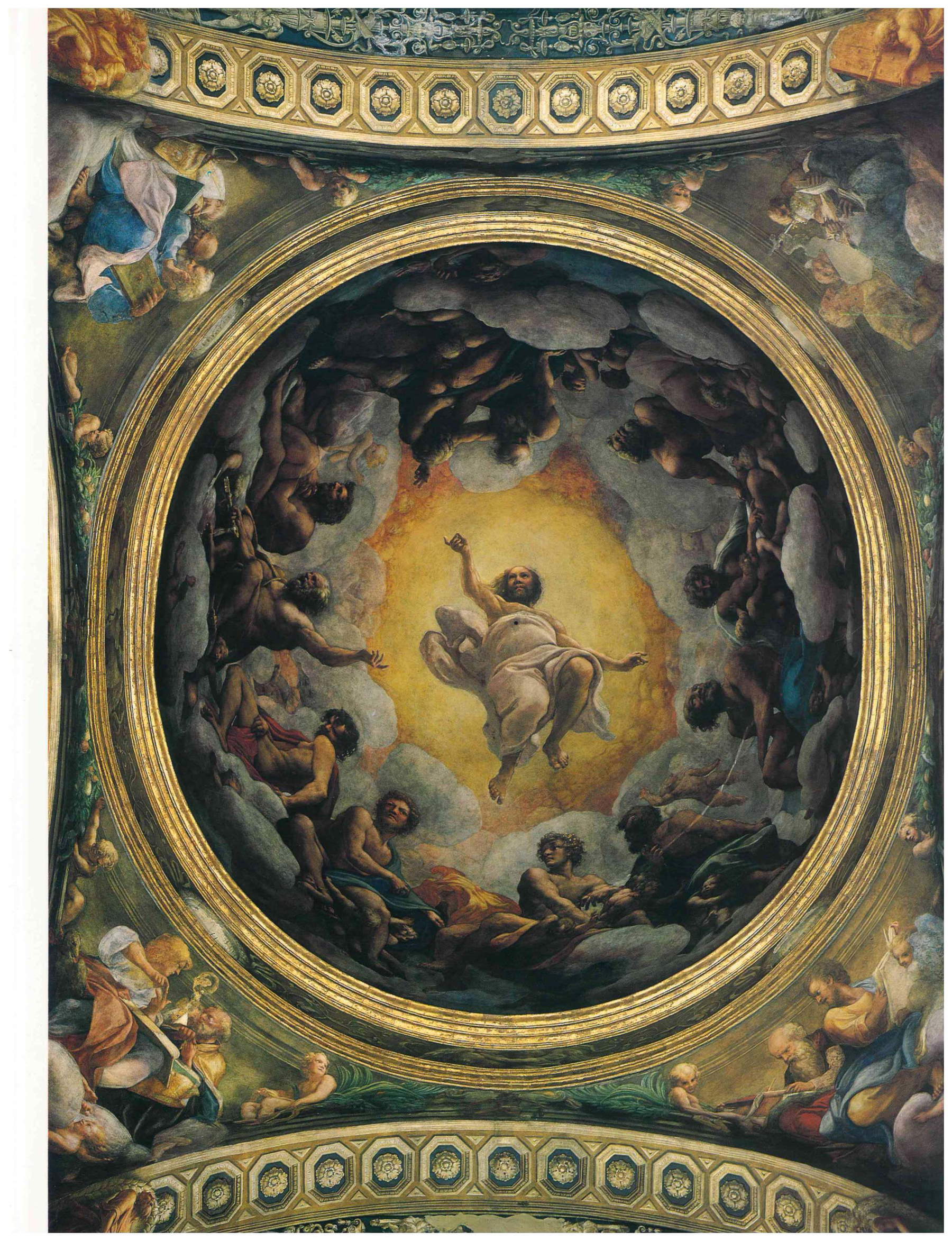

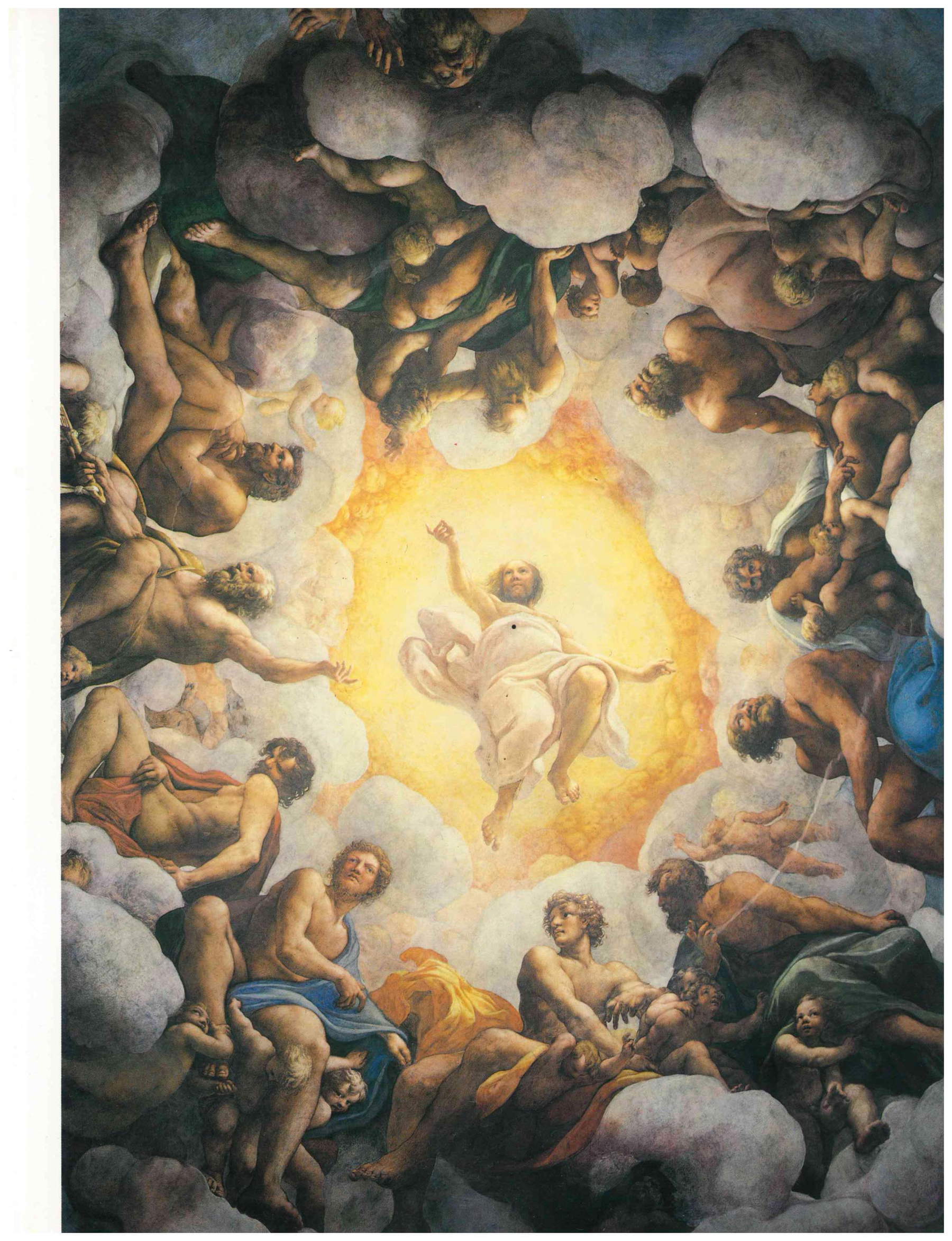

More on Correggio's frescoes in the dome of the abbey church of San Giovanni in Parma

As already written in the December 31, 2023issue of “Finestre sull’Arte,” in the 1980s Parma was becoming a small restoration capital in Italy. The then Vicar General of the Diocese, Monsignor Franco Grisenti, a priest with great organizational skills (to him we owe the decades-long and prescient maintenance of a conspicuous part of the churches and religious buildings of the city and province), following an advice from the president of the Pontifical Commission for Sacred Art in Italy, Monsignor Giovanni Fallani, had managed to bring two former directors of the Central Institute for Restoration (= Icr), Pasquale Rotondi and Giovanni Urbani, to Parma. The problem Monsignor Grisenti was trying to remedy through Rotondi and Urbani was the proprietary attitude the local Soprintendenza and the local University had toward the Church’s heritage. For a decade or so, in fact, a huge scaffold had been stationed in the presbytery of Parma Cathedral that was supposed to be used for the restoration of Correggio’s frescoes, but on which no one was climbing. A restoration that was supposed to be carried out in function of a messianic exhibition on the Emilian artist curated by the local University and financed by the City of Parma, but to be finally realized it would have to wait about thirty years and for the Superintendence to organize it in 2008: thirty years of controversy, bureaucratic blockages, mutual accusations and so on. But also deserted for a few years was the scaffolding that was to be used for the restoration of the west portal of the Baptistery, thus foreshadowing an affair not unlike the one taking place in the Duomo for the Correggio frescoes. Hence Monsignor Grisenti’s idea that the Church of Parma should exercise its right-duty as owner always, however, keeping its actions at an indisputable technical level. That assured by the consulting dio Rotondi and Urbani, in fact those who founded the science of heritage conservation in relation to the environment.

