than the Italians), but they did not grasp the insolence of the group’s acronym, which therefore did not cause an uproar. [...]

Over the years the Brethren wrote poems, essays, reviews, catalog entries and their own pamphlets, and endowed their paintings and frames with inscriptions. On May 15, 1849, shortly after the Brotherhood’s first works were presented to the public, William Michael began keeping a journal of the group, with daily entries until April 8, 1850, after which date they became less regular, ceasing altogether on January 29, 1853. William Michael also became the group’s secretary (the only formal position within the Brotherhood) and in late 1849 began editing its journal, “The Germ: Thoughts toward Nature in Poetry, Literature, and Art.” Launched in January 1850, it published poems, short stories, prose essays, and engravings from drawings that the Brethren executed specially. With a typeface that William recalled as “aggressively gothic,” “The Germ” was to run monthly, to sow the seeds of the cultural reforms pursued by the Brethren and their circle. In the end, because sales were poor, only four issues (January, February, March, and May 1850) came out, which nevertheless usefully shed light, now as then, on how the Pre-Raphaelites conceived their revolutionary work. [...]

The relatively quiet reception accorded to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1849 did not last. William Michael recalls, “Established painters and critics routinely [by 1850] had by this time realized that the young artists had determined personal intentions and a concerted plan of action.” On May 4, 1850, the widely circulated magazine “Ilustrated London News” revealed the meaning of the acronym “P.R.B.,” which is ironic considering that the Brethren had decided not to initial the paintings they would present that summer. As these were exhibited at the Royal Academy, the greatest scorn fell on Hunt’s A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of the Druids and, especially, on Millais’ Christ in the House of His Parents. Most critics, if they found the former puzzling, were vigorously indignant about the latter, which followed a path so different from the idealized rendering of the same subject successfully presented to the Academy three years earlier by John Rogers Herbert in Our Saviour Subject to His Parents at Nazareth (The Youth of Our Lord). Rich in typological symbolism, realistic figures without embellishments, and powerful empathy for the poverty in which the historical Holy Family lived, Millais’ painting still represents a provocation to some. It attracted harsh reviews, in one of which we read, “In all [Italian primitive painters] the absence of structural knowledge has never produced total deformity. The disgusting inconveniences that go with unwashed bodies were not presented with a repulsive reality; and the flesh, with its filthiness, was not exploited as an artificial means of religious sentiment in revelations of bad taste.”

Particularly infamous was a scathing critique written by Charles Dickens who, although his works are populated by imperfect people taken from real life, could not understand why a gifted artist like Millais should mix realism and symbolism, moreover denying art’s historical progress toward idealized beauty. The ferocity of the criticism strained the Brotherhood so severely that in the same year James Collinson, who had converted to Catholicism, resigned. On display at the nearby National Institution (the Free Institution’s new name) was Gabriel’s Ecce Ancilla Domini, of which one critic wrote, “An obtuse imitation of mere technicalities of ancient art - gilded glories, extravagant scribbles on the frame and other puerile absurdities - is all its boast.” Effectively the frame bore a Latin inscription, and the Latin title itself irritated some of the public, already apprehensive about the much-discussed restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in England, which eventually took place in September of that year. Indeed, the canvases or frames of many of the Pre-Raphaelites’ paintings (including The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and Rienzi) were centered, with a form that evoked historic (i.e., Catholic) altarpieces, but the Brethren, while devout, had very different approaches to the Christian faith. Most English artists of this period shunned religious iconography, fearing its pitfalls (and poor sales); Christ in the House of His Parents and Ecce Ancilla Domini thus represent their authors’ revolutionary attempt to bring it back into vogue in Britain without falling back into Catholic mores, but rather emphasizing the emotionally intense and universally human themes offered by the Bible.

