Pietro da Cortona's The Triumph of Divine Providence, a fundamental text of 17th-century art

When, in August 1623, Maffeo Barberini (Florence, 1568 - Rome, 1644) ascended to the papal throne with the name of Urban VIII, many intellectuals, scientists and artists rested their hopes on this learned and refined man, hoping for a cultural renewal of Rome and the establishment of an enlightened Church finally able to face serenely the challenges that its time posed before it. However, the pontiff’s choices did not take too long to disprove, at least in part, these expectations. Under his rule, in fact, the activities of the Roman Inquisition resumed with vigor, whose most illustrious victim was Galileo Galilei (Pisa, 1564 - Arcetri, 1642), tried in 1633 and forced to take theabjuration by the same sovereign who, until then, had defended and encouraged him, while nepotistic practices, which had always been widespread, reached with the Barberini family an exasperation generating heavy intolerance. Moreover, in 1641 the first Castro War began between the Papal States and the Farnese family, for control of the duchy located between Latium and Tuscany, a conflict that, among other things, led to an exacerbation of the tax burden on the Roman population and contributed to the deficit of about 30 million scudi left by Urban, at his death, in the papal coffers.

But, these facts aside, there remains no doubt that Barberini was one of the greatest and shrewdest patrons of the century. He profoundly affected the appearance of Rome, by then the capital of a state relegated to the margins of the seventeenth-century European political scene, and yet the seat of a Church of which he, resorting to the promotion of the arts as his main propaganda tool, strongly insisted on nurturing a triumphant image, tying it in a double thread with that equally grandiose image of his own household.

It should also be remembered that already as a cardinal Maffeo had distinguished himself by his solid cultural background and his lively and genuine love of art. He was, for example, among the first to sense and encourage the talent of the 20-year-old Bernini (Naples, 1598 - Rome 1680), who was to remain his favorite artist over the years. For two of Gian Lorenzo’s most famous sculptural groups, Apollo and Daphne and the Rape of Proserpine, commissioned by Scipione Borghese, Barberini had also devised some moralizing verses, engraved and still legible today on the marble bases.

Once pope spent a great deal of money on what was undoubtedly, during his reign but not only, Rome’s main building site, namely the new Vatican Basilica, the construction of which had been begun by Julius II in the first half of the 16th century. In fact, Urban VIII constantly monitored the progress of the work and pushed to speed it up, stipulating that the Congregation of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro (the commission of prelates in charge of managing the reconstruction and the various decorative interventions) should meet no longer three or four times a year, but every fortnight.

Throughout the seventeenth century, the basilica constituted an extraordinary laboratory, a place of comparison between the main artists and styles, as well as an extremely effective stage for the expression of Barberini patronage. To the aforementioned Bernini belongs one of the most famous and eloquent artistic creations of Urban’s pontificate, and of the Roman Baroque: the bronze baldachin executed for the church’s cross vault. The huge structure was inaugurated in June 1633 and placed to crown the papal altar and confession, which encloses St. Peter’s burial place. In dialogue with Michelangelo’s dome, under which it is placed, the canopy had at the same time the function of powerfully reaffirming the Petrine primacy from which papal authority descends, and of celebrating the person of Urban (to whom the numerous bees of the Barberini coat of arms inserted in the plinths, on the twisted columns and on the drapes of the upper part refer) as successor to the Apostle. Of course, alongside Bernini, many other artists were involved with various assignments in the Vatican undertaking; among them was the Tuscan Pietro Berrettini (Cortona, 1597 - Rome, 1669) better known as Pietro da Cortona, a painter and architect who arrived in Rome as a teenager in 1612.

