Palermo, larte at the time of war. And the stolen Caravaggio that (already) wasn't there

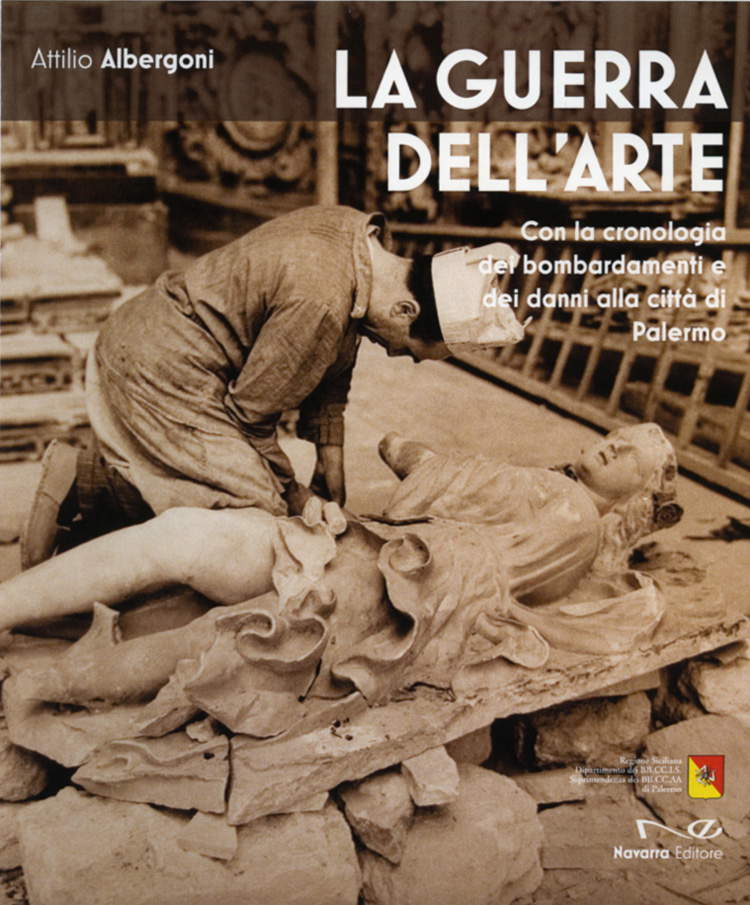

The photographic and documentary exhibition The War of Art, in Palermo at the Convent of the Real Magione, has been extended until April 8. The title, which paraphrases Sun Tzu’s The War of War, stigmatizes how works of art have always fought in order to arrive, unharmed, to the present day. As curator Attilio Albergoni writes, the photographs on display come from various foreign and domestic archives but look like images taken by one man, as if the war in Palermo was experienced by one being.

|

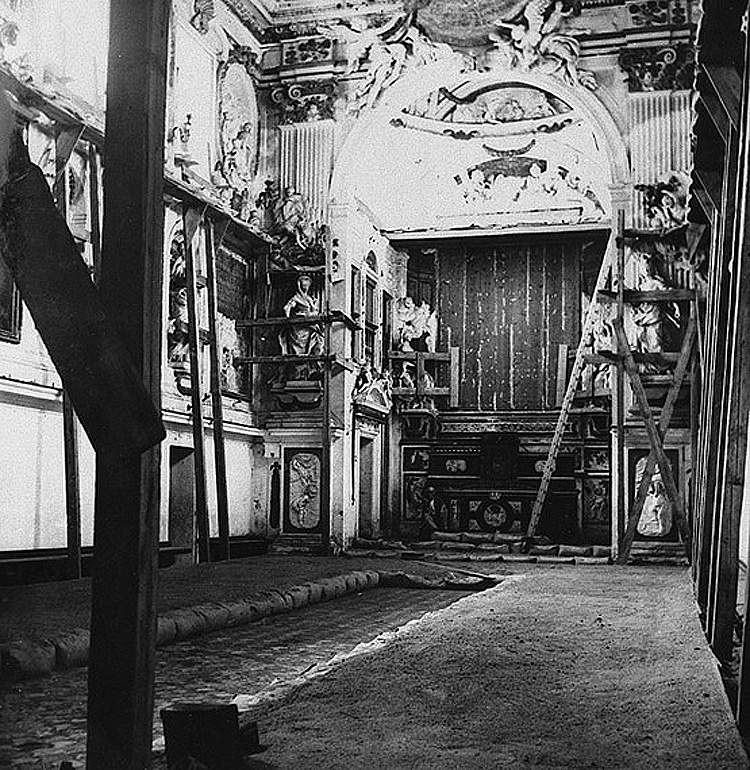

| Palermo, Oratory of the Rosary in San Domenico in Palermo, secured during World War II. |

