Open window on a rediscovered Titian

The image of the suffering Christ with the crown of thorns, painted by Titian in 1547 in two identical versions, one on a slate slab given to the Habsburg emperor Charles V, now in the Prado (Fig. 1), the other a Christmas gift for his friend Pietro Aretino, containing only the variant of the reed placed in the right hand, now belonging to the Chateau de Chantilly, are considered prototypes followed at different times by some replicas generally accepted as autograph and others referable to the painter’s workshop. One of these, presented in a Christie’s auction in New York (Oct. 29, 2019, No. 772) as “Workshop of Tiziano Vecellio,” saw its initial price of $40,000 rise to the adjudication figure of more than $200,000. Freed from heavy repainting, thanks to careful cleaning and restoration, it was recently re-presented in a Sotheby’s auction (Jan. 26, 2023, No. 115)) as an autograph, partially unfinished work, referring to the great painter’s last period, being sold for over $2,000,000 (Fig.2).

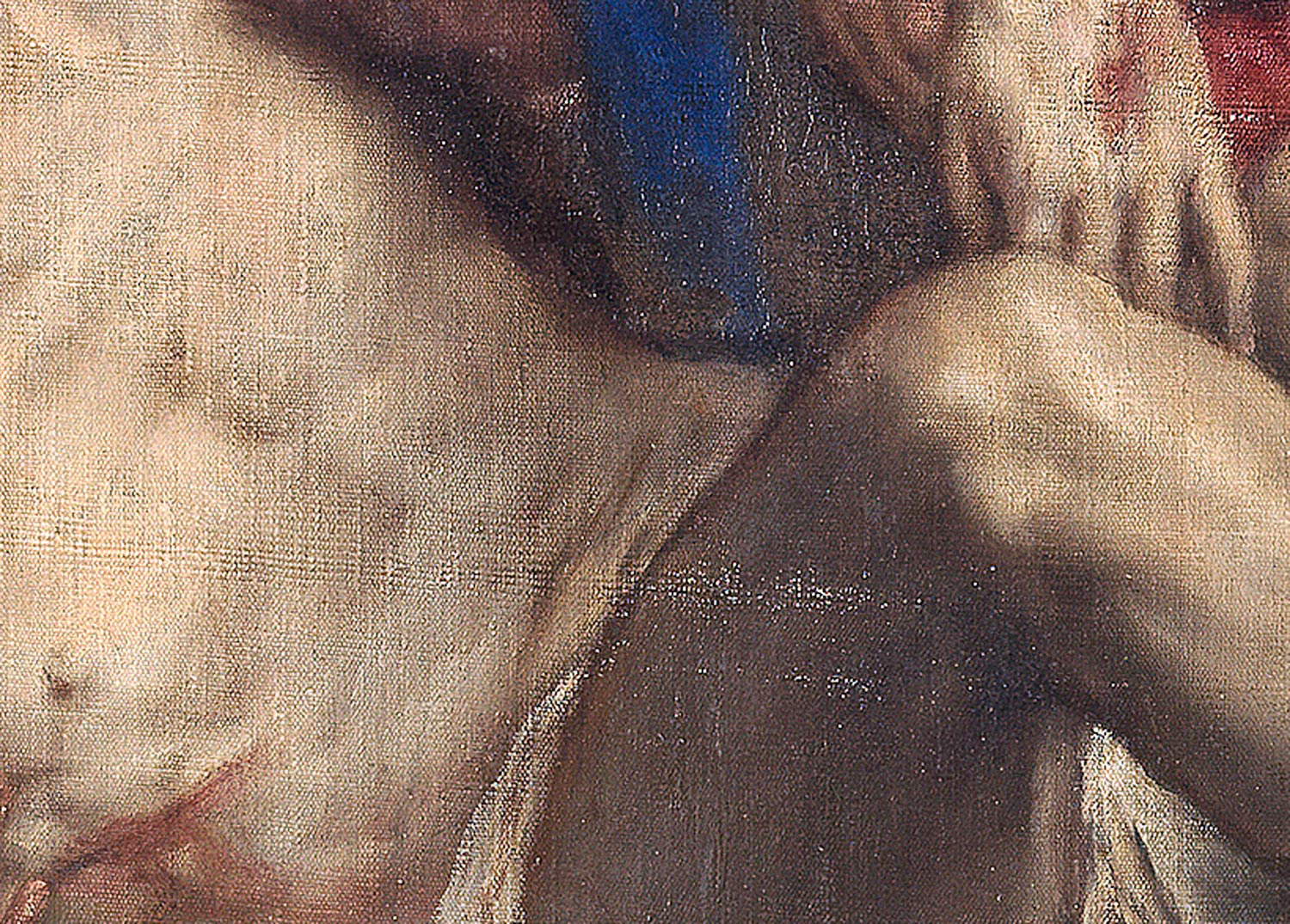

This is one of those sensational facts that happen sometimes, perhaps even more often than is commonly believed. Not yet extinguished by the echo of the event, here in fact is a new version of that mourning Christ (Fig.3), identical to the Prado prototype, half-covered by the purple mantle and crowned by the tangle of brambles that cause drops of blood to drip from his forehead down his body, but with the variant of a picturesque figure to his left, mockingly handing him the infamous reed as a scepter: an instant that precedes the iconic image belonging to the established iconographic tradition where the symbolic reed is normally depicted already in his hands.

Unlike the other versions, this new specimen depicts the passage from the gospel according to Matthew (27:20), with the handing over of the reed to Christ, as a supplement to the burlesque parody of the royal attire. This is an image that has never previously appeared in the work of any painter or even replicated later by Titian himself. A novel variation on the traditional iconographic repertoire, the novelty of which, noted by the young Van Dyck in the course of his passionate studies in Venice of the works of the beloved Cadore painter, was to serve as a model for him, upon his return to Antwerp, for variations on the same subject such as the Derision of Christ in the Princeton University Art Museum (Fig. 4) and The Crowning with Thorns in the Prado (Fig.5) .