In 1628 the congregation commissioned Berrettini to paint an altarpiece with the Holy Trinity as its subject , intended for the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament (one of the largest and most important in the building) and delivered probably at the beginning of the following decade. This was the first work executed by the artist for St. Peter’s Basilica, and was entrusted to him thanks mainly to the interest of Cardinal Francesco Barberini (Florence, 1597 - Rome, 1679). In fact, Guido Reni (Bologna, 1575 - 1642) had initially been chosen for the painting, with whom, however, the prelates had failed to reach a final agreement, thus finding themselves in the need to fall back on another author. It was in this context that the cardinal, who evidently enjoyed great authority as the pope’s nephew, proposed and succeeded in getting Pietro, who had long been one of his protégés, accepted.

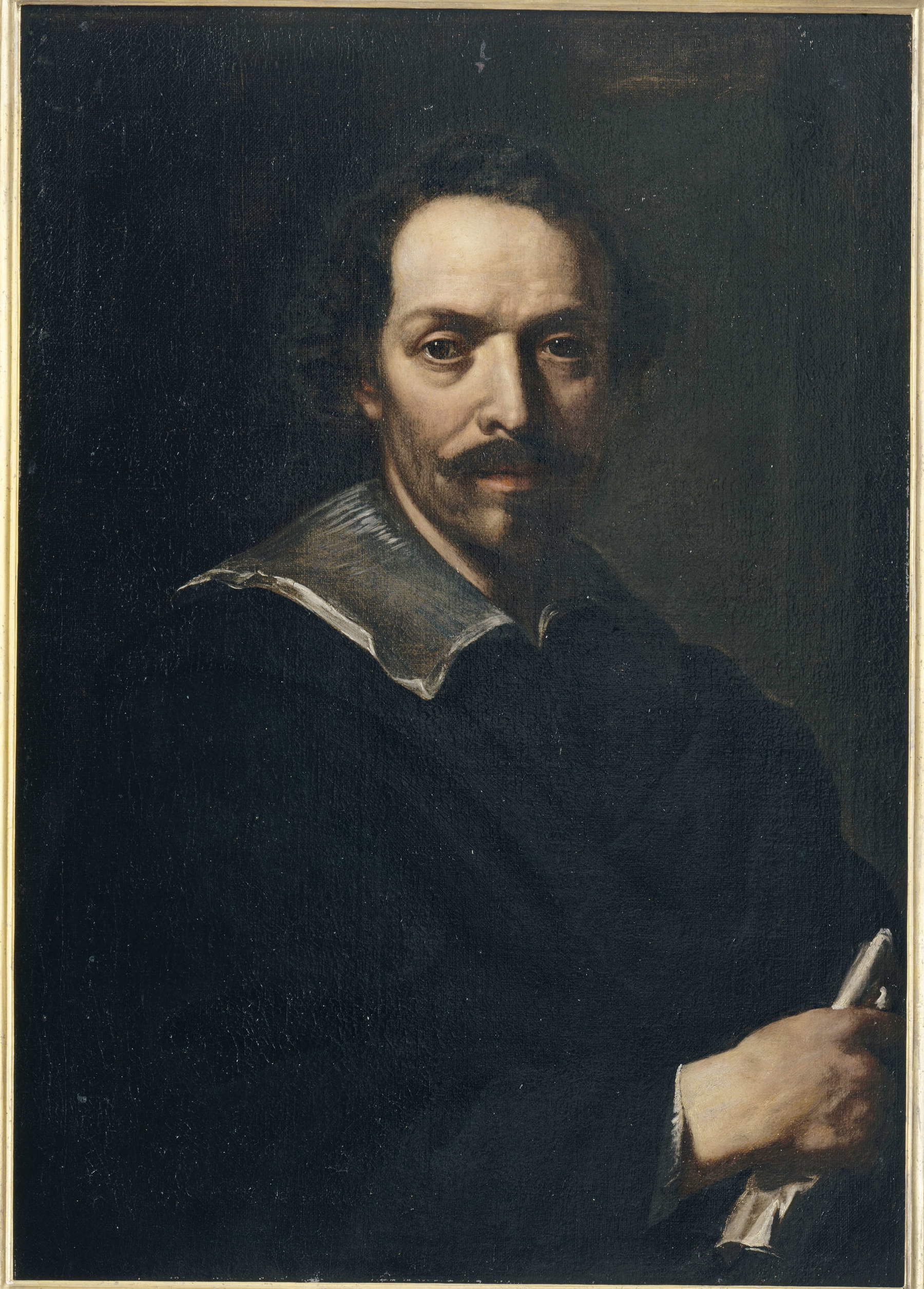

The Barberinis had come into contact with this young painter soon after Urban’s election, through the secret treasurer of the Apostolic Chamber, Marcello Sacchetti, for whom Pietro had already worked, and still would work, and to whom, in particular, he was about to make the intense portrait now in the Borghese Gallery. They had then obtained further proof of his talent on the occasion of the rebuilding of the early Christian church of Santa Bibiana on the Esquiline, commissioned by the pontiff for the Jubilee of 1625. Here the Cortonese had been asked to fresco the left wall of the nave with the depiction of episodes relating to the life and martyrdom of the saint, in collaboration with the more successful Agostino Ciampelli (Florence, 1565 - Rome, 1630) who had been assigned the right area.

The successful outcome of the undertaking, with which Berrettini had proved both that he had assimilated the heritage of Roman antiquities, long studied, and that he knew how to actualize history, through effective and passionate expressions and gestures, had marked his definitive affirmation in the artistic scene of Rome and the beginning of the prestigious professional link with the reigning household. As Giulio Briganti pointed out in the 1660s within his monograph dedicated to the painter, however, it is starting with another work, the canvas depicting the Rape of the Sabine Women, executed around 1629 and now preserved in the Capitoline Museums, that we observe “the first spectacular statement of Roman Baroque methods in painting.”