|

| Cover of the volume The War of Art |

And it is indeed touching what is presented to the eyes of the visitor and remains imprinted in the catalog (out of print) produced by the Sicilian Region, for the types of Navarra Editore. The island capital was particularly tormented by the air raids that took place during 1943, and if the toll in terms of human lives and more generally for the city was huge, many works of art could be saved thanks to a far-sighted operation of prevention. Exemplary is the photo of the Rosary Oratory in San Domenico, where one can see the well-tested work of shoring, consolidating and securing statues and flooring through wooden planks and sandbags. The van Dyck altarpiece appears to be absent; as are other paintings, sculptures and various valuable objects from the area that were brought to a shelter most in San Martino delle Scale, on the slopes of the mountains surrounding the city.

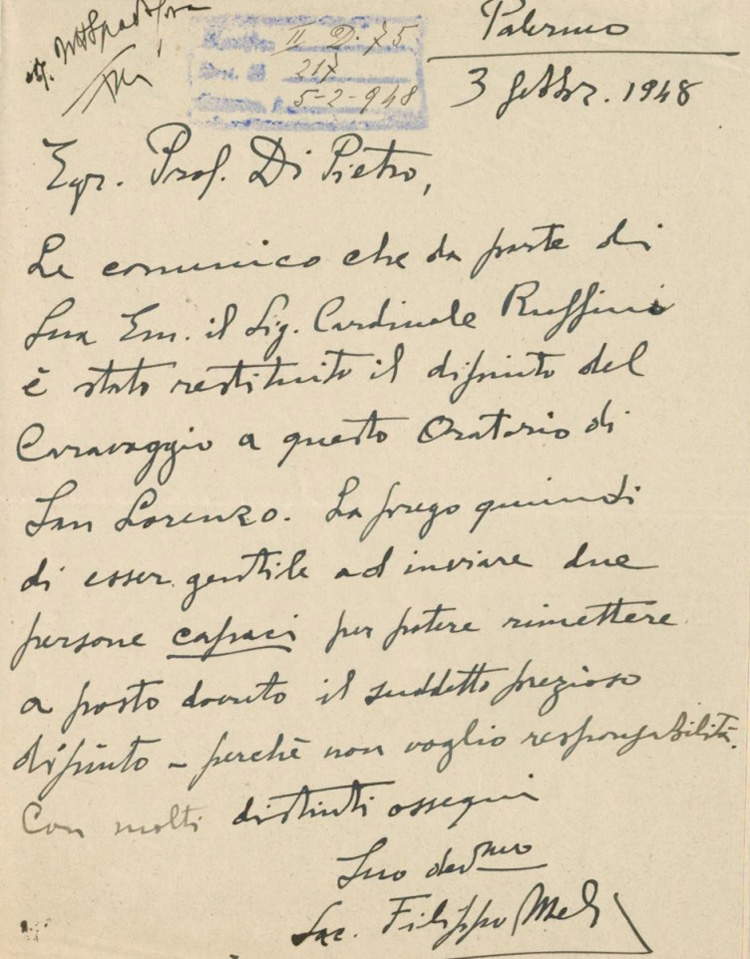

This photo brought to mind a letter consulted just a year ago, kept at the Historical Archives of the Superintendence for Cultural and Environmental Heritage of Palermo (class. II D.75, prot. 217 of 5-2-1948). Writing, to the then Superintendent of the Galleries of Sicily Filippo Di Pietro, is the rector of the San Lorenzo Oratory, Don Filippo Meli. Here are the contents:

Palermo

Feb. 3, 1948

Dear Prof. Di Pietro,

I inform you that on the part of His Eminence Mr. Cardinal Ruffini the painting of Caravaggio has been returned to this Oratory of San Lorenzo. I beg you therefore to be kind to send two capable persons to be able to put back due the said precious painting because I do not want any responsibility.

