Not just House of the Dragon: the 5 most iconic illustrations of dragons in art history

It has been around forever, but in recent years it is known to be the creature of George R. R. Martin’s tales, which later became the Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon series: It is the dreaded fire-breathing winged dragon. In his fantasy tales Chronicles of Ice and Fire, set in a distinctly medieval universe, taming the dragons is House Targaryen itself, with its iconic coat of arms depicting a three-headed red dragon, and with its ancient history rooted in the legendary Valyria. Today, the dragons we know and have become accustomed to seeing through series are a far cry from the artistic imagery of centuries past. Do not expect princesses riding them, knights on their backs, or creatures spitting tongues of fire at the command of “Dracarys.” The dragon is an ancestral figure that has always been linked to evil and can already be found in the paintings and stories of ancient Greece under a different guise.

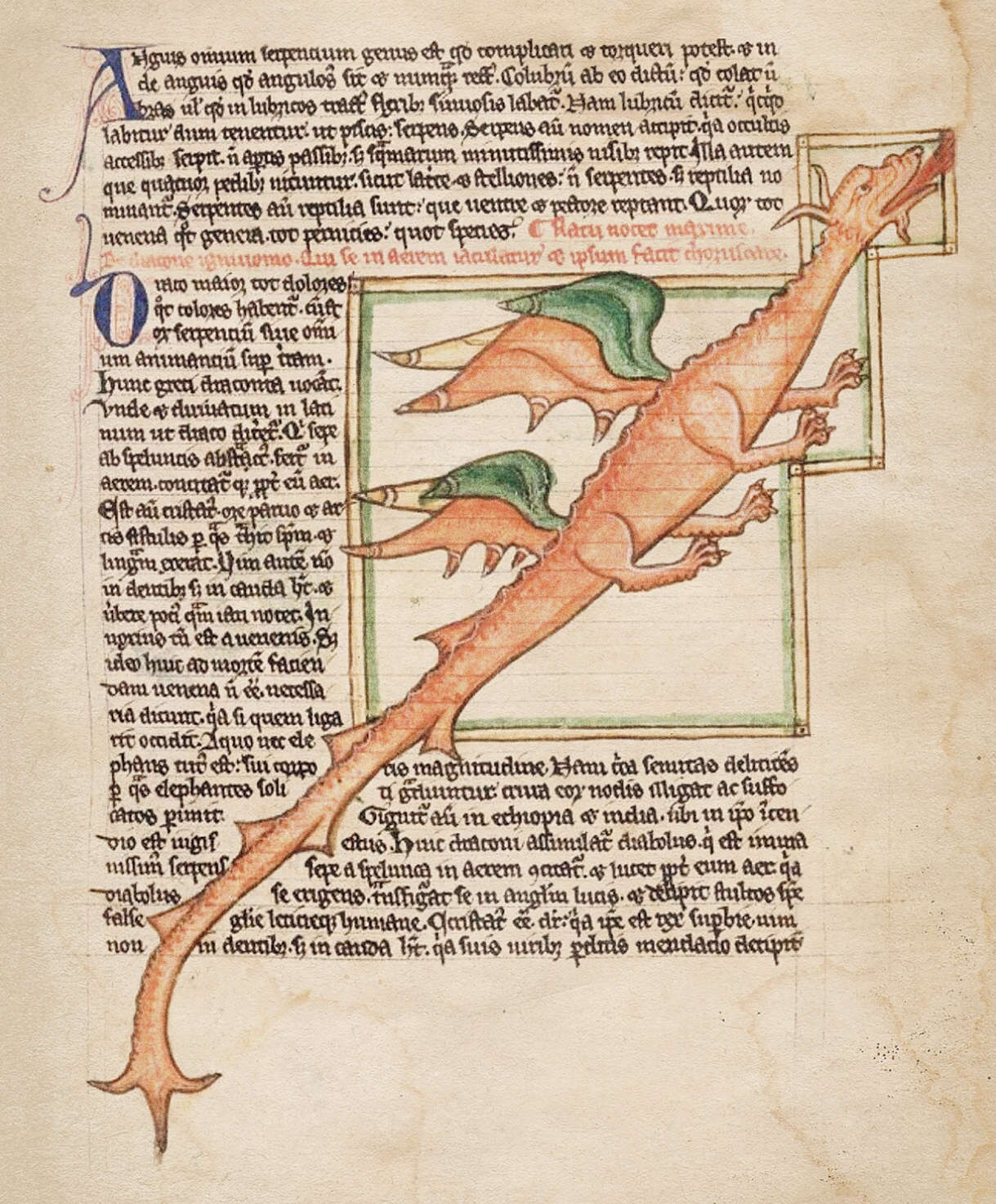

At that time the dragon, called a drakon, had a snake-like appearance. The most famous is surely theHydra of Lerna, the creature defeated by Hercules in the second of his twelve labors. Its characteristic feature is in fact that it possesses hundreds of heads. But how did we arrive at the representation of the dragon that we all know today? Only in the Middle Ages does its figure begin to approach the one we have imprinted in our minds today. The creature begins to breathe fire, possesses a face resembling that of a wolf or a cat, and has powerful legs and bat-like wings that allow it to fly. Where, however, did the image of the fire-breathing dragon come from? One of the earliest descriptions of a monstrous creature spewing flames from its mouth is that of the Leviathan in the Book of Job, which is depicted thus, “Behold, thy hope is failed, / At the mere sight of it one weeps. / [...] I will not be silent about the strength of his limbs: / In strength he has no equal; / Who ever opened on his front the mantle of skin / And