By now only a few years after the cyclopean fresco with which Pietro was to decorate the vault of the salon in Palazzo Barberini, in the Capitolini canvas the composition, which although obviously remains enclosed within the limits of the frame, appears to be refinedly asymmetrical, overcrowded with figures arranged on several planes in depth, pervaded by a centrifugal and dramatic motion. In 1625 Cardinal Francesco Barberini purchased from the Sforza family the palace on the eastern slopes of the Quirinal, which today houses the headquarters of one of Rome’s two National Galleries of Ancient Art, but was then intended to serve as the official residence of the pontiff’s family. Carlo Maderno was initially commissioned with the transformation of the building; however, the architect died only a year after the work began, which was then entrusted to Bernini, with interventions by Francesco Borromini and Pietro da Cortona himself.

It was Bernini who, compared to the initial project, enlarged the size of the reception hall on the piano nobile, which incorporated the space reserved for the loggia originally planned for the façade (later replaced with the mock windowed loggia). The masonry work for the vaulting of the room was completed in September 1630, and the following year work began on the scaffolding necessary for the creation of the fresco. The biographer Giovan Battista Passeri (Rome, 1610 - 1679) in his Vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architetti che hanno lavorato in Roma, in his biography of the painter Andrea Camassei (Bevagna, 1602 - Rome, 1649), writes that at first the decorative work was entrusted to this very artist, who is also listed in the 1635 registers of the Academy of San Luca as “painter of the ecc.mo Prince Prefect” that is, of Taddeo Barberini (Rome, 1603 - Paris, 1647), nephew of the pope, who was appointed Prefect of Rome in 1631. Taddeo was head of the secular branch of the family, and at least until the middle of the fourth decade, he used the Palazzo al Quirinale with his wife Anna Colonna and together with his brothers, Cardinals Francesco and Antonio Barberini.

