Nymphs and Venuses in the early 16th century Veneto, from Giorgione to Titian: love in all its meanings

The installation of the Uffizi rooms dedicated to the Venetian and Tuscan sixteenth century that opened in spring 2019 allows us to embrace, at a single glance, two extraordinary works placed in two different but communicating rooms, by two painters who lived in the same years (indeed: they were contemporaries), who worked in the same city, namely Venice, and who shared the hedonism that distinguished Venetian painting in the early 16th century: they are Tiziano Vecellio ’s Venus of Urbino (Pieve di Cadore, c. 1490 - Venice, 1576) and Bernardino Licinio ’s The Nude (Venice, c. 1485 - after 1549). Works both made in the same turn of the year (the Venus of Urbino is from 1538, while La nuda dates from about 1540), affected by the same atmospheres and part of the same fashion, and sharing several elements, although there are also others that separate them. The most obvious common denominator of this and other similar works, however, is a genre very much in vogue in the Venice of the time, of which Titian’s Venus is but the most famous and well-known episode: the naked, reclining young women who abound in the production of their contemporary painters.

It is necessary, however, to take a step back and return to the work that gave rise to this fortunate genre: the Sleeping Venus, a masterpiece by Giorgione (Giorgio Barbarelli?; Castelfranco Veneto, 1478 - Venice, 1510), finished by Titian himself, who is said to have repainted the landscape (while according to some scholars, he actually repainted the entire work). The first mention of this painting, which is now in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden, dates from a few years after it was made: it was seen by the man of letters Marcantonio Michiel (Venice, 1484 - 1552), in 1525, in the house of the Venetian patrician Girolamo Marcello, who in all likelihood was the commissioner of the painting. The work, however, is in Germany today because, while in 1660 it was still attested in the Marcello house, in 1697 it ended up on the market, and the French antiquarian Le Roy bought it for Augustus of Saxony: thus, in 1707, the work appeared for the first time in the inventories of the German gallery, cited as Eine Venus mit einem Amorett von Giorgione (the cupid accompanied Venus in ancient times before it was repainted, as X-rays have shown). In his Notizia d’opere di disegno, a treatise published in Bassano in 1530, Michiel described the work as “the canvas of the Venus nuda che dorme in un paese cum cupidine fo de mano de Zorzo da Castelfranco, ma lo paese e la Cupidine forono da Titiano” (it was thus Michiel who had been the first to spread the reliable news of the Cadorino’s intervention in the painting). This was a decidedly innovative work, the meaning of which has long been debated. To explore it, one can start with a hypothesis formulated by Australian art historian Jaynie Anderson, among the leading experts on Giorgione’s art: according to the scholar, the work would have been executed for the wedding between Girolamo Marcello and Morosina Pisani celebrated on October 9, 1507, and the Venus would represent the beauty that protects the Marcello family, which according to its members would have originated from the lineage of Aeneas (and moreover, as is well known, Aeneas himself was believed to be the son of Venus by mythology).

