When confronted with a self-portrait, the most intimate genre to which an artist can devote himself, the observer eager to grasp the essence of the painting is often led to wonder whether that painter or sculptor, at the moment he decided to entrust his image to canvas, marble, bronze, wore a mask, projecting onto the support a particular dimension of himself in order to let through a very specific message, or whether he simply placed himself in front of a mirror to offer of himself an unfiltered, sincere image, capable of touching the observer deeply in order to convey to him a state of mind felt at that moment, a synthesis of his character, an aspect (or several aspects) of his temperament. So, is a self-portrait a mask or a mirror? The answer becomes little easy when one is faced with the portraits of Pieter Paul Rubens (Siegen, 1577 - Antwerp, 1640), the painter who perhaps more than any other embodied the soul of the Baroque. His is a vigorous, dynamic and exuberant art, full of tumultuous battles, florid goddesses of antiquity, rubicund characters populating festive allegories, powerful and dramatic religious scenes. And he was a painter endowed with a “solemn narrative skill,” scholar Anna Lo Bianco has written, that “provokes a strong impact in the viewer, animated by a new feeling of engaging participation,” able to create compositions where “everything is animated by a strong sense of pathos and vital energy.”

A force that, on the surface, would almost seem to contrast with the temperament of Rubens, who is described to us by the sources as amild-mannered painter with an accommodating and friendly manner. The German artist and art historian Joachim von Sandrart (Frankfurt am Main, 1606 - Nuremberg, 1688), who got to know Rubens in 1627 during a trip from Utrecht to Amsterdam, described him in his Teutsche Academie (a large dictionary of art with biographies of a great many artists) as “in seinem laboriren expedit und flei�?ig gegen jederman höflich und freundlich bey allen angenehm,” meaning “quick and industrious in his work, cordial, friendly and pleasant with everyone.” Again, Raffaele Soprani, in his Lives of the Genoese Artists (Rubens often sojourned in Genoa, leaving several masterpieces in the city), writes that “the tasty and lively coloring of this valentuomo, his kindly stroke, the facondia of his speech, and the other noble endowments that graced him, so bound the spirits of the leading knights of this city, that they ill furnished their palaces without some table by him.” And even, the scientist Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, who was in correspondence with the Flemish painter, wrote that “there is no soul in the world more amiable than that of Mr. Rubens.” How does this contrast between the strength of his art and the extreme gentleness of his character emerge in the self-portraits?

|

| Rubens’ gaze in the self-portrait preserved at the Rubenshuis in Antwerp |

We know, meanwhile, of only four self-portraits by Pieter Paul Rubens. The last one in chronological order is surely the one preserved at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna: here, the artist paints himself past the threshold of sixty years of age (this is, in all likelihood, a work dating back to 1638, thus executed two years before his death) and, a unique case in the small number of his self-portraits, Rubens decides, at the end of his career, to depict himself in official tones. Indeed, the artist depicts himself near a column (according to an iconography typical of portraits of nobles and sovereigns: and typical of such types of portraits is also the three-quarter format), he carries a sword and wears a glove, all symbols of nobility and high social status: a unique case in the course of his entire activity, Rubens wants here to demonstrate how far his art took him. Yet, writes Wolfgang Prohaska in the Austrian museum’s catalog of paintings, “beyond the official poses, his features reveal a certain skeptical detachment, combined with a watchful, inquiring gaze.” Rubens thus shows himself to be reflective and, although posed in a dignified manner, he does not flaunt any pride (although he was nevertheless a rather proud man): it seems that his gaze almost wants to communicate to the viewer his indifference to the position that his proximity to the great European courts of the time had granted him, as well as his substantial impatience with high society. It should be recalled that, in 1630, the artist, having reached the threshold of fifty-three years of age, had married a sixteen-year-old girl, Helena Fourment, the daughter of a wealthy silk merchant, in his second marriage after the death of his first wife Isabella Brandt: Rubens, four years later, explained to Peiresc in a letter that although he had had the opportunity to marry an unspecified noblewoman, he had preferred to settle down with a girl from a family of more humble origins, because he did not intend to give up his precious freedom in exchange for a marriage to a member of the aristocracy.