Even before work began on painting the salon, Camassei had already frescoed other rooms in the building, but so had Andrea Sacchi (Nettuno 1599 - Rome 1661), a protégé of Cardinal Antonio, and Berrettini himself, who had also intervened as an architect and had worked, as a painter, in a gallery in the palace and in the chapel, and who, as we have seen, enjoyed Francesco’s favor. Interestingly, by the way, all three artists had been involved a few years earlier in the fresco decoration at the Villa Sacchetti in Ostia. In the end it was Francesco, the eldest of the three as well as cardinal nephew, who prevailed, and the vault was entrusted to the Cortonese, flanked by his pupils Pietro Paolo Baldini, Giovanni Maria Bottalla and Giovanni Francesco Romanelli. According to Passeri, however, the pope himself intervened in the family dispute and it was he who made the final decision; many scholars tend to consider this information reliable in view of the weight such a pictorial intervention would have had. Evidence of how much the pontiff had invested in the project (also) in terms of expectations are his daily visits to the salon during the work, which German painter and art historian Joachim Von Sandrart (Frankfurt am Main, 1606 - Nuremberg, 1688) writes about in his text Teutsche Akademie of 1675. In any case, the work went on for a long time: Peter began painting the ceiling in late 1632 and finished it at the same time in the year 1639. Although the area to be covered measured as much as 24 meters long by 14.5 meters wide, and was therefore very extensive, the numerous commitments that the painter had to manage certainly also affected the time.

When Cardinal Giulio Sacchetti left for Bologna in June 1637, Berrettini followed him and stayed several months in Florence to do the first two frescoes for the Sala della Stufa in the Pitti Palace, at the request of Grand Duke Ferdinand II (Florence, 1610 - 1670); then he left again for Venice and returned to his work in the Barberini salon only in December. And many more were the commissions he received over those seven years. It should be added, then, that at the time of his return to the Roman palace, the artist probably performed considerable remakes of what he had concluded before the trip, we do not know for sure whether because of his second thoughts or because of technical problems related to the poor cohesion of the mortar. Doubt also remains because of the fact that few preparatory drawings have come down to us, moreover dispersed among various domestic and foreign collections, so precisely defining the various stages of conception is rather arduous. The art historian Lorenza Mochi Onori in her essay Pietro da Cortona for the Barberini reports that during her time as director of the Gallery, during some restoration work, she could ascertain the presence of few carryover engravings from the cartoons and the absence of dusting. The fresco, therefore, was made for the most part by translating freehand, with broad brushstrokes, the images directly from the preparatory drawingsî. This modus operandi (also mentioned by the sources of the time) in addition to testifying to the artist’s great skill (especially in managing the proportions of the individual pictorial pieces in relation to the rest of the composition) could explain the scarcity of sheets with drawings in our possession today: one of the plausible hypotheses is that they were not collected, because having been employed directly on the building site they might have suffered damage, making their preservation useless in the eyes of contemporaries. Moreover, the days of work found by observation of the plaster are many, some of which were very limited and aimed only at correcting details that, evidently, on observation from below, were not executed perfectly. Drywall interventions, on the contrary, are decidedly meager.

