Piero della Francesca's Madonna of Senigallia: the abstract poetry of light

It may seem strange, but we know of no ancient sources that mention one of the greatest masterpieces of the Renaissance, the celebrated Madonna of Senigallia by Piero della Francesca (Borgo San Sepolcro, 1412 - 1492). In fact, the first mention of what we can undoubtedly consider to be one of the Tuscan artist’s most important works dates back to 1822, and is contained in a letter sent by a scholar, Father Luigi Pungileoni, to Marquis Raimondo Arnaldi: the religious man had seen the work in the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Senigallia, in the Marche region, and had thought that it was a “wooden sketch” of the great Montefeltro Altarpiece, now housed in the Brera Art Gallery. Consequently, since the Montefeltro Altarpiece was believed at the time to be the work of Friar Carnevale, the Madonna of Senigallia was also attributed to the Urbino friar. The painting was in a decidedly precarious condition of legibility: probably the dirt that had accumulated on the pictorial surface over the centuries had dulled its quality, to the point that little attention was paid to the work by art historians.

|

| Piero della Francesca, Madonna of Senigallia (c. 1470-1480; oil and tempera on panel, 61 x 53.5 cm; Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche) |

It took thirty years before anyone formulated the name of Piero della Francesca: the first to make the suggestion was Gaetano Moroni. The Roman bibliographer, in his Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica da San Pietro fino ai giorni nostri, published in 1854, had spoken of a “small, very beautiful painting believed to be by Della Francesca, which represents the husband and wife Giovanni della Rovere and Giovanna di Montefeltro founders in the act of venerating the B. Virgin.” On the description drawn up by Moroni it will be necessary to return in a moment: first some further notes on the history of the Madonna of Senigallia are necessary. A history that continued with the reconnaissance carried out in 1861 by Giovanni Morelli and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, at the time of their trip to the Marche region, undertaken to catalogue the works of art in the region, under a commission given by the first government of united Italy. The two art historians had set the estimated value of the work at 2,500 liras (in fact underestimating it, considering that the Perugino altarpiece preserved in the same church was attributed a value of 150.000 liras) and they had been hesitant in the face of the name proposed by Gaetano Moroni: in the catalog compiled after their travels and published in 1891, they had described the Madonna of Senigallia as a “painting that has suffered much from the restorations” and that “can be attributed to Pietro della Francesca or to the so-called Frate Carnevale.” And it was precisely around these two names that all the major scholars of the late nineteenth century lined up: Gustavo Frizzoni and Costance Jocelyn Ffoulkes were in favor of an attribution to Friar Carnevale, while Jacob Burckhardt, Adolfo Venturi and Bernard Berenson were convinced it was a work by Piero della Francesca.

The studies that ascribed the work to Piero della Francesca multiplied after the cleaning operation was loudly called for in 1892 by Domenico Gnoli, who evidently understood the work’s importance and wished that an intervention could provide better conditions for legibility. In the meantime, the Madonna of Senigallia had also been stolen: it was on the night of October 27-28, 1873, when a citizen of Senigallia, Antonio Pesaresi, and a citizen of Jesi, Antonio Bincio, stole the work in order to sell it to an English collector who was evidently unscrupulous. The plan was foiled, however, and the work was recovered a few days later in Rome. It was not, moreover, the only theft that the Madonna of Senigallia experienced: a hundred years later, between February 5 and 6, 1975, the masterpiece (which in the meantime, in 1917, had been moved for security reasons to the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino, where it is still located today) was stolen, along with Raphael’s Flagellation and Muta in one of the most sensational art thefts in recent history (the works were fortunately found the following year in Locarno). Returning to attributional events, after the 1892 cleaning, the first confirmations began to arrive, including those of Felix Witting (dating from 1898) and William George Waters: the latter in 1901 proposed, as did many of his colleagues by then, that the painting be attributed to Piero della Francesca, although he considered it “one of the least attractive of his works.” Berenson, who in 1897 had considered the work to be by Piero’s hand, but with workshop help, reconsidered his positions in 1911 and attributed the entire authorship of the painting to the Biturgense master. Few voices were later voiced out of the chorus, and today, also following the restoration conducted in 1953 by Paolo and Laura Mora of the Central Institute for Restoration in Rome and directed by Cesare Brandi, the Madonna of Senigallia is unanimously assigned to Piero della Francesca’s catalog.