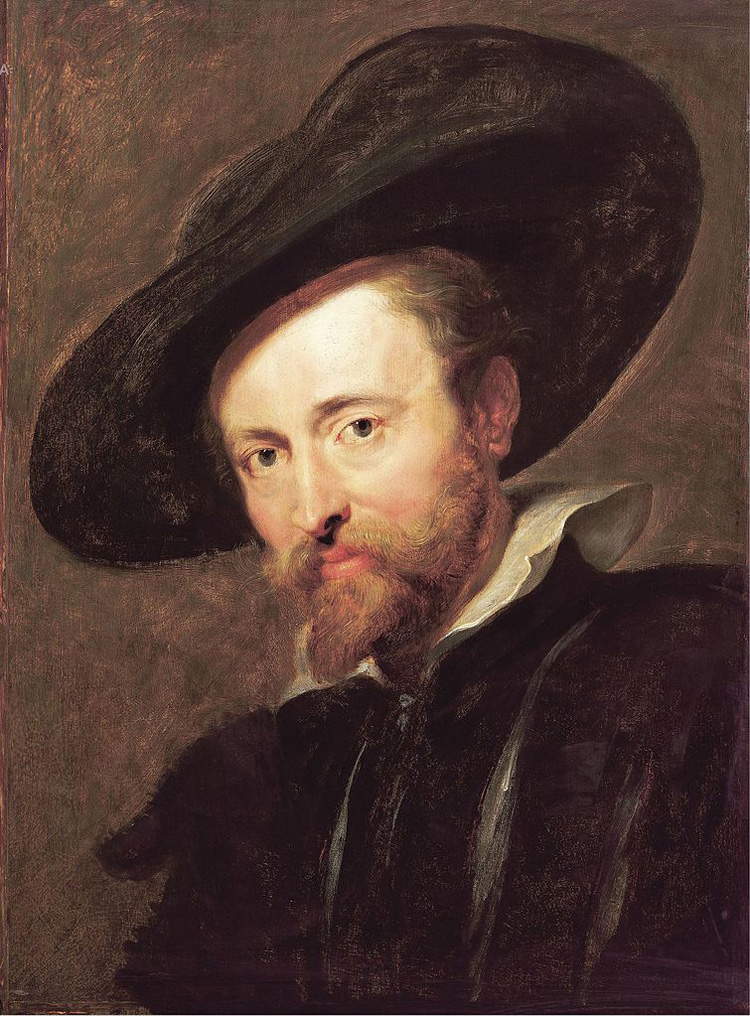

By contrast, it dates from 1623 (it is signed and dated) what is probably Rubens’s first self-portrait: it was executed for a prominent patron, the future King Charles I of England, then still Prince of Wales. Two years earlier, Rubens had sent a study for a painting to Henry Danvers, a knight and prominent member of the English court, but he equivocated about the work’s recipient, namely the prince himself. Since it was not possible to present the future king with a study instead of a completed work, Danvers asked Rubens to send another painting, and in particular requested a self-portrait of the painter.Rubens would later confess that he had been reluctant to send it, since he considered it immodest and improper to send his own portrait to a prince, but the firm will of the illustrious patron prevailed. Thus, the artist executed an almost resigned portrait: a black, sober suit, a large hat, and the gold chain, a symbol of the painting but also of the status he had achieved (he had been given gold chains as a token of gratitude by Archdukes Albert and Isabella of Austria in 1609 and by Christian IV of Denmark in 1623), almost hidden under the robe, as if the artist wanted to somehow promote himself by showing it but, at the same time, tried to avoid flaunting it. Not counting the replica of this self-portrait, now preserved in Canberra at the National Gallery of Australia, the two remaining self-portraits are the one in the Uffizi, the only one in which the artist depicts himself without a headdress (it can be dated to about 1628 and arrived in Florence in 1713 as a gift to Cosimo III de’ Medici from his son-in-law Giovanni Gugliemo II of the Palatinate-Neuburg), and the one now preserved at the Rubenshuis in Antwerp, perhaps the most fascinating of all.

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, Self-Portrait (c. 1638; oil on canvas, 109.5 x 85 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) |

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, Self-Portrait (1623; oil on panel, 85.7 x 62.2 cm; Windsor, The Royal Collection) |

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, Self-Portrait (c. 1628; oil on canvas, 78 x 61 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, Self-Portrait (c. 1630; oil on canvas, 61.5 x 45 cm; Antwerp, Rubenshuis) |

In the latter, Rubens still depicts himself in a dark suit, totally devoid of tinsel of any kind, gazing intently before him, his head covered by a large, wide-brimmed hat: it is likely that Rubens used these headdresses to conceal the incipient baldness we notice in the Uffizi painting, one of the rare vain concessions (if not the only one) to which the artist seems to indulge in his self-portraits. It is also a painting capable of blending a certain immediacy, noticeable in the way Rubens depicts his own robe and the background behind him (although there is no lack of those contrasts of light that had characterized his earlier achievements, especially the self-portrait in the Royal Collection), with that attention to detail that was peculiar to him and that is enhanced by the delicate light that the artist drops on his face to emphasize the blond accents of his beard, the expressiveness of his blue eyes, and the delicate colors of his skin. We do not know exactly at what period of his career the Antwerp self-portrait was made: however, it can be inferred from the similarities that it was made in the same years as the portrait sent to the Prince of Wales. It has been suggested that the execution of the work can be traced back to 1630, perhaps on the occasion of his marriage to Helena Fourment.