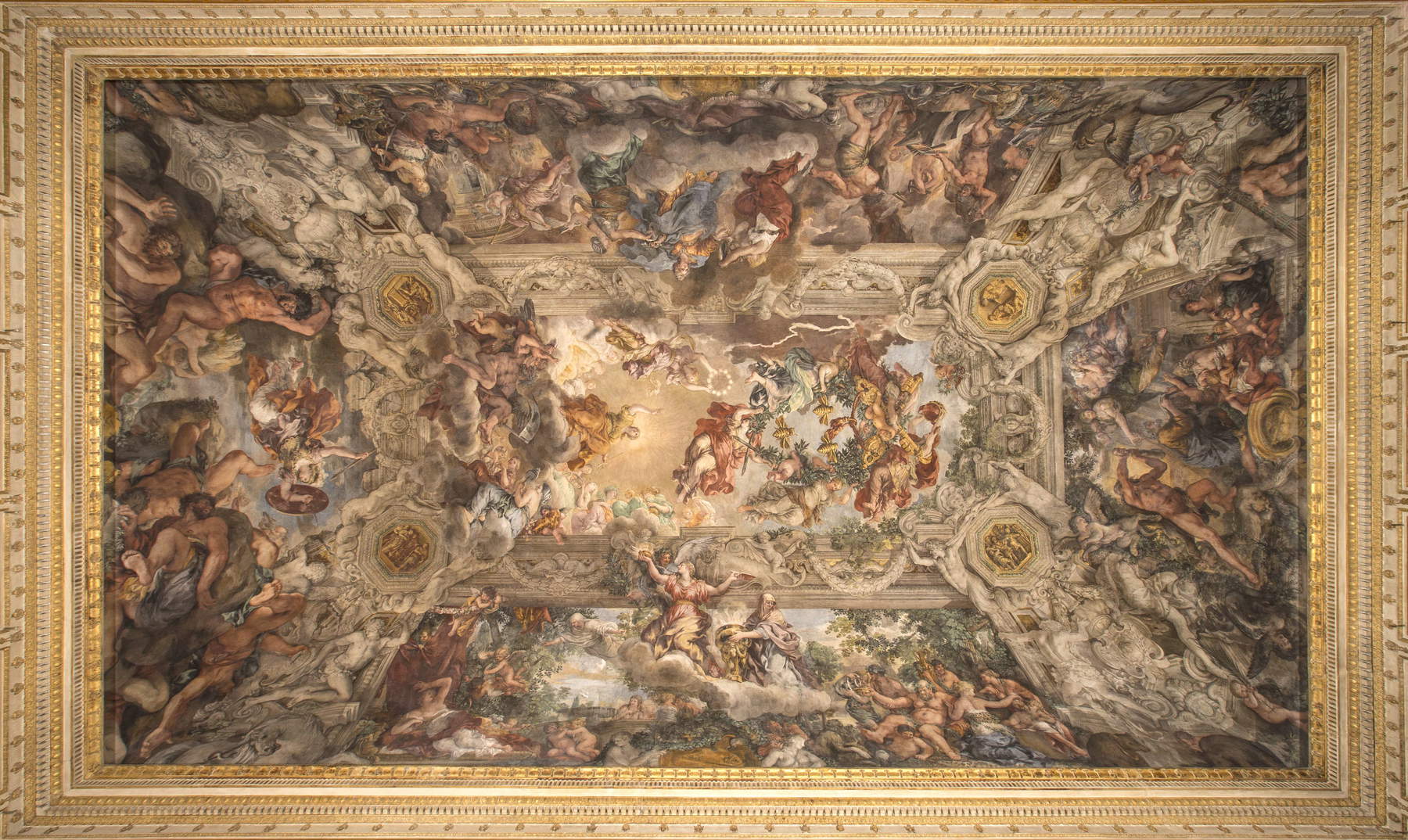

In any case, despite the long wait, the final result left the patrons more than satisfied. The fresco, depicting The Triumph of Divine Providence and the Fulfillment of its Ends under the Pontificate of Urban VIII Barberini, is a highly effective “temporal glorification of papal power,” as Mochi Onori notes, again. The iconographic program was developed by the ruling family’s court poet, Francesco Bracciolini, from a poem he himself had written, a few years before the pictorial interventions began, dedicated to the pontiff and entitled L’elettione di Urbano Papa VIII. The man of letters, who was also granted the privilege of flanking his surname with the words “Dell’Api” in reference to the Barberini heraldic bees, dictated to Pietro da Cortona the main subjects, which, then, the painter adapted and, in some cases, modified.

