In the heart of Pistoia’s historic center, in Piazzetta Spirito Santo, just a stone’s throw from the Cathedral, stands a 19th-century monument dedicated to Niccolò Forteguerri, a Pistoiese cardinal who lived in the 15th century and was known for founding in his city the Domus Sapientiae, an institute that provided an education for children and young people from needy families. It was created in 1863 by the Modenese sculptor Cesare Sighinolfi, and the base bears an inscription: “O Niccolò Forteguerri / You illustrated the Roman purple / by providing for the education of the people of Pistoia / now the orphanage and the Puccini kindergarten / raise this monument to you / to make known to the rich / that the sons of the people / do not forget the benevolent.” The monument, and also its inscription, are owed to one of the most illustrious patrons in the history of Tuscany, Niccolò Puccini (Pistoia, 1799 - 1852), who in his will expressed his firm resolve to have the sculpture dedicated to his distinguished fellow citizen who had lived four centuries earlier erected, and also dictated the epigraph to be placed at the base: his wishes were faithfully carried out.

Puccini’s will is useful for getting a fairly complete idea of who this personage was who indelibly marked the history of Pistoia in the early 19th century: the son of Giuseppe Puccini and Maddalena Brunozzi, he came from a family of professionals and landowners who, with his grandfather Domenico, had managed to enter the city’s nobility. The young Niccolò decided, however, not to follow a professional career, but to take an interest in the arts and letters and, above all, in philanthropy, which he exercised thanks to the ample economic resources he had by inheritance (mainly annuities and shareholdings) and which he knew how to manage intelligently: when he was only 25 years old, in fact, after the death of the last of his older brothers, Domenico, Niccolò Puccini became sole administrator of all the family’s conspicuous wealth, one of the largest estates in Tuscany at the time. After his studies and several trips to Italy, France, Switzerland, Holland and England in the early 1920s to complete his education, he decided to devote his entire life to patronage and philanthropy, with an eye for politics as well: Liberal-minded, in his early twenties he bestowed donations in support of the cause of Greek independence, and then followed with interest the events of the Risorgimento, going so far as to be the sole financier of the “Society of Parental Honors to Great Italians”, a patriotic association founded in 1821, and even in 1848 auctioned off the family silverware to support the Tuscans participating in the uprisings of that year (for these reasons he was also watched by the police of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany).