The painting that has come to light today (oil on canvas, cm. 63.6 x 60.6) has undergone several tamperings over time. Its format, originally almost square, was altered in the 18th century, due to a custom that saw the furnishings of patrician palaces follow the change in taste dictated by the prevailing rocaille style, so that the format of the paintings also often underwent changes, to be adapted to mixtilinear or oval frames, sculpted with mainly floral motifs.

Fortunately, in adapting it to the oval format, instead of reducing it by cutting off the corners, the painting was enlarged by lining it with an enlarged canvas shaped for the purpose, prepared in the surplus parts with mestica colored with the red Armenian bole in use at that time, to fill the difference in height from the original work and equalizing its appearance with similar oil color. In the last century the work was finally further enlarged to fit a new, evidently rectangular frame, adding a second lining (Fig.6).

Fortunately, in spite of these tamperings, the pictorial film was not affected except in minimal surrounding parts, and a careful restoration and cleaning operation brought it back to its original appearance. A new lining was then applied to the work, after removing one of the two previous ones and preserving only the first one for fear of damaging, in detaching it, the original one, which is very fine and delicate, made up of a weave of linen threads so thin and adherent to each other as to leave minimal interstitial spaces, filled with a light layer of light gray mestica, lacking real thickness. One can recognize in it the unmistakable Titianesque method of working, which in the finished works lets one perceive the weave of the canvas beneath the surface of the paint film, where the crack is almost indistinguishable to the naked eye, while in some areas the underlying light presence of the preparation emerges. In this Mock Christ the evidence of this light mestica, left during the restoration operation intentionally devoid of retouching in a small abrasion of the paint film near Jesus’ elbow (Fig.7), it can be easily recognized in many of the painter’s works such as in the 1559 Burial of Christ belonging to the Prado (Fig.8), or in certain peripheral areas and only roughly covered with color, in numerous others such as the National Gallery’sAllegory of Prudence (Fig.9). In some cases the transparence of the light preparation is intentionally used by Titian to lighten the chromatic tone in a kind of sparing drafting (Fig.10).