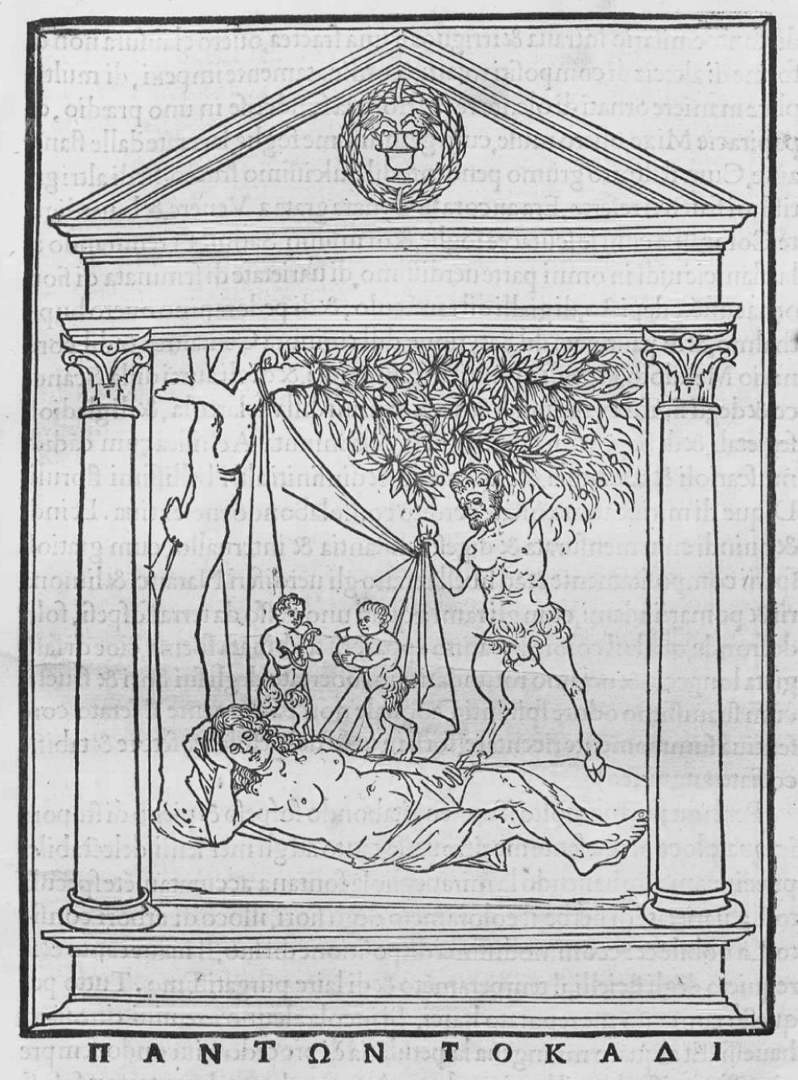

Giorgione’s novelty is interesting both iconographically and iconologically. Before the Dresden Venus, no painter had painted a deity in these terms: naked, asleep, lying on a sheet laid on a lawn, sensual to the point of eroticism (with even a hand caressing her genitals: more about this gesture later). The invention has been traced (Fritz Saxl first mentioned it in 1935) to a woodcut, attributed to Benedetto Bordone, illustrating theHypnerotomachia Poliphili, the celebrated allegorical novel printed in Venice itself, in Aldo Manuzio’s printing house, in December 1499: here, we find a classical subject, a Nymph discovered by a satyr, which would later be taken up, in all its carnality (obviously attenuated by Giorgione, who was inspired by it for mere iconographic reasons), by numerous artists from the sixteenth century onward. This peculiarity, which makes Giorgione’s Venus so physical and seductive, has been the subject of various readings. The sensuality is said to have been intended by Giorgione: to explain it, Maurizio Calvesi has quoted a passage from the Dialogues of Love, a treatise, also published by Manuzio, in 1535, by the Portuguese philosopher Judá Abravanel (Lisbon, c. 1460 - Naples, c. 1530), known in Italy as Leone Ebreo. The treatise states that painters “paint naked” the goddess Venus “because love cannot be covered, and again because she is carnal, and because lovers must be found naked.” Giorgione’s Venus is thus perfectly and fully cast in an earthly and sensory dimension (and it is for this reason, according to Calvesi, that she touches her pubis with her hand). The novelty therefore lay in the painter’s discovery of the physical beauty of women: in a 1988 study, art historian Davide Banzato, in agreeing with those who had recognized in Giorgione “the unique invention of a sexuality of images,” quoted a passage from a study on Giorgione by Eugenio Battisti and Mary Lou Krumrine, according to whom “naturalism is a highly fantastic instrument by which [...] the aesthetic appreciation of female beauty can and perhaps should lead to the physical enjoyment of it, with capacities at once stimulating and liberating.” Sensuality in relation to the generative potential of love also explains why the painting is to be placed in a marital context.

|

| Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus and Bernardino Licinio’s Nude in the halls of the Uffizi |

|

| Giorgione (finished by Titian), Sleeping Venus (1507-1510; oil on canvas, 108.5 x 175 cm; Dresden, Gemäldegalerie) |

|

| Benedetto Bordone (attributed), Scene with Nymph and Satyr, from the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499, published by Aldo Manuzio in Venice; engraving, sheet 29.5 x 22 cm) |

