Pisa's Putti Fountain, from demolition to Lupin III and Instagram

La mode se démode, le style jamais!, so goes a famous adage, attributed to Coco Chanel, but which seems tailor-made to adhere to certain customs, very recurrent in the world of art; today we borrow it to describe an exemplary affair, that of the Fountain of the Putti in the Piazza del Duomo in Pisa, long despised by public and critics, and now enjoying unexpected popularity.

That taste mutates, and that this constant change affects not only the cutting of coats but also the alternating fortunes of entire artistic movements and currents, is now well known; rarely, however, do we pause to reflect on the consequences of this incessant fluctuation on our urban landscape. Almost in every era we have unceremoniously disposed of works whose taste was perceived as outdated, inadequate, outmoded, if not explicitly incorrect, wrong, bad, and we have proceeded to the adaptation, or more often the removal, demolition and replacement of artistic artifacts or entire architectures without much hesitation.

Then when larte finds itself going through turbulent epochs, with social earthquakes and sudden regime changes woe to the vanquished, even those in marble! Pagan gods and ancient philosophers? Perfect for firing in Roman lime kilns (apparently those made of Greek marble gave the best quality lime). Cumbersome noble coats of arms on altars and portals? Off with the revolutionary chisel ready to cassette them, in accordance with customs still in vogue, which see Soviet monuments disappearing, statues of Unionist generals in the U.S., all the way to ISIS vandalism or discussion of the removal of some surviving DUX.

At the end of the 18th century, the collapse of theancienrégime, and the disappearance of white wigs and buckles on shoes, is accompanied by a change in taste, overtly political, which on the one hand promotes the emerging neoclassicism and on the other condemns without appeal the art of the 18th century. It is not only the openly anti-classical tendencies of the first half of the century, soon labeled with the derogatory termRococo, that suffer the consequences, but also the extended and important phenomenon of eighteenth-century classicism, condemned to a damnatio memoriae sealed by the grave words of Count Leopoldo Cicognara: Larchitecture and sculpture were still jammed in bad habits, and no works were seen that announced in any way their forthcoming resurgence (1824).

The Fountain of the Putti, in Pisa’s cathedral square, had the misfortune to make its debut (in 1765) right on the threshold of a period of great change; the monumental sculptural group, with the three colossal putti holding the arms of the primatial and the city, is the child of an exquisitely eighteenth-century figurative culture, quite unprejudiced, fond of asymmetry, ultimately anti-classical, brought to the extreme consequence of a composition in perpetual motion and exquisitely decorative. The same author of the group, Giovanni Antonio Cybei, just three years later, would express himself with a completely different poetics, archeologizing and courtly, in the funeral monument of Francesco Algarotti, a few dozen meters away in the Monumental Cemetery.

|

| Giovanni Antonio Cybei and Giuseppe Vaccà , Fountain of the Putti (1746-1765; marble; Pisa, Piazza del Duomo) |

A fountain existed in the square as early as 1659, without any special ornamentation, but it is due to the zeal of Opera worker Francesco Quarantotti, in office since 1729, that the present structure was built in such a strategic location, in the corner of the paved street that goes to the church. The first phase of the work, completed in 1746, included the erection of a base and the actual fountain, the realization of which was entrusted to Giuseppe Vaccà from Carrara; the good level of execution does not, however, mask the very dated repertoire, with references to Mannerism and a neo-sixteenth-century tendency of typically Florentine taste. For the upper part it was decided to complete the work with the creation of a more ambitious marble group, and this time it was the worker Anton Francesco Maria Quarantotti, who succeeded his father in the position, who made arrangements with the usual Vaccà for the supply of the sculpture (1763). The task, however, was beyond the means of the Carrarese or his workshop, and he had to settle for the role of contractor, agreeing to work on a design prepared by Giovanni Battista Tempesti, and having no choice but to entrust a highly experienced artist, Giovanni Antonio Cybei, with the plastic translation of it and its realization in marble.