in his double armor who can penetrate? / The doors of his mouth who ever opened? / Around his teeth is terror! / His back is in sheets of shields, / welded with tight seal; / one with the other touching, / so that air between them does not pass: / [... ] His sneeze radiates light / and his eyes are like the eyelids of the dawn. / From his mouth flashes forth, / sparks of fire shoot out. / Out of his nostrils comes smoke / as from a boiler, boiling on fire. / His breath sets coals ablaze / and out of his mouth come flames. / In his neck resides strength / and before him runs fear. / The yokes of his flesh are well compacted, / they are firmly on him, they do not move.” Thus, Christian art could not disregard this description in imagining the fearsome creature, beginning with the pages of the bestiaries, the medieval books that described the characteristics of all animals, real or fantastic: in this sense, one of the most famous dragons, likely the basis for so many other depictions, is the one found in the Harley manuscript MS 3244 preserved in the British Library in London (it dates from around 1255-1265), and it has the characteristics we all associate with dragons today: the appearance similar to that of a monstrous crocodile, bat-like wings, horns, and a mouth from which fire comes out. This is one of the very first images of a fire-breathing dragon as we commonly understand it today in Western art history, according to some scholars the first tout court.

All these aspects are represented excellently by Raphael and Paolo Uccello in their paintings depicting St. George and the dragon. Some depictions, especially those related to theApocalypse of John, even illustrate him red and with seven heads. Renaissance naturalists, on the other hand, devote entire encyclopedic volumes to it, such as the Bolognese Ulisse Aldrovandi, while more modern artists such as Gustave Doré depict it in the guise of the sea monster Leviathan. So here are five of the best-known dragons in art history, which inspired the famous Drogon, Vhagar and Syrax from House of the Dragon and Game of Thrones.

