Piero della Francesca's Madonna del Parto, one of the most beautiful images of motherhood

An intense and profound scene from Valerio Zurlini’s 1972 film La prima notte di quiete stars Alain Delon, who plays the role of Professor Daniele Domenici, and Sonia Petrova, who plays his student Vanina Abati in the film: the two young people find themselves in front of Piero della Francesca ’s Madonna del Parto (Borgo San Sepolcro, c. 1412 - 1492), of whom Alain Delon provides a dense and poetic description, imagining the great Renaissance artist’s Virgin as a “sweet adolescent peasant girl, haughty like the daughter of a king,” distracted from her daily activities, perhaps the flock she was tending, to be called upon to model for the mother of God. “Perhaps,” the actor wonders, “she already feels darkly that the mysterious life that day by day grows in her will end up on a Roman cross, like that of an evildoer.” And the vision of the Pierfrancesque masterpiece inspires his student to reflect on what motherhood is:“Two who love each other. Here, perhaps. Because otherwise all that remains is a body that is deformed. All that remains is discomfort. The sorrow. The cruelty of people who begin to notice. With nothing left to do. Or almost.”

Piero della Francesca’s work, preserved today at the Museo Civico della Madonna del Parto in Monterchi, Valtiberina, has fascinated generations of scholars, writers, and filmmakers. One need only think also of the scene in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalgia , which with Zurlini’s film has one element in common, namely that neither scene was shot in front of the real work: in The First Night of Stillness it is a reproduction installed for the occasion inside the parish church of San Pietro a Ponte Messa, near Pennabilli, in Romagna, while in Nostalgia the work is reproduced in the church of San Pietro in Tuscania. It is that in Nostalgia the scene, also famous, in which the protagonist Eugenia, played by Domiziana Giordano, enters the church and sees some women reciting a litany for the Virgin, and asks the sacristan why women are more devout than men, getting as an answer a remark that expresses an essentially macho view of the matter (“a woman is needed to make children, bring them up, with patience and sacrifice”), to which Eugenia replies in a proudly sarcastic manner (“And is she not needed for anything else, according to you?”). Muriel Spark, Piero Calamandrei, Ingeborg Walter, Roberto Longhi and many, many others have since spoken about the Madonna del Parto . It is probable, indeed, that it was Longhi himself who inspired Alain Delon’s short monologue, with the elegant writing of the monograph published in 1927 by Valori Plastici: “Solemn as a king’s daughter under that ermine-suppressed pavilion, she is nevertheless rustic as a young mountain girl coming to the door of the charcoal kiln. From one hand upturned on her hip, from the other hinting at her lap, both studded and woody, arise gestures of melancholy purity.”