Limpostazione spavalda dellopera, inaugurated in 1765, is thus the result of an artistic dialogue between painter (the Tempesti author of an early, lost drawing) and sculptor (the Cybei, author of the model preserved in the Primaziale, with substantial changes from the drawing, and of the marble); its swirling, continuous and animated rhythm, without a privileged point of view, the entirely anthropomorphic architecture, the gigantism of the figures, must have somewhat disoriented the viewer, and despite the initial appreciation, criticism was not long in coming. The first written judgment, which has come down to us, is from 1767, when Filippo DAngelo, author of a handwritten Memoir of the Duomo, labels its author as a very bad statuary.

|

| Giovanni Antonio Cybei and Giuseppe Vaccà , Fountain of the Putti, front view. Ph. Credit Luca Aless. |

|

| Giovanni Antonio Cybei and Giuseppe Vaccà , Fountain of the Putti, rear view. Ph. Credit Jordi Ferrer. |

|

| The model of the fountain |

A few years later (1787-1793) came out one of those works that Schlosser catalogued in La Letteratura dei Ciceroni, tour guides, admittedly erudite, but held in consideration of primary sources until recent times: Pisa Illustrata nelle Arti del Disegno, by Alessandro Da Morrona. In the years of Canova and the French Revolution one could hardly conceive of a positive judgment on Cybei’s putti, and Da Morrona, elegantly lapidary, treated the sculptural group with the most complete indifference: left the fountain diricontro, devoid of merit, if the material, and the work in the base are excepted . At most we save the beautiful marble in short, or the work in the base, the fountain proper, executed by Carrara workers a few years earlier.

How many visitors will have strolled through the Piazza dei Miracoli with this pamphlet in hand, turning a blaming glance toward the poor, cyclopean, half-naked marble children? Rarely, however, is a work of art left in the square that is the vituperation of the people, and there is hardly a shortage of diligent citizens, champions of public decorum, who are not ready to pass to the restorative action.

The first to take the initiative was a certain Girolamo Marconi, a Pisan sculptor who has gone down in history for being the only one, among those commissioned to make the statues of the Illustrious Men destined for the Uffizi, whose work was withdrawn after several rejected sketches; the idea was to replace the group and fountain with a beautiful statue of St. Ranieri, and a sober base with the city’s coat of arms. The sketch was submitted in 1842, and the project received approval and appreciation, but without translating into anything concrete; perhaps the cost of dismantling a work of this size had not been well calculated, who knows.

A couple of decades later, in the climate of enthusiasm that followed national unification, in the years of the easy pickaxe of capital Florence, the Association for the Embellishments of the Piazza del Duomo arose in Pisa, which among its various interventions included, inexorably, the Removal of the group of the three Putti, judged to be a work of little value, and its replacement with the statue of the good Buscheto, architect of the Duomo. The noble intent of re-establishing the neo-medieval verbiage so much in vogue at the time, led to no result this time either, and for a new attempt to take down the group one would have to wait for the arrival of the new Archbishop, Pietro Maffi from Lombardy, who arrived in the Pisan archdiocese in 1905; but the new century had begun, and the times were destined to change. The intention was to erect a monument to Galileo Galilei, an idea admittedly quite curious for a man of the cloth, but not for Maffi, a passionate astronomer, president of the Vatican Observatory, and already the author of a volume of Popular Astronomy. To get around the tedious issue of high costs, he proposed the removal of the sculptural group alone, opting to reuse the fountain below. The project, made public in 1906, was overwhelmed by criticism, and for the first time some timid voices were also raised in defense of the Three Puttos, as a now-historicized element; Maffi, in the meantime having become cardinal, returned to the attack a second time in 1922, perhaps hoping for support from the regime (he was, after all, the author of a famous pro-nationalist speech, published with an illuminating title: For the Triumph of Our Arms) and falling back on the ex-novo creation of a monument to Galilei, symmetrical to the spring and like it, at the beginning of a street and introduction to the meadow. Maffi seemed very decisive this time, and invited the Genoese sculptor Antonio Bozzano, a teacher in the art school of Pietrasanta, to make a sketch for the work, drawing on himself the suspicion that they wanted to first make the work in marble, and then propose its placement on the fountain to avoid the expense of a new base. What saved the Fountain of the Putti for good was the non-election to the papal throne of Cardinal Maffi himself, who was among the papabili at the 1922 Council that saw Archbishop Achille Ratti of Milan (Pius XI) ascend to the papal throne. With a project backed by a pontiff, it would be the end for the Cybei group, for which a century of pitfalls was coming to a close; the Three Putti had finally earned their place among the monuments of the square.

