Nicola Bolla's painting, from Pigment Paintings to LP paintings

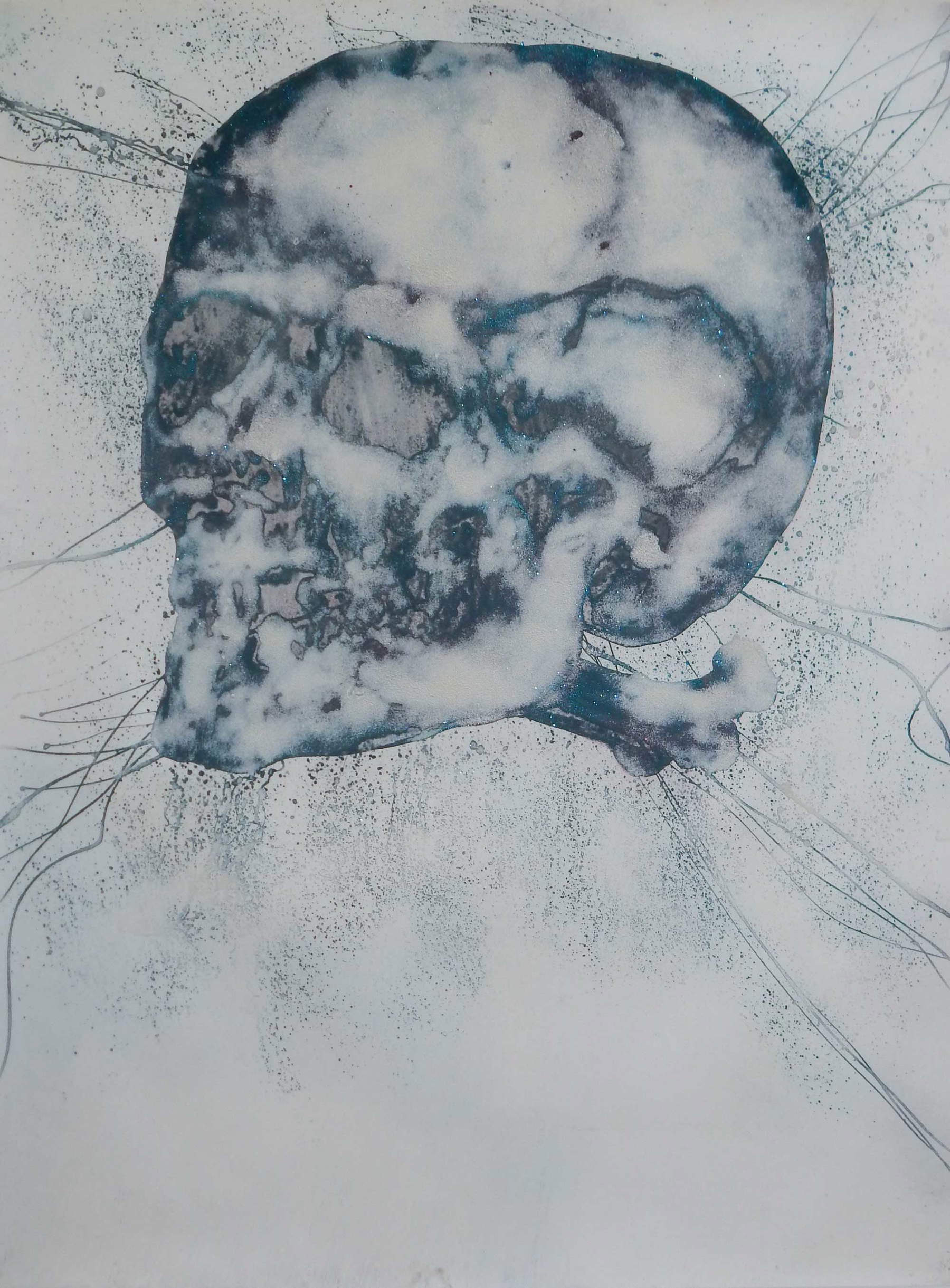

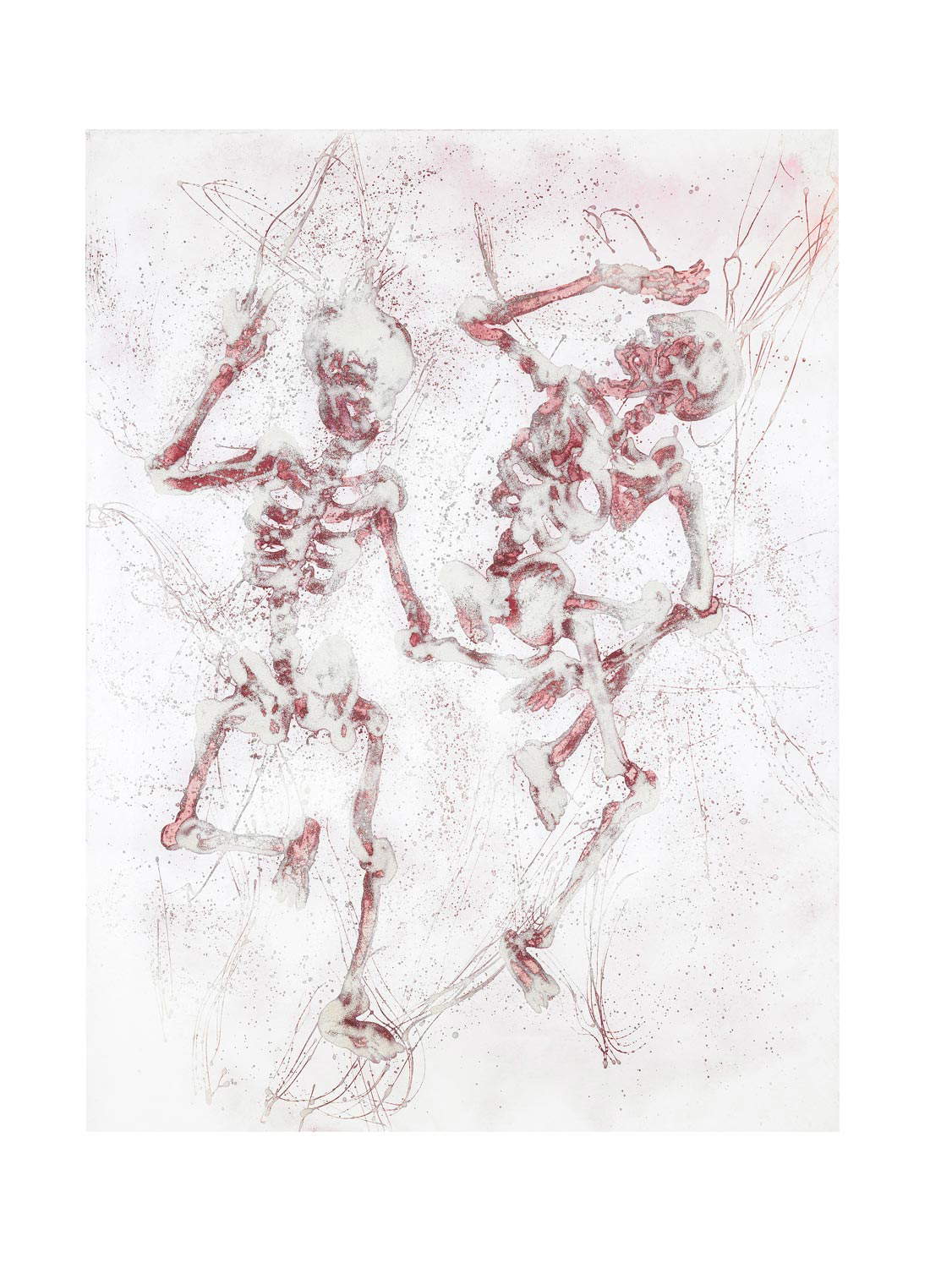

Everyone knows For the love of God, the diamond-covered skull that Damien Hirst executed in 2007 garnering worldwide praise and acclaim. How many, however, know the artist who most likely inspired it? One has to look to Piedmont, where Nicola Bolla works, who with his 1997 Skull, a skull entirely covered in Swarovski crystals, preceded Hirst by exactly ten years. Those who wish to delve into his art will discover a production that abounds with glittering skulls, skeletons and bones that remind the viewer of the finiteness of our earthly life. These are vanitas that find their roots in the art of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, a source on which Nicola Bolla’s work has always drawn: the horrific memento mori of Jacopo Ligozzi, who inserted decaying heads above shelves filled with gold and jewels, immediately come to mind. Bolla substitutes Ligozzi’s jewels with another symbol of transience, Swarovski rhinestones: the result is a pop vanitas capable of speaking to a contemporary audience, to an audience that seems to have removed the idea of death from its ideal horizon, and this despite the fact that we are, paradoxically, in what sociologist Michael Hviid Jacobsen has called “the age of spectacular death,” that is, an age in which death is continually spectacularized but it is difficult to talk about it in a meaningful, profound way (in Jacobsen’s words: “death today seems to be a spectacle we witness at a safe distance, but without ever coming close enough to it to be familiar with it”).