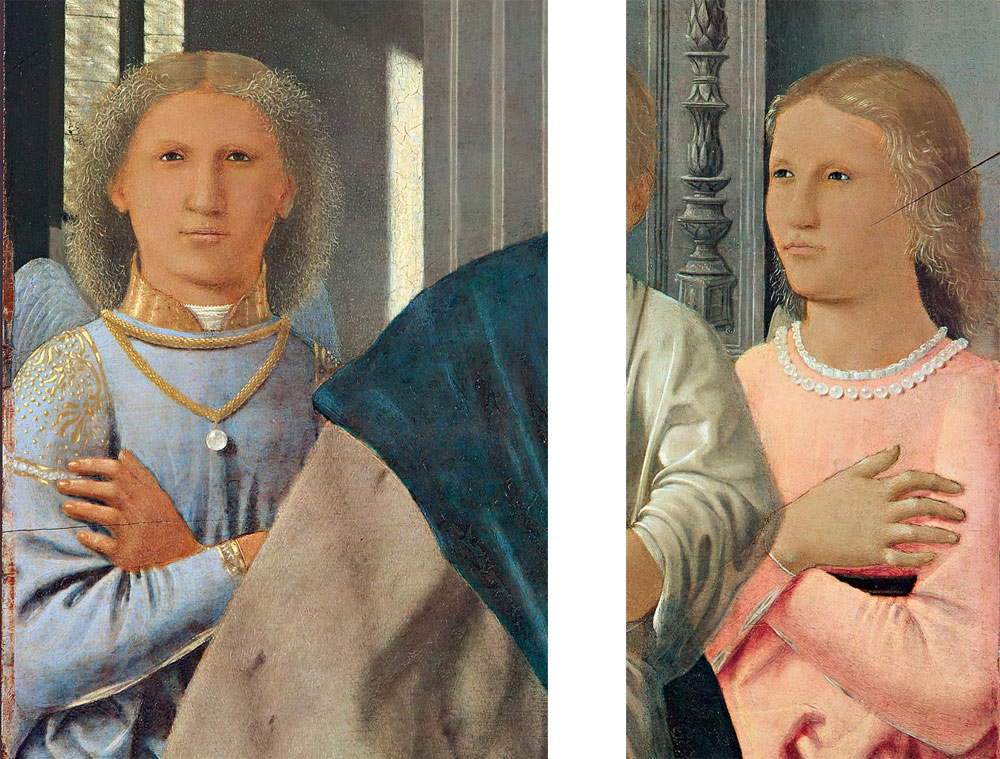

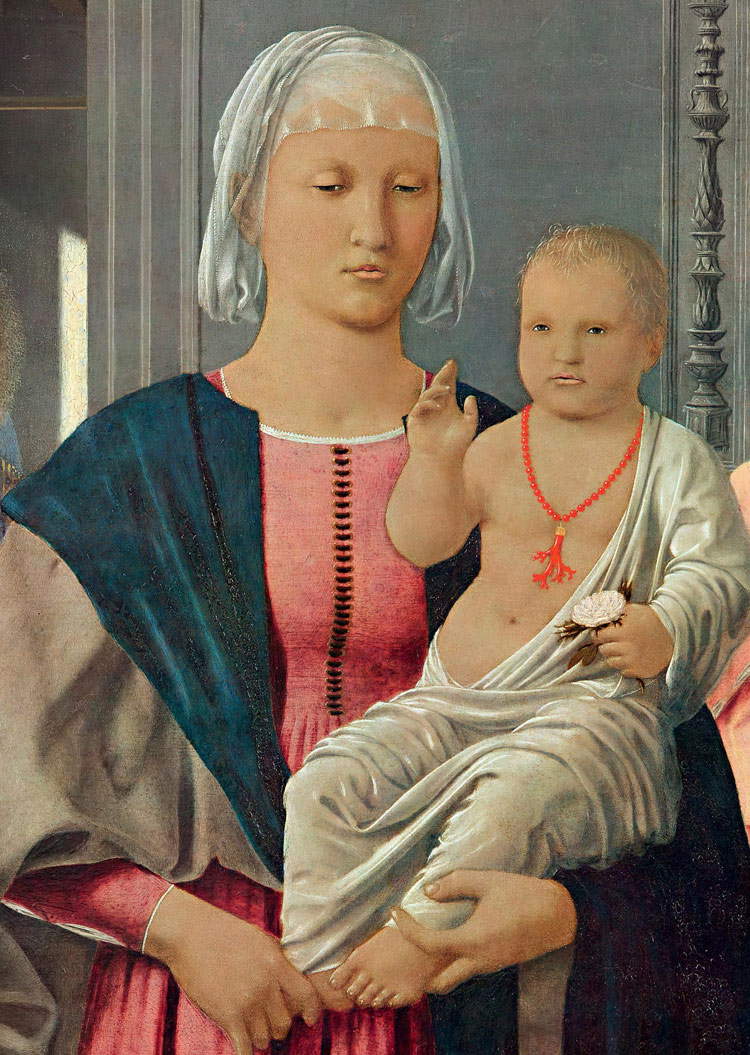

It is a work that stands out for its solemn hieraticism, typical of Piero della Francesca’s style and especially evident in the figure of the Child Jesus who, seated on his mother’s left arm, with a coral around his neck (a symbol of protection but also a reminder of the blood shed on the cross) and clutching a white rose in one hand (a reference to the rosary), addresses the gesture of blessing toward the viewer. On either side of the two main protagonists appear two figures in whom, as mentioned above, Moroni had wanted to identify the portraits of the lord of Senigallia Giovanni della Rovere and of the last member of the dynasty of the dukes of Urbino, Giovanna di Montefeltro: the noblewoman, by marrying Giovanni della Rovere, had guaranteed dynastic continuity to the duchy of Urbino, which after the death of her brother Guidobaldo da Montefeltro passed to Francesco Maria I della Rovere, the couple’s son. This was a most important marriage, for it came as the seal of an alliance between Giovanna’s father, the celebrated Federico da Montefeltro, and Giovanni’s uncle, Pope Sixtus IV, born Francesco della Rovere: an alliance thanks to which Federico had been able to obtain the title of Duke. The identification, which had fascinated Felix Witting himself to the point of inducing him to propose it again in his monograph dedicated to the Tuscan artist, was later deemed unacceptable by many (the characters would simply be two angels without more specific connotations, and moreover they are quite similar to those who had already appeared in the Montefeltro Altarpiece), but it had the merit of endowing the painting with a precise historical collocation. Indeed, it has been suggested that the work was commissioned on the occasion of the marriage between Giovanni della Rovere and Giovanna da Montefeltro, confirmed pro forma in 1474 and actually celebrated in 1478. Of course, we have no idea who the commissioner was: it has also been suggested that it might have been a gift that Federico da Montefeltro would have given to the couple. The work would later be placed in the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie, built in 1491 to a design by Baccio Pontelli and at the behest of the two lords: the construction was an ex voto of Giovanni and consort, who wanted to thank Our Lady for granting them a son, the future Duke Francesco Maria I, born in 1490.

