Picasso and Rousseau, November 1908: a memorable dinner

Honneur à Rousseau. Honor to Rousseau. The banner hangs on the top floor of the Bateau-Lavoir, the Montmartre building in which Pablo Picasso set up his studio some time ago. All around are streamers and flags, and in the center of the room a table obtained from a long wooden board resting on a row of painter’s easels, and set with tablecloth, plates, cutlery and glasses rented from the nearby Azon restaurant. All the furniture has been removed from the studio, and the adjoining apartment of painter Jacques Vaillant (later to be given to Juan Gris) has been transformed, for the occasion, into the wardrobe reserved for the party guests. It is an evening at the end of November 1908: Picasso has decided to organize a banquet to celebrate Henri Rousseau (Laval, 1844 - Paris, 1910), the “Doganiere” known in the Paris of the time for his paintings as exotic as they were naïve, but capable of achieving a spontaneous primitivism that the great avant-gardists of the early twentieth century admired and, perhaps, somewhat envied. The party in honor of Rousseau will go down in history.

Guests gradually begin to arrive. There are about 30 in all. There is Georges Braque, father of cubism along with Picasso. There is Maurice de Vlaminck, leading exponent of the Fauves group. There are Picasso’s two great patrons, siblings Gertrude and Leo Stein. There is Picasso’s muse as well as lover, Fernande Olivier. There is the American writer Alice Babette Toklas. There is the painter Marie Laurencin. There is a handful of poets among whom the names Max Jacob and André Salmon stand out. Most of the guests gather before dinner at the Fauvet bar for an aperitif. While most are intent on sipping their drinks, Fernande Olivier arrives, agitated and on a rampage: chef Felix Potin has not delivered the dinner that was ordered. The cause is an unspecified mix-up: perhaps, she and Picasso miscommunicated the date of the party, perhaps the chef forgot, and the fact remains that Potin’s caterer needs to be called as soon as possible to tell them to arrange something. Only when a working phone is finally found, Potin has already closed its doors. Fernande will thus find herself cooking paella for all the guests. In Max Jacob’s studio, which becomes a makeshift kitchen.

The group moves from Café Fauvet to Picasso’s studio. But the guest of honor is still missing! In fact, the Spanish painter has decided to have him arrive last, accompanied by the real star of the evening: the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. Dinner has yet to begin and Marie Laurencin is already drunk and begins to offer entertainment. Fernande takes her back: by the time Rousseau arrives, everyone should be seated in a composed manner to celebrate the artist. And the Doganiere does indeed arrive on time, escorted by Apollinaire: all the guests stand and applaud his triumphant entrance. The very strange couple who arrived last in Bateau-Lavoir’s studio already foreshadow how the evening will go: Rousseau is a small, canny, shy little man in his late seventies. Apollinaire, on the other hand, is a buoyant forty-something, fashionably dressed, well-groomed in appearance, exuberant often to the point of excess. Rousseau is made to sit at the head of the table, seated in an elegant armchair, in front of one of his paintings, which Picasso had purchased some time earlier in a gallery for the paltry sum of five francs, a price probably barely worth the material with which it was produced: it is the Portrait of a Woman, and Picasso jealously guarded it, so much so that it is still part of the collection of the Musée Picasso in Paris. Rousseau had painted it in 1895.

|

| Henri Rousseau, Portrait of a Woman (c. 1895; oil on canvas, 160.5 x 105.5 cm; Paris, Musée Picasso) |