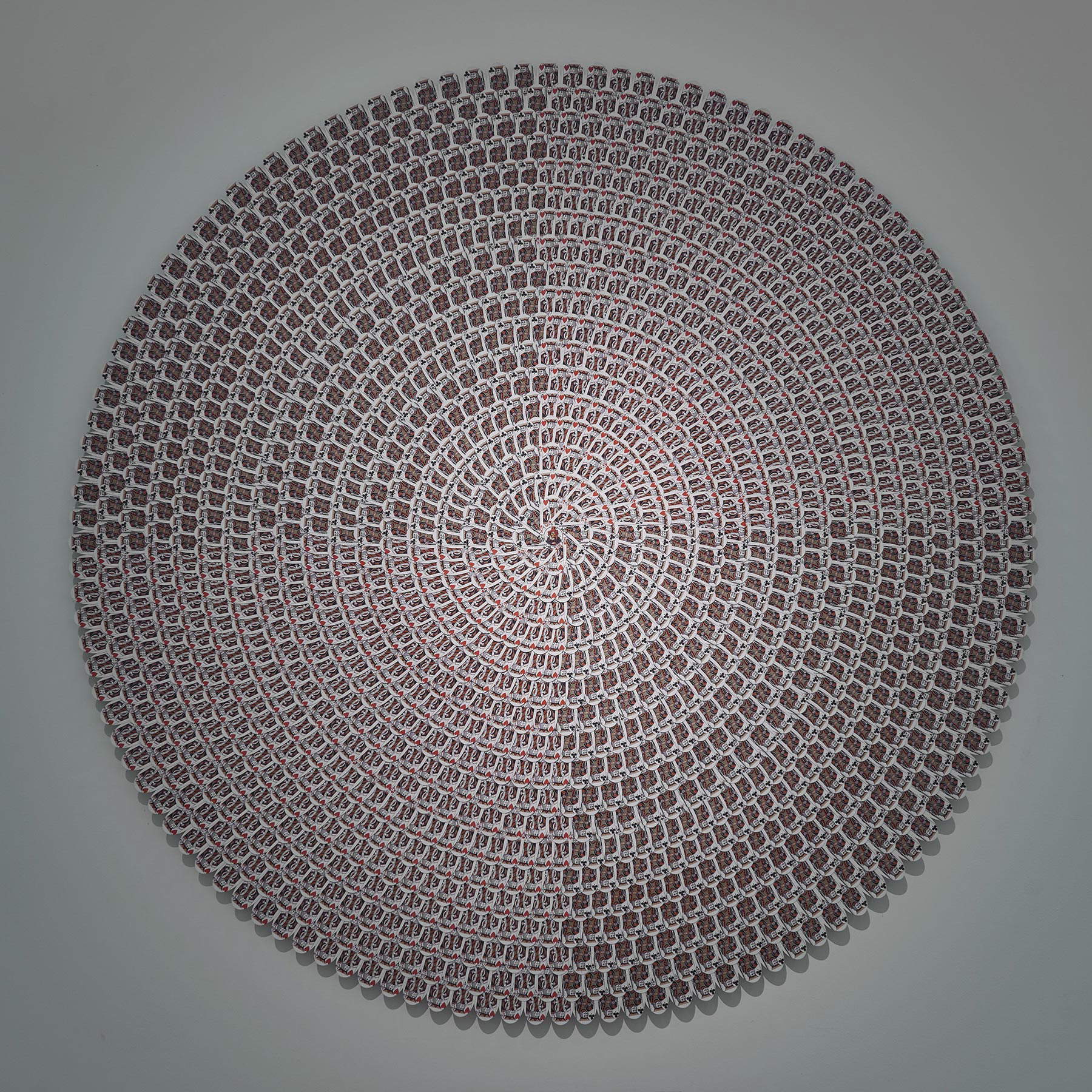

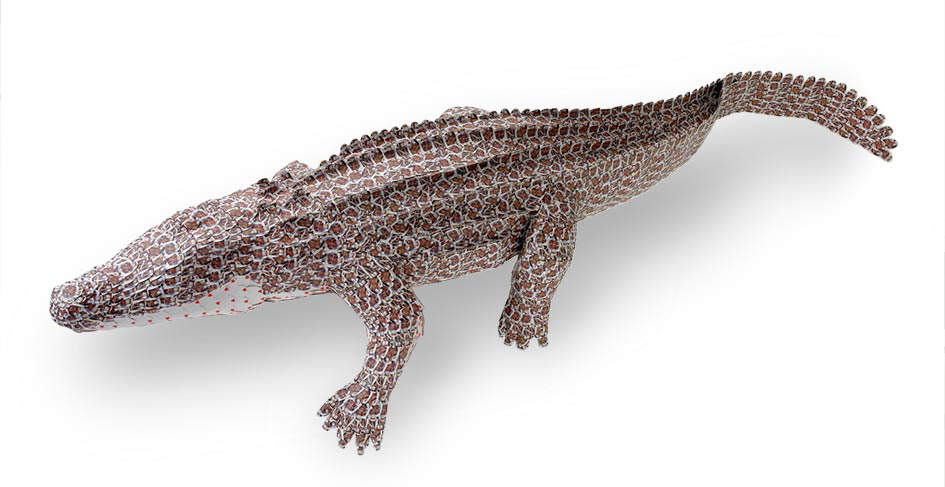

The vanitas are among the best-known works of Nicola Bolla, who over the years has experimented with the most diverse media, achieving success especially with playing cards, another material that embodies the idea of fragility, and with which Bolla has continuously produced skulls, animals, hypnotic mandalas, introducing into his art the idea of seriality inherent in Pop Art, to which Bolla’s work has been juxtaposed, although the similarities mostly concern tools and modalities (not least that of irony, which always pervades Bolla’s works, often characterized by an even playful attitude toward reality, an aspect, moreover, already explored in detail on these pages). The approach, however, is more omnivorous: Bolla does not simply observe the symbols and icons of consumer society in order to make them his own, or to welcome elements of popular culture into his work. Not least because this is not always the case: the subjects of his works do indeed gather from the pop repertoire (think, for example, of the microphones in Orpheus’ Dream, the work he took to the Italian Pavilion of the 2009 Venice Biennale), but they also look to ancient art, to distant cultures. Therefore, it could be said that Nicola Bolla rather has the curious and open gaze of the seventeenth-century collector who went in search of the strangest and most bizarre objects, fishing in the universe of nature or among the most unusual artificialia produced by the human being’s flair: he himself, fascinated by the ancient Wunderkammer, is a passionate collector of singular antique objects. And his production also bears numerous traces of such varied and multifaceted interests.

Nicola Bolla began his path in art early, which he followed in parallel with his path in medicine (besides being a successful artist, he is also an established ophthalmologist). A child of art, he formed himself, feeding on what he saw around him: the works of his father Piero (who, however, Nicola reiterates, did not teach him anything, nor did he even impart to him the first technical rudiments), the works of the Piedmontese poveristas (starting with Giuseppe Penone, a point of reference), the ancient works he admired at exhibitions and museums. He began exhibiting in the early 2000s, dividing his time between Italy and New York, where his works with Swarovski crystals have received much acclaim (on the banks of the Hudson, Bolla has put together four solo shows and ten participations in group exhibitions: who knows if Hirst was in the audience). Between 2007 and 2009 the definitive consecration with a series of consecutive successes: first the solo show at Sperone’s in New York, then the participation in the 13th Sculpture Biennale in Carrara, and finally, in 2009, the “convocation” for the Italian Pavilion of the Venice Biennale. And always with crystals: In New York, a brilliant prison cell with which Bolla invited the public “to reflect on a world built around the beauty and appearance of objects,” despite the fact that “jewelry hides a deep sense of melancholy” (so Alberto Fiz wrote on that occasion), in Carrara Vanitas Church, a Swarovski skull wearing a cardinal’s hat, and in Venice the aforementioned Orpheus’ Dream, the microphones that later became part of the roster of his most famous works. The beginning of Nicola Bolla’s career, however, was in the sign of painting. And it is to painting that one needs to look if one wants to see a more reposed and more intimate Bolla. And also less well known: as opposed to sculptures, his paintings and papers have rarely been exhibited, despite the fact that the artist has never for a minute stopped devoting himself to painting and his work on canvas, on wood, on paper (and elsewhere) has now reached a considerable size.