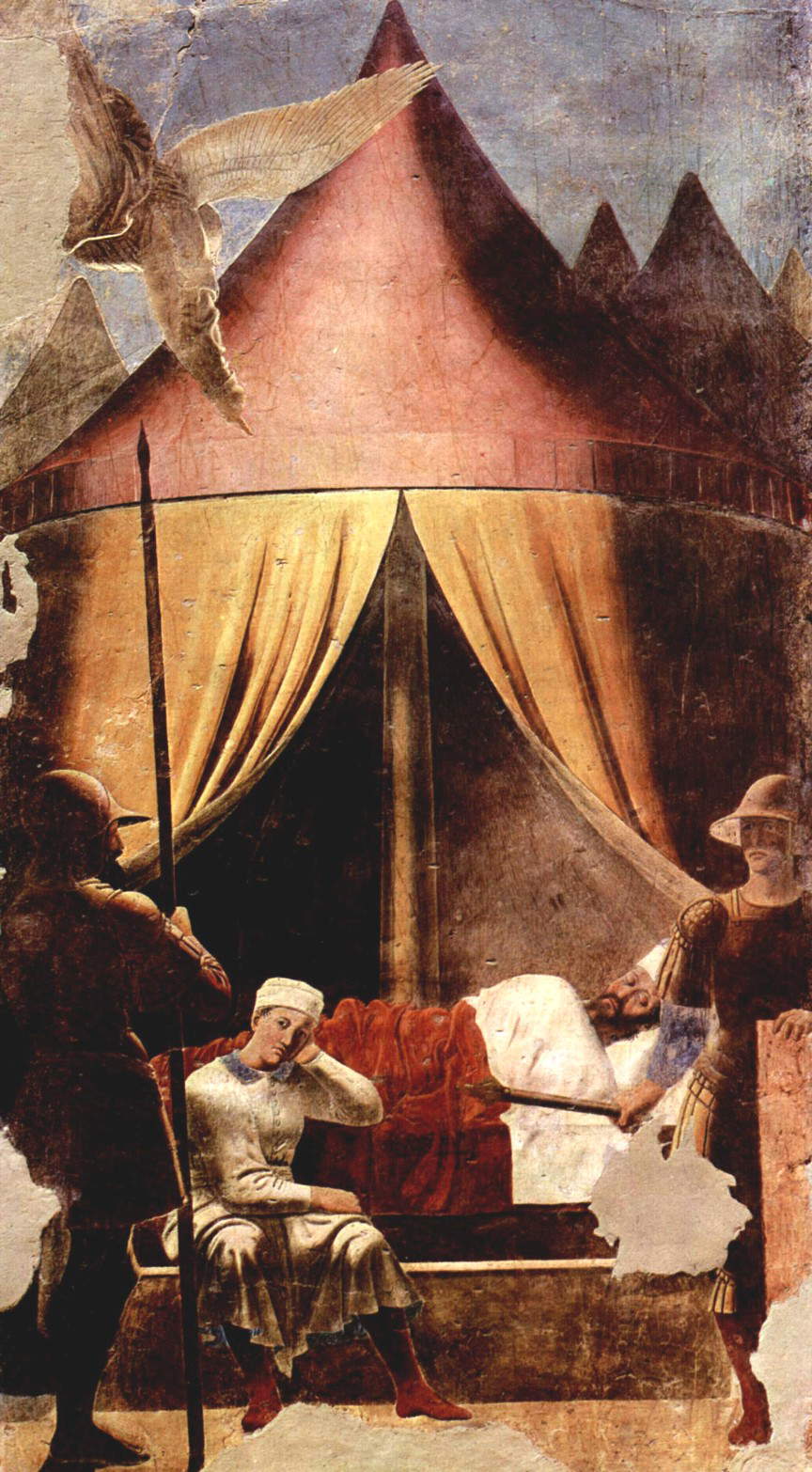

Over the centuries, the Madonna del Parto has become almost a symbol of motherhood itself, an allegory ofmotherhood, an image of devotion for mothers in every corner of the world. The Virgin is at the center, splendid, stern and sweet at the same time, young and yet already aware of her role, elegant, sober, taller than the two angels accompanying her, and therefore still painted according to the hierarchical proportions of medieval art, and yet so believable. She is depicted in a long blue dress that covers her entire body, yet highlights the realistic roundness of her belly, which she caresses with her right hand (her left hand, however, is resting on her hip). The face is fresh, adolescent, the complexion ebony, the eyes slightly almond-shaped. She stands inside a pavilion lined with vaio skins: this canopy is similar to the one painted by Piero della Francesca in the scene of Constantine’s Dream that we see in the frescoes of the Legend of the True Cross that decorate the Bacci Chapel in the church of San Francesco in Arezzo. Two angels, one with a green robe and purplish wings, the other with a robe and wings of colors reversed from their companion standing to the left of us looking on, are unhinging, in a symmetrical position and looking toward the viewer to catch his attention and urge him to look to the center, the precious curtain of brocaded fabric as if to show the mother of God. An almost domestic whiff pervades this depiction: there is a sense of intimacy, one almost has the feeling of being before a close, familiar image.

According to art historian Antonio Paolucci, Piero della Francesca, with the depiction of his pregnant Virgin, wanted to translate into images the verse of theAve Maria “You are blessed among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb.” And again Paolucci suggested a parallel (in the same way as in the film The First Night of Stillness, where again the juxtaposition is entrusted to the words of Alain Delon) with the invocation to the Virgin that can be read in Canto XXXIII of Dante Alighieri’s Paradiso : “Virgin mother, daughter of thy son, / humble and high more than creature, / fixed term of eternal counsel; / thou art she who so ennobled human nature / that her factor / did not disdain to make himself her workmanship.” In turn, perhaps, Piero di Francesca may also have inspired his fellow artists: for example, a tabernacle by Andrea della Robbia is preserved in the Cathedral of Sansepolcro where we see two angels who, like Piero’s, are opening a curtain. As for the possible derivation of the iconography of the Madonna of Childbirth, according to the distinguished art historian Irving Lavin it could be the development of the Greek iconography of the Platytera (literally “the widest”), according to which the Child Jesus was depicted inside the body of the Virgin, surrounded by a mandorla. The tradition of the Platytera would have, Lavin writes, “a quite particular development in Florence and Tuscany in the 14th century, when a new iconic type later known as the Madonna del Parto emerged. The most famous example is undoubtedly that of Piero della Francesca, the culminating moment of this tradition, but there are numerous earlier exemplars, most of them fourteenth-century and all from the Florentine or Tuscan sphere.” Lavin provides a possible explanation of the meaning of this depiction: “It should be emphasized that while the Madonna del Parto was, of course, primarily a Marian image, its underlying meaning referred to the birth of Christ from a virgin, as is evident from the examples in which Mary points toward the sash she wears around her waist, the symbol of her chastity.”