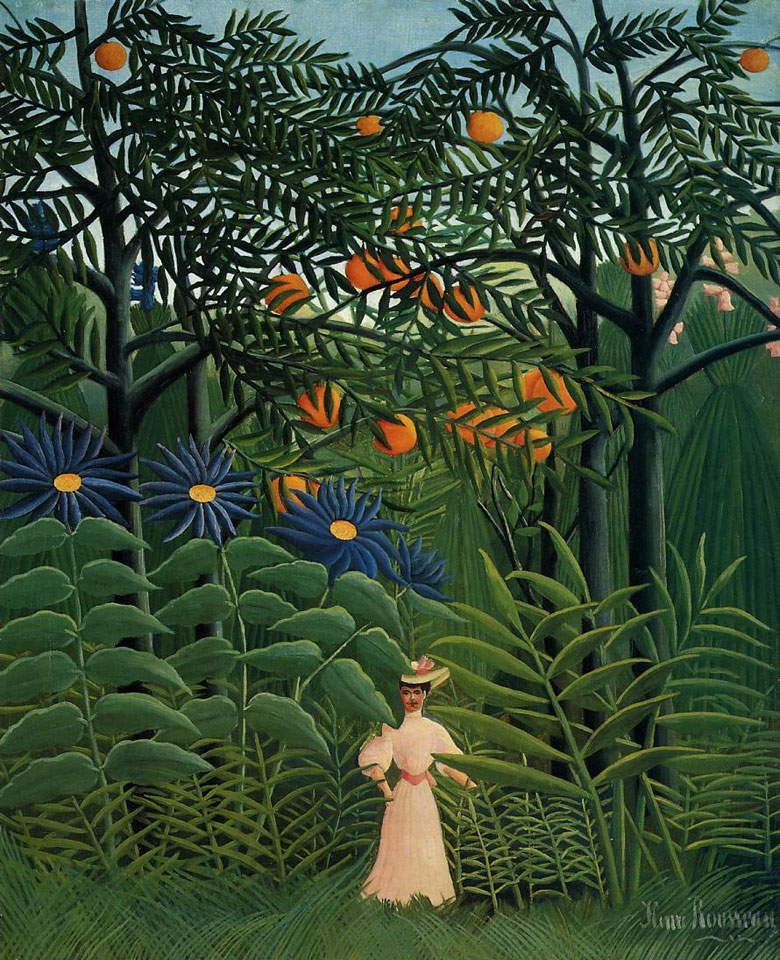

Apparently this is a rather unremarkable painting. The protagonist is a sullen lady, wearing a long, sober, extremely chastened black dress. The gaze is cold, the proportions are unrealistic, the drawing practically absent, just as completely absent is the sense of depth, because Rousseau is unschooled: he is a Sunday painter, a man who by trade is a clerk at the Paris customs office (hence the ironic nickname “the Customs Officer”) and who in his spare time dabbles with paints and brushes as he can, without great pretension, creating simple, naive images. Like this severe woman, who with her left hand leans on a twig evidently just pruned from a plant, and with her right hand holds a flower. That Rousseau had no training is evident from some of the details: from the feet sticking out from under her dress, rendered without the slightest study of perspective, from the bird flying in the sky (and it is not clear where: Rousseau’s intent was perhaps to paint it in the distance, but it seems to be fluttering near the protagonist’s head), from the crooked terrace railing. Still, that portrait exerts on Picasso a fascination experienced few other times. “It is one of the truest French psychological portraits there is,” had judged the Spanish painter, who had found in Rousseau a genuine strength, an ability to pull art out from within of which none of the avant-gardists had full command (because they had all studied, and consequently their art was affected by their studies and formative experiences, and was unable to shake it off), an expressiveimmediacy and exceptional spontaneity that made Rousseau similar to the primitive artists, a visionariness that enabled him to translate onto canvas innocent but rich fantasies of tangled jungles, exotic animals, distant peoples, and dreamed fairy tales. And in the eyes of a group of artists trying to understand the secrets of painting like primitives, a true artist with a vivid imagination like Rousseau must have appeared not only a case to be studied, but also a model to be followed. And to be taken very seriously.