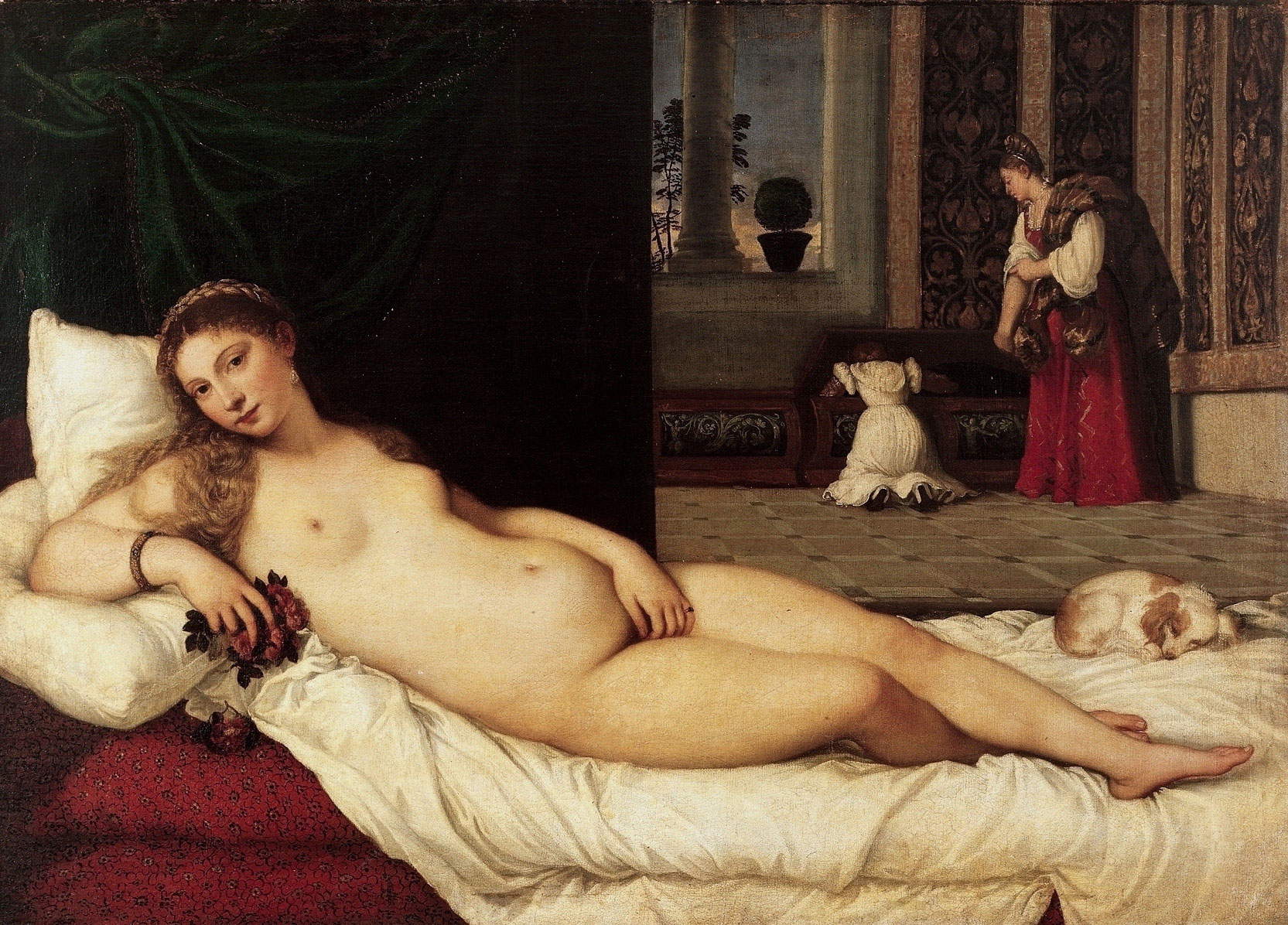

It was therefore Giorgione’s precise intention, as, moreover, Pietro Zampetti had already pointed out in the 1950s, to paint a nude for contemplation, immersed in an idyllic landscape, familiar to the commissioner, who could easily recognize in it the countryside around Asolo, a place of habitual leisure sojourns of the Venetian patriciate. After Giorgione, this genre enjoyed a vast and lasting fortune: the most celebrated of the artists who picked up its baton was Titian himself, with his Venus of Urbino painted some thirty years after the Sleeping Venus. And compared to his mentor, Titian introduced other elements that accentuated some features of the Giorgionesque revolution. Again, this is a work that was probably painted in the context of a couple’s union: indeed, we know that the work was executed in 1538 on behalf of Guidobaldo II della Rovere (Urbino, 1514 - Pesaro, 1574), duke of Urbino, who had married Giulia da Varano in 1534, and who in March 1538 had written to one of his agents in Venice, Girolamo Fantini, not to leave the lagoon city without two paintings, namely a portrait of the duke and a “nude woman,” unanimously identified as the Venus of Urbino, which was therefore about to be finished that year and transported to the Marche city (which he would later leave in 1631, heading for Florence, along with most of the Urbino collections: they were the dowry of Vittoria della Rovere, who had married Ferdinand II de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany). The first to describe it was Giorgio Vasari, who in the 1568 edition of the Lives illustrated it as “a young Venus lying, with flowers and certain thin cloths around, very beautiful and well finished.”

Venus appears wide awake to the eyes of the viewer (John Shearman, in his famous essay Art and Spectator in the Italian Renaissance, clearly writes that Titian had foreseen a spectator in the structure of the work, and that spectator would be none other than Guidobaldo della Rovere himself), in contrast to Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, and she is presented with certain attributes that clearly refer tonuptial love: the roses that the goddess holds in her right hand (a symbol of the constancy of love, as well as a flower sacred to Venus: together with the myrtle vase on the windowsill, they are the only attribute in the painting that allows identification of the goddess, since Titian removed further references