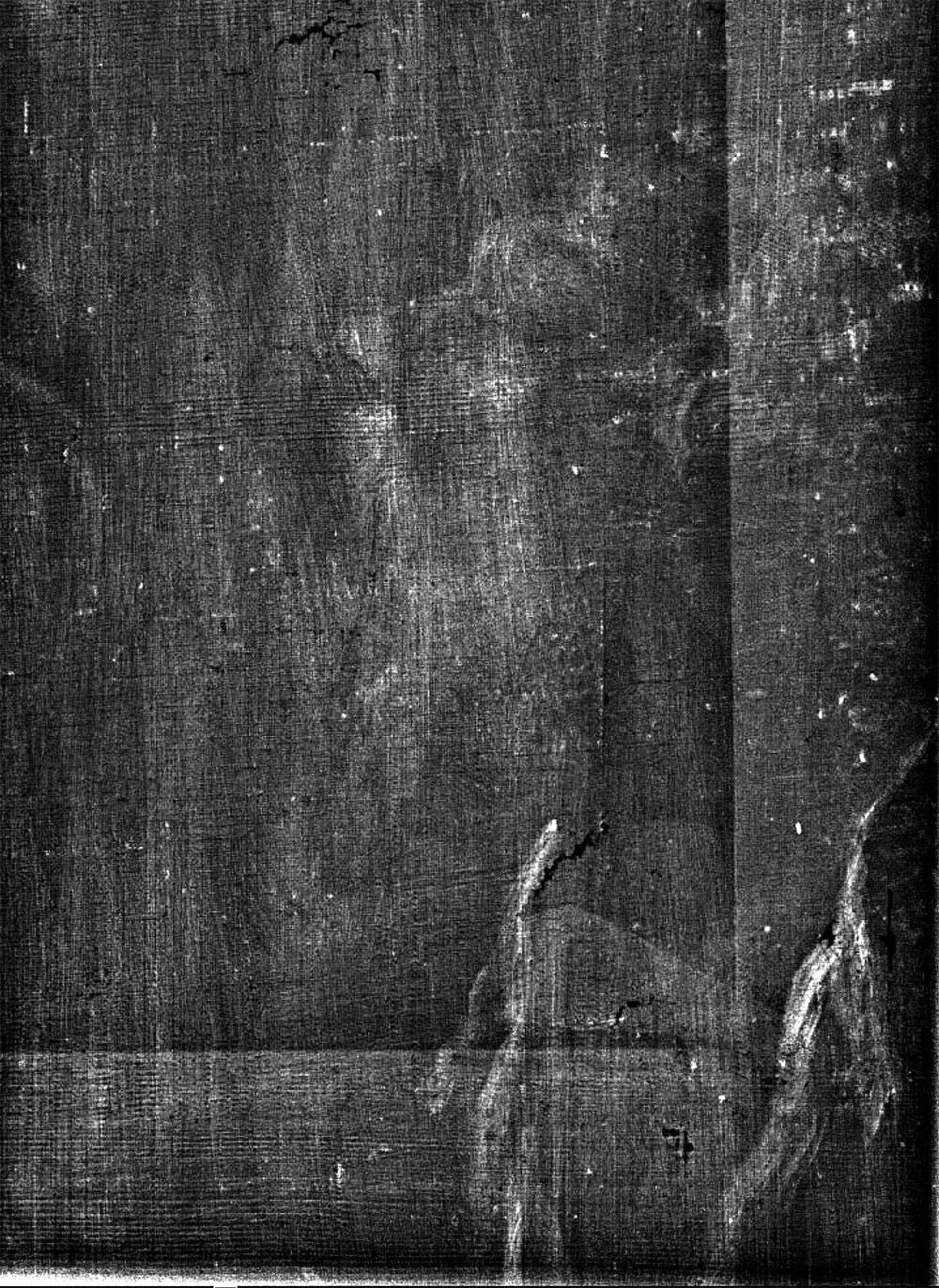

Subjected to radiography, the work revealed nothing significant in the figure of Christ, as was to be expected since it is a faithfully replicated image from a predetermined model. The only part where it is possible to detect an alien element is in the lower right corner on the torso of the old man, between the lapels of his shirt, where lines are evident that seem to conform to an edge of solid structure perhaps of some furnishing object, but apparently unrelated to the figure of the character, and therefore of undecipherable relevance (Fig. 11).