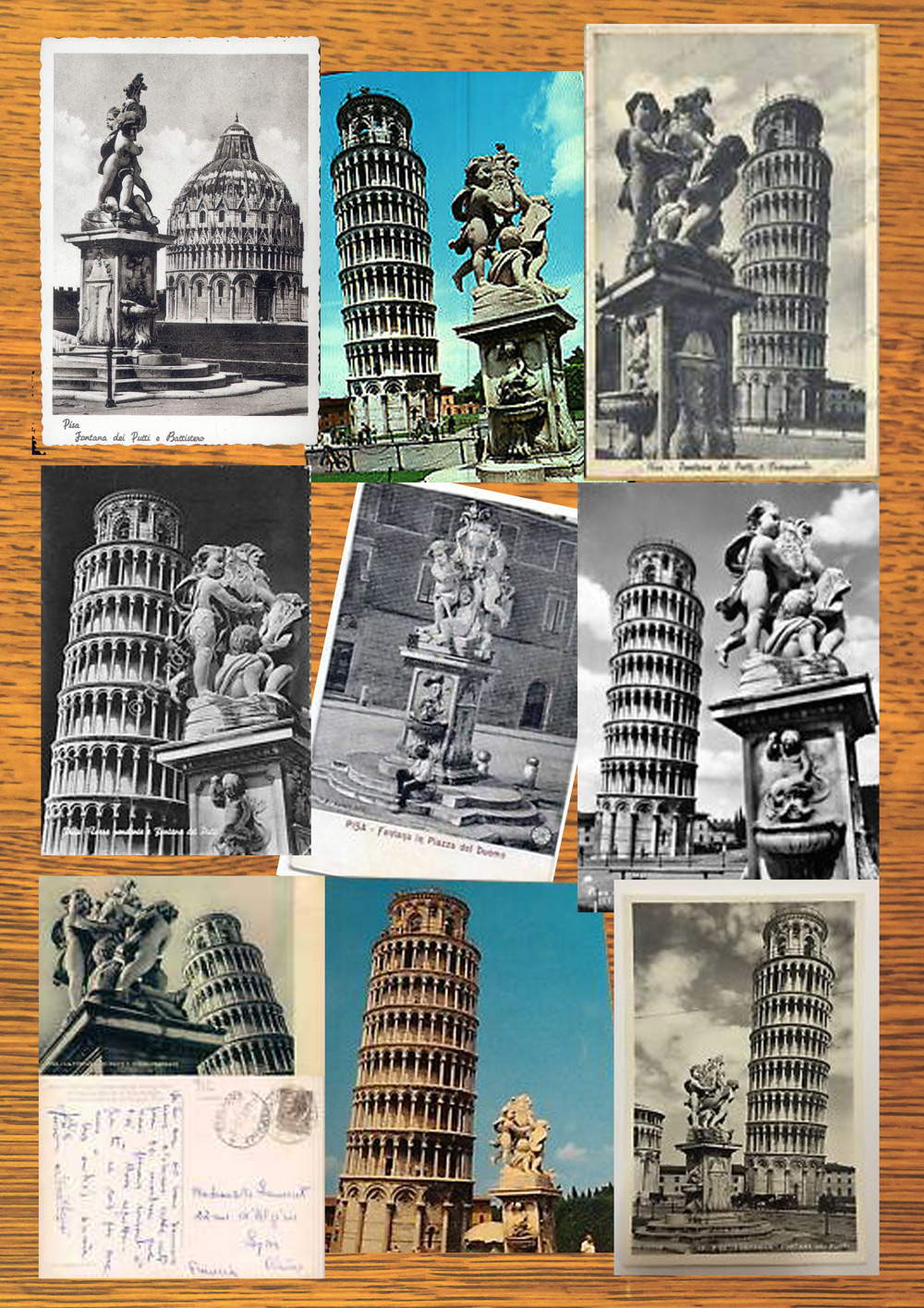

The era of reappraisal began, for a work hitherto so opposed; a reappraisal that would not arise from academic considerations or those of critics, but would have a spontaneous, natural and, why not, popular character. The first vehicle of this new appreciation was the postcard, the revolutionary new format that depopulated in Italy from the end of the nineteenth century for about a century; the more classic view of the Piazza dei Miracoli, taken allincirca from the Porta Nuova, which encloses Baptistery Cathedral and Tower excluding the fountain, was soon joined by dozens of images that included the fountain, often used as a counterbalance for the bell tower, and the multiplication of such shots indicated a certain appreciation on the part of the public, which evidently bought and mailed them. A few rare examples elevate the fountain to the rank of subject, limited episodes, but over the decades, thousands upon thousands of these souvenirs travel the world, contributing, little by little, to the fountain’s entry into the collective imagination as an inescapable element of the urban landscape of the Piazza dei Miracoli.

The real triumph of the Three Putti, the complete reversal from the ancient desire to erase them from the landscape, finally arrives in the narrow contemporary, in the years of the technological revolution, The Age of the Image (I steal the definition from a discussed essay by Stephen Apkon in 2013), the era in which the image becomes a mass language thanks to technology. The proliferation of smartphones, equipped with ever more sophisticated cameras, and the immediacy of sharing on social-networks, has led to an exponential growth in the number of photographs taken each year in the world, a figure that has more than doubled in the last four years, to well over the frightening figure of a trillion, numbers that have more zeros than an IBAN code (18 to be precise).