to mythology), the little dog (a symbol of fidelity), the pearl earring (a symbol of purity). What’s more, the chest in which the two maids are rummaging also hints at a matrimonial bedroom (since, in the Renaissance, it was a typical bedroom piece of furniture), while the setting (a sumptuous interior with velvet curtains, with a mullioned window in the background, with precious tapestries) recalls a dwelling of the nobility of the time. This is another important difference from the Sleeping Venus, which was instead immersed in a bucolic setting: it is likely that the change of setting was due to the need to continue to ensure ease of identification for the patron (the court of Urbino did not go on vacation in the Venetian countryside, and perhaps that is why Titian opted for an interior). All these elements thus lead one to think that the meaning is not so different from that of the Sleeping Venus, and that the Venus of Urbino does not represent, as has been assumed by some, the celebration of erotic love, but rather, if anything, conjugal love, and the sensuality is to be understood as that of the wife who gives herself only to her husband. It is, however, true, as can easily be seen, that Titian accentuates the eroticism of the sleeping Venus, which there was suggested and here is instead conscious, since Titian’s goddess uncoveringly invites the viewer: it is useful here to echo Shearman, according to whom the part of the viewer of the painting is changed from Giorgione’s painting. The Venus of Urbino, is a “portrait of a nude figure horizontally directing her gaze to her lover,” an iconographic invention of Titian’s that makes an explicit invitation to the viewer: the Venus goddess thus has an awareness that Giorgione’s does not, and consequently the role of the viewer is transformed. “While Giorgione’s Venus is passively offered to our contemplation,” art historian Daniel Arasse has written, “she ’consciously’ offers herself to a contemplation that she herself accepts.” But that’s not all: “Giorgione,” Arasse continued, “had placed the nude body in a landscape and constructed mediated echoes there, subtle rhyming effects between the curves of the body and those of nature. By contrast, Titian’s Venus is seen in a palace interior, from which the world of nature is barely glimpsed through the window. By a simple change of place, Titian makes his model a woman who can be real, while Giorgione’s woman could only be perceived as a mythical character.”