With many sincere regards

His devmo

Sac. Filippo Meli

|

| Letter dated February 3, 1948, from Don Filippo Meli to superintendent Filippo Di Pietro |

|

| Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Nativity (1600; oil on canvas, 268×197 cm; formerly Palermo, Oratory of San Lorenzo) |

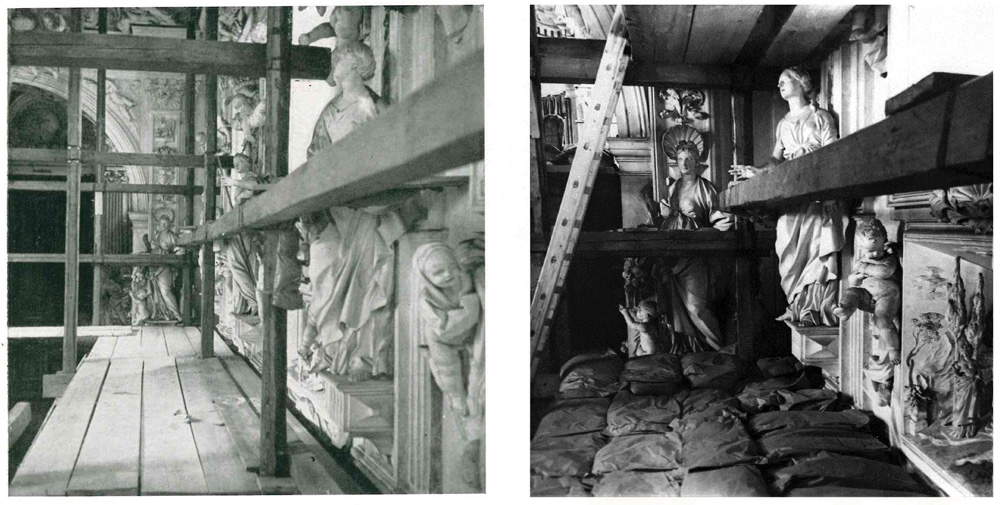

I have always wondered why the Nativity, as inferred, had been temporarily away from its usual home, where it was returning to in those early months of 1948. An exhibition? It could not have been: the painting was exhibited only in Milan in 1951 and in Paris in 1965. Here now, reconnecting the available data and delving into the subject (see La protezione del patrimonio artistico nazionale dalle offese della guerra aerea, Florence 1942, p. 339), everything becomes clearer. The canvas, during the war, was moved to a safer place and not without difficulty, related to its housing in the frame with stucco angels by Serpotta (hence, as seen, the request for capablepeople). It would then return to the site after a move to the Archbishopric once the restorations of the oratory (which suffered damage in the bombing of February 15, 1943) were completed. Restorations, which had to reckon with the long and more general reconstruction of the city center.

|

| Palermo, oratory of San Lorenzo, phases of protection of the stuccoes by Giacomo Serpotta |

|

| Palermo, oratory of San Lorenzo, entrance on Via Immacolatella after the bombing of February 15, 1943 |