For popular devotion, however, the meaning must have been even different: Piero della Francesca’s Madonna had almost what we might call an apotropaic value. It is after all established that for the mothers of the Valtiberina the Madonna del Parto represented, for generations, a kind of icon to be venerated. The art historian Piero Bianconi even reported that, in 1954, when the idea of lending the work for an exhibition in Florence was aired, the then mayor of Monterchi allegedly refused because the local population, should something bad happen to a pregnant woman in the village during the work’s absence, would react in a not exactly positive way. If in the 1950s this cult was still so strong, as the anecdote testifies, less resistance was encountered some thirty years later, when in 1983 the municipal administration of Monterchi decided to send the fresco to the Metropolitan Museum in New York. On that occasion, the most vibrant protests were those of art historians: Cesare Brandi, for example, accused local administrators of “odious mercantilism,” since the loan was meant to obtain resources to improve the painting’s exhibition conditions. The work later did not leave: it was determined that Our Lady of Childbirth was too fragile to face such a long and treacherous transfer.

In any case, this cult of the Virgin as the patroness of women in childbirth, according to art historian Ronald W. Lightbown, has reasons that can be explained on the basis of both theology and popular belief: the Virgin, in fact, would have felt no discomfort during her miraculous pregnancy and gave birth to Christ without pain. According to St. Bernard of Clairvaux, therein also lies the glory of the Virgin: to have been “fertile without sin, pregnant without heaviness, and giving birth without pain.” These doctrines, Lightbown explains, “were certainly preached thoroughly both to the simple and the wise by a Church for whom the Incarnation was one of the two principal mysteries of the Christian religion, and Mary a figure to be glorified only slightly less than Christ.”, so that “the doctrine of Mary’s painless pregnancy and childbirth made her a natural protector for medieval women, anxious for heavenly assistance in days when childbirth was often dangerous or fatal, and labor dangerous and prolonged. As the mother of God, having herself become pregnant and given birth, she, in her mercy, could have given help and comfort to a human mother. And indeed the emphasis in Piero’s fresco is on the Virgin Mother, dressed as the women of Monterchi could see any pregnant woman in the village, and her realism must have entered their imaginations, then as it did in 1954, when they resisted her relocation for an exhibition.”

Today this devotion, though still present, has greatly faded from what it must have been like in ancient times. And we know that it was the object of veneration precisely from ancient documents: in fact, as early as the 16th century there was mention of offerings to the “Madonna of Momentana.” Simon Altmann, in a 2019 article, thought of possible forms of syncretism, since in the past the hill on which the Momentana church stood was known as Montione, a contraction of the Latin expression Mons Iunionis, or “Monte di Giunone,” hypothesizing the survival even at the time of Piero della Francesca of ancient rites related to motherhood that blended pagan elements traceable to the goddess Juno, in ancient times associated with fertility, and Christian elements. Whatever the origin of this devotion, one can go back to the aforementioned Ingeborg Walter to get an idea, however, of the meaning that the Madonna del Parto must have had for the local girls: “the representation [...] allowed women, thanks to the clear reference to their reality, to identify with the mother of God in a situation filled with uncertainty and danger for them. The pregnant Madonna was equal to them, and only as a result of the act of salvation intended for her by God was she elevated above earthly women, but this gave her the power to sustain them.” According to the scholar, the cult would have been imposed by the power of suggestion alone, for it is true that, as a local woman once told her, depictions of the Virgin are found everywhere, but less frequent are images of the pregnant Madonna, and a pregnant girl who sees before her the image of a woman equal to her ends up identifying herself more strongly with that figure. She can almost sense that the Madonna understands her, that she is truly close to her, physically close.

Piero della Francesca’s Madonna del Parto is not, however, as one might expect, the only known depiction of the Virgin incita: several even earlier iconographic examples are known, such as the Madonna di Nardo di Cione preserved in the Bandini Museum in Fiesole, the Madonna del Magnificat by Bernardo Daddi found in the Museo del Duomo in Florence, the 14th-century Madonna del Parto in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Prato (it is the work of an artist of the Giotto school and is one of the oldest examples of this iconography), the one by Taddeo Gaddi in the church of San Francesco di Paola in Florence, and also two sculptures preserved a very short distance from Monterchi, in Anghiari: one is the wooden Madonna attributed to Tino di Camaino, kept in the Abbey of San Bartolomeo, and the other is Jacopo della Quercia ’s Madonna found in the Museum of Palazzo Taglieschi. Art historian Alessandro Parronchi noted that in ancient times, it was possible to remove the figure of the Child from these two statues, which probably happened on December 18, the feast day of the expectatio Partus Beatae Mariae Virginis, the feast of the Blessed Mother established as early as the year 656, during the Council of Toledo (although it only entered the Roman calendar, the Church’s official liturgical calendar, in modern times). Could Piero della Francesca have painted Our Lady of Childbirth to celebrate this feast? We do not know. Nor can it be ruled out that the work has a political significance, since, as we have seen, the image of the pregnant Virgin was widespread in Florence and its immediate surroundings: it was typical of the time that, in territories conquered by a power, iconographic subjects typical of the conquerors’ areas of origin were spread. In this way, too, the taking possession of a village or town was signaled(on these pages we have seen this, for example, with the Majesty of Pietro Lorenzetti, from Siena, painted for Massa Marittima). Monterchi, after all, became part of the Florentine territories after 1440 and the Battle of Anghiari. Mario Salmi suggested that Piero della Francesca may have painted this image in memory of his mother, whose family was originally from Monterchi, and who had passed away on November 6, 1459. But we still don’t know anything for sure.

