Picasso and Miró compared in exhibition on Spanish modernity at Palazzo Strozzi

If we were to use a verb to define the main trends inSpanish art until around the 1930s, the task would not be so arduous, because there is one verb that immediately springs to mind: decompose. Indeed, the great Paul Cézanne, who died in 1906, had paved the way, expressing a desire to bring nature back to its essential forms. Cézanne, however, did not have the time to do this himself, and pursuing his idea was a group of Spanish artists who were fascinated by his art: among them was Pablo Picasso (Malaga, 1881 - Mougins, 1973). This tendency to decompose, common to Picasso and other Spanish artists of the time, emerges prominently in the Picasso and Spanish Modernity exhibition being held in Florence, at Palazzo Strozzi, until January (it officially opens tomorrow) and which we at Finestre Sull’Arte visited today in an exclusive preview for you, our reader friends! And, by the way, at the bottom of this article you will find exclusive photos :-)

The curator of the exhibition, Eugenio Carmona, does not like labels. However, it’s hard not to think of the term cubism when we look at one of the exhibition’s load-bearing paintings, Fernande, a female portrait executed by Pablo Picasso in 1910 and coming from the collections of the Reina SofÃa Museum in Madrid (like all the others on display at the Florentine exhibition, for that matter). It is also singular that many of the most important paintings for understanding Picasso’s art depict women: because women, for Picasso, played a fundamental role. Not only in his art, but also in his private life: and perhaps we will return to this very interesting topic later. We were saying about Fernande, whose last name was Olivier: in 1910 she was 29 years old, Picasso’s contemporary. Fernande Olivier was a painter, whom Picasso met as soon as he moved to Paris in 1904: the two had a stormy relationship, made up of betrayals on both sides. In 1910 their relationship was on the verge of breaking up (the two remained together for seven years since they met): the somber hues of the painting with which Picasso depicts his beloved probably foreshadow the end of their relationship. Fernande’s face is broken down into essential shapes: rectangles, cubes, triangles. Angular shapes and forms to which, according to Picasso, all the elements of reality can be traced. Which is to be grasped in its essence: the elements are shattered, they dissolve into elementary forms, they are, indeed, decomposed. The exhibition gives us a way to observe this path, of which Fernande is one of the starting points. Intriguing is precisely the way the curator wants to lead us to reflect on Picasso’s evolution through the portraits of the women he loved, which in the Florentine exhibition are displayed in the same room, all more or less side by side. And if the dark colors of Fernande probably allude to a troubled relationship, the more cheerful ones of other portraits tell instead of happier moments, assuming that Picasso ever knew a happy love, which if there was one, was substantiated in fleeting moments.

Spanish art of the time is thus, as is well spelled out in the exhibition, an analytical art: underlying each work is a precise order. Artists such as Picasso, Juan Gris, MarÃa Blanchard, and Manuel Ãngeles Ortiz succeed in making early twentieth-century Spain the center of international artistic events. And soon to be added to these names will be another great artist, Joan Miró (Barcelona, 1893 - Palma de Mallorca, 1983), who will start precisely from the reflections of the painters of closer Cubist observance. In the exhibition we see him well with the Siurana Path, a work in which it is the landscape that is broken down into forms: if with Picasso, in the exhibition, we see the process applied to the human figure, in Miró the fragmentation into elementary forms, marked by almost pure colors, also concerns the elements of nature.

But Miró’s research goes further. Indeed, a new trend opens up in the 1920s. For, after all, breaking down an object into its essential forms, what was it but an intellectual exercise? A problem then arises: to make art still succeed in making people feel. Artists, and first Miró, need to make sure that all that cultural baggage initiated by Picasso, Braque, Gris and others, goes with the ability to evoke sensations. Let us clarify in the meantime that Picasso will get there in a different way than Miró: and the highest example of this evocative capacity in Picasso is the very famous Guernica, where tragedy, despair and heartbreak reign, which though negative are also sensations. Miró, too, remains scarred by the tragic events of war (although he remained almost inactive during the war), but his art, unlike Picasso’s, aspires to lyricism and seeks beauty. Miró set himself the goal of arousing in the viewer of his paintings, the same feelings that are aroused by poetry: and just as poetry is capable of arousing feelings by describing a concept concisely, in a few words, so must art be equally capable of achieving that result. Few signs, but ones that communicate feelings. We realize this if we look at a work bearing a title of disarming simplicity: Painting(Pintura the original title in Spanish), made by Miró in 1925. Against a blue-gray background, laid out in a coarse manner typical of Miró’s style, a bizarre figure finds its place: a kind of black thread tangles on itself a couple of times and ends up drawing a horn, with two yellow lights above it. A dreamlike atmosphere, which transports us to another dimension: it is the dimension of poetry, where just a few signs, expressed in a synthetic way, are enough to make us feel a sensation. And Miró, of the modern Spaniards, is probably the most skilled at creating such evocative painting with so few signs.

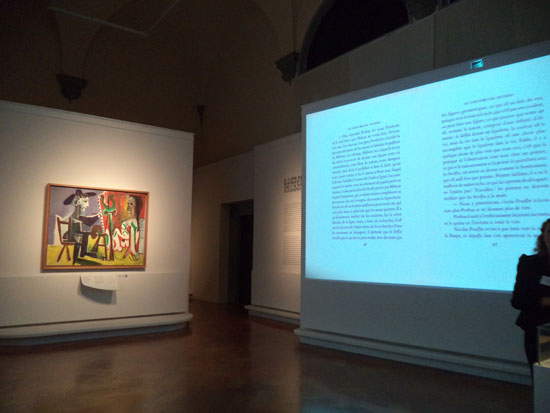

Spanish modernity would later evolve over the years: the exhibition covers a period from 1910 to 1963. We wanted to emphasize one of the themes that fascinated us most: the evolution of Cubism between the 1910s and 1930s, seen through the comparison between Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró. But the exhibition being held at Palazzo Strozzi has much to offer! We leave you with a few images we took this morning in the exhibition rooms, at which we were present in preview for the #pabloalmercato press tour organized thanks to the synergy between Mercato Centrale Firenze and Palazzo Strozzi, and we remind you that you can find all the info about the exhibition by connecting to the website www.palazzostrozzi.org.

Exclusive photographs from the exhibition Picasso and Spanish Modernity

Section 1 - References

Section 2 - Picasso: variations

Section 3 - Idea and Form

Section 4 - Lyricism. Sign and Surface

Section 5 - Reality and Superreality.

Sections 6 and 7 - Toward Guernica: the Monster and Tragedy.

Section 8 - Nature and Culture

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.