As for Bernardino Licinio’s Nuda, there is meanwhile to specify that we owe today’s title to the art historian Detlev von Hadeln, who published it in 1923, attributing it for the first time to the Venetian painter, but we have no ancient attestations: it can be assumed to identify it with a “nude” that Michiel had seen in the bedroom of the Lombardian merchant Andrea Odoni, but there are no certainties about this. It is highly probable that Licinius wanted to depict an allegory of love as Giorgione and Titian had done (the two doves that appear near the naked woman could be a reference to the goddess Venus, since they are animals sacred to the goddess), but it has also been noted that what differentiates Licinius from the previous two is the attempt to eliminate any mythological aura from the subject. A woman, then, with a full, earthy and inviting physicality: it is not even to be ruled out that the woman depicted is even a courtesan. A hypothesis that, moreover, some have also formulated for the Venus of Urbino, although it is a reading that seems unreliable, given the obvious conjugal references: more likely, if anything, that the courtesan is the one painted by Licinius, and therefore embodies a less romantic love than that of the Titian goddess. A further declination of love in sixteenth-century Venice.

|

| Titian, Venus of Urbino (1538; oil on canvas, 119 x 165 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Bernardino Licinio, The Nude (c. 1540; oil on canvas, 80.5 x 154 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

The echo of Giorgionesque invention would last a long time in Venetian art. There were, meanwhile, those who took it up again to include it in larger compositions. This was the case with Giovanni Bellini, who a few years after the execution of Sleeping Venus (Venice, c. 1433 - 1516) was inspired by his younger colleague from the hinterland (the two were separated by about fifty years of age) to include a half-naked woman, lying like Sleeping Venus, in his Feast of the Gods, a 1514 work preserved at the National Gallery in Washington: she is a nymph (probably Lotide) being pursued by the god Priapus, who sneaks up on her while she is asleep. It has to be said, however, that the two characters also faithfully trace the engraving of theHypnerotomachia Poliphili, a work that Bellini surely knew, and it is therefore difficult to understand what his source was and how extensive the recourse to Giorgione might be, or in what way Giorgone might have oriented his intentions. The same can be said for Dosso Dossi (Giovanni Francesco di Niccolò Luteri; San Giovanni del Dosso?, c. 1489 - Ferrara, 1542), who adopted the same scheme in his Pan and the Nymph of c. 1524, a mythological allegory now housed in the Getty Museum in Los Angeles: here too we find a sleeping nymph, surrounded by two female figures, while Pan comes up behind them. As is typical of the adopted Ferrara painter, it is extremely difficult to reconstruct the plot of the painting: we can say, however, that Dosso, since he was well acquainted with the works of Giorgione, may have drawn from the Castelfranco painter the motif of the nude woman lying in the landscape (a landscape that, moreover, is distinctly Giorgioneesque in Dosso).