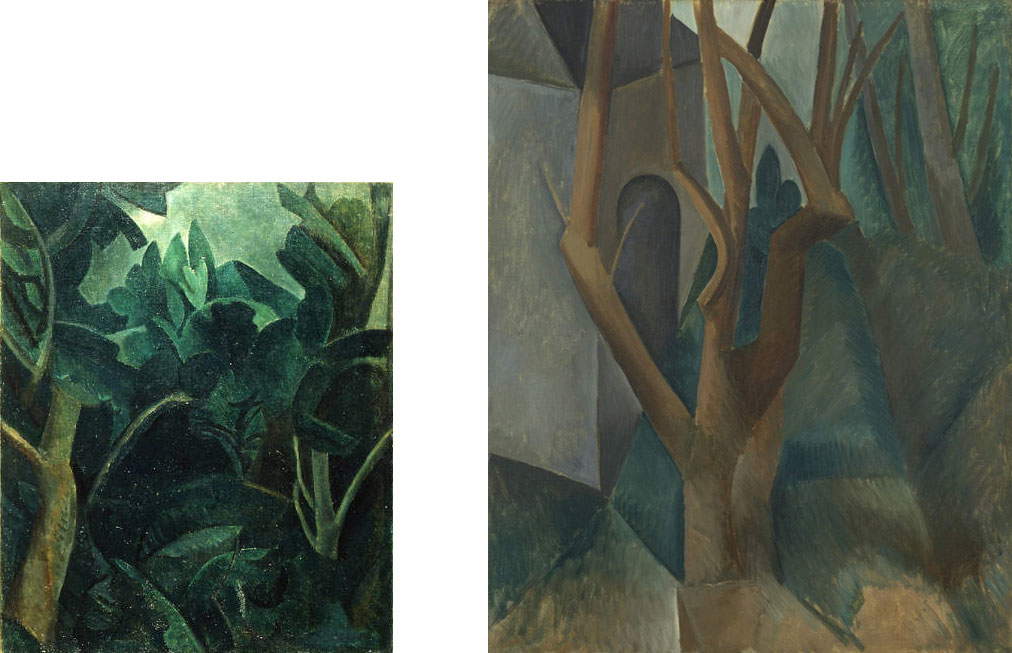

So seriously that Picasso’s own painting had begun to feel the influence of Rousseau’s. In the summer of that same 1908, Picasso and Fernande had stayed for some time in La Rue-des-Bois, a small village in the Oise department, a few dozen kilometers from Paris. It was a small cluster of houses a short distance from the town of Verneuil-en-Halatte and on the edge of a lush forest, now a regional nature park. Picasso had decided to paint the woods around the village: one of those canvases is now in Milan, at the Museo del Novecento. If we look at them (and if we look at the one in Milan in particular) we immediately notice something familiar. Picasso’s forest appears to us as a close relative of Rousseau’s jungles. The way in which Picasso operates his own simplification of the shapes of the trees and their foliage, the gradations of green used for the leaves, and the apparent banality of the composition are all features that seem precisely borrowed from Rousseau’s art. The landscapes painted at La Rue-des-Bois, William Rubin, art historian as well as director of the painting and sculpture department at MoMA, would say in the 1970s, “seem to mitigate the sophistication of Cézanne’s art with the simplicity of Rousseau’s.”

|

| Left: Pablo Picasso, La Rue-des-Bois (1908; oil on canvas, 71 x 58 cm; Milan, Museo del Novecento). Right: Pablo Picasso, La Rue-des-Bois (1908; oil on canvas, 100.8 x 81.3 cm; New York, MoMA) |

|

| Henri Rousseau, Woman Walking in the Forest (1905; oil on canvas, 99.9 x 80.7 cm; Lower Merion, Barnes Foundation) |

In short: Henri Rousseau had truly earned his place of honor at the November 1908 banquet. A banquet that, after his arrival, continued in a big way. It is true: the dinner was intended as a kind of big joke on him, but the artists who attend take it at the same time very seriously, understanding it not only as a joke but also as a way of acknowledging a tribute to an artist who had directed their research in a certain way. Rousseau, however, is interested in enjoying the moment and the company of the most up-to-date artists in Paris. Apollinaire opens the evening with a poem in alternating rhymed endecasyllables, written especially for the event and which, always poised between the serious and the facetious, goes like this: Nous sommes réunis pour célébrer ta gloire / Ces vins qu’en ton honneur nous verse Picasso / Buvons-les donc, puisque c’est l’heure de les boire / En criant tous en choeur: Vive Rousseau! / Peintre glorieux de l’alme Republique / Ton nom est le drapeau des fiers Indépendants / Et dans le marbre blanc, issu du Péntelique / On sculptera ta face, orgueil de notre temps (“We are gathered to celebrate your glory / These wines that Picasso pours in your honor / Let us drink them therefore, for it is time to drink them / Shouting all in chorus: viva Rousseau! / Glorious painter of the alma Republic / Your name is the flag of the proud independents / And in the white marble of Mount Pentelico / Your face will be carved, pride of our times.”). The rest of the dinner was handed down to us by some of those present, for example by Alice Toklas, in her Autobiography actually written by Gertrude Stein.