Nicola Bolla,

Nicola Bolla, Nicola Bolla

Nicola Bolla Nicola Bolla,

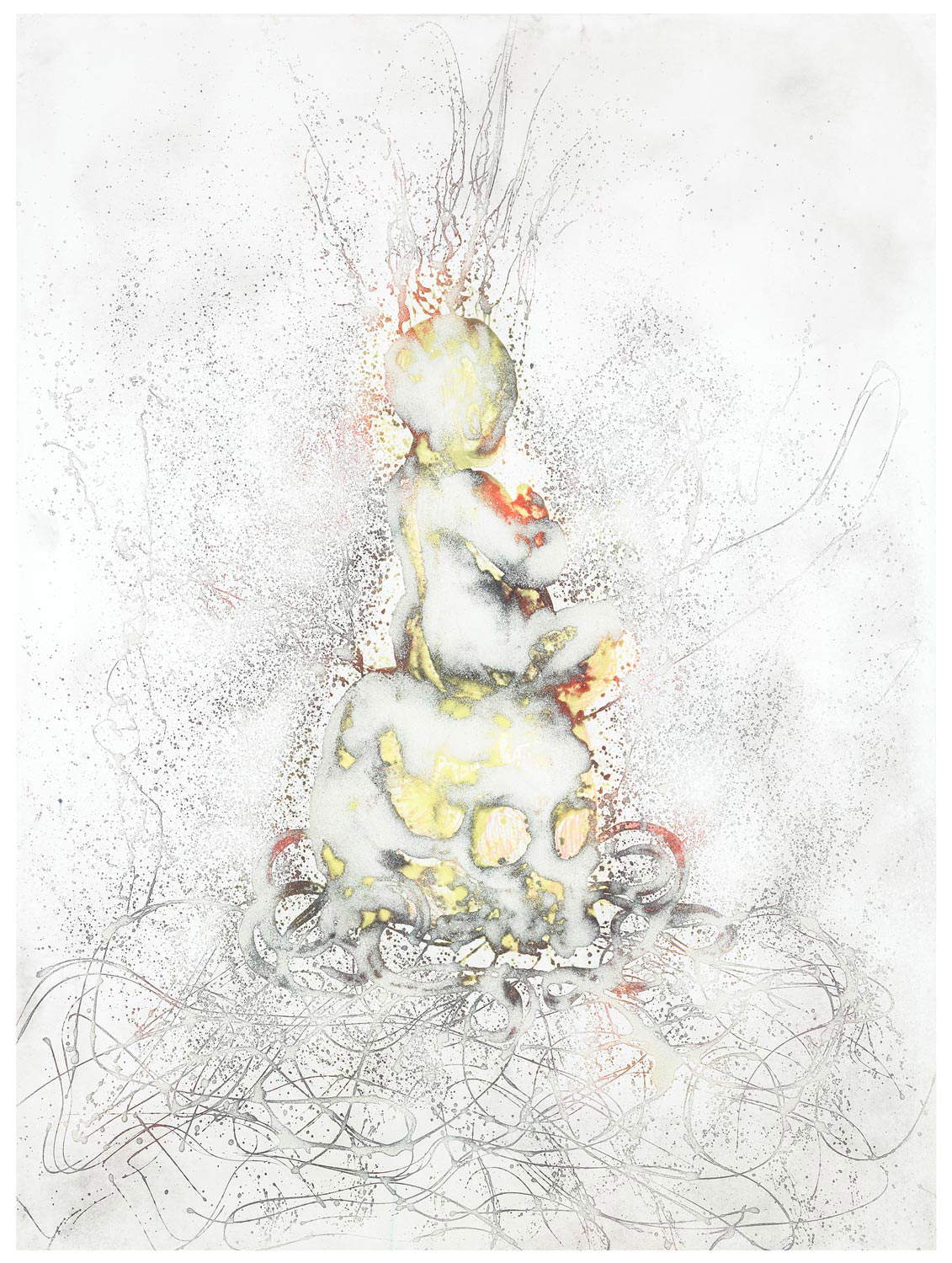

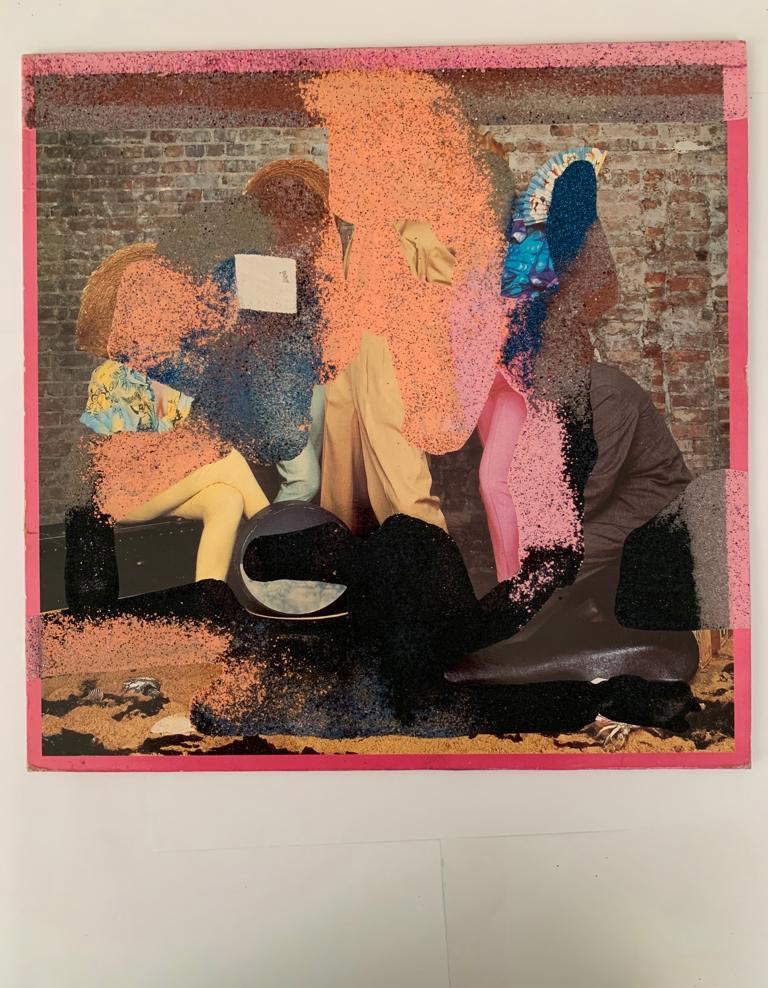

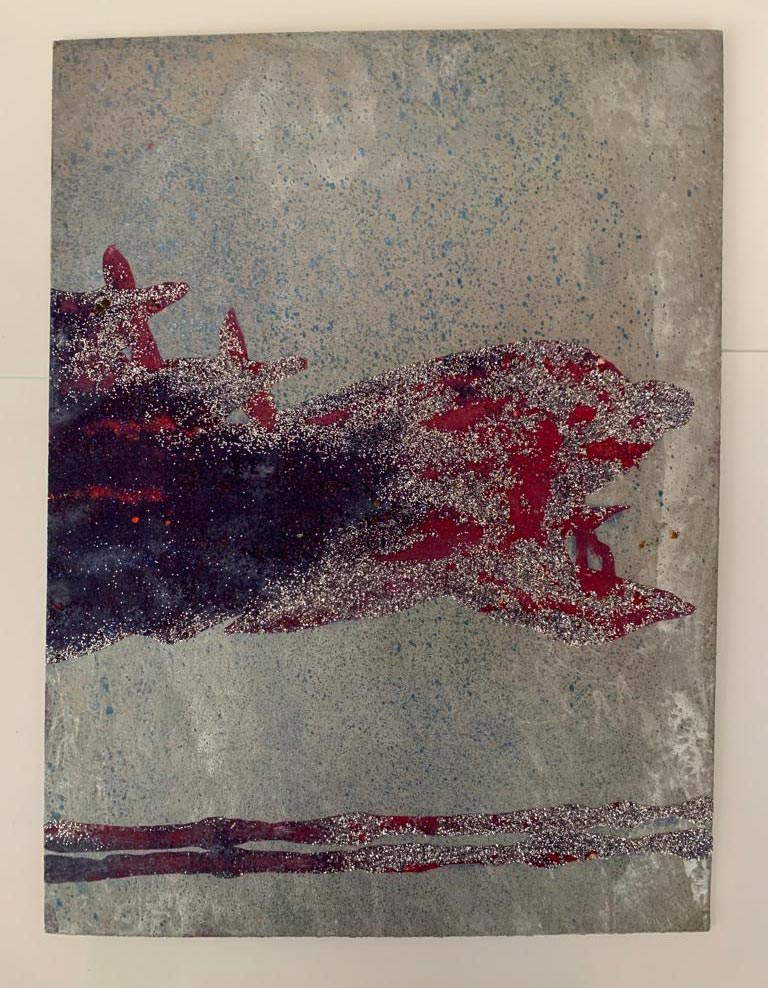

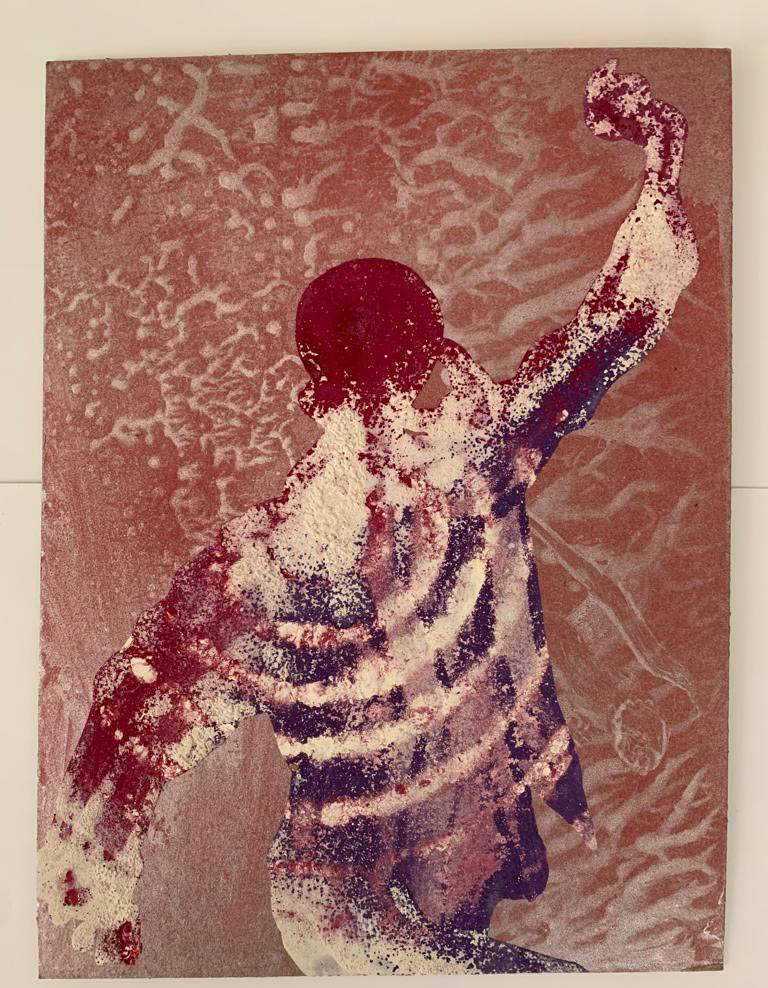

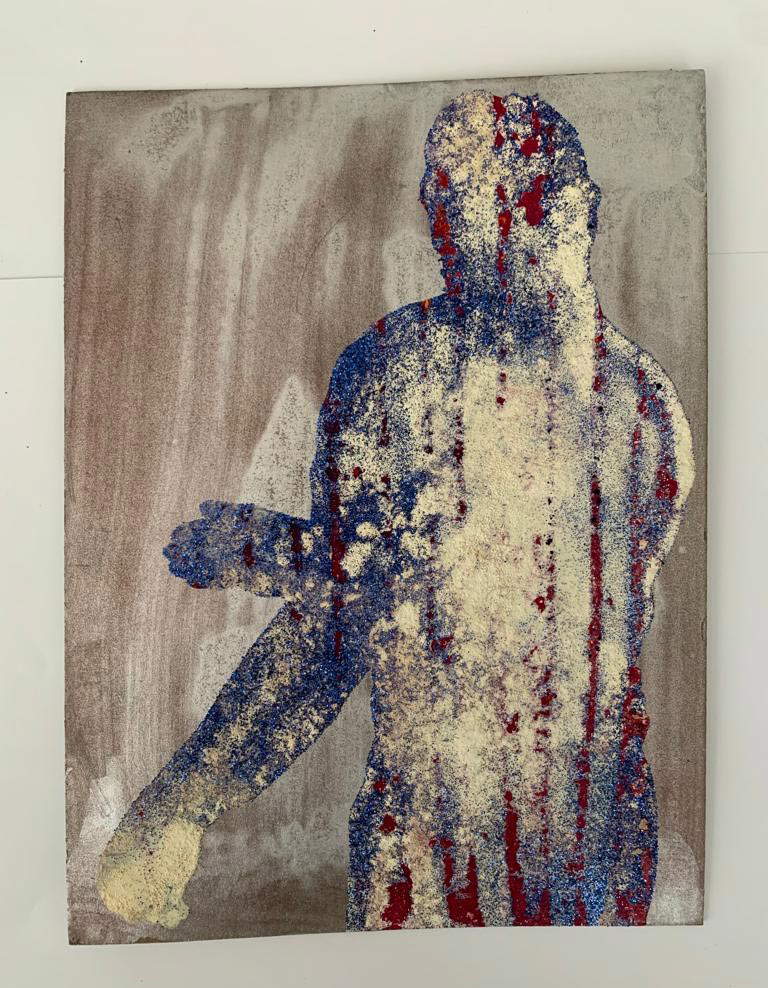

Nicola Bolla,Bolla’s painting also retains traces of his thoughts on the fleetingness of existence. “The thought of fragility,” Gabriella Serusi wrote about Vanitas Church, "of the impermanence of human existence, of the senseless vanity that governs many of the so-called ’civilized’ actions and everyday life, is reified and reduced to an object tout court. With an ironic displacement, in some respects following a paradoxical logic, Bolla entrusts precisely to the work of art - natural bearer of the values of beauty, wealth, superfluous vanity - the task of re-establishing a new order of morality, of dictating new valid parameters of judgment to orient oneself in the universe of material and immaterial goods." The reasoning could just as easily be applied to the paintings, first and foremost the Pigments Paintings and Pigments Papers, works on canvas and paper with which the artist works on images taken from the most everyday and, if you will, even the most mundane repertoire: the source image, usually a photograph, is an image that has nothing extraordinary about it. A couple sitting on a bench, a pineapple, a flower, a comic book character. But there are also heads of cardinals à la Bacon: in Bolla’s universe there are no hierarchies, no scales of value. All subjects have equal value because they belong to the same world. Bolla then begins to work on his subject by subtraction in order to reach a deconstruction, transforming the image with bright, often violent colors, making it increasingly unrecognizable: in some works in the series the subject is more easily perceived, while in others it becomes difficult to identify. In fact, the same subject is often repeated several times: as anticipated, seriality is one of the dimensions of Nicola Bolla’s art (repetition, on the other hand, is not: Bolla detests repeating himself; his production is extremely varied). Thus, pure pigment and glitter camps on a neutral background remain, allowing the viewer to open his gaze to a transfigured universe, with humble and banal objects that in part lose contact with the everyday reality from which they come to be transformed into nubile contemporary elegies, becoming dull and distant icons of our everyday life, and at the same time images similar to those of memories. Several works in the series, beginning with those on children’s comic book characters, take us back to a childlike imagination: Bolla makes no secret of having manifested his penchant for art when, as a child, he preferred to make his own toys.

