Pisanello's animals according to Adolfo Venturi, between Gothic ties and Renaissance impulses

It is known to most that Pisanello, one of the major painters of the northern Italian art scene during the 15th century, had a considerable interest in the depiction of animals: we find them in several of his works, and they are the protagonists of a large number of studies and drawings. Any contribution dedicated to Pisanello never neglects to analyze this particular aspect of his production. And an analysis of thenaturalistic investigation in the work of Antonio di Puccio Pisano (this is his real name) is also conducted in what is considered one of the first reasoned studies on the artist: it is the preface to the critical edition of Vasari’s Lives of Gentile da Fabriano and Pisanello, edited by Adolfo Venturi and published by the Florentine publisher Sansoni in 1896.

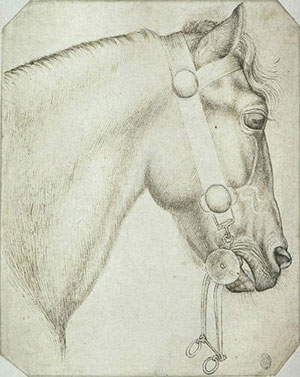

|

| Head of a Horse (probable study for the fresco of Saint George; c. 1433-1438 or c. 1450; Paris, Louvre, Cabinet des Dessins) |

We start with an assumption: that Pisanello is a keen observer of reality, who for his art takes his cue, according to Venturi, from the world around him, “and more from the earth than from man, more from the life of animals than from himself or his fellow men.” Venturi’s words that the artist was more interested in man than in animals would seem to be confirmed in his corpus of drawings, most of which are preserved in the Cabinet des Dessins of the Louvre: the human presence, in these drawings, is abundantly outclassed by the animal one. The spread of the late Gothic taste, with its fairy-tale and courtly atmospheres, required artists to be able to paint the animals that were often the protagonists of the narratives: so, of course, Pisanello is not the only artist of the period who had a strong interest in the world of nature. “Dogs of every species, horses and mules, monkeys, rare animals, common animals, birds seen flying through the valleys and in the Marchesan courts trained for hunting”: these are the animals that are part of Pisanello’s bestiary.

But evidently there must have been more to Pisanello than his contemporaries, because Venturi is convinced that the artist sought “preferably subjects with animals,” and in several of his paintings we see him as he “unleashes dogs, trots horses, and flies the birds he saw in the circumpadane plains of Ferrara, in the lakes and marshes formed by the Mincio around Mantua.” Pisanello’s, in essence, was probably a strong passion. To make a complete examination of Pisanello’s paintings in which animals appear would be a rather lengthy operation. But suffice it to mention a few famous examples, such as the celebrated Madonna of the Quail, preserved in the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona, in which, in addition to the bird that gives the painting its name, two goldfinches appear, one resting on a branch and the other spreading its wings to take flight: They symbolize the Passion of Christ, since the beast feeds on thistle seeds, the plant from which, according to tradition, Christ’s crown of thorns was made, and the red stain the goldfinch has on its head is a symbolic reference to Christ’s blood shed on the cross. We could mention the precise anatomies of the horses in the famous fresco with St. George and the princess in the church of St. Anastasia, also in Verona, where dogs of different breeds, a goat, and a dragon appear as well, around which the artist’s imagination has concentrated a series of human and animal remains devoured by the monster. And, of course, one cannot fail to give a brief mention to the Vision of St. Eustace from the National Gallery in London, a work in which the protagonist is depicted in the company of “many little birds” that “flutter around a patch of trees,” deer that “go to water in the rivulets of the bottom,” a lake with ducks, swans, pelicans, and storks, and even a bear that wanders among the ravines.

|

| The quail and the two goldfinches, details from Madonna of the Quail (c. 1420; Verona, Museo di Castelvecchio) |

|

| Some animals in the fresco of Saint George (c. 1433-1438 or c. 1450; Verona, Sant’Anastasia) |

|

| Dogs in the Vision of Saint Eustace (c. 1438-1442; London, National Gallery) |

In all the above paintings there is still a lack of a conception of space that could be called Renaissance: this is one of the reasons why an artist straddling two epochs like Pisanello is, by preference, labeled “late Gothic.” There is no doubt, however, that there are pro-Renaissance impulses in his art: and we are not referring only to his medallistics (which we can, however, already consider fully Renaissance), but also, clearly, to his interests in nature. Adolfo Venturi holds the merit of having been among the first to identify these exceptionally modern components in Pisanello’s art. The study of nature, the interest in animals, the use of having the saints transported into the everyday life of the courts of the 15th century and made to “live to hunt like gentlemen, dress the fashions of knights, torneare innanzi a damsel”-all characteristics that, according to Venturi, should lead one to consider Pisanello an outstanding figure, the author of a sort of first rupture between the late Gothic past of northern Italy and Renaissance modernity: With Pisanello, says Venturi, “there ceased in the northern art of Italy the Gothic form, which had been grafted with difficulty onto the Romanesque trunk, and all the ancient traditions no longer corresponding to nature and life, all the wise conventional formulas of the past, fell.”

|

| Hunting Dog (probable study for St. George fresco; c. 1433-1438 or c. 1450; Paris, Louvre, Cabinet des Dessins) |

It is true that the high degree of precision with which Pisanello depicted his animals, unmatched for the historical period in which he lived, is not enough to define his interest in animals as Renaissance. Nor does it help to make it innovative that the animals were studied from life-a practice also common to other artists of the time, although Pisanello practiced it much more extensively than his contemporaries, who often copied from pre-existing models. Still keeping Pisanello’s interest in animals tied, to a large extent, to the past is the fact that this interest was never systematic, and the painter’s studies of nature were never organized according to pre-established criteria. Bringing more clarity to this point has been provided by art historian Tiziana Franco, among others, with an essay on the painter’s workshop dated 1998, according to whom Pisanello’s drawings would not completely sever ties with the late Gothic milieu to which the painter belonged: the vast majority of Pisanello’s drawings that have been preserved would in fact respond to a very specific purpose. In the workshops of the time, the practice of drawing was widespread: through drawing, historical memory was preserved (by copying older works, for example), or a repertoire of motifs fundamental to the painter’s activity was being created, and from these repertoires he derived the figures that would later populate the paintings. With his drawings, with his studies of nature, Pisanello was drawing motifs from reality and then bringing them into the finished works. Or even simply to study poses, connotations, expressions: in fact, there are drawings that did not constitute preparatory studies for paintings or frescoes, but were nevertheless necessary for this peculiar activity that Pisanello conducted.

Of course: it is difficult to give an account in a single article of a vast subject, which would probably require an entire book. We can limit ourselves to reflecting on the fact that with Pisanello we may not yet be able to speak of Renaissance, because the artist’s attitude can still be considered that proper of the late Gothic world, but there is no doubt that with him a discontinuity with the past was created, not only because his precision in the representations of nature and animals reached very high levels for the time, but also because his curiositas, noted by several scholars, was a new fact: it can be considered an anticipation of what would come after him. And Adolfo Venturi must be credited with having been among the first scholars to identify with great precision the importance of this great artist, whose name is today included among the prominent ones in our art history.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.