Bracciolini recounts in the poem a long battle, set in the days between the death of Gregory XV and the appointment of his successor, which ends happily with the victory of virtue over vice and, indeed, the rise of Urban VIII. The text is characterized by the fusion of mythological narrative, epic-allegorical, pastoral fable, biblical and historical exempla, chronicle of contemporary events, and fictional biography, and all this historical and literary heritage is actualized, transferred to the present, and inserted into the realization of the design of Providence in the time of Urban. In the poem God himself promises and, in conclusion, grants the election of the Barberini, who is celebrated not alone, but together with his family members: power descends from the divine will and is embodied in a specific worldly dynasty. Thus, looking back at the fresco, the three giant bees of the coat of arms of the household appear in the center of the flat mirror of the vault, enclosed in a large laurel wreath, which in turn is supported by the personifications of Hope, Charity, and Faith, and on which Rome and Religion are laying, respectively, the papal tiara and the Petrine keys. From one corner, a putto leans out offering a smaller garland, in reference, probably, to Urban’s passion and talent for poetry. Further down, another female figure, Divine Providence, reclining on fluffy clouds and surrounded by a warm glow that underscores her primary role, with scepter in her left hand, commands Immortality to adorn with a crown of stars the blazon composed of the three monumental insects. Below them, alluding to the inexorable passage of time are Chronos, devouring one of his children, and the three Fates, intent on weaving and then cutting the thread of human destiny.

As can already be guessed from this initial description, alongside figures drawn from mythology, many allegorical ones appear, in the guise of placid and florid maidens, and some of them, the newly invented ones who could not count on a well-defined iconographic identity, were probably quite obscure to many of the visitors. The salon was open to anyone who showed up decently dressed and at certain times, which proves how effective the Barberini family thought those images were and how important their dissemination was; precisely in order to make the precious meanings understood and circulated, the household provided the hall with a kind of guide, the Declaration of the Paintings of the Hall of the Lords Barberini, which was followed by others.

The figures mentioned above twirl in the sky, over which the actual wall surface is illusionistically open, as if broken through. This central space is framed by an architrave painted in monochrome, in imitation of marble, supported by four pillars that identify, in the intradoses of the vault, as many lateral areas. The latter house scenes alluding to the actions and virtues of the pontiff, whose actions and virtues, therefore, are placed ideally, but also physically, at the base of the apotheosis of his household that is willed and ordained by Providence. On one of the short sides of the room, the one facing the façade, Justice with the lictor, and Abundance holding a cornucopia laden with fruit, fly over a crowd of old men, women and children reaching out toward them; next to them Hercules drives away a harpy after having already killed another, lying at his feet. The pictorial figuration of the other short side shows, with Minerva routing the giants by causing them to fall (remarkable are the glimpses of the three figures on the right, who seem to be literally crashing down on the viewer), the victory of intelligence over brute force. Fronting the entrance (coming from the staircase designed by Bernini), on one of the two long walls, is a celebration of the pontiff’s love of knowledge, which he would therefore always have pursued, albeit within the sacred limits of religious orthodoxy that seem to be clearly reaffirmed here.

We see a female figure, Wisdom, wrapped in a golden robe bathed in light and seated on the clouds, with fire in one hand and an open book in the other, as, accompanied by Divine Help, she ascends toward the center of the vault, surpassing the limit of the architectural frame, for it is only up above, in heaven, that true knowledge resides. To reinforce this concept, Religion appears on her left, guarding the sacred tripod and her head is veiled, as does Purity hovering on the other side, holding a white lily. Remaining below them, however, are the vizî: Silenus, debauched, fat and inebriated, surrounded by nymphs and bacchae, and Venus who discreetly, sprawled limply on a red drape, watches with discouragement the battle of cherubs, symbolizing the struggle between Sacred Love and Profane Love.