Those who will have the pleasure of talking with Nicola Bolla about his Pigment Paintings will talk to an artist who is also very proud of the technique developed to ensure durability and resistance of the images. Perhaps the most immediate example is that of Yves Klein, who developed an intriguing shade of blue, his IKB (International Klein Blue), dazzling and deep, brilliant and metaphysical, vibrant and exciting, a blue that allowed him to express himself with the freedom he might otherwise never have found. The downside of the pigment he patented, however, is its fragility: Klein’s monochrome works are difficult to preserve, because the binder with which the artist fixed the color did not provide optimal protection, and the pigment’s matte finish is very easy to scratch and blur. In other words: if you rub, not even too hard, a Klein painting, it is possible that some traces of blue will remain on your hands. For confirmation, one need only ask any restorer who has dealt with his works. However, this is not a problem that only Klein’s works have: it is a worry for all painters who work with pure pigments. Instead, Bolla claims the invention of a mixture that avoids unwanted abrasion: his colors have an extraordinary durability. Even in technique, he explains, he has always tried to be original. “I have always placed myself honestly in relation to art,” he tells me: and this for him has meant “finding a personal, autonomous, independent path” even in terms of technique. The Pigment Paintings were born that way.

The glitter that makes the works in the series seductive, radiant and almost glamorous reinforces the allegorical bearing of these works: the glitter of cosmetics alludes by its very nature to superficiality and luxury, and the Pigments Paintings, under this continuous dripping of colored powder, become almost warnings reminding us of the transitory nature of our lives. And moreover, it is the exact pictorial counterpart of Swarovski crystal not only because of the imagery with which it is associated, but also because, like Swarovski, glitter is also an invention, an artificial material (Swarovski crystals were invented by Daniel Swarovski in 1862, glitter by by Henry Rushmann between the 1930s and 1940s). Sometimes the memento mori is uncovered as well, since skeletons often happen to be found among the subjects of the series. The result is projections of the inner world of the artist, who feels the need to transform, in the form of objects, his reflections on the outer world, on the reality that surrounds us. In the Pigment Paintings one may also find references to the artists who go on to compose the context within which Nicola Bolla’s art moves: the substantial irony that never abandons his work finds natural consonance in the work of the Turin artist Aldo Mondino (whose production, moreover, abounds in paintings with figures that stand out against flat backgrounds like Bolla’s), sometimes even rather explicit citations to the Poverists appear (among the Pigment Paintings the five-pointed star recurs, a distinctive feature of the research of another great Piedmontese artist, Gilberto Zorio), while the procedure can be compared to that of American pop artists. In Bolla’s way of working, philosopher Roberto Mastroianni has written, “there is a gesture heir to the best Italian and American Pop tradition, which in the artistic appropriation of common, everyday and banal elements, transfigures them and projects them into a higher, alienating and at times metaphysical dimension.”

In his paintings, Nicola Bolla continues that operation of transfiguration of the banal that sustains his sculptural production, and that implies the construction of a world of his own, a world that belongs only to him. It is an idea borrowed from so much art of the eighteenth century, a century in which many painters tended to construct parallel realities while using the same elements as real reality: think of the art of Giambattista Tiepolo, who was accustomed to creating fictitious worlds on the walls he frescoed for his patrons, worlds in which irony, however, became the privileged means of alluding instead to what inevitably remained outside the painting. In the Pigment Paintings we thus encounter the same desecrating and ironic vein that characterizes Nicola Bolla’s sculptures. The same curious and sly look that animates the works made with Swarovski crystals or playing cards. His paintings, however, are also cloaked in a lyrical dimension that is difficult to find in sculptures, which are solid, luminous presences, objects in space. The painted images take on the appearance of dreamlike visions, they remind us of the indefinite and evanescent form of what we see in a dream, they are as elusive and fluid as memories, they have the dazzling and subdued character of luminous sensations that are printed for a few seconds on the retina. Bolla’s vanitas, when on canvas and paper, become painted poems.