In this new context we all become creators of images, we communicate through purely visual means, and if there are more than three million visitors who climb the Tower of Pisa every year, we can get an idea of how many shots are daily dedicated to the most classic shots in the Piazza dei Miracoli; and then just a search on Instagram, but also on Google, Facebook, Tumblr is enough to touch upon the new popularity of the Cybei group. If what prevails are the infinite ways in which tourists can play with the perspective of the Leaning Tower at arm’s length, the views that include the fountain seem second only to selfies of tower-bearers; beyond the numerical consistency of the phenomenon, which it seems useless to want to quantify exactly, the datum on the enormous popularity of the work is glaring. The presence in theinquadratura of the fountain, does not seem a casual presence, but a functional choice, recognizing the value of the group as a scenic backdrop, a visual reference, a focal point on which to converge the perspectives of the most famous monuments. The audience spontaneously explores the possibilities offered by the different viewpoints, enhanced in the continuous movement of the large putti, revealing an extremely modern, ultimately ingenious, almost visionary character of the work in its dialectical, but never static, relationship with the surrounding monuments. And here everything becomes playful, not as desecrating as the tower-holding pose, but playful nonetheless, considering the fun with which the improvised (or not) photographers play on the relationships of light and shadow, on whether or not to enhance the contrasts, on the relations of the group with the tower or on the famous framing with dome and bell tower, those who close the composition by also framing the baptistery in the era of Cybei images speak to us in a language that obtains universal and spontaneous understanding. This continuous flourishing of images is also beginning to be reflected outside the web, in the most diverse contexts, increasingly rooting the Three Puttos in the contemporary collective imagination.

In 2015, the fourth animated series dedicated to the legendary gentleman thief Lupin III was first broadcast, derived from the Manga by Japanese cartoonist Monkey Punch, which in turn was inspired by Maurice Leblanc’s short stories: Lupin III - lAvventura Italiana. Dusted off the legendary yellow Fiat 500 used in 1979 for the feature film The Castle of Cagliostro (not coincidentally directed by Hayao Miyazaki, a great fan of Italy) Lupin returned to the peninsula for an entire series, in twenty-six episodes, with an affair that would eventually feature none other than Leonardo da Vinci himself; the opening theme song was devoted to a long sweep through the clichés of tourism in Italy, from the Spanish Steps of Trinità dei Monti, to a canal in Venice, the Fortress of San Marino, the Panorama of Florence from Piazzale Michelangelo, and a beautiful shot of the Leaning Tower with the Fountain of Putti in fine evidence to counterbalance it, repeated of course at the beginning of each episode. To tell the truth, this was not Lupin’s first adventure set in Pisa: already in the second series, thepisode The Earthquake Factory (1977, on Italian TV in 1981) told of the mad scientist on duty and his blackmailing the government with the threat of an artificial earthquake, the target of which would be the city of Pisa and its famous leaning bell tower (not for nothing in the English-language version thepisode was titled Shaky Pisa). In that case, however, the fountain had magically disappeared from the view of the square, as if it had been invisible, an attitude diametrically opposed to the one held by the designers of the new series.

To conclude this roundup of the new popularity of the Cybei Putti, we go into a rather unusual place to talk about art, a true temple of popular culture: a Chinese mega market. Right here, among the labyrinth of aisles in which, according to legend, there is everything, the taste of the masses is measured, the orientations, including aesthetic ones, of what used to be called the man in the street are touched upon, and we come across once again, quite unexpectedly, the now iconic image of our Three Putti.

A recent (and very popular) series of paper gift envelopes, Made In P.R.C., is dedicated to major European tourist destinations, and if on the bag marked GB you’ll find the ever-present Big Ben, and below a capital-lettered FRA towers the unmistakable silhouette of the Tour Eiffel, the envelope dedicated to our country, ITA, is brightened by a winning Tower of Pisa/Fontana dei Putti pairing, by now a real must. For the usual series there are also other themes dedicated to travel, with evocative phrases (When I think of you the miles between us disappear), postmarks from around the world, American stamps, English telephone booths and the ever-present postcard from Pisa with the white of the Putti and the tower hurling itself against the unreal blue sky.

|

| Postcards from Pisa with the Fountain of the Putti |

|

| The Fountain of the Putti in a photo on Instagram |

|

| Collage with photos of the fountain taken from Instagram |

|

| The Fountain of the Putti in Lupin III |

|

| The gift packages with the fountain |

We have arrived at the paradox of a work that, after risking demolition and being covered with insults, comes to symbolize Italy on souvenir bags, in cartoon theme songs, and at the perhaps unique case of a revaluation that does not come through the words of a critic, the images of a film, the pages of a book, some high form of culture in short, but comes from below, from Instagram picture postcards and smartphone cameras.