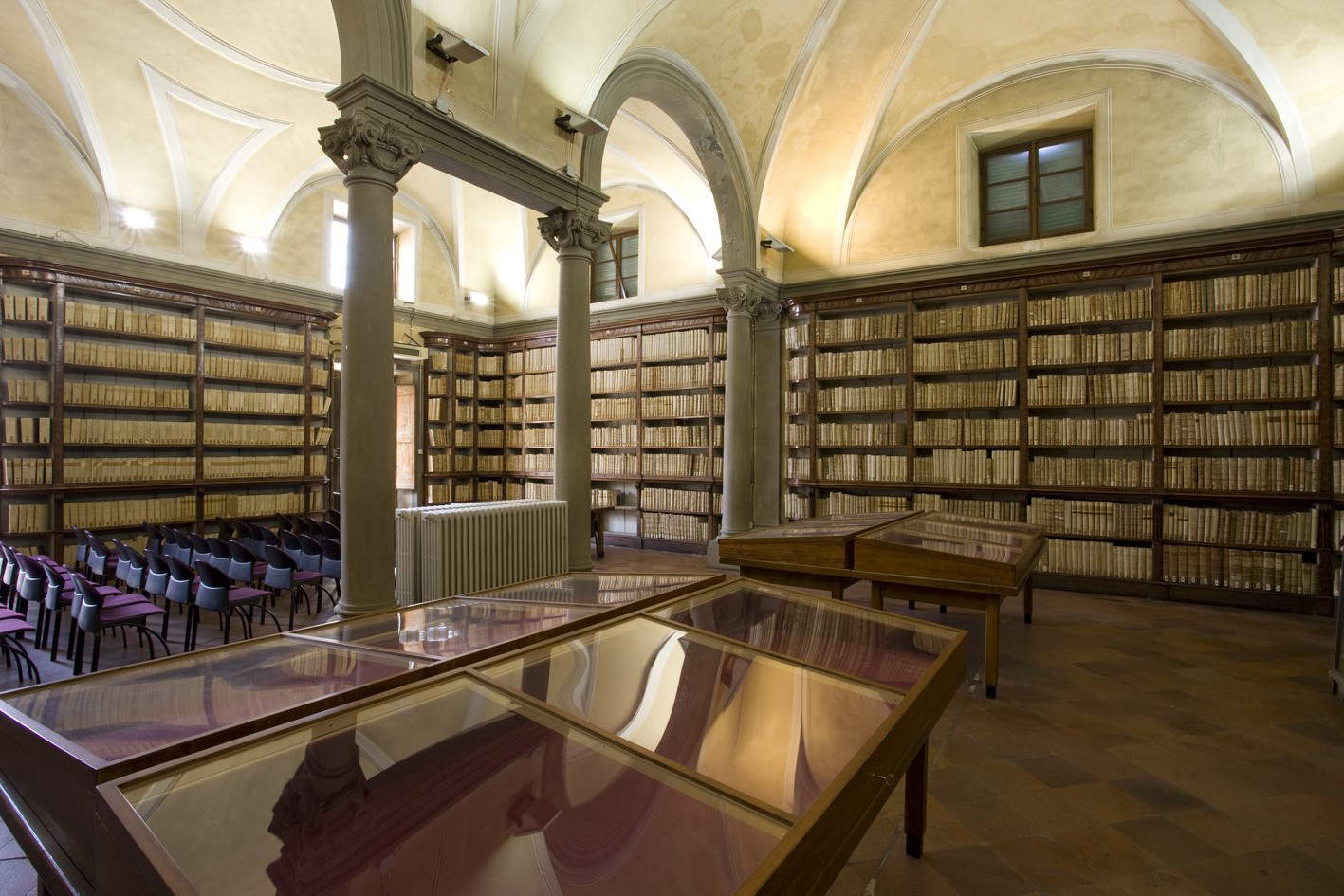

His interests, however, were mainly oriented in two directions: support for culture and support for the needy. The will, as anticipated, is useful for understanding the strong altruistic vocation that always characterized Puccini’s actions. He had no direct heirs, since, by choice, he decided not to marry, and named the orphanage in Pistoia as his universal heir (“the inexorable insinuations of those who advised me to call another person to succeed me, avvegnachè I have always despised the nobility of birth, appreciating only the nobility of actions, and I call myself fortunate to stop and assign my faculty in work that will bear fruit to the country, instead of it being dispersed by some successor in vices, cowardice and insolence.”) In the will, Puccini then arranged for his palace in downtown Pistoia to be used as the new home of the orphanage, heedless of any complaints from “those who do nothing for everything to blame” who might say “such a magnificent palace does not suit an orphanage.” Again, in the document Puccini also laid down the lines for the economic administration of the orphanage, to be managed with the annuities he made available. Among other wishes, Puccini left to the Forteguerri Library his two book collections plus one hundred liras per year for the purchase of books, established a fund to finance thirty-six free stays per year at the Montecatini spa to be given to the sick, and an additional fund (“with the annual surpluses of my Patrimony”) to be allocated to the city to meet needs in case of famine (in case of famine so severe that the funds of the annual surpluses were exhausted, Puccini stipulated that the other charitable works arranged should cease: “many,” the will reads, “will not like this disposition of mine, but he it is now impossible for one alone to remedy the misery of all; if those who disapprove of it are rich, let them remedy of their own my lack; if they are not, let them urge the rich to come to the aid of this Beneficenza Cittadina.”) Finally, on the funeral chapter, Puccini stipulated that once the funeral was over, a speech should be made summarizing the principles that in fact guided his entire activity: “let the bystanders be reminded that Beneficence to the Fatherland is the obligation of the Christian and that it is the duty of a Citizen, and that the rich are but Administrators of the Poor, and must with their wealth help industry and national education.”

His activities as a patron and philanthropist were based at his residence, the 18th-century Villa di Scornio in Pistoia, where he settled, once he returned from his Grand Tour, for the rest of his life, except leaving from time to time to go to Florence and frequent the Gabinetto Vieusseux, founded in 1819 by Giovanni Pietro Vieusseux (a friend of Puccini’s) as a salon where it was possible to read magazines from all parts of Europe and to which the Gabinetto subscribed (Puccini was a regular visitor). Soon the Villa di Scornio became the center of Pistoia’s cultural and political life in those years: many of the most important Italian and international personalities of the time were hosted here (Giacomo Leopardi, Pietro Giordani, Massimo D’Azeglio, Vincenzo Gioberti, Niccolò Tommaseo, Gino Capponi, and Enrico Mayer can be counted among them). Puccini, from a very young age, had shown great care for the family home: as early as 1820, in fact, on his initiative, his rooms were made to be decorated with images of the great Italians of the past and with those of the heroes of freedom. Later he would also have what were once the stables of the villa (built by his ancestors in the 18th century) transformed into large halls frescoed by distinguished painters of the time, such as Giuseppe Bezzuoli, one of the most distinguished Italian artists of the early 19th century (Bezzuoli also executed the portrait of Niccolò Puccini), Luigi Sabatelli, Gaspare Martellini, and Nicola Cianfanelli. It was Puccini himself who dictated the iconographic program: the large Sala delle Muse thus housed frescoes dedicated to the great artists of the Renaissance (Raphael, Michelangelo, Cellini, and Andrea del Sarto), whose memory the patron intended to honor.