Apollinaire recites his poem several times. All present join in the chorus “Vive Rousseau!” Salmon begins to talk about travel and literature, but he drinks so much that he eventually gets a bad hangover and wants to get into a fight with the other diners, who try to keep him down (and eventually, unable to calm him down, lock him in Vaillant’s study). Braque makes his contribution by rescuing a bumped statue in the most excited stages of Salmon’s drunkenness. Leo Stein, on the other hand, takes care to prevent Salmon from damaging the violin that Rousseau had brought with him: on several occasions during dinner, the painter had pulled it out to play some melodies, accompanied by the other guests intent on singing and cheering him on. Rousseau himself raised his elbow more than he should have and began to tell of his improbable adventures in Mexico, fantasizing that he had participated in the French expedition in support of Maximilian of Habsburg and had drawn inspiration for his exotic paintings. Apollinaire seizes the opportunity to utter verses on the subject: Tu te souviens, Rousseau, du paysage aztèque / Des forêts où poussaient la mangue et l’ananas / Des singes répandant tout le sang des pastèques / Et du blond empereur qu’on fusilla là -bas (“You remember, Rousseau, of the Aztec landscape / Of the forests where mangoes and pineapples grew / Of the monkeys that spilled all the blood of the watermelons / And of the blond emperor who was shot over there”). Rousseau obviously plays along, perhaps more from alcohol than anything else. And he is already decidedly tipsy when he confides to Picasso, “we are the two most important artists of our time: you in the Egyptian style, me in the modern style.” The problem is that Picasso is in the group of those who have remained perfectly polished or at any rate is sober enough to remember the phrase uttered by Rousseau and make it famous. The old artist drinks so much that he eventually falls asleep, and does not even notice the wax dripping from a lantern onto his head, forming him like a funny hat. The lantern then catches fire, starting a small fire that some of the guests are forced to put out. Marie Laurencin, who as mentioned had already arrived drunk at the party due to too many aperitifs at Fauvet’s, sings and dances furiously, then falters and falls onto a tray of canapés. Apollinaire (who, moreover, has a rather troubled relationship with her) takes her aside and tries to bring her back to milder ground. She does not, however, stand her ground, and Gertrude Stein decides to slap her in the face to get her through her drunkenness. Over the course of the evening, however, she recovers. The evening continues amid dancing, Rousseau occasionally waking from slumber to play the violin, poems recited by Apollinaire and the other poets present, Picasso singing, everyone having a good time.

At three o’clock in the morning, at yet another nod of drowsiness from Rousseau, he decides to take him home: he is of an age anyway, and such parties no longer hold him. Alice Toklas and the Stein brothers, having freed Salmon, offer to accompany the painter. The four therefore leave the party, while others continue until dawn the next day. On December 4, Rousseau wrote a note to Apollinaire thanking him for the evening and telling him to give his regards to Picasso (who for many years would continue to buy Rousseau’s paintings), Fernande, and any other participants he might have met. For the little customs officer, the banquet was perhaps one of the happiest moments of his life.

Reference bibliography

- Peter Reid, Picasso and Apollinaire: The Persistence of Memory, University of California Press, 2010

- Christopher Green, Philippe Büttner, Henri Rousseau, Hatje Cantz, 2010

- Christopher Green, Picasso: Architecture and Vertigo, Yale University Press, 2006

- Dominique Dupuis-Labbé, Picasso: the Sculpture, Giunti, 2002

- Ruben Charles Cordova, Primitivism and Picasso’s Early Cubism, doctoral dissertation, University of California, 1998

- John Richardson, A Life of Picasso, volume II: 1907-1917, Random House, 1996

- William Rubin (ed.), Picasso in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, exhibition catalog (New York, MoMA, Feb. 3-April 2, 1972), Museum of Modern Art, 1972

- Gertrude Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1933

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.