The attributive affair has also had a complicated history, a reflection of the alternating fortunes of this troubled sculpture. Despite the fundamental testimony of a respected and very serious author such as Girolamo Tiraboschi, who as early as 1786, in one of his fundamental biographies of Cybei, listed among his works The Three Puttos in the Piazza del Duomo in Pisa, the name of the author of the group had been lost in time, abandoned to oblivion and forgetfulness until very recently. Tiraboschi’s words had also been taken up by Marquis Giovanni Campori (1873) and Count Giovanni Lazzoni (1880), but the authorship of the work remained anonymous for a very long time, and ended up being traced solely to the author of the base, at least by Bellini Pietri’s Guide to Pisa (1913) and Giorgio Castelfranco’s 1931 essay, La Fontana di G. Vaccà in Piazza del Duomo a Pisa, in both cases with great confusion over the dates. Then, in 1990, the authoritative voice of Professor Paolo Roberto Ciardi seemed to have closed the issue, with the publication of the contract concluded in 1763 between the Operaio Quarantotti and Giuseppe Vaccà , from then on officially recognized as the author of the Three Putti. In the late 1990s, the discovery of an autograph by Cybei, in which he recounted that he had executed the group for the Pisan fountain, called everything back into question.

Imagine how the writer, then a student at the University of Pisa, felt in having to present to the highly esteemed (and much feared) Professor Ciardi, a dissertation refuting one of his theses, even disputing an ancient document...but that is another story, and part of the long and unfinished work of re-evaluation, rediscovery and knowledge of the work of Giovanni Antonio Cybei, the forgotten artist, the Ghost of Sculpture.

Reference bibliography

- Marco Frati, The Piazza del Duomo of Pisa. A Millennium of Miracles in Antonino Caleca (ed.), Il Duomo di Pisa, Pacini Editore, Pisa, 2014

- Stephen Apkon, The Age of the Image. Redefinig Literacy in a World of Screens, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2013

- Stefano Renzoni, Giovanni Battista Tempesti Pisan Painter of the Eighteenth Century, PhD Thesis, University of Pisa, History of the Visual and Performing Arts, Pisa, 2012

- Stefano Renzoni, Non omnis moriar. Sculpture in the Time of the Lorraines, in Romano Paolo Coppini, Alessandro Tosi (eds.), Sovereigns in the Garden of Europe. Pisa and the Lorraine, exhibition catalog (Pisa, Palazzo Reale, May 10-July 20, 2008), Pacini Editore, Pisa, 2008

- Andrea Fusani, Dal Choro alla Bottega. New acquisitions on Giovanni Antonio Cybei, in Commentari dArte, 14, Year V 1999, Rome, 2003

- Mario Noferi, La Fontana dei Putti della Piazza del Duomo di Pisa, Felici Editore, Pisa, 2001

- Andrea Fusani, Lo Studio e lAccademia. Giovanni Antonio Cybei and the Carrara of the eighteenth century, Degree Thesis, University of Pisa, Degree Course in Conservation of Cultural Heritage, a.y. 2000/2001

- Roberto Paolo Ciardi, The second half of the century, in Roberto Paolo Ciardi (ed.), Settecento pisano: pittura e scultura a Pisa nel secolo XVII, Cassa di Risparmio di Pisa, Pisa, 1990

- Stella Rudolph, entry Cybei, Giovanni Antonio, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol.31, Istituto Treccani, Rome, 1985

- Giorgio Castelfranco, La Fontana di G. Vaccà in Piazza del Duomo in Pisa, in Rivista dArte, XIII, Florence, 1931

- Augusto Bellini Pietri, Guida di Pisa, Pisa, 1913

- Carlo Lazzoni, Carrara e le sue ville, Tipografia Drovandi, Carrara, 1880

- Giuseppe Campori, Memorie biografiche degli scultori, architetti, pittori, ecc, natives of Carrara and daltri luoghi della provincia di Massa, Tipografia Vincenzi, Modena, 1873

- Alessandro Da Morrona, Pisa Illustrata nelle arti del disegno, Livorno, 1812

- Girolamo Tiraboschi, Notizie depittori, scultori, incisori, architetti nati negli stati del Duca di Modena, Modena, 1786

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.