One who particularly appreciated Giorgione’s idea was Palma il Vecchio (Jacopo Negretti; Serina, c. 1480-Venice, 1528): his Nymph in a Landscape, also in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden, is but perhaps the most famous example of a group of similar works, such as the Venus in a Landscape in the Courtauld Gallery in London, which differs from the one in Dresden because, unlike the latter, she covers her pubis, or like the Venus and Cupid in a Landscape at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, a copy of the London one with the simple addition of the little god of love, or again like the Venus and Cupid at the Fitzwilliam Museum, where the very sensual goddess receives an arrow from her son (although we do not know who is passing it to whom: it is likely, however, that Palma the Elder intended here to illustrate the antecedent of the Venus and Adonis story, with the goddess mistakenly hitting herself with an arrow from Cupid and falling in love with the handsome young man). The Nymph, however, is conceptually more similar to Licinius’s work (although earlier: it can be dated to about 1518-1520) than to Giorgione’s: although, compared to Giorgione’s and Licinius’s women, Palma’s is awake and gazes into the viewer’s eyes, here all reference to the goddess of love falls away (admittedly, even in Giorgione the links were tenuous: the pose, which recalled that of the demure Venus covering her pubis, and the link to the origins of the family), and the hand is far from the genitals, a sign that this nymph, given also her attitude, would seem to be waiting for nothing more than to give herself away. Scholar Mauro Zanchi has dwelt at length on the nymph, motivating it on literary grounds, in particular calling into question Pietro Bembo ’s Asolani (Venice, 1470 - Rome, 1547), where, Zanchi writes, “women are considered as the nymphs of the woods, capable of enchanting men with a single glance and attracting them with the beauty of their naked bodies, sometimes becoming an obstacle on the winding road that leads to the attainment of moral elevation.” One could read the Nymph in this way, but the same art historian warns that, in the same production of Palma the Elder, one can also grasp opposite messages, as in the case of the Venuses, which become “synthesis of an ideal of virginal beauty,” especially as the painter would almost seem to introduce a double identification, adding to Venus some characteristics of the goddess Artemis, who is known to be a virgin (one can consider “the gesture of the left hand in an inverted V an attribute of Diana,” and one can think “that the god of love is delivering an arrow that could also be taken from the lunar goddess’ quiver.” the scissor-finger gesture often appears in the Palma nymphs). Moreover, Diana is the protagonist along with other nymphs in a painting preserved at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna: works such as those just reviewed, for Zanchi, could also contain “’proto-feminist’ messages” in that the compositions are crowded with “emancipated” women (a reading that is probably too far-reaching: not least because, while it is true that in the early sixteenth century women enjoyed a better status than they had enjoyed in earlier eras, this was true only for certain cities and, of course, for the upper echelons of society).

To the same climate belong other works, such as the so-called Venus in a Landscape by Giovanni Cariani (Fuipiano al Brembo, c. 1485-Venice, 1547), called “Venus” although there is no evidence of details that could identify her with certainty as the goddess of love, or the splendid Venus and Cupid by Lorenzo Lotto (Venice, 1480 - Loreto, 1556/1557), preserved at the Metropolitan Museum in New York and almost certainly executed, again, on the occasion of a wedding (perhaps that between two noblemen from Bergamo, Girolamo Brembati and Caterina Suardi: at the time, Bergamo was part of the Republic of Venice). Of the paintings seen so far, Lorenzo Lotto’s is the richest in symbolic references: the roses, the pearl earrings, the cornucopia (a symbol of fecundity and prosperity), the myrtle (an allusion to love), the tiara (which was typical of brides), the brazier (another reference to marriage, since it was an object that furnished the marriage chambers of the time). The lighthearted and goliardic attitude of Cupid, engaged in performing anacrobatic urination through the garland, is incredibly curious: this gesture has been read as a symbol of fertility, since the mimicry recalls penetration and subsequent ejaculation. Finally, there is one last work to be added, which brings further grounds for discussion: it is the Venus by Giulio Campagnola (Padua, 1482-after 1515), the one that is chronologically closest to Giorgione’s Venus, having been made around 1510.

|

| Giovanni Bellini, Feast of the Gods (1514; oil on canvas, 170.2 x 188 cm; Washington, National Gallery of Art) |

|

| Dosso Dossi, Pan and the Nymph (c. 1524; oil on canvas, 163.8 x 145.4 cm; Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum) |

|

| Palma the Elder, Nymph in a Landscape (c. 1518-1520; oil on canvas, 113 x 186 cm; Dresden, Gemäldegalerie) |

|

| Palma the Elder, Venus in a Landscape (c. 1520; oil on canvas, 77.5 x 152.7 cm; London, Courtauld Gallery) |

|

| Palma the Elder, Venus and Cupid in a Landscape (c. 1515; oil on canvas, 88.9 x 167 cm; Pasadena, Norton Simon Museum) |

|

| Palma the Elder, Venus and Cupid (c. 1520; oil on canvas, 118.1 x 208.9 cm; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum) |

|

| Palma the Elder, Bath of the Nymphs (1519-1520; oil on canvas applied to panel, 77.5 x 124 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) |