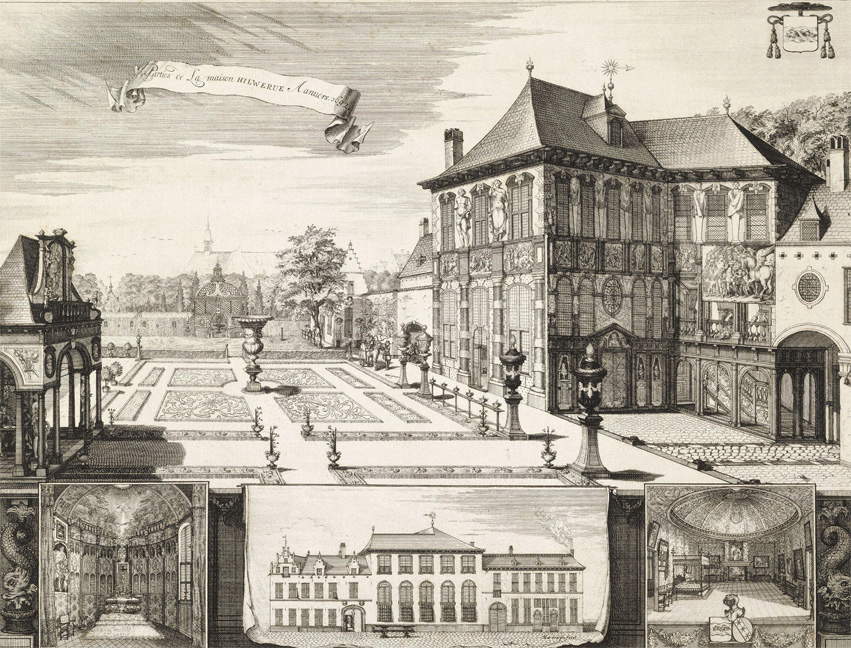

Of Rubens’s self-portraits that we know of, certainly the Antwerp one is the most informal, and this informality is most likely due to the fact that this painting was to constitute a kind of study or prototype for possible future more challenging and defined self-portraits. Consequently, we cannot even know with complete certainty whether the great spontaneity that permeates the painting was intentional, or simply whether the painting appears spontaneous to us because the artist had intended it as a sketch for more elaborate realizations. It is also likely that Rubens intended to make this painting for his own collection: in addition to being an acclaimed artist, Rubens was also a fine art collector, and he gathered his collection in his home, the Rubenshuis (“Rubens House”), today a visitable museum as well as one of the most interesting and best-preserved artist’s residences in Europe.

The painter bought the house in Antwerp, the main city of Flanders, in 1610: his goal was to make it his own residence, a studio in which he could work, as well as the home of his art collection. It was Rubens himself who oversaw the architectural renovations of the house, a typical Flemish brick dwelling, and it was he who drew the plans for that traditional house to become a palace that would echo the sumptuous residences Rubens had seen in his sojourns in Italy: it was precisely in Genoa that Rubens had had the opportunity to study in depth the palaces of the rolli, the residences of the city’s patriciate, so much so that in 1622 he drew up a book, The Palaces of Genoa, in which the artist had illustrated and described the city’s buildings in great detail (and it is a text of fundamental importance for the study and understanding of the palaces of the rolli of Genoa). Thus, Rubens ensured that the dwelling had a facade inspired precisely by Genoese palaces (unfortunately demolished in the late eighteenth century) and that it was equipped with a sumptuous inner courtyard developed on arches and large windows of classical ascendancy, adorned with statues, and to which was connected a large portico, modeled on the example of Roman triumphal arches and overlooking a lush Italian garden. It is precisely the portico, along with the garden pavilion, that is the subject of a restoration that began on September 18, 2017, and, pending completion set for early 2019, opened to the public during the Antwerp Baroque Festival 2018. Rubens Inspires: these are, moreover, the only two parts of the house that have not undergone heavy remodeling in subsequent eras, and thus constitute an invaluable living testimony to Rubens’ rare activity as an architect. The restoration, which follows the first conservative restoration conducted by Emiel van Averbeke between 1939 and 1946, the latter year in which the Rubenshuis was opened as a museum, was necessary because of the precarious state of preservation of the two architectural elements, aggravated by water infiltration. But that’s not all: in fact, the restoration will also remove some later additions, so as to restore the portico to its imagined state, exactly as Rubens had envisioned it.