|

| The two angels |

|

| The objects |

|

| The Madonna and Child |

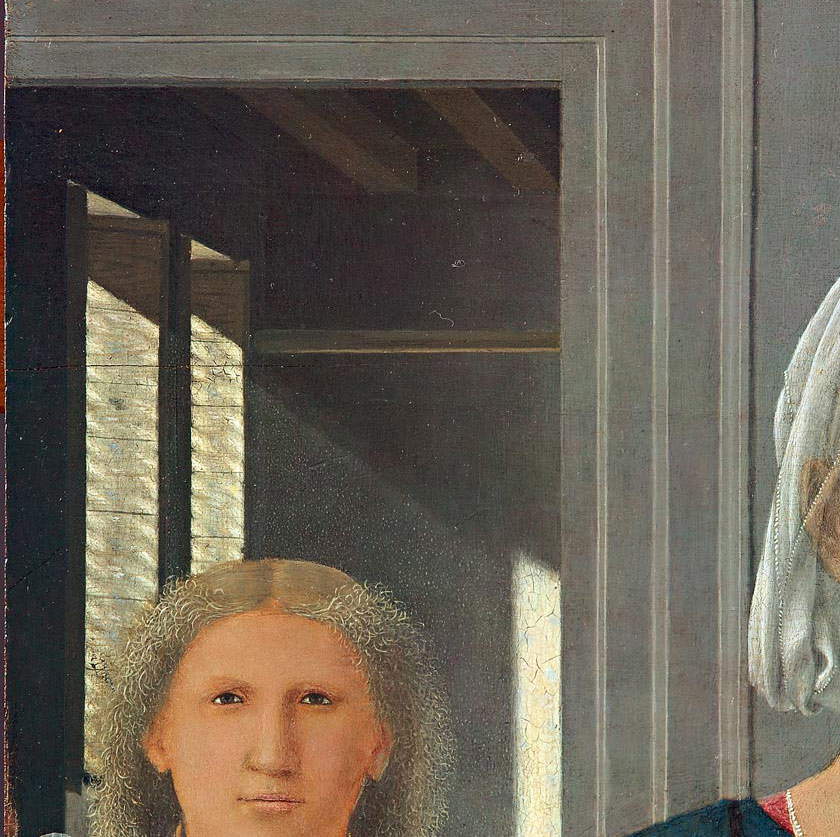

The Madonna of Senigallia is a work that is only apparently simple: in fact, all the objects that appear in it, even those related to the most mundane everyday life, are loaded with meanings that refer to themes related to faith and religion. The objects we observe are few in number, but they all have their own well-defined role: this at least according to the interpretation of Marilyn Aronberg Lavin, a scholar among the leading experts on Piero della Francesca’s art. Thus, the decoration on the niche behind the figures would depict an Easter candle, at the same time a symbol of death and rebirth, since Christ sacrificed himself to redeem humanity and, on Easter Day, by rising again defeated death. The box that appears on the top shelf would be a pyxis, the container for the consecrated host-a clear reference to the sacrament of theEucharist, instituted by Jesus the day before he was crucified. On the lowest shelf we see a wicker basket containing some veils: they would allude to Jesus’ burial. The door that opens onto the room in which we see the window through which light penetrates (one of the most striking pieces in the work) would be a reference to Our Lady: one of her attributes was in fact Porta Coeli, or “gate of heaven.” And the light itself alludes to the virginal conception of Jesus, since it would represent, according to Marilyn Aronberg Lavin, the “solemn essence that miraculously passed from divinity to the Child.” On the references to the conception of Jesus, Carlo Bertelli had also expressed himself, who wrote in his 1991 book that "the room without a doorway, which crossed by the light that enters between the shutters that have been pulled aside, is a favorite theme in Florentine iconography of theAnnunciation, which alludes to Mary’s cubicle in which the incarnation was accomplished." Bertelli thus traced back to Beato Angelico’sAnnunciation now in the Prado (and the lost precedent of Masaccio’sAnnunciation once in San Niccolò Sopr’Arno) as the original iconographic sources for the detail of the illuminated room glimpsed behind the door.

|

| The light from the window |

|

| Beato Angelico, Annunciation (1425-1428; tempera on panel, 194 x 194 cm; Madrid, Prado) |

A hypothesis (it is not known how well-founded, but nonetheless worthy of mention), first formulated by Maria Grazia Ciardi Dupré, has since come to light, according to which the Madonna of Senigallia could be a tribute by Federico da Montefeltro to his wife Battista Sforza, who had passed away when she was only twenty-six years old in 1472 (the date would thus be compatible with the period in which most think the painting was made, which given the obvious similarities with the Montefeltro Altarpiece should date precisely from the 1470s): the Virgin would thus have the features of a woman, and in the Child it would be necessary to identify a portrait of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro. Even in the architecture, which according to this reading would recall that of the Ducal Palace in Gubbio (a city that was part of the Duchy of Urbino and where Battista Sforza died), there has been a desire to see a connection with the story of Federico da Montefeltro’s wife.

