Noble simplicity and quiet grandeur: Winckelmann and the foundations of neoclassicism

One could not understand neoclassicism without referring to the figure of the main theorist of this movement that developed in the second half of the 18th century and also distinguished much of the following century: we are talking about Johann Joachim Winckelmann (Stendal, 1717 - Trieste, 1768), author of the seminal essay Pensieri sull’imitazione delle opere greche nella pittura e nella scultura (original title: Gedanken über die Nachahmung der Griechischen Wercke in der Mahlerey und Bildhauer-Kunst), published in 1755. In this essay, an essential passage for understanding neoclassicism appears. Here it is in full:

“The general and principal characteristic of the Greek masterpieces is a noble simplicity and quiet grandeur, both in position and expression. Like the depth of the sea which always remains still no matter how agitated its surface, the expression of Greek figures, however agitated by passions, always shows a great and posed soul” (Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture in The Beauty of Art, Einaudi, 1948).

We often read or hear the words noble simplicity and quiet grandeur (in the original German: edle Einfalt und stille Größe) when talking about neoclassicism: at lectures, in books, in presentations, or in the caption panels of exhibitions. Sometimes, however, the meaning of these words, which alone perhaps contain the essence of neoclassicism, eludes us: to understand them best, therefore, we must drop into the reality of the artistic context of the 18th century. A reality in great ferment, especially after the discoveries, in 1738 and 1748 respectively, of the ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii, which awakened a passion for antiquity in the artists and intellectuals of the time. The echo of this discovery pervaded the whole of Europe, attracting travelers from all over the continent to this part of Italy. Winckelmann himself visited Pompeii and Herculaneum, albeit only in the late 1950s, thus after publishing his Pensieri: the visit, however, would be crucial for him in writing his later works. One of the positive consequences of this renewed love of antiquity was thescientific approach to the art of the past: scholars began to draw up catalogues, conduct excavation campaigns, and study the evidence of classical art with philological criteria. And such interests did not concern onlyRoman art, which for centuries had been the “standard” to which artists referred: intellectuals began to deal extensively and systematically with the artistic productions of other civilizations, such as Greek, Egyptian, Etruscan, and others.

Until then, looking at classicism meant, essentially, looking at Roman art: the judgment of intellectuals, beginning in the sixteenth century, was conditioned by Giorgio Vasari, who in his Life of Andrea Pisano asserted that Roman art was “the best, indeed the most divine of all others.” The cultural climate that developed in the eighteenth century challenged the primacy hitherto accorded to Roman art: previously, no one had bothered to make distinctions between Greek and Roman art, since everything was brought back under the “category” of classicism. Eighteenth-century scholars therefore began to wonder about the differences between Greek and Roman art and, therefore, how the two civilizations declined classicism. It was Winckelmann himself who profoundly revisited Vasari’s judgment: indeed, the German art historian believed that the Greeks were superior to the Romans. Incidentally, Winckelmann’s own judgment conditioned aesthetic tastes at least until the early twentieth century (with the exception, however, of Romanticism), when there was a complete revaluation of Roman art.

But why was Winckelmann a firm believer in the superiority of Greek art over Roman art? Winckelmann believed that art was born in a climate of freedom, and since he also believed that the Greeks were truly free men in that they lived, unlike the Romans, in a state based on a true and effective democratic system, Greek art, according to Winckelmann’s logic, could only be freer and thus hold primacy over Roman art. The German historian was also convinced that the flourishing of the arts in ancient Greece had its beginning at a specific time: that of the expulsion of tyrants and the subsequent emergence of the democratic form of government in ancientAthens. This, then, is the main reason why Winckelmann was an ardent proponent of the superiority of Greek art over Roman art: the latter could only consist of a copy, decadent and devoid of values, of Greek art. Just as decadent, according to Winckelmann, was the art contemporary to him, which depended on the will of a ruler, his court, and the patrons who frequented it: remember that Winckelmann was born in the kingdom of Prussia. Indeed: it is possible that his essentially Enlightenment thinking and thus his aversion to monarchical regimes (which often and frequently drew inspiration from the model of theRoman Empire) had contributed to forming his opinion on the superiority of Greek art over Roman art.

|

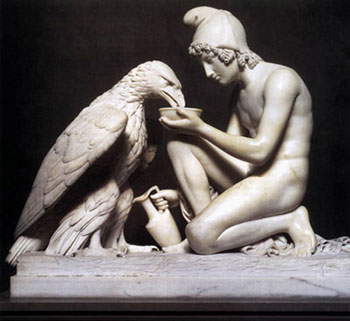

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Zeus and Ganymede, 1817, Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum |

Then add another important fact: Rome is the seat of the papacy, which in Winckelmann’s time was one of the most influential (and probably most despotic) monarchies in Europe. The Church had dictated European artistic taste throughout the seventeenth century, promotingBaroque art. Winckelmann was always extremely critical of Baroque art, which was seen as a degenerate art based on technical virtuosity and bizarreness. Bizarre and harmony are two concepts that cannot go together. And since Rome as the seat of the papacy could be compared to Rome as the seat of the Roman Empire, it was natural to make comparisons between Baroque art and imperial art.