|

| Jacobus Harrewijn by Jacques van Croes, The Rubenshuis in Antwerp (1692; engraving, 432 x 334 cm; Antwerp, Rubenshuis) |

|

| The portico of the Rubenshuis. Ph. Credit Rubenshuis Antwerp |

|

| The courtyard of the Rubenshuis. Ph. Credit |

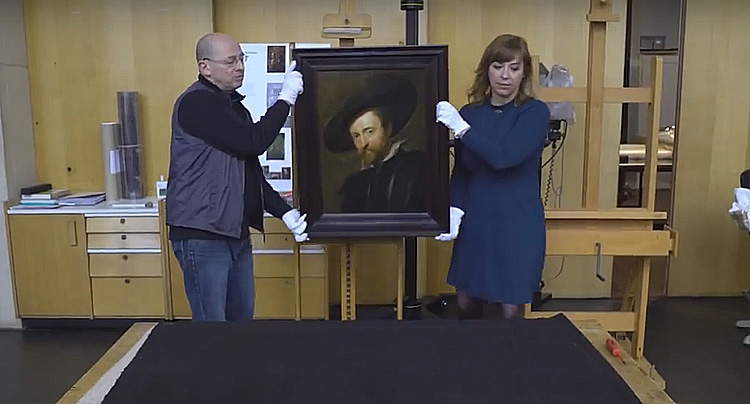

The Rubenshuis porch and garden pavilion are not the only ones undergoing restoration, however. In fact, the Antwerp self-portrait also underwent a recent intervention, which began in January 2017, when the painting was sent to the KIK-IRPA in Brussels (Koninklijk Instituut voor het Kunstpatrimonium - Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique, or “Royal Institute of Artistic Heritage”: it is the main institute for the restoration and conservation of cultural heritage in Belgium), which is destined to receive it for about a year: the painting’s return to Flanders is scheduled for June 1, 2018, the day set for the self-portrait’s return to the Rubenshuis and the opening date of the Rubens Returns exhibition, which in addition to displaying the restored painting also plans to show the public the Antwerp museum’s twelve new acquisitions.

However, this is not the first time that the work, at least in recent times, has left its home for investigation. It had already happened in 2014, when Rubens’ self-portrait was sent to the National Gallery in London, and specifically to its conservation and restoration department, for an initial analysis on the possibility of restoration: the intervention conducted at the time had ascertained the substantial fragility of the work, since Rubens, as precise as he was, was in the habit of making the supports of his paintings by joining several wooden planks together, a habit, however, that was risky for the painting’s state of preservation, since more planks joined together are more susceptible to alteration and deformation. However, restorers at the National Gallery have given a positive response for possible restoration. Thus the self-portrait, after being displayed in amajor exhibition at the Rubenshuis(Rubens in private. The master portrays his family, held between March and June 2015), which also featured portraits from the Royal Collection and Vienna (the one from the Uffizi, due to its state of preservation, cannot travel), was displayed for some time in its home before returning, in early 2017, to the hands of technicians. Before the actual intervention (about which no details are yet leaked), however, the self-portrait underwent diagnostic examinations aimed at gaining information: among them, also dendrochronological examination to obtain useful details around the dating of the painting (dendrochronological examination is in fact the one that allows to date an object through the study of its wooden elements) and X-ray fluorescence examination that allowed to understand how many and which parts were retouched and modified at later times, since it is certain that the painting underwent, throughout history, a change in format (in particular, the work was oval before becoming rectangular: however, we do not know for sure whether or not it was Rubens himself who carried out the rearrangements). It is also certain that the painting has undergone alterations to the paint surface, due to restorations often conducted without too many scruples. It is therefore probable, KIK-IRPA restorers speculate, that originally the work “was much more beautiful than we can imagine,” is what Marie-Annelle Mouffe, who along with other restorers from the Belgian institute is working on the intervention, said in an official Antwerp museums video. “From our findings,” her colleague Steven Saverwyns echoes, “we assume that the painting, after restoration, may look totally different. We need to assess how far the intervention can go.”

|

| Technicians remove Rubens’ self-portrait from its wall |

|

| The painting in the restoration laboratories of KIK-IRPA |

|

| Rubens’ self-portrait is disassembled |

|

| The painting undergoes diagnostic tests |

What, however, is the painter’s intended image of himself in this interesting self-portrait? It is the work that offers perhaps the image of the artist most closely adhering to his own courteous, polite and affable nature and noble soul, so praised by those who were fortunate enough to know him. The gaze is friendly, interested, curious, and the mouth, while remaining tight in a serious expression, seems about to let loose a barely hinted but nevertheless good-natured and sincere smile. This pleasant aspect that Rubens intends to communicate with what is probably the most intimate of his self-portraits, capable of restoring to us the idea of the true gentleman that the artist was, is entirely consistent with the descriptions of his personality handed down to us by his contemporaries. The work then acquires even greater fascination when one considers that, from the moment it was made, it has never left its home, except for temporary transfers. It is almost as if Pieter Paul Rubens never left his home and is still here among us, to show us the heights touched by his art.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.