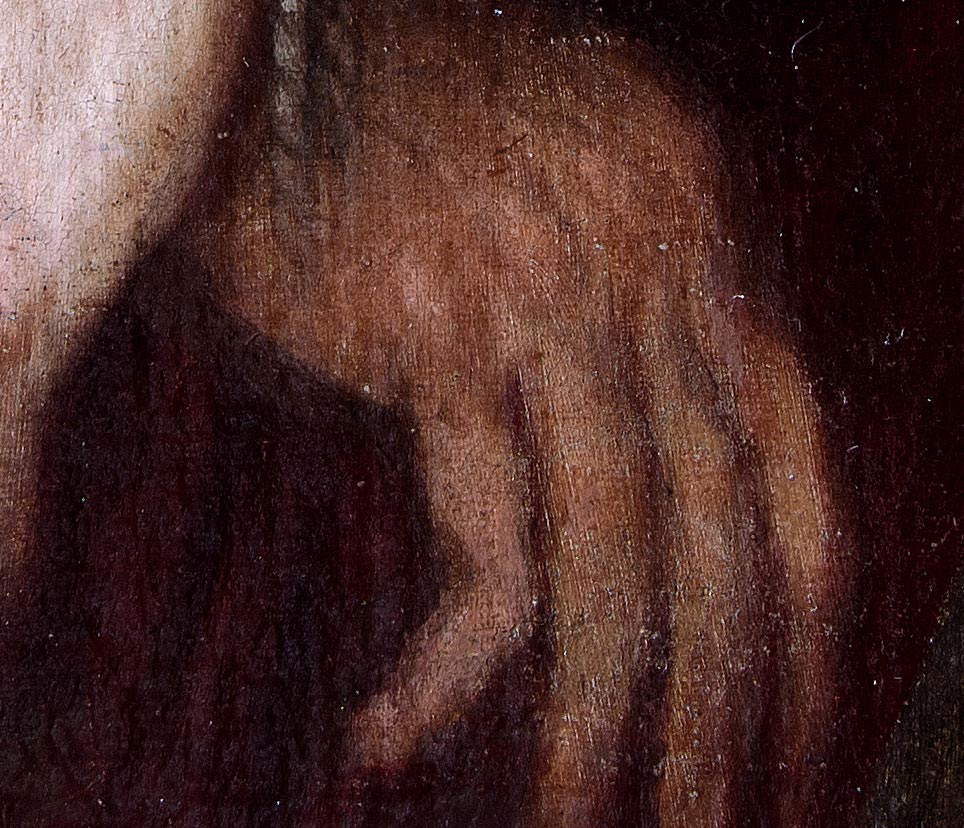

Christ’s astonishing physical prowess, modeled with crisp consistency, shoulders, arms and chest in evidence, towers over the senile frailty of his mocker, matching the expressive contrast of their gazes, insolent that of the old provocateur, vainly seeking humiliation in the half-closed eyes of his victim, blatantly heedless instead of that insignificant presence and immersed in the mournful awareness of his own fate (Fig. 12). The image of Christ, shaped by skillful chiaroscuro, achieved by repeated passages of light glazing, appears very close to the accurate pictorial texture that characterizes the two versions in the Prado and the Chateau de Chantilly, diverging markedly from the various replicas, of more essential execution, some of which have generated understandable doubts about the autograph.