On the long side on the opposite side, Urban’s policy of peace is extolled, which, according to historical facts, however, he succeeded very well in propagating, somewhat less in implementing. In the center we see Peace, wearing a blue cloak, also seated on a throne of clouds and also superimposed on the lintel, holding the caduceus and a key. She is flanked by Prudence, cloaked in red, holding a mirror, and another unidentified female figure, with a message in her hand, portrayed with her back turned and in the act of heading toward the temple to her right. Here Fame blows trumpets and a maiden in flight with an olive branch in her hand is closing the door of the temple of Janus shrouded in flames (its doors in ancient Rome were closed during times of peace) perhaps obeying the order contained in the message alluded to. Below, the Fury, naked, lies on the ground chained by the smiling Mansuetude, and on the other side Vulcan, surrounded by thick black smoke that seems to spread and encroach, almost to the point of lapping at the bees in the frame above, forges no longer weapons but a shovel.

Let us turn, finally, to the painted architectural frame, which punctuates the pictorial space, and is richly decorated with faux sculptures depicting floral festoons, bucrania, dolphins, ignudi, tritons, and putti. At the corners of the architrave, above each pillar, we see four clypeus with gilded faux bronze reliefs, which unfold episodes from Roman history, alluding to virtues attributed here to Urban VIII; they are also illustrated by the animals painted further down at the bases of the pillars. Thus we recognize the scene with The Prudence of Fabius Maximus to which is connected the bear, both symbolizing sagacity, The Continence of Scipio with the liocorn, representing purity, above the lion, symbol of strength, we have The Heroism of Mucius Scevola, and finally The Justice of Consul Manlius with the hippogriff, figuring perspicacity.

More than a hundred characters populate the fresco, each of them intent on the accomplishment of an action, in an uninterrupted whirlwind that obliterates real space and overwhelms even the fake architecture. This motion that pervades the entire surface is indulged and accentuated by the use of stippling: small dots of color are added to the painted surface, tone on tone, again in fresco, which, combined with a grainy surface obtained by employing more sand than mortar in the plaster, makes the pictorial material vibrant, almost iridescent. Within the central perspective, then, those related to each scene open up, yet the fresco in its entirety is conceived to be initially “embraced by a single gaze and to that immediately express the accomplished and unified sense of its invention and meaning,” as Briganti points out.

And if at first pure amazement prevails for the immense illusionistically generated spatiality, for the quantity of figures that animate it and, ultimately, for the technical skill that all this presupposes, later, as we have seen, we become aware of the complexity of the meanings conveyed by the fresco, to which the wonder aroused in the viewer confers further strength and effectiveness. It is precisely this desire to amaze and emotionally involve the viewer that is one of the most evident and most innovative features of the stylistic current that invested Roman art from the 1730s onward.

The fresco in Palazzo Barberini constitutes, in fact, one of the initial moments and one of the happiest expressions, in painting, of that artistic language that began to be defined precisely under the Barberini pontificate, to which only from the late eighteenth century, and with derogatory intent, did the neoclassicist theorists assign the name “Baroque.” By this term they meant to define a style that, in their view, from the fourth decade of the seventeenth century had distorted all the arts, dominated by the bizarre, by excess, tending to distort every principle of symmetry and correspondence, a style that the art critic Francesco Milizia, in his text Dell’arte di vedere nelle belle arti of 1781, went so far as to call a “plague of taste.” Nonetheless, it was precisely such eighteenth-century critics who first identified, clearly, albeit for the purpose of condemning them, the characteristics, the elements of novelty, as well as the main exponents of the Baroque stylistic current. Indeed, as they observed, Bernini and Berrettini, along with Borromini, were the major interpreters of this new sensibility; Anna Lo Bianco writes in her Pietro da Cortona and the Great Baroque Decoration that Pietro and Gian Lorenzo had “the same conception of art, vital and heroic at the same time, which comes to make the baggage of classical knowledge pulsate through the use of a reckless technique that forces lines, exasperates expressions, confuses volumes and colors.”

Urban VIII did not fail to sense and support the talent of these two artists and the persuasive force of their personal declinations of what was the Baroque language, using them, as we have seen, in the context of his political project, which had in the Vatican Basilica and the family palace its pillars, and through which he aimed, successfully, to reaffirm the cultural primacy of Rome, making it an instrument of hegemony for himself and his household.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.