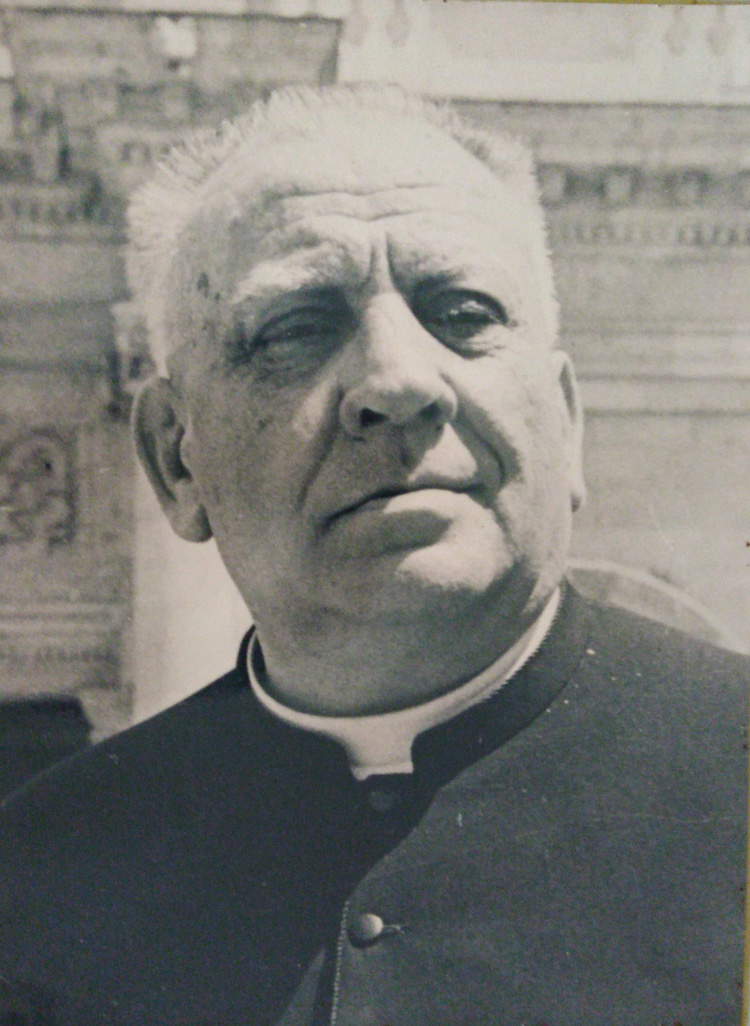

Returning to the letter, from it emerges all the care on Meli’s part for the precious painting that, as rector of San Lorenzo, found in him a jealous guardian (until his death in 1965). Meli, is also remembered as an indefatigable scholar and researcher it was he, moreover, who found the document with which Paolo Geraci undertook to paint a copy of the Nativity, identified many years later in the prefect’s office in Catania (and to which another copy is now added: it is mentioned in issue 9 of the magazine Valori Tattili).

|

| Filippo Meli (Ciminna, June 17, 1889 Palermo, August 14, 1965) |

That Meli was intimately linked to his Caravaggio whose execution in Sicily (but which, thanks to new research, we know was carried out in Rome) he sustained, also with a certain polemical flair that was ingrained in him, also appears from other correspondence preserved both in Palermo and in the Historical Archives of the Superior Institute for Conservation and Restoration (II A1, b. 31, fasc. 4). In particular, on the very occasion of the 1951 Milanese exhibition (April 21-July 15), the painting still went there dirty because the timing did not allow it to undergo restoration, which was postponed when the retrospective was closed. This operation had to proceed slowly, however, and for this reason Meli wrote several times to Superintendent Giorgio Vigni (who succeeded Di Pietro), even going so far as to address the director of the restoration institute Cesare Brandi directly. It is curious to learn in particular what he wrote to the latter on March 8, 1952, complaining that

[ ] no one has bothered to give appropriate news to this Rectory. And I, who alone (against the advice of the confreres) made the decision to send the painting to the Milan Exhibition, found myself in the unfortunate situation of not knowing how to respond to the frequent requests of the Gestors of the Company, the legitimate owners of the precious painting.

The precious painting would finally be shipped from Rome the following week, March 14.

But for a Caravaggio rescued and yet then stolen in 1969 and never recovered, World War II robbed the community of three others, lost in Berlin in 1945 as a result of the fire that broke out in the storage room where, paradoxically, they would have been secured by the museum to which they belonged, along with four hundred other paintings.

The barbarity of war, in bringing out the most execrable side of the human mind, always leaves deep and irremediable scars for all. Even una exhibition such as this one invites reflection, not without a conclusive, implicit message of hope. All is not irretrievably lost and somehow it is always possible to begin again.

For facilitating the consultation and publication of letters and photographs, we thank: Attilio Albergoni; Soprintendenza BB.CC.AA. of Palermo and in particular Evelina De Castro; Historical Archives ISCR in the person of Laura DAgostino; Maria Urso and the entire Cultural Association Genesis Ciminna; National Central Library of Rome (note the original incorrect caption for limmagine taken from La protezione del patrimonio artistico nazionale dalle offese della guerra aerea, p. 347).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.