1. Heracles and the Hydra of Lerna, Attic black-figure amphora.

The National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome preserves an artifact dating from 540-530 BCE. It is an Attic black-figure amphora attributed to the Michigan Painter found in the Martini Marescotti tomb within the Banditaccia necropolis in Cerveteri. The representation that appears on the pottery depicts the second of the twelve labors that Eurystheus inflicts on Heracles: theslaying of the Hydra of Lerna. Mythologically, the hydra is a creature daughter of Echidna and Typhon that lives in the Lerna swamp in Argolis, Greece. It takes the form of a serpentiform aquatic dragon with countless heads. Unlike medieval dragons, Greek dragons resemble the forms of snakes, which is why they do not breathe fire and possess neither wings nor legs with claws. In legend, the dragon’s severed heads continuously regenerated, making the creature invincible. Only by decapitating the middle head, considered the only immortal one, and cauterizing the wounds, was the hero finally able to defeat it. In this case, the amphora reproduces exactly this scene. Indeed, the Greek dragon with its serpentine form is one of the most ancestral figures ever depicted in Greek art.

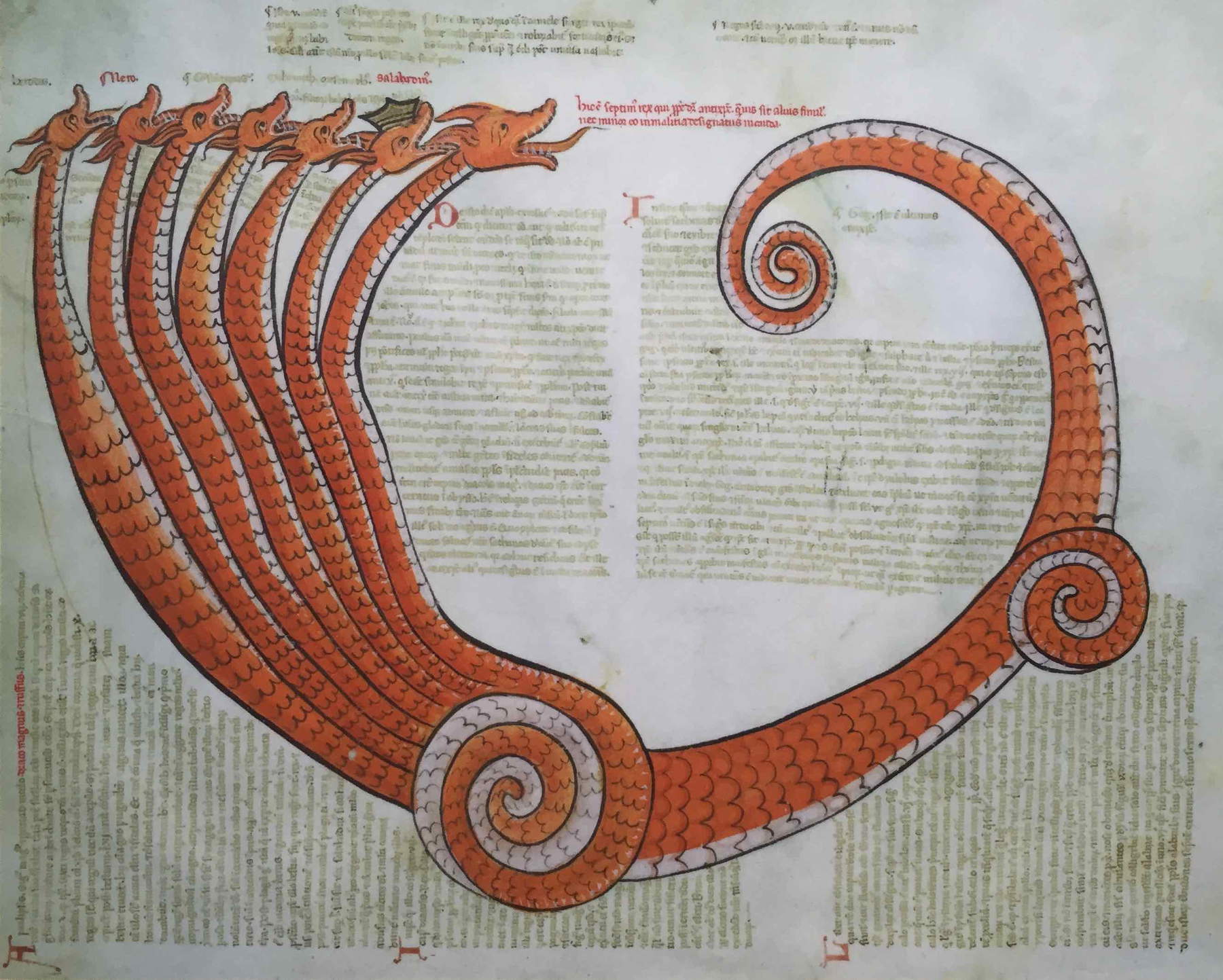

2. Liber Figurarum, The seven-headed dragon of the apocalypse.

The Liber Figurarum - Book of Figures - is an illuminated manuscript from the 12th century, which reports the thoughts of the philosopher Joachim of Fiore (Celico, c. 1130 - Pietrafitta, 1202) and collects several illustrated figures. These include the Dragon of the Apocalypse, depicted in theApocalypse of John as a blood-red dragon, a symbol of violence, with seven heads and ten horns that bore seven diadems on its heads while its tail dragged the stars of heaven, causing them to fall to earth. The dragon depicted by the illuminators of the Liber Figurarum looks exactly like this. The symbolism of the dragon recalls that of the ancient serpent that caused the first mortal sin. In this respect, the dragon becomes a symbol of the evil that has acted and continues to act in human history in an evil way.