What everyone seems to agree on instead is the fact that the work denotes Flemish suggestions. The luministic effects (such as the light that admirably brings out the dust near the window), the minutely described interior with its objects of daily use, the research into the technique of oil painting that precisely in the second half of the fifteenth century began to make its way into Italy-all these elements show that Piero della Francesca was familiar with Flemish painting. The Madonna of Senigallia has been repeatedly likened to Jan van Eyck’s Portrait of the Arnolfini couple, for all the qualities mentioned above, and we know that, in all likelihood, there was a painting by Jan van Eyck at the court of Urbino (or at least this is what Giorgio Vasari has handed down to us), but it is equally likely that Piero’s familiarity with Flemish art should not have come to him only from his stay in Urbino: a passion for the Norse was spreading throughout several Italian courts in the mid-15th century, and it is therefore safe to assume that the occasions Piero had to frequent Flemish art were not so sporadic. A scholar such as Liana Castelfranchi Vegas, however, took care to point out how the Tuscan artist had infused the painting with an originality all his own: typically Pierfrancesque would thus be “the poetry of the light that in luminous rivulets glides over the jambs and rummages through the basket of clothes” and “the splendid display of the four angelic figures aligned in the foreground and almost frontal.” And in lyrical tones Keith Christiansen also spoke of the Madonna of Senigallia: for him the painting “has impressed many observers (including Longhi) because it is a stunning prelude to those scenes of domestic life in 17th-century Holland painted by Vermeer [...]. And certainly there can be no doubt that, as in the work of the great Delft master, Piero too could benefit from a deep understanding of optical phenomena and the mathematics of perspective to achieve an effect of suspended atmosphere.”

These are precisely the same conclusions reached by Roberto Longhi, who left us one of the most profound and elegant analyses of the Madonna of Senigallia, which found in light one of the keys to interpreting the painting. “One is transfixed,” Longhi wrote, “at seeing the pure light oozed and gathered in these simple forms, and it seems almost as if the old synthetic sense after having suggested to Piero the theorems of form-color now adds to him those of the abstract form of light, which, as is well known, were to bear fruit so much later in painting. And when, finally, one senses how that roar of the sun on the wall, is united through the darkness, by a guide of dust, to the source of light, one wonders if in this conciliation, almost, of the infinitesimal with the volumetric, Piero does not extend, from his own time, his hand to those Dutchmen, who, two centuries later, founded the problems of lume sur una spaziosità learned from Italy: the De Hooch and the Ver Meer.”

|

| Jan van Eyck, Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Arnolfini (1434; oil on panel, 82.2 x 60 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Jan Vermeer, Young Man with Pitcher of Water (c. 1662; oil on canvas, 45.7 x 40.6 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| Pieter de Hooch, Woman Peeling Apples (c. 1663; oil on canvas, 67.1 x 54.7 cm; London, Wallace Collection) |

Reference bibliography

- James R. Banker, Piero Della Francesca. Artist and Man, Oxford University Press, 2014

- Keith Christiansen, Piero della Francesca. Personal Encounters, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014

- Antonio Paolucci, Carlo Bertelli (eds.), Piero della Francesca e le corti italiane, exhibition catalog (Arezzo, Museo d’Arte Medievale e Moderna, March 31-July 22, 2007), Skira, 2007

- Maurizio Calvesi, Piero della Francesca, Rizzoli, 2001

- Maria Grazia Ciardi Dupré, La Madonna di Senigallia nel percorso di Piero in Paolo Dal Poggetto (ed.), Piero e Urbino, Piero e le corti rinascimentali, exhibition catalog (Urbino, Palazzo Ducale e oratorio di San Giovanni Battista, July 24-October 31, 1992), Marsilio, 1992

- Carlo Bertelli, Piero della Francesca. La forza divina della pittura, Silvana Editoriale, 1991

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.