Then, in 1824, having become the family’s sole heir, he invested considerable resources in enlarging the Scornio park, which surrounded the villa: by the time of his death it had become a green expanse of 123 hectares. He had it laid out as a romantic garden, according to the taste of the time (so there are reconstructions of medieval and classical buildings, water features, paths leading along intricate groves), also having monuments dedicated to great figures of Italian culture and science installed, with even a few international presences. In 1845, moreover, Puccini had a guide to the Puccini Garden Monuments published to which literary figures such as Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi, Niccolò Tommaseo and Raffaello Lambruschini contributed. Some of the monuments have not survived, but we are left with several sculptures: Dante Alighieri, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Carlo Linneo, the two columns with busts of Raphael and Antonio Canova, and the hemicycle of Galileo Galilei. In addition, designed by architect Alessandro Gherardesca, the “Pantheon of the illustrious men” was erected there, a neoclassical temple that was to enrich the facilities of the park (which, moreover, was also modernly equipped with cafes, restaurants and guest quarters: in fact, from 1830 the park had been open to the public).

The park, starting in 1841, hosted a particular “festival,” if you want to call it that using an anachronism, invented by Niccolò Puccini, namely the Festa delle Spighe, a fair that lasted three days and which, according to the accounts of the time, saw a first day devoted to religious celebrations and generally to rallies and public meetings, the second to competitions among peasants (the main purpose of the festival was in fact to encourage the modernization of the methods of ’agriculture) and the livestock show, and finally the third was devoted to the schools founded by Puccini (and based in the same park as the villa), with students being called upon to give essays of what they had learned during the year. The festival represented, however, as historian Marco Manfredi has noted, the most obvious sign of the shift in Puccini’s political convictions to much more moderate positions than those he had held in his youth, as it was “steeped in devotional references and largely open to priests, in the ’intent on extolling the usefulness of religion for the maintenance of social and political order,” and thus exemplifying a softening of “the overtly secular moods previously conditioned by the influence of figures such as Pietro Giordani or [Giovanni Battista] Niccolini.” The Festa delle Spighe continued until 1846, when it was discontinued due to changing political conditions: Puccini, we read in a 1908 article, had “remarked that political strife had diverted youth from the arts of peace and that tranquility without which agriculture cannot flourish.” It has, however, been revived in recent times: in 2022, in fact, an eponymous “Festa delle Spighe” inspired by the one held for six years by the great Pistoiese philanthropist was organized in the very park that was once Villa Puccini.

Today, the park is no longer what it was in Niccolò Puccini’s time, because after his passing not everything went as he had planned. As mentioned, the patron had left all his possessions to the Pistoia orphanage, but his legitimate heirs contested the will, and a court case ensued that led to the auction of the villa and park in 1862. Two years later, the estate was divided among thirty different owners, with the result that the park irrevocably changed its physiognomy and the buildings that were part of it, such as the castle, the Gothic temple, and the Pantheon, were put to the most disparate uses (the Pantheon for example even became a barn), several monuments were removed, and in the following years many plots were abandoned and left in decay. The coup de grace came in the 1960s, when building speculation permanently altered the park. In any case, the park, “a source in its time of inspiration for the park of Celle in Santomato,” as we read on the site (today in fact the garden has come back to life precisely under the name “Puccini Park”), “especially in the part privately owned by Dr. Guglielmo Bonacchi, has managed to avoid the fate of so many other historical parks, alive only in literary memories, and has thus been able to enjoy the recovery of its own compositional language, first plant, then architectural. The same can be said for the restoration work of the Pantheon, on the individual initiative of the heir Guglielmo Bonacchi, aimed at recovering in a historical-philological form the structures and decorations of the important neoclassical building, within the limits of a conservative restitution mindful of the need for consolidation and modern comfort. Thus was recovered in its structural essentiality a neoclassicism veined with Palladianism with vibrant sensibility of moldings and proportions.” Unfortunately, it has not been possible to recover “in its totality the fabric of busts, cippi, monuments that inside and out [...] contributed to exalt the romantic memory of the past and the ’sublime’ ideal of beauty for the expansion of individual life into the larger national sphere.” The rearrangement of the park also gave prominence to the paths and monuments. In this way, the dream of the generous patron of studies and the arts lives on, and the garden has once again come to offer itself as a “dwelling-refuge of dreamlike distances and cosmic sensations.”

What has become of the villa’s furnishings, however, and of the villa itself? The part of the art collection that was not sold after Niccolò Puccini’s death came to the Museo Civico d’Arte Antica in Pistoia in 1914: today it is on display on the museum’s top floor. The villa, together with a part of the park (the one that includes the large lake and the island with the ruins of the temple of Pythagoras) also became the property of the Municipality of Pistoia, and in the present day it continues the educational vocation pursued by Niccolò Puccini: in fact, it is home to the “Teodulo Mabellini” School of Music and Dance and the Foundation Accademia di Musica Italiana per Organo. In part, then, the soul of the great benefactor continues to survive within the walls of his home.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.