What then do we know for sure about this work? Piero della Francesca had painted the work for the church of Santa Maria di Momentana, also known as Santa Maria in Silvis, a small country church on the slopes of the hill on which Monterchi is located, the existence of which has been known since the 13th century. The artist painted the work on top of a 14th-century fresco by an unknown local artist depicting a Madonna and Child: we became aware of its presence in 1911, when restorer Domenico Fiscali carried out the detachment of Piero della Francesca’s work, ordered by the then Royal Superintendency of Monuments, for conservation reasons. We do not know who the client was since we do not know, nor do we know the dating of the work: the various hypotheses oscillate on a rather wide range, between 1450 and 1465. We do not have much information about the painting’s early history, but we do have a larger body of news about what happened to the Madonna del Parto from the late eighteenth century onward: in 1785, in fact, the municipality of Monterchi decided that the town’s new cemetery should be built right where the church of Santa Maria in Silvis stood. The small house of worship was largely demolished: a portion, corresponding to about a third of the building, was saved and turned into a funeral chapel. Our Lady of Childbirth, which survived the demolition, was moved to a niche above the chapel’s high altar.

In 1789 an earthquake struck the Valtiberina, but the Madonna del Par to managed to survive this time as well. Another earthquake hit the area in 1917: again, the work managed to escape, and was given for some time in the custody of the Mariani family, local residents. Then in 1919 it was moved to the Sansepolcro Picture Gallery, only to be moved again, in 1922, to the chapel of the Monterchi cemetery. Singular what happened to the work during World War II: the Italian authorities wanted to save the precious painting, to prevent it from crumbling under the bombings or being looted by the Germans. Two personalities such as Mario Salmi, a great art historian who was then a lecturer at the University of Florence, and Ugo Procacci, who worked at the Florentine Galleries, were then sent to make the necessary investigations: Piero Calamandrei recounts that they were mistaken for Germans in disguise and were repelled by the angry population, intent on not depriving themselves for any reason of the work to which they were so devoted. In 1950 the work underwent a conservative intervention carried out by Dino Dini, after which, between 1955 and 1956, the chapel was restored, with also a change in its original orientation (the entrance dating back to the 18th century was closed, and a new one opened on the southern side: the Madonna del Parto was moved from the eastern wall, on which it stood, to the northern one). Finally, in 1992 (the year of the fifth centenary of Piero della Francesca’s death, a time during which the work underwent a restoration by Guido Botticelli), for conservation reasons, it was moved to the current Museo Civico dedicated to her, which has since become the home of the Madonna del Parto: this is the former middle school of the town, which was used as a museum suitable to house the precious masterpiece. The most recent milestone in this story is the equipping in December 2021 of a new lighting system provided by iGuzzini Illuminazione, which has significantly improved the work’s legibility.

Today, we no longer see the painting as it must have appeared in ancient times. There are heavy losses on all four sides (suffice it to say that today it is two and a half meters high, and since the church was originally 5 meters high, we can imagine that it occupied a space at least 4 meters high), and some of what has survived has been restored or repainted. Probably originally, as is conceivable by looking at the technical analysis, the Virgin had a veil behind her head. “Some elements of the fresco, such as the relationship between the paved floor and the back wall,” Lightbown wrote, “will now always remain ambiguous. The probability is that the floor rose slightly in perspective, and that its lost orthogonals met at a fairly low vanishing point at eye level. But considering the damaged state of the edges and background of the fresco, all these restorations must be conjectural.”

Yet despite these conditions, very high is the fascination that this work still manages to give off, and still we can imagine that there are believers who go to venerate it. And to perpetuate this devotion, the Municipality of Monterchi has established from the beginning free admission to the Museo Civico della Madonna del Parto for expectant mothers. This renews a tradition that for centuries has linked one of the Renaissance masterpieces to the inhabitants of the village in which it is located.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.