This thought about Greek art could not fail, of course, to invest Greek art’s conception of beauty. The Greeks, according to Winckelmann, were the civilization that more than any other succeeded in realizing an art characterized by formal purity, harmony, balance, and absence of disturbance: and this, precisely by virtue of their very high degree of freedom. And it is therefore here that the definition of the masterpieces of Greek art as masterpieces characterized by noble simplicity and quiet grandeur fits in. To best understand this concept, we can use the same example proposed by Winckelmann in his work: the celebrated Laocoon. This is a sculpture, of uncertain dating (dates ranging from the first century B.C., to the first century A.D., have been proposed), known through a Roman copy dated to the first century A.D., which depicts the famous episode from Virgil ’sAeneid in which the Trojan priest Laocoon is told of being dragged into the sea, along with both of his sons, by two enormous sea serpents sent by Athena so that Laocoon would not hinder the Greeks’ plan to conquer Troy. Laocoon, in fact, had warned his fellow citizens not to trust the horse sent as a gift by their rivals.

In his Thoughts, Winckelmann contrasts Laocoon ’s tensed muscles as he attempts to wriggle out of the serpents with his expression, which is, yes, in pain, but not broken down: the pain, in Laocoon’s face, is realized, Winckelmann says, in a mouth that lets out only a labored breath and not horrible cries, like those Virgil attributes to his Laocoon in the Aeneid. This, then, is what Winckelmann means by quiet greatness: the ability to control drives, the ability to be able to communicate in a measured and balanced way sensations such as, in this case, Laocoon’s pain. Winckelmann compares the masterpieces of Greek art to the sea: no matter how disturbed the surface may be by the waves, the bottom will always remain calm. Similarly, the Greeks, in the midst of the most turbulent passions, still managed to communicate the idea of a balanced grandeur of soul: and such a soul pervades the entire work, in the sense that the grandeur of Laocoon’s soul, which endures pain, is perceived precisely by the contrast between the expression and the movement of the muscles.

The character’s quiet grandeur is thus also reflected in the pose the artist chooses to represent him: again, excessively bizarre, virtuous, disheveled, uncontrolled poses are avoided. Simple poses are preferred, but which at the same time manage to communicate, too, the greatness of a noble soul: hence why noble simplicity. However, it should be pointed out that nowadays there is a tendency to read the Laocoon not so much through Winckelmann’s interpretation but through that of Aby Warburg, who, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, reversed Winckelmann’s judgment, believing that the Laocoon was instead a sculpture endowed with an enormous and overwhelming dramatic force expressed by convulsive and nervous movements.

Returning to Winckelmann, it is important to point out how the historian argued that there was also a modern artist who was able to distinguish himself by noble simplicity and quiet grandeur: this was Raphael, the artist who by working an extreme simplification of the compositional schemes of the early Renaissance, arrived at hitherto untouched heights of harmony and balance.

But Raphael was not a man of antiquity: he was a modern. So how was it possible, according to Winckelmann, for the work created by a modern artist to achieve that noble simplicity and quiet grandeur that distinguished the works of ancient Greek art? The answer could only be one: throughimitation. Imitating the ancients was in fact, according to Winckelmann, the only way to become great, due to the fact that Greek art had reached the highest degree of formal perfection and no one could surpass it or do better. Imitating, however, did not mean copying: it meant producing original works, creatively, yet drawing inspiration from the principles that governed classical Greek art, thus making sure that lines and poses were simple and that subjects were not troubled by passions. Winckelmann’s directions formed the basis on which neoclassical sculptors moved. The artist who followed Winckelmann’s thinking most closely was not, as one might think, Antonio Canova, whose works often hint at a beating heart of passion, but rather the Dane Bertel Thorvaldsen, who succeeded in producing art in which lines are simplified to the extreme and where no trace of feeling is discernible. Thorvaldsen thus stood as the artist who more than any other embodied the concepts of the German art historian, not least because Winckelmannian aesthetics formed one of the foundations of his education: it is only a pity that Winckelmann never got to see the works of the artist who best adhered to the concepts of noble simplicity and quiet grandeur. Who knows how he would have judged Thorvaldsen’s works.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.