Through the stark effect and unusual composition, in The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and Ecce Ancilla Domini Gabriel convincingly reminded Protestant audiences of the universal purity of the Virgin, infusing the latter painting with a psychological energy that enhances the miraculous, supernatural aspect of the message brought by the archangel. On display at the National Institution’s 1850 exhibition next to Ecce Ancilla Domini was Twelfth Night, a scene from Shakespeare’s famous play painted by Walter Deverell, who that same year had applied to join the Brotherhood but was never formally elected. Throughout this period Shakespeare was revered by virtually every British citizen, but the Pre-Raphaelites harbored a particular enthusiasm for the Bard and painted several episodes that extolled the moral and emotional depth of his work, rather than its entertaining character (Deverell himself was an actor, and as an artist he specialized in Shakespearean subjects). Playfully evoking a theatrical set, with its flattened perspective bordered at the top by the archway, Deverell’s painting makes its own the Pre-Raphaelite rejection of symmetrical composition. Although the eye is drawn first and foremost to the figures in the center (Deverell as the long-haired Orsino, Gabriel as the jester Feste, and Elizabeth Siddal as Viola), it is not clear where to look next. “The Times” wrote that Deverell was attempting “to turn the flat medieval style into a more humane tale, but his faces are ordinary, and though he works with care, his mannerism is more evident than his genius.” Whether its members wanted it or not, the uproar of the 1850s gave fame to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, so much so that Queen Victoria had Christ in the House of His Parents brought to the palace to see what all the fuss was about. Notoriety had not yet waned by the spring of 1851, when their most recent paintings were exhibited in London, including Millais’s The Return of the Dove to the Ark (from the Old Testament) and Mariana (from Tennyson) and Hunt’s Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus (from Shakespeare’s The Two Gentlemen of Verona). Millais’s The Woodman’s Daughter , exhibited at the Academy in 1851, received more favorable reviews with its verdant English landscape executed from life, more vivid in its naturalism and more convincing in perspective than any other Pre-Raphaelite painting up to that time. Inspired by a poem by Coventry Patmore, a poet who supported the Brotherhood, the painting depicts a rich child offering a handful of strawberries to Maud, the daughter of the woodsman intent on cutting down a tree in the background. Their friendship will result in an illegitimate child, whom Maud will drown before going mad, because a marriage between people of such different classes is impossible; the felled tree represents Maud herself. As in Isabella, Millais presents these social divisions as immoral and inhuman; here the contemporary setting makes the critique more explicit, echoing the sympathy for workers expressed in other contexts by Carlyle, Ruskin, and Ford Madox Brown. [...]

In May 1851, shortly after the opening of the London exhibitions, Ruskin sent two eloquent letters to The Times, England’s leading newspaper. Although not entirely flattering, his words changed the public perception of the Pre-Raphaelite project: “They intend to return to the past in this one point: they wish to draw, as far as is within their ability, either what they see, or what they presume may have been the actual facts of the scene they wish to represent, independently of all conventional rules of painting; and they have chosen their unhappy though not inaccurate name precisely because that is what all artists did before the time of Raphael, while after the time of Raphael they no longer did so, but sought to paint beautiful pictures instead of representing factual nudes; the consequence of which has been that, from the time of Raphael to the present day, historical art is in an admitted decadence.”

In 1847 Hunt had read Ruskin’s Modern Painters, admiring his call to “turn to nature in total simplicity of heart [...] rejecting nothing, choosing nothing, and despising nothing; believing all things to be good and right, and always being pleased with the truth.” By equating “bare facts” with nature, in his letter to the Times Ruskin deftly shifted the focus from the primitivism of the Pre-Raphaelites to their naturalism and their dedication to direct observation (instead of idealization), reminding observers that past and present were not incompatible. Rather, he asserted that the Pre-Raphaelites “do not intend to renounce any advantage which the knowledge or inventions of the present may offer to their art.” Ruskin’s support opened many eyes and doors to the Brotherhood; yet, as early as December 1850 William Michael took note of its gradual dissolution. This is a recurring development in the history of the avant-garde, and it was clear that the fellowship had outlived its usefulness for Millais, Hunt and Rossetti, who were rapidly evolving in different directions. In the short time they spent together they left a very deep imprint, revealing new aesthetic possibilities whose echoes still resonate to this day. In August 1850, a critic had commented in the “Guardian”: “Hitherto English artists have worked each on his own, practically without a common purpose or a definite intellectual object pursued with constancy [...] Here, at last, we have a school [...] Its purpose [...] is high and pure. No one can walk our streets without noticing how corrupt and material our tastes are now [...]. The success of their attempt would be a national blessing.” The Brotherhood began a revolt, a true “national blessing,” which took root and still continues.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.