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, Venus and Cupid (c. 1525; oil on canvas, 92.4 x 111.4 cm; New York, The Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| Giovanni Cariani, Venus in a Landscape (c. 1530-1535; oil on canvas, 80.5 x 138.5 cm; Windsor, Royal Collection) |

|

| Giulio Campagnola, Venus in a Landscape (1510-1515; engraving, 121 x 182 mm; London, British Museum) |

Campagnola’s engraving is interesting because, unlike with all Venuses and nymphs seen so far, the protagonist has her back to the subject, but this does not prevent her from holding a hand between her legs. This gesture has been read by art historian Maria Ruvoldt as an allusion to masturbation. It has to be said that the scholar also interpreted the gesture of Giorgione’s Venus in the same way, and at least for Campagnola there would be little room for doubt, according to her: the fact is that the goddess’s legs are not crossed, but are rather slightly spread apart, a sign that the Paduan artist’s Venus is probably introducing a hand to procure pleasure. We do not know if she is resting or if she has her eyes closed because she is fully enjoying the moment she has allowed for herself: in any case, even more interesting is trying to understand for what reason she has her back to the viewer. It is probably as if Campagnola wanted to establish a kind of barrier between the woman and the viewer: her engraving is not a celebration of conjugal love, but is, if anything, a further hymn to sensuality, and this distance from the man who desires her (and which could refer back to Petrarch) makes her seductive but distant. It is in this ambiguity that probably lies the meaning of the depiction. Ruvoldt writes that “by stimulating the desire of the relative and yet forcing its cancellation, the woman seems to push the viewer beyond the tangible, beyond the physical aspects of desire, so as to reach that spiritual transcendence that makes love possible.”

Masturbation, it was said, has also been called into question for the Sleeping Venus (as well as, one might add, for the Venus of Urbino): the gesture of the goddesses, in fact, leaves room open for these possibilities of interpretation. The two poets Katharine Harris Bradley and Edith Emma Cooper, who wrote under the male pseudonym Michael Field in the late nineteenth century, dedicated a poem to Giorgione’s Venus, entitled The Sleeping Venus, where there is blatant talk of self-provoked pleasure: “Her hand the thigh’s tense surface leaves, / Falling inward. Not even sleep / Give invalidate the deep, / Universal pleasure sex / Must unto itself annex / Even the stillest sleep; at peace, / More profound with rest’s increase, / She enjoys the good / Of delicious womanhood.” It is well known that the medical treatises of antiquity (from Galen onward), to continue with those of the Middle Ages, associated awoman’s orgasm with fertility, and consequently female masturbation was accepted and recommended by physicians as it was considered functional for procreation. In essence, a further way of looking at love: we do not know if then this reading can actually find a correspondence with reality, but it must also be said that Venetian high society of the early 16th century was very open and tolerant, and that such references are not so strange in a painting produced by that cultured and sensitive context.

Reference bibliography

- Loren Partridge, Art of Renaissance Venice, 14001600, University of California Press, 2015

- Antonio Paolucci, Lionello Puppi, Enrico Maria Dal Pozzolo, Giorgione. Paintings and Mysteries of a Genius, exhibition catalog (Castelfranco Veneto, Museo Casa Giorgione, December 12, 2009 to April 11, 2010), Skira, 2009

- Sergio Momesso, Bernardino Licinio, L’Eco di Bergamo - Museo Bernareggi, 2009

- Filippo Pedrocco, Titian, Rizzoli, 2000

- Philip Rylands, Palma the Elder, Cambridge University Press, 1992

- Davide Banzato, Giorgione. All Painting, Nardini, 1988

- Daniel Arasse, Titian: Venus of Urbino, Arsenal, 1986

- Fiorenza Scalia, Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi, L’Opera ritrovata. Homage to Rodolfo Siviero, Cantini, 1984

- Jaynie Anderson, Giorgione, Titian and the Sleeping in AA.VV., Titian and Venice, conference proceedings (Venice, Università degli Studi, September 27-October 1, 1976), Neri Pozza, 1980

- Pietro Zampetti (ed.), Giorgione and the Giorgioneschi, exhibition catalog (Venice, Palazzo Ducale, from June 11 to October 23, 1955), Casa editrice Arte Veneta, 1955

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.