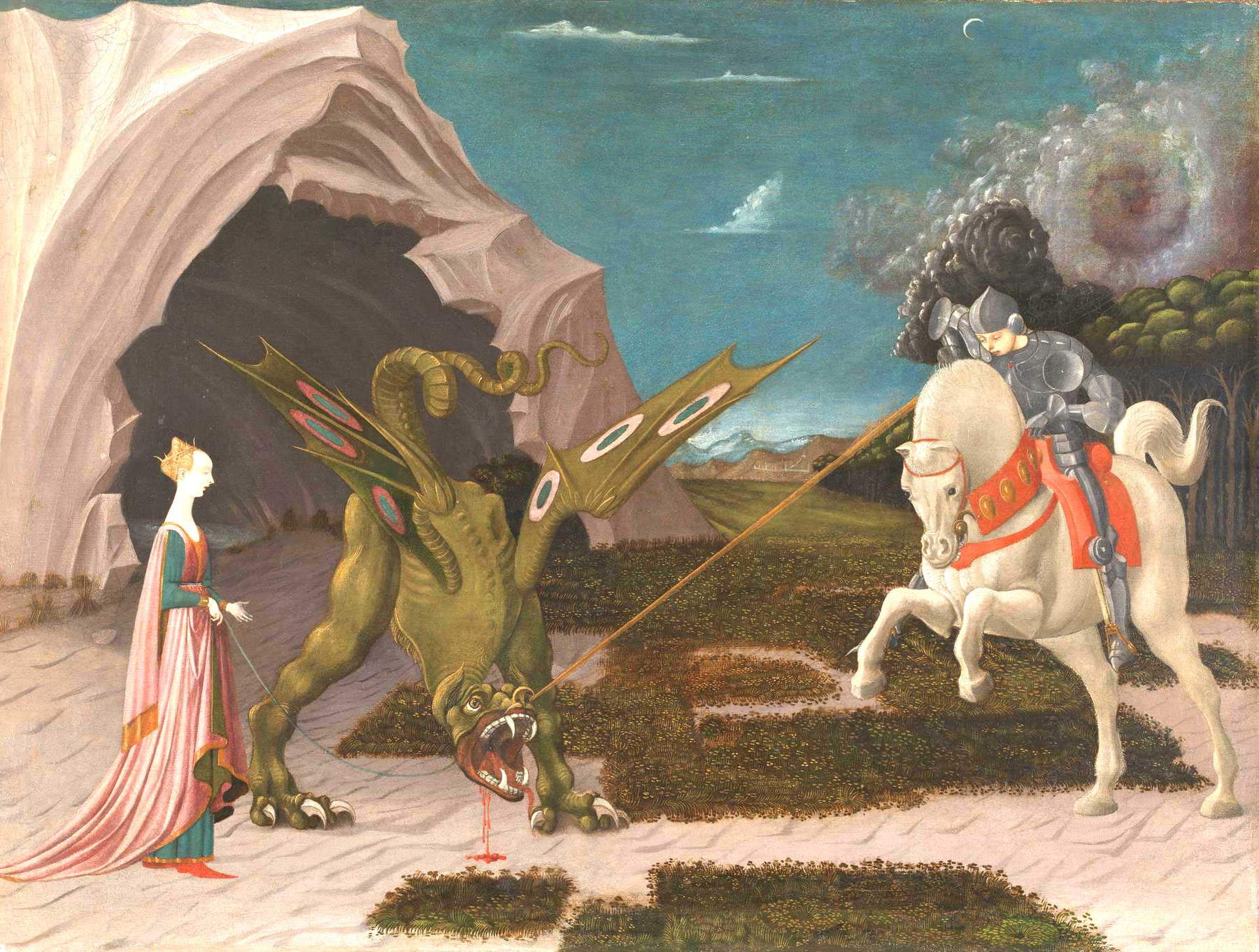

3. Paolo Uccello - Saint George and the Dragon

Preserved at the National Gallery in London, the painting St. George and the Dragon by Italian painter Paolo Uccello (Pratovecchio, 1397 - Florence, 1475) captivates visitors with its arrangement of elements, its centered perspective and its fairy-tale-like scene. Inside the painting is the depiction described in the Legenda Aurea, a collection of hagiographic lives composed by Iacopo da Varazze begun around 1260 and completed in 1298. The texts of the Legenda tell the story of a dragon that lived in a large pond in the city of Silena, Libya. Its inhabitants, terrified of the creature, offered animals to appease its instincts, until the king’s daughter was chosen as the next offering. The ruler, desperate, offered his wealth and his kingdom to save the princess. When the young girl arrived by the pond, St. George witnessed the scene and decided to intervene, piercing the dragon with his spear. A symbol of Christian faith prevailing over instinctive impulses, St. George has become today the symbol of reason triumphing over irrationality. In Paolo Uccello’s work, the creature’s cave can be seen in the background and a swirl of clouds forming a spiral in the upper right part of the painting. Over the years, not only the artist portrayed this scene that has become iconic in art history: even Raphael, in 1505, depicted the moment when St. George pierces the dragon at his feet.