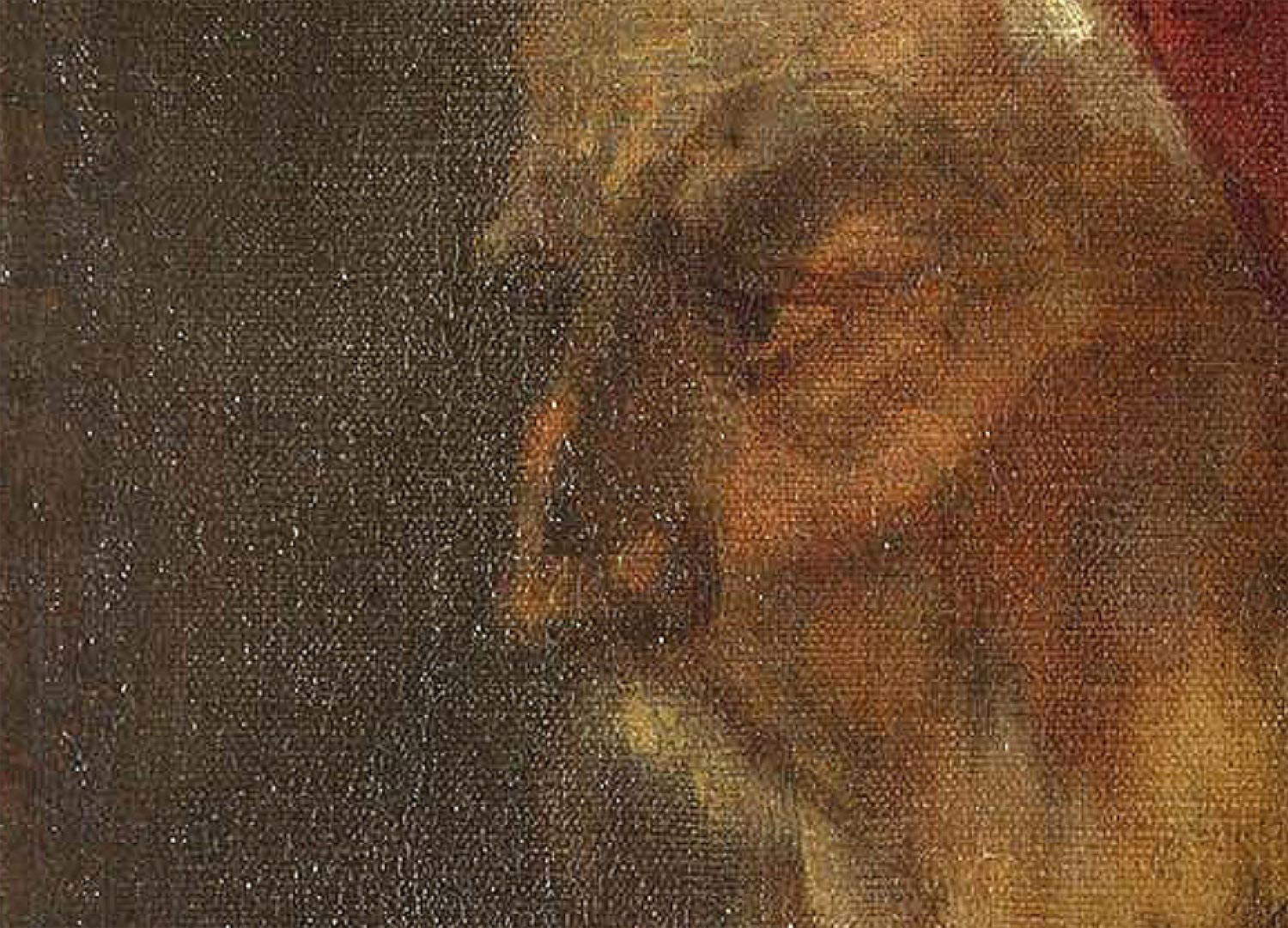

But the most significant part that confidently rules out the possible intervention of helpers is precisely the significant realism that connotes the figure of the old commoner, with his bony chest left exposed by the tattered shreds of his shirt (Fig. 13). Unlike the figure of Christ, the executive immediacy of this picturesque figure already seems to prelude, around the second half of the 1950s, the expressionistic pictorial disintegration of the painter’s last years. The form springs with great expressive force from a play of light and rough touches on the scrambled hairs of the beard, on the sparse hairs barely suggested in the curls escaped from the headdress at best socked on the nape of the neck, in the eye drained on the tentativeness of the wide-open eyelids. No one in those years could paint in this timeless way who did not have the miraculous brush of Titian Vecellio.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.