Nicola Bolla,

Nicola Bolla, Nicola Bolla,

Nicola Bolla, Nicola Bolla,

Nicola Bolla, Pigment

Pigment Pigment

Pigment Pigment

Pigment Pigment

Pigment

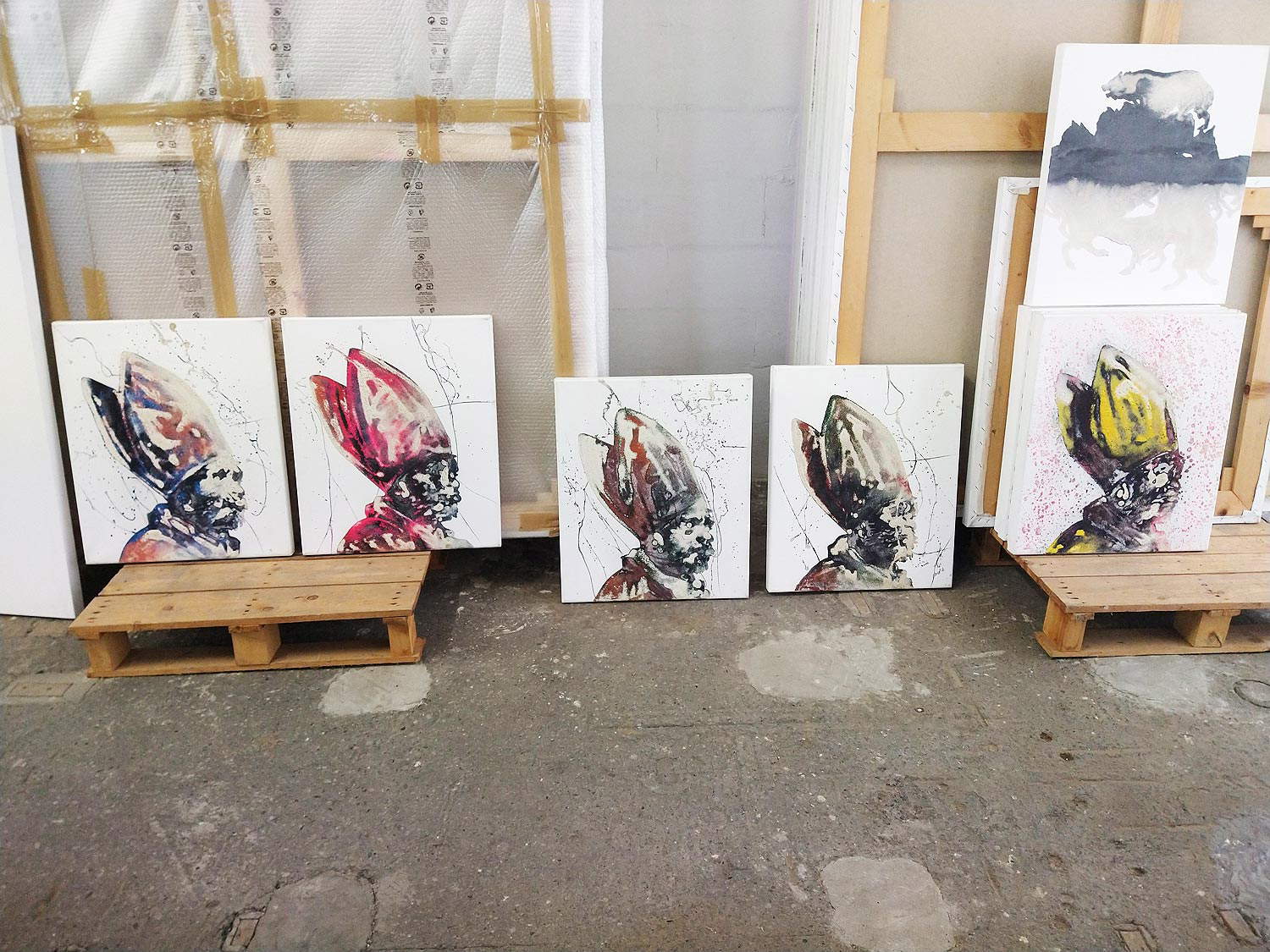

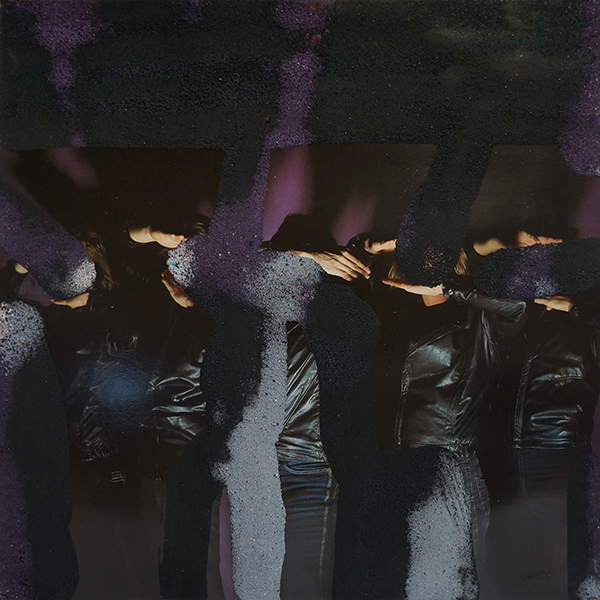

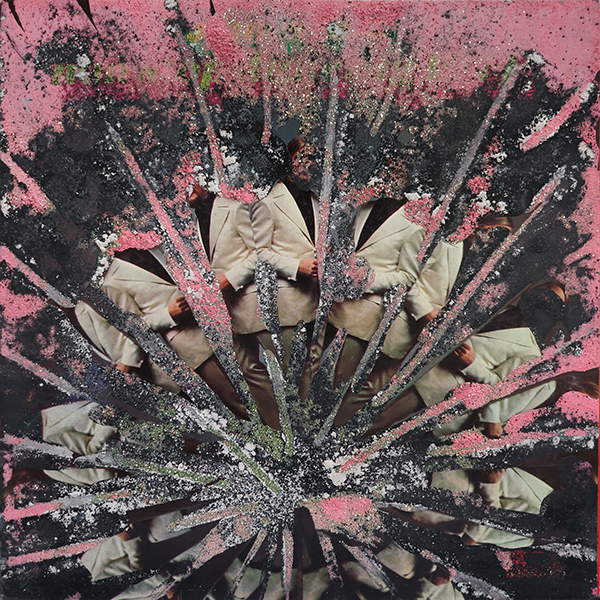

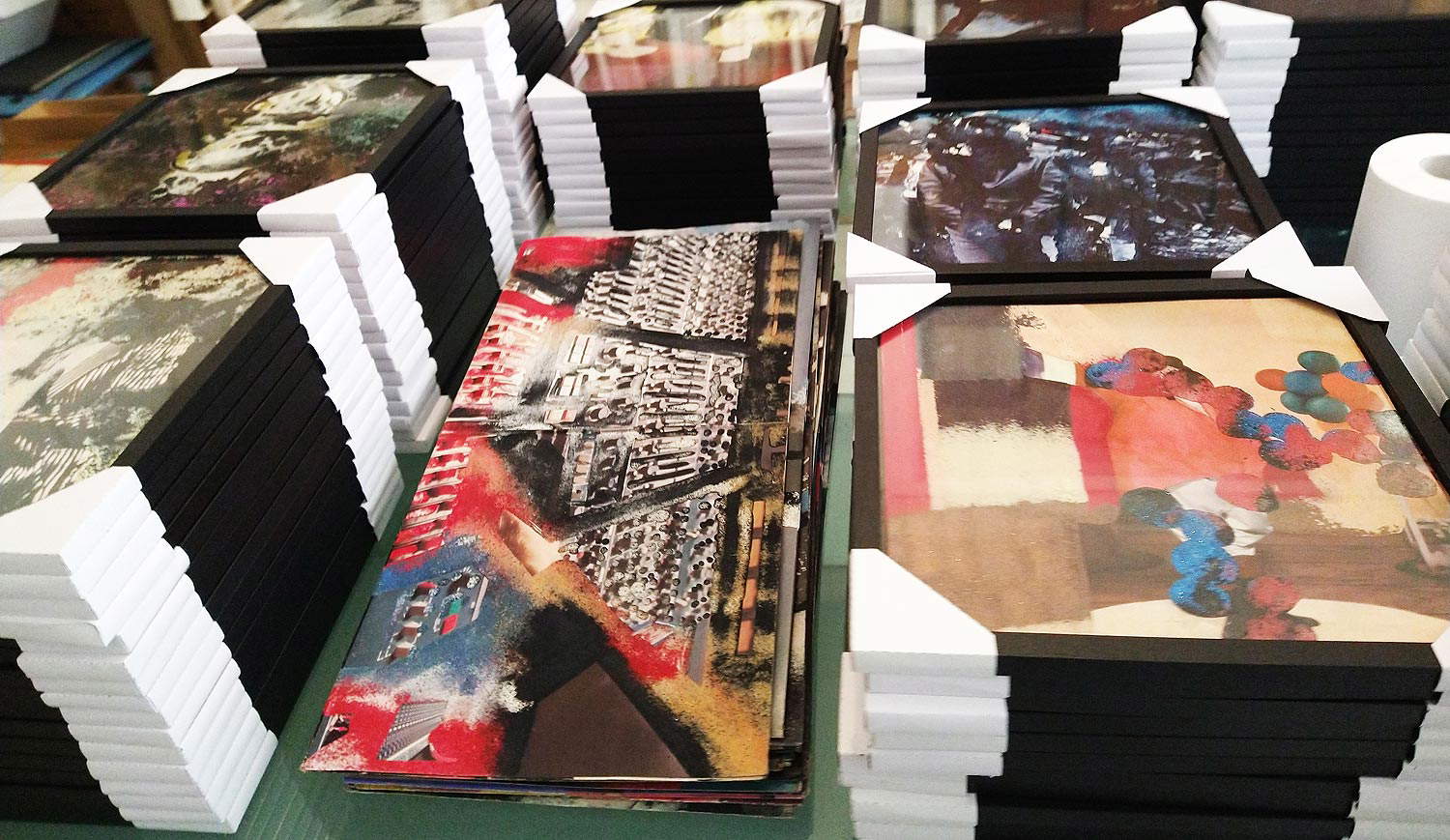

This evocative character is also found in the painted LPs, covers of 33 rpm records, all of the same format (the 30 by 30 that was, moreover, dear to Andy Warhol, who like the Piedmontese artist often worked on vinyl covers), on which Nicola Bolla has long intervened to transform the source image into a new vision that often erases the subject on the album cover altogether. In a room in his studio are piled dozens, perhaps hundreds, of records on which the artist has worked by rewriting their covers. Away with the titles, away with the names of the authors (everything that is written word is systematically erased: only the pure image must remain), often away with even what was on the cover. The idea is to reinvent not only the source work by creating a new, further layering, but also to decontextualize the object completely: those who want to will perhaps derive a different musical suggestion from it (impossible, after all, to tell who the author was from the new image), those who want to instead will quietly imagine a dimension of silence, emptiness, fragility. Even with this procedure, with a typically situationist détournement in this case, we therefore return to the reflection on vanitas that acts by means of the oxymoron triggered by the artist’s intervention.

And although the operation of rewriting an album cover may seem simple, almost obvious, the reference is lofty: Asger Jorn’s Modifications come to mind, the interventions with which the great Danish artist literally modified old decorative paintings of the late 19th or early 20th century bought for little money at flea markets, to create a new, parallel, desecrating reality, to open to new aesthetic possibilities based on spontaneity, just as spontaneous and immediate are the works on vinyl covers by Nicola Bolla. Asger Jorn’s Modifications, Daniele Panucci wrote on these pages, were “a virtuoso addition, whose power is amplified by the double register and level of painting that is sometimes harmonious and sometimes dissonant, and certainly not a desecrating operation toward the image itself or its (often) anonymous or unknown creator: the critique is directed only at society, institutions, the bourgeoisie and their gaze at art and its market.” Something similar happens with Nicola Bolla’s records. The vinyls are not removed: they are part of the work. There are works by famous artists, and there are works by musicians unknown to most, or who lived only a season: Nicola Bolla’s action, in this