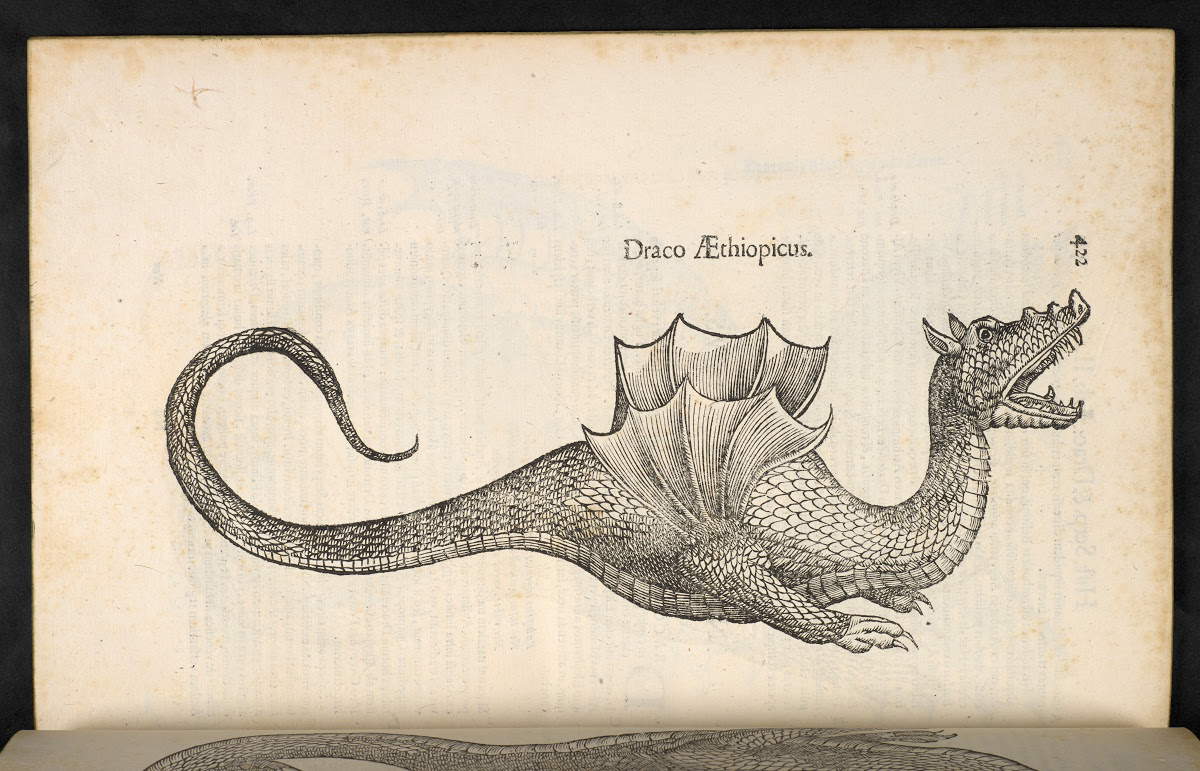

4. Ulysses Aldrovandi - Serpentum et Draconum historiae.

When the Serpentum et Draconum historiae was published in 1640, its author, naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi (Bologna, 1522 - 1605) was already dead. Serpentum et Draconum historiae is still today an encyclopedic work that constitutes among the most comprehensive volumes devoted to the world of snakes and dragons. Indeed, within it are countless creatures, both real and mythological. Flanked by illustrations such as those of Draconis Alati, Draco Aethiopicus and Draco Alter Aethiopicus mas cum eminentijs dorsi, are the respective descriptions that include tales and legends. Although more detailed information about Aldrovaldi’s volume is not available today, the manuscript remains among the most comprehensive works related to the world of serpentiform and mythological figures.

5. Gustave Doré - Destruction of Leviathan.

Among his countless works, which are considered true masterpieces, engraver, lithographer and painter Gustave Doré (Strasbourg, 1832 - Paris, 1883) decided to add to his list the 1865 engraving Destruction du Léviathan, the destruction of Leviathan, made for the illustrated Bible(La Grande Bible de Tours, so known because it was first published in 1866 by the publisher Alfred-Henry-Armand Mame who was based in the city of Tours, France). Drawing on Hebrew biblical accounts, and in particular the very Book of Job, Doré illustrates the moment when God lashes out at the creature, killing it. Leviathan, a serpentiform demonic dragon that almost echoes the iconography used in Greece, represents chaos, death, and envy. It has often been used for depictions of the Mouth of Hell: one of the earliest such images is a stained-glass window in the Cathedral of Bourges in France, dating from the 12th century, while in Italy in 1555 Giacomo Rossignolo had depicted Leviathan as the Mouth of Hell in his fresco of the Last Judgment (in the church of Madonna dei Boschi in Boves, near Cuneo). In the scene with dramatic and dark features that Doré depicts, the dragon stands with its mouth wide open inside a watery whirlpool. Its tail is almost turned in on itself and its body twisted. High in the clouds, God points his sword at the creature, slightly anticipating the moment before its death. Nevertheless, in some biblical accounts Leviathan is not always associated with the negative, but is also described as an oceanic creature that is part of God’s many living creatures.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.