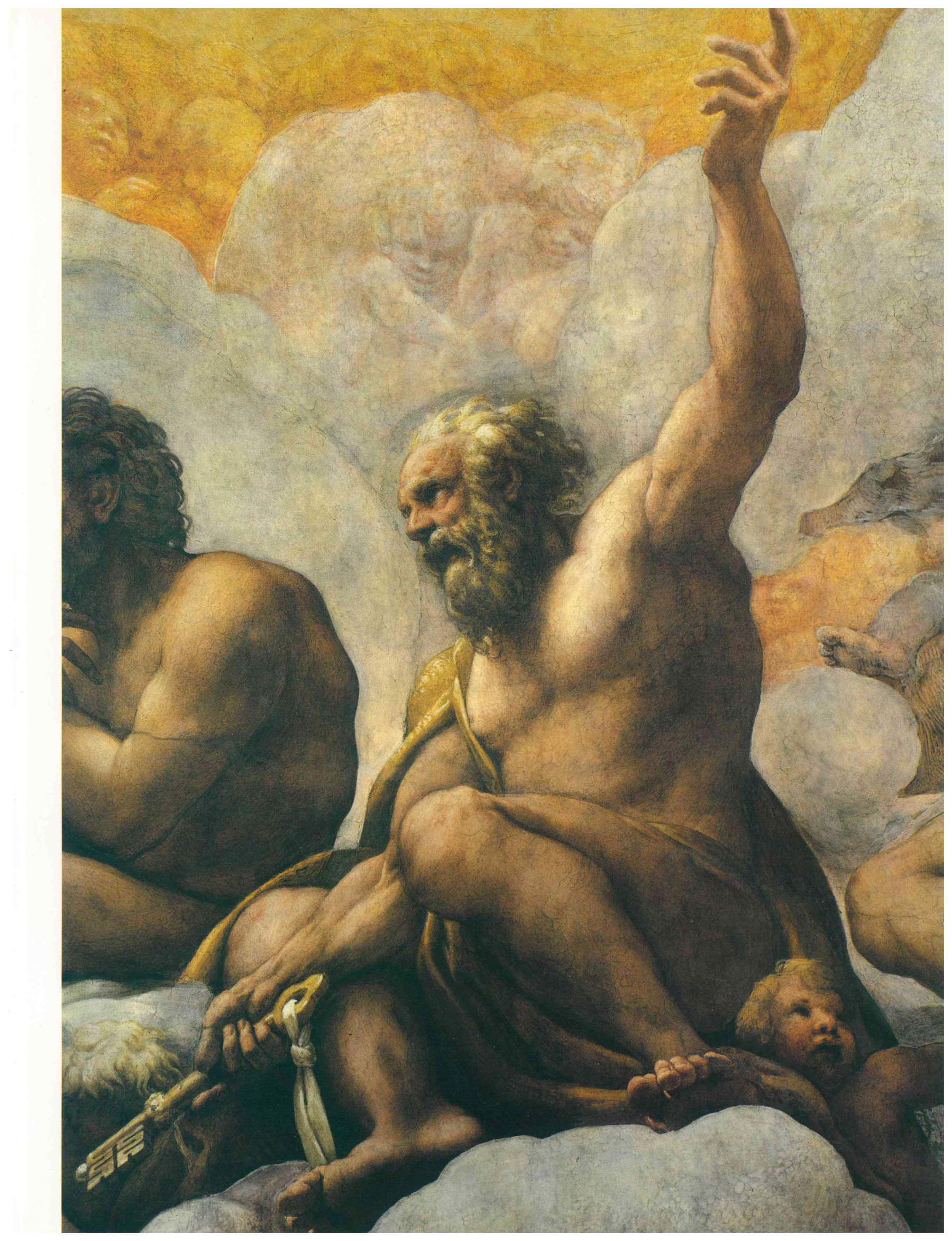

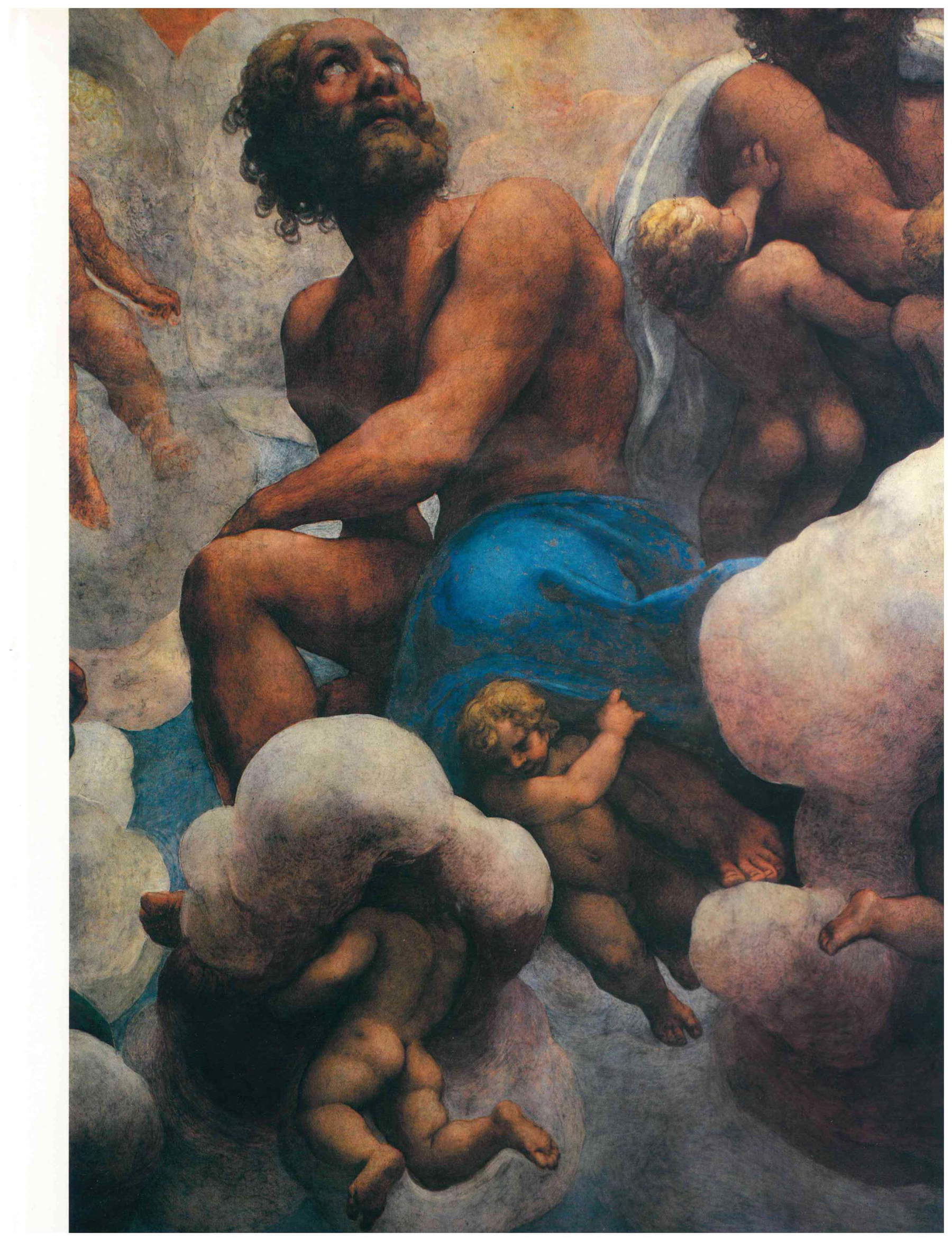

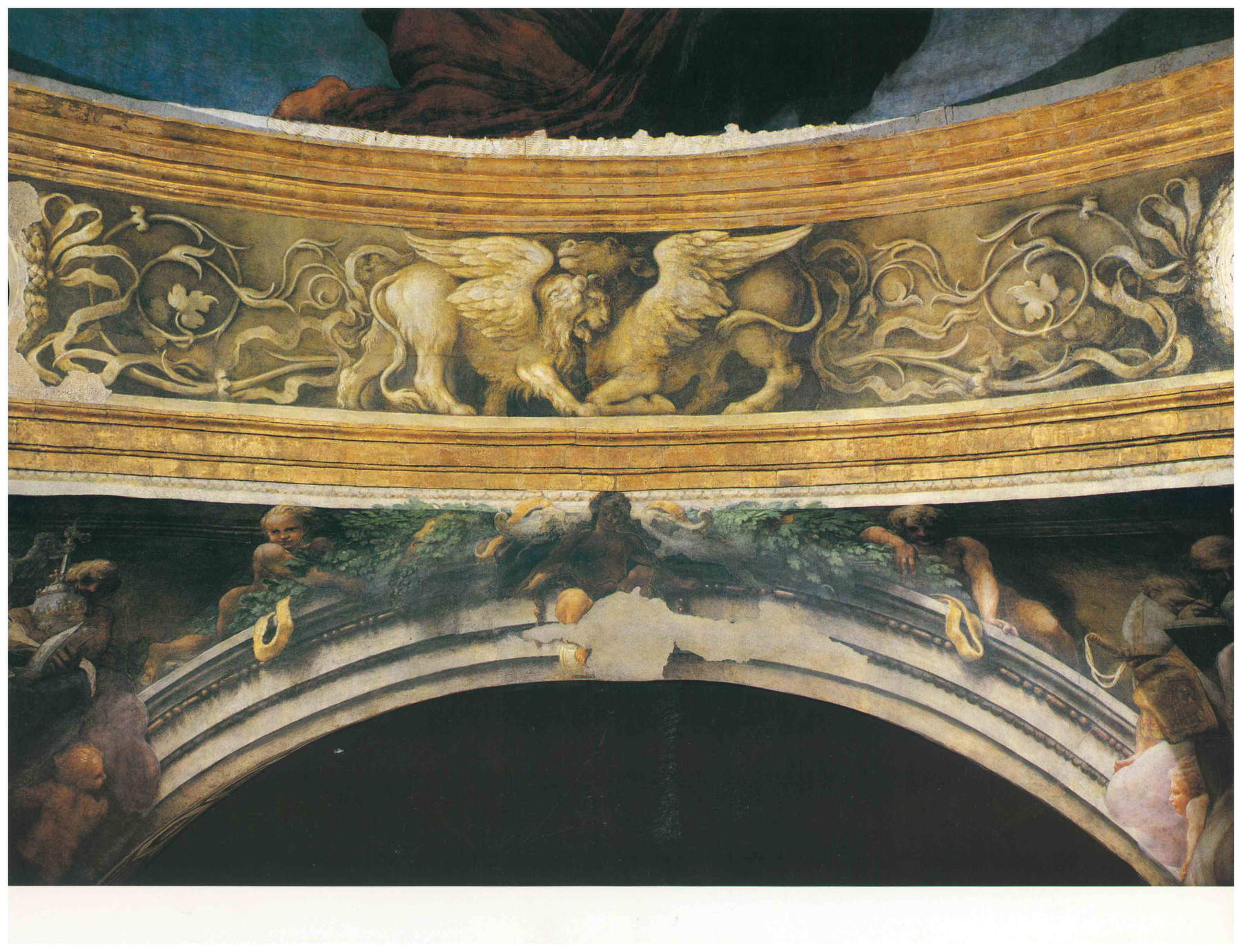

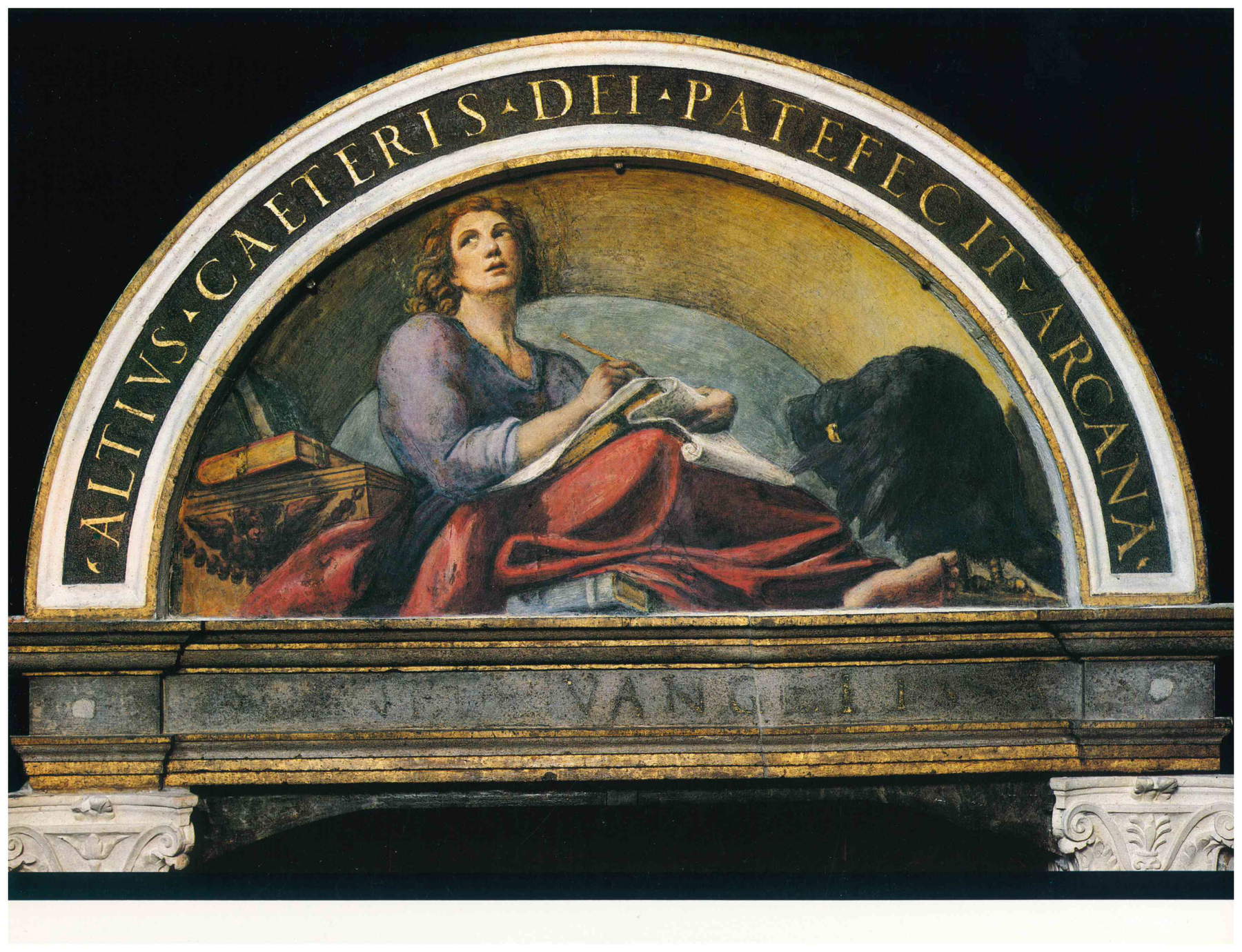

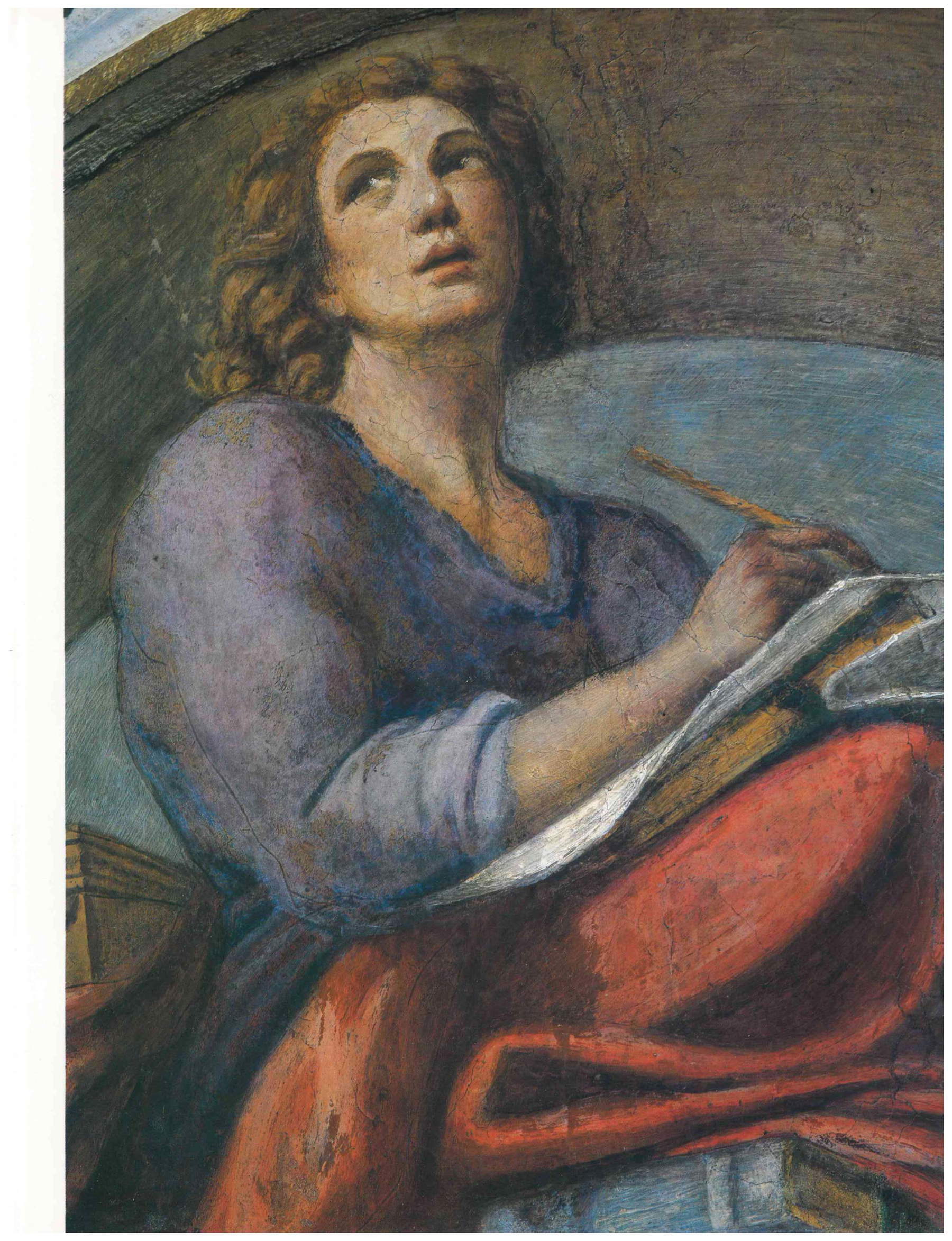

An extraordinary affair in many senses, this just said, which unwittingly gives rise to an important and entirely new cultural fact in the whole of Italy. Culture of institutional relations, administrative culture, and technical culture that convinces the local Cassa di Risparmio to finance the restoration of one of the most important monuments of the medieval West, the Antelamic Baptistery of Parma. And it will be the first intervention conducted in Italy on the basis of a restoration project defined with every precision in terms of time, methods and costs. An example of reliability in whose wake stands a young food industrialist, Marco Rosi, founder of “Parmacotto,” who in 1989 offered to finance the overhaul, in fact an extraordinary maintenance, of the restoration conducted some 40 years earlier of Correggio’s frescoes in the dome of the abbey church of San Giovanni. An intervention completed in a year, which was followed by a tour of the frescoes from the scaffolding that attracted about twenty thousand people. And here I think it should be said, about the fertility of what was happening in Parma, that two years later Rosi would finance, in Rome, the restoration of the frescoes and mosaics of one of the holiest, most mysterious and important monuments of our Middle Ages, the Sancta Sanctorum at the Lateran. An intervention conducted under the supervision of the then Director General of the Vatican Museums Carlo Pietrangeli, whose execution was followed almost daily by one of the great art historians of the 20th century, Federico Zeri. A restoration that half the world talked about and that made Rosi a historical figure of cultural patronage in the twentieth century.