sense, does not deny the object of the intervention, just as Emilio Isgrò’s erasures do not deny the words on which they rain. On the contrary: Nicola Bolla’s image is like a sprout, it is life springing from another work, the value of which is perhaps even remained, despite the fact that the artist remains uninterested in the musical content. What’s more, it is a way of seeing the work from another point of view: Bolla likes to compare his way of seeing reality to that of the musicians who had the most commercial song, the hit that everyone listened to, recorded on side A, and instead left the more difficult but more heartfelt, more interesting song on side B. Transforming images means, for Nicola Bolla, following the B side of things, the one that is less flashy but in his opinion is more pregnant with meaning from the standpoint of creative thinking.

According to Nicola Bolla, a good artist is one who is able to provide those around him with his vision of the world, pointing out that there are many different points of view even when looking at the same image. His works in painting should be read from this assumption, which has always accompanied the artist since he began painting. Today Nicola Bolla is most famous for sculpture, but he himself recalls that he began painting much earlier (his first paintings date back to 1984), and that he became a sculptor almost by chance, because a designer from Turin invited him to a sculpture exhibition, challenging him to do sculpture. But his original vocation remained, and perhaps still remains, that of a painter: his beginnings were marked by small works on cardboard, which were initially inspired by comic books (in particular those of Marvel, about which Bolla has always nurtured a strong passion), and then broadened his gaze to all the reality that surrounded the artist. These small cartoons characterize Bolla’s entire career; they are intimate works, with which the artist measures himself with invention and not only with the subject. A kind of exercise, not standardized, which, however, over the years has given rise to a long story: Bolla’s small formats are all fragments of the mosaic of his life.

Nicola Bolla

Nicola Bolla Nicola Bolla

Nicola Bolla

Nicola Bolla

Nicola Bolla

Works on cardboard

Works on cardboardA mosaic, however, that has never left his studio in its entirety. The public, as mentioned, is mostly familiar with Nicola Bolla’s sculptural work. The pictorial one, on the other hand, has always remained on the margins, but the artist’s dream is to organize, sooner or later, a large exhibition that puts together all his pictorial production, an exhibition along which it is possible to stretch the thread of forty years of painting, an exhibition from which it is possible to perceive what has been the “process