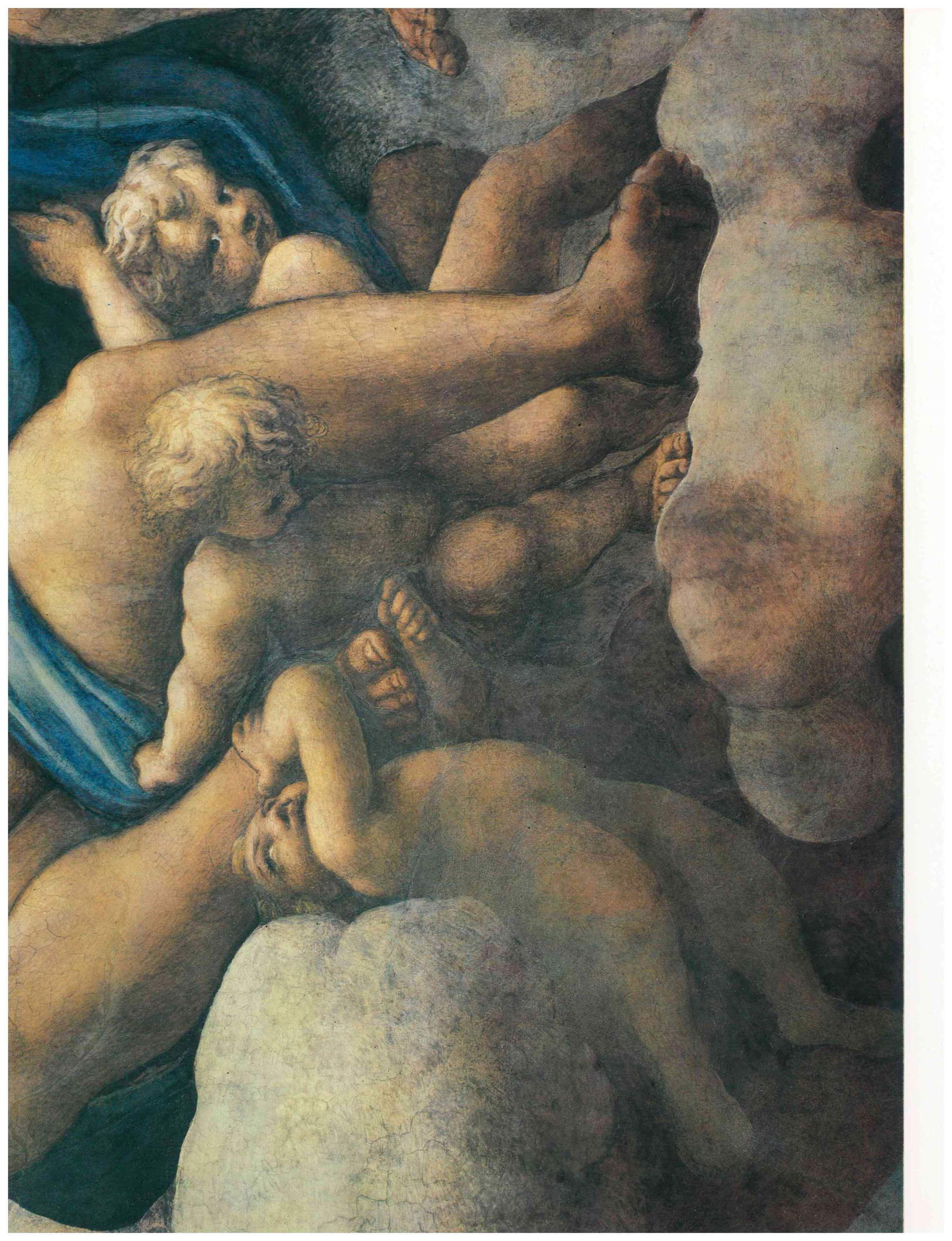

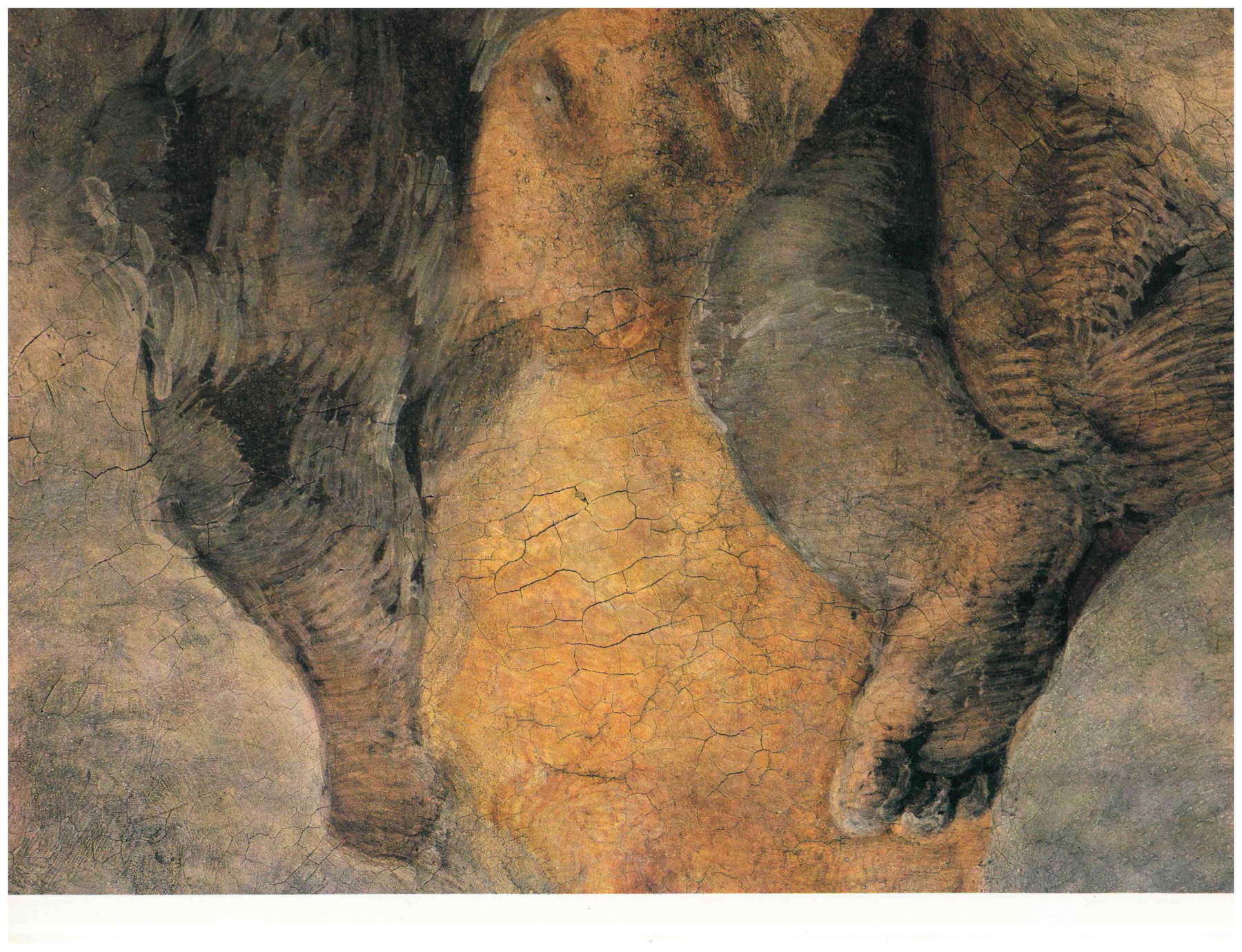

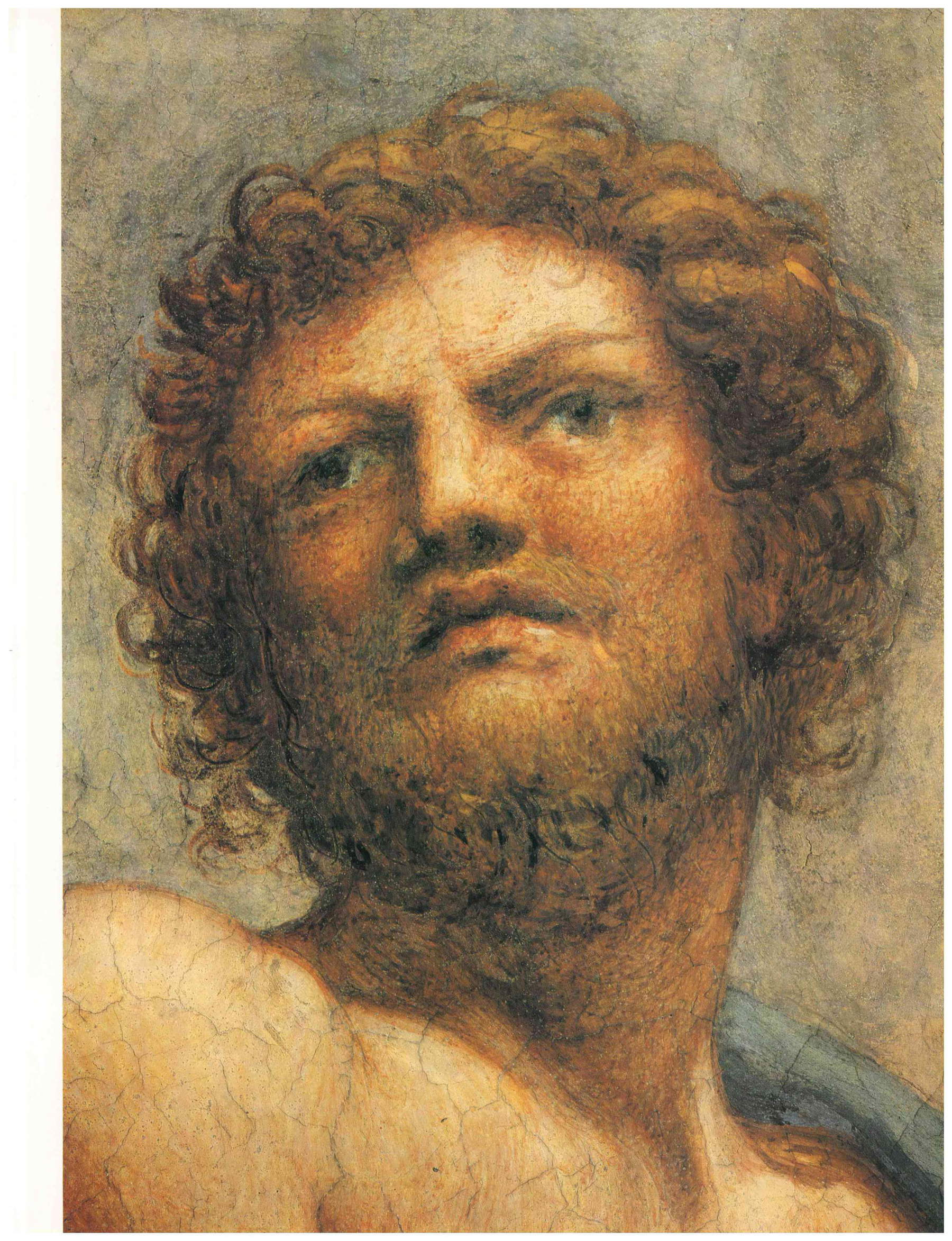

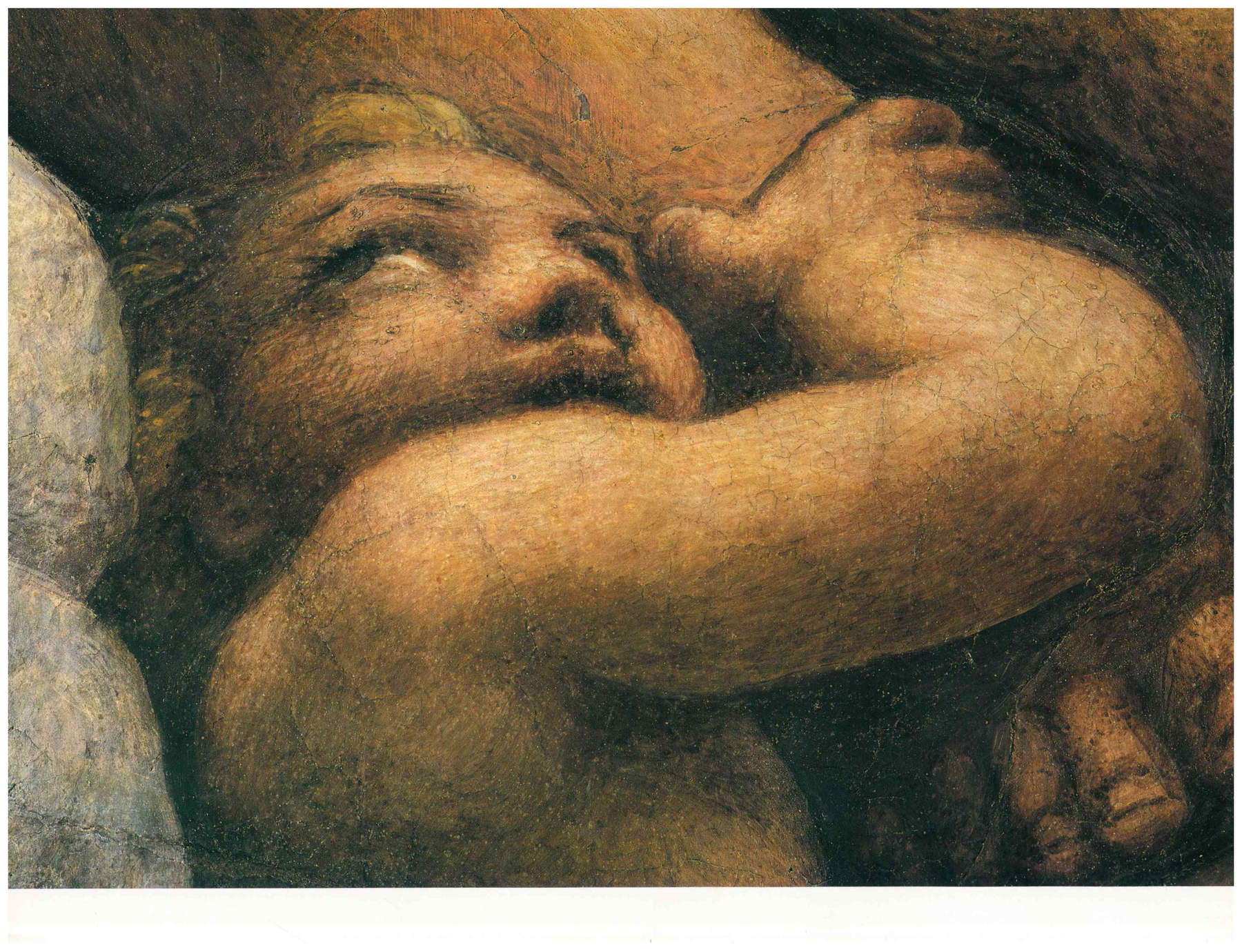

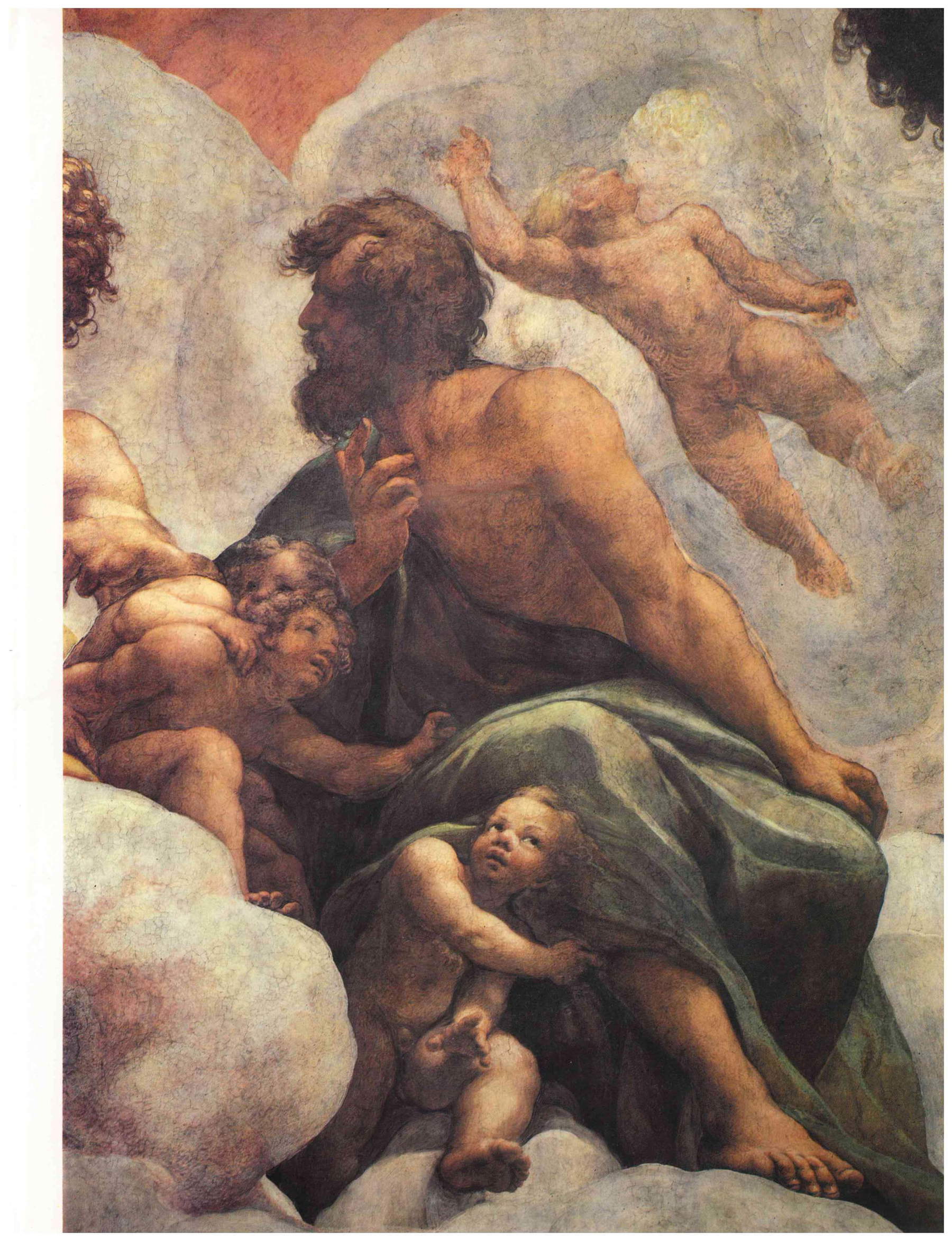

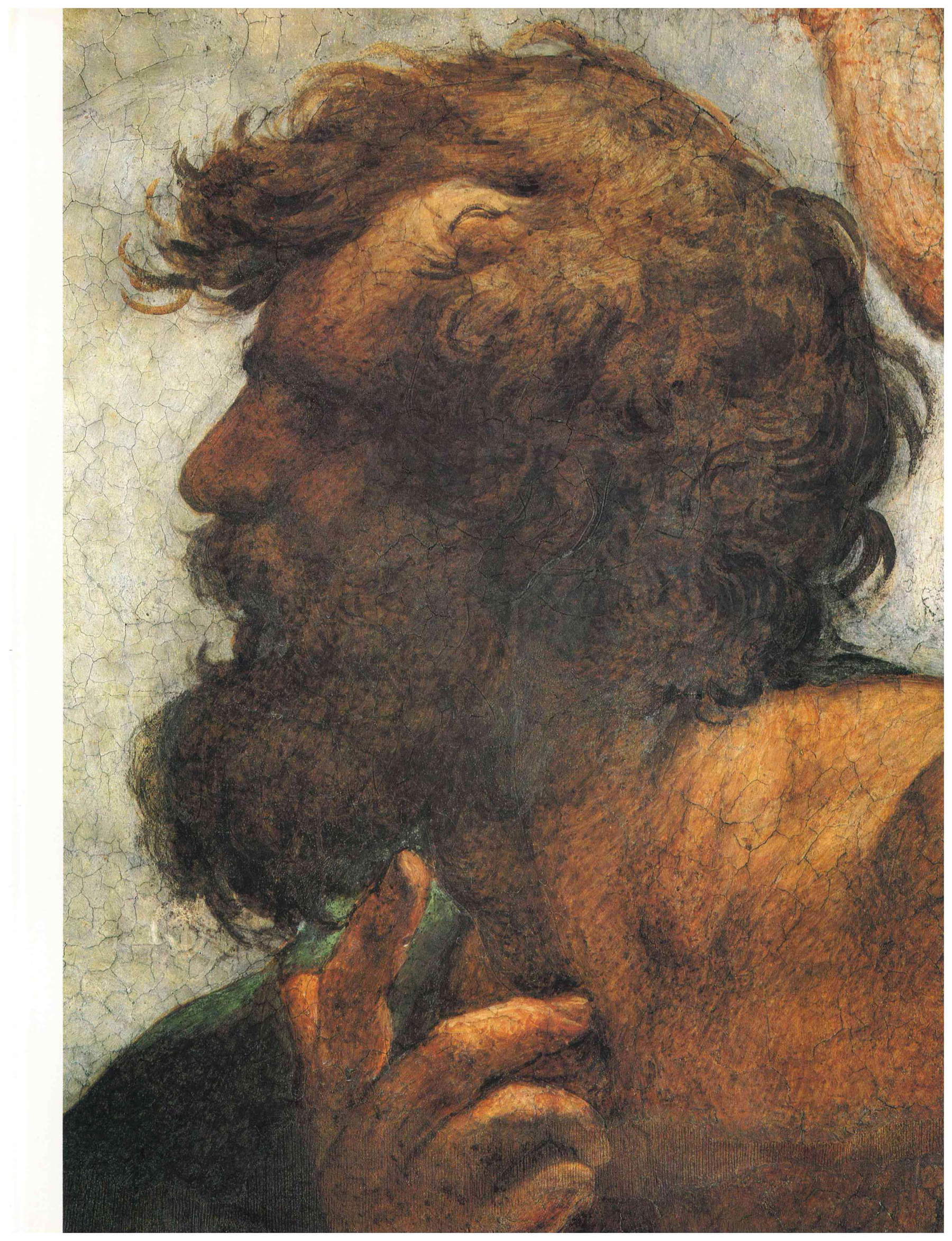

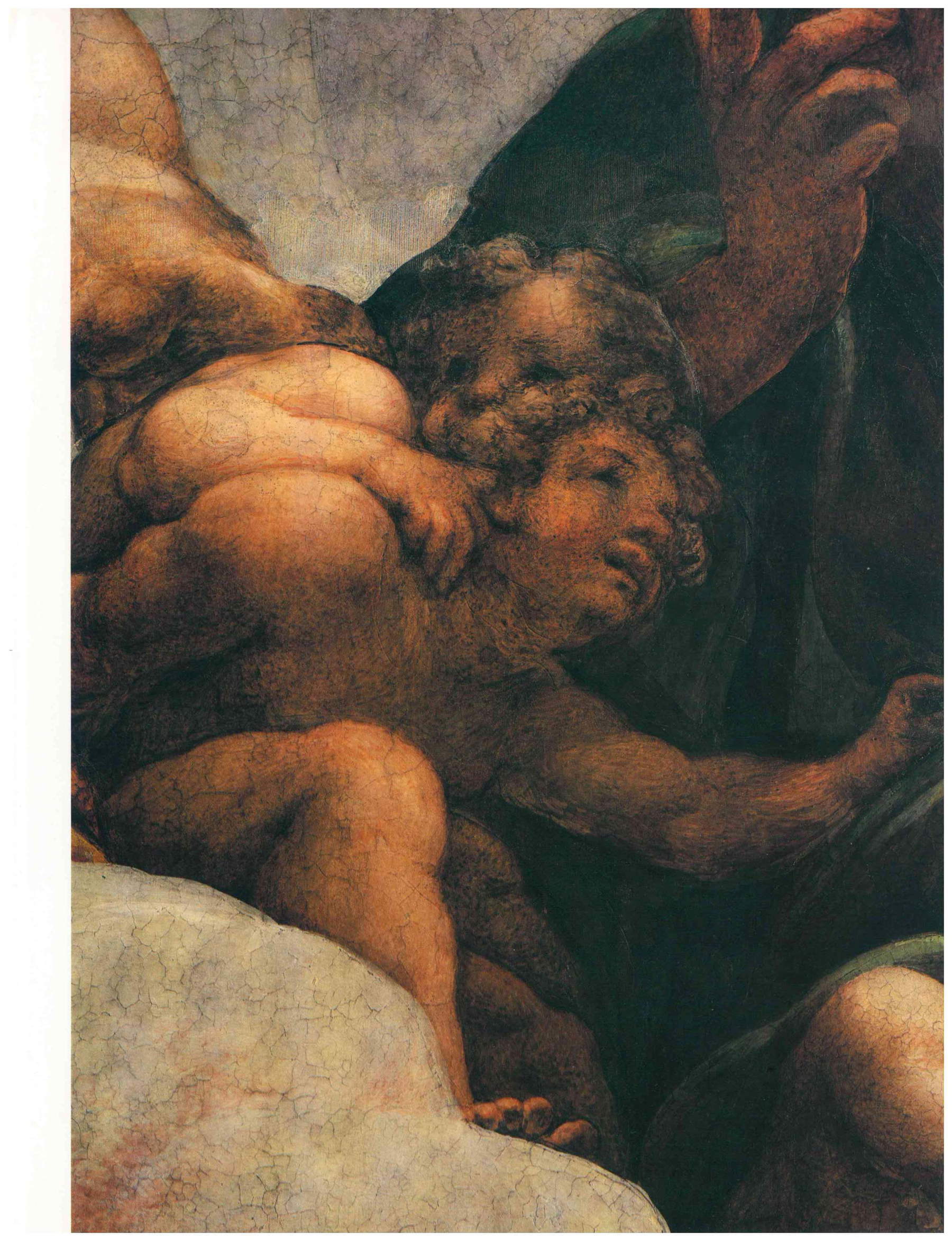

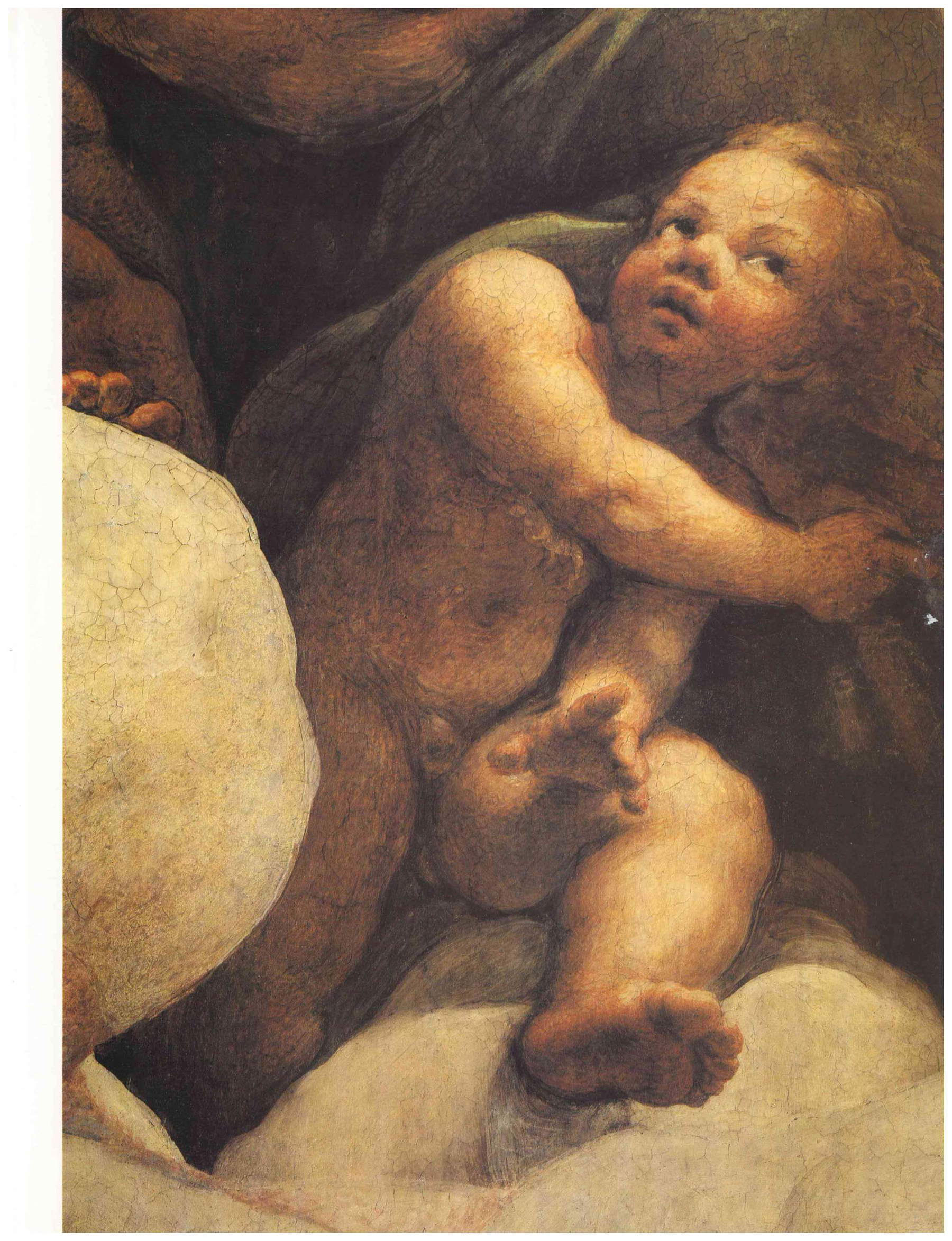

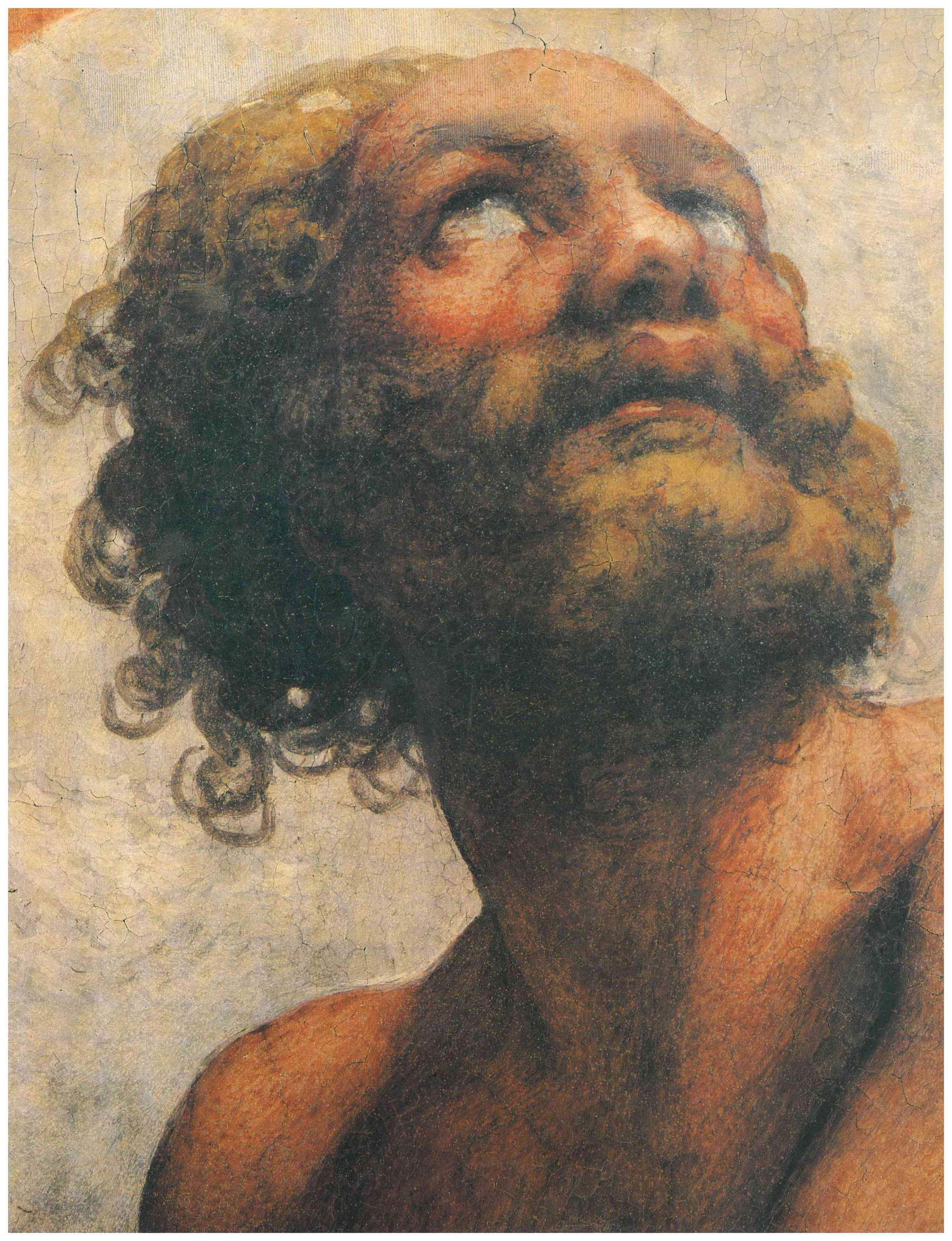

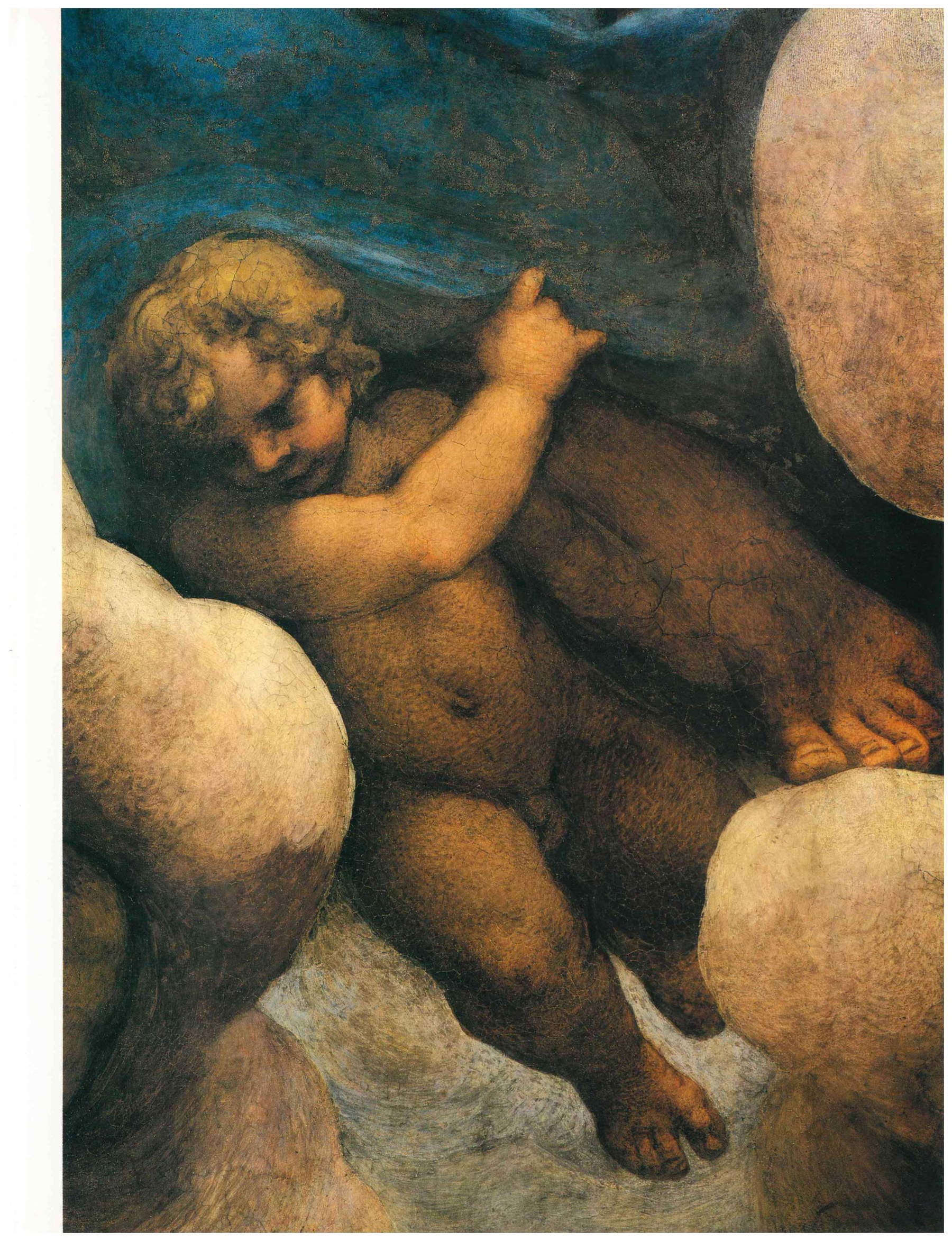

Actor in these restorations was the writer, (then) a young restorer trained in the international closed-number school of an Icr that was still an undisputed international point of reference, and who not long before had been commissioned to restore one of the most celebrated monuments of classical antiquity, the Trajan Column. It was a restoration that had put me in direct contact with the Scuola Normale of Pisa and with a celebrated archaeologist, Salvatore Settis, and two of his most brilliant students, Giovanni Agosti and Vincenzo Farinella, as well as with important civil servants, scholars and intellectuals. From the then superintendent of the Imperial Forums Adriano la Regina, to Antonio Giuliano, Bernard Andreae, Fausto Zevi, Alessandra Melucco, as well as those who as it were “came to visit the Column” such as, to name but a few of the many, Sylvia Ferino, Italo Calvino, Giuliano Briganti, Alberto Arbasino and Jacques Le Goff. And it was Agosti, returning to Correggio’s frescoes in the dome of San Giovanni, who proposed publishing them in an elegant gray silk slipcase and with “loose” full-page photos taken by one of the photographers of the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence, Luigi Artini, and to entrust the scholarly part of that task to a distinguished cultural historian, Francis Haskell, and to ask an eccentric novelist, Alberto Arbasino, to write a story in which the frescoes would be read in narrative rather than academic form. And it is the photos and texts that are published here, saving them from the oblivion to which they would otherwise have been destined.

While already in the December 31, 2023 issue does “Windows of Art” made downloadable the link to the short film in which Giuseppe Bertolucci asked his father Attilio to tell him about his relationship with the Correggio of Parma and also the same issue of the magazine in which I mentioned the senseless waste made of it all. A criminal affair that can be said about elsewhere.

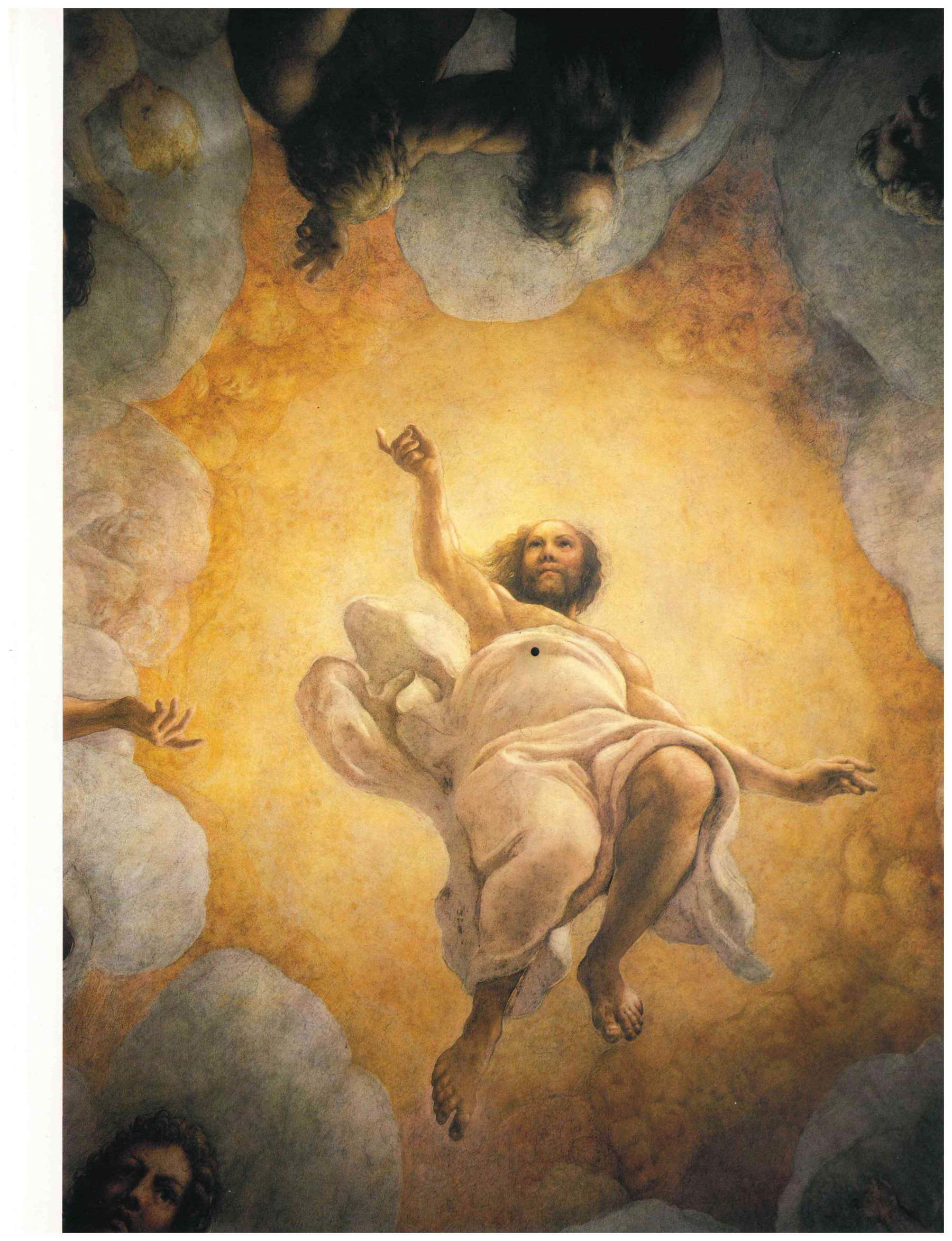

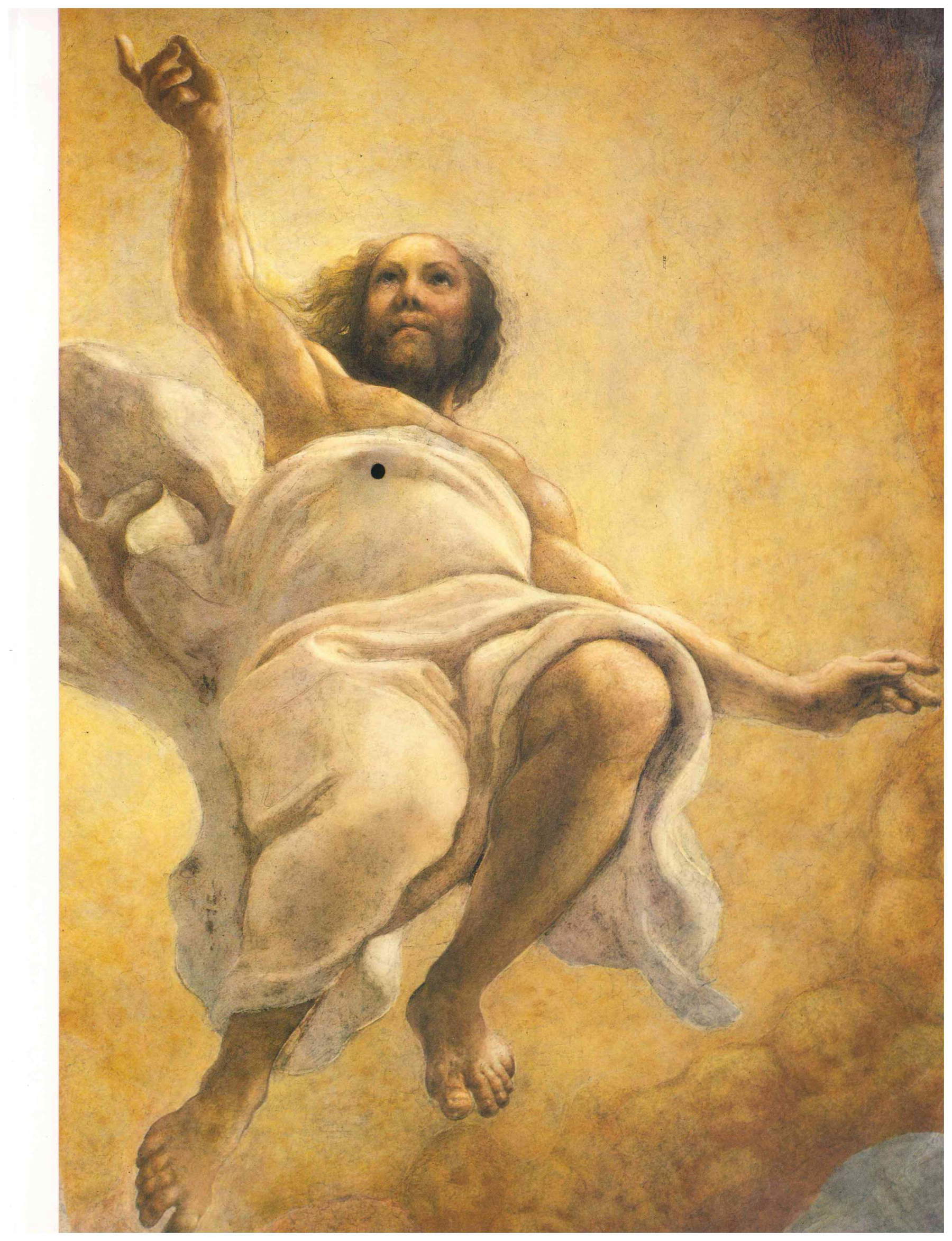