of evolution,” as Bolla himself calls it, that has sustained his art. A thread that at the moment can only be seen inside the studio just outside Turin. Nicola Bolla, however, has always believed strongly in his painting because it is an essential part of his artistic journey. Indeed: it is the most intimate and perhaps even the most heartfelt part of his work. Of course, the artist has no qualms about his sculpture, partly because his approach to this art has always taken painting into account: his is a “painted” sculpture, one might say, with technical solutions that try to cross the boundaries between one art and the other. It was mentioned above, for example, how glitter in painting is the counterpart of Swarovski in sculpture, but also the figures emerging from the flat backgrounds retain a monumental evidence reminiscent of that of sculptural works, while on the other hand, if we think of the sculptures with playing cards, the starting point is still a two-dimensional support, flat like a painting. Sculpture, however, retains a different malia: it is more appealing, closer to the public’s taste, perhaps because it is more spectacular, more theatrical. And so it has achieved the honors of fame with an immediacy that painting has not been granted. But Nicola Bolla has never given up painting. And sooner or later he will come out of his studio with conviction.

As I visit his studio, Nicola Bolla tells me that in his opinion intimacy sometimes creates problems of interpretation: the artist’s interiority does not necessarily match that of the collector, it is not necessarily the case that the public finds itself in what the artist thinks and expresses through his paintings. The consequence of this mismatch, we might say, lies in the behavior of the public: it is no mystery that people who buy works of art often look for paintings that will make furnishings. So many people buy works of art as if they were buying a curtain, as if the works were part of the upholstery. There is nothing wrong, of course, with aiming for a more decorative painting. The function of an artwork according to Nicola Bolla, however, is another. The work is the medium by which the artist expresses his or her worldview. And according to Nicola Bolla there is still much to be said, especially in painting. “Although many painters say that everything has already been invented and everything has already been done,” he confesses, “I think there is still a lot of room for artistic manifestations. Even painting can still have innovative spaces. The main problem is another one: that you have to have something to say. It is not so much a matter of inventing new technologies, but of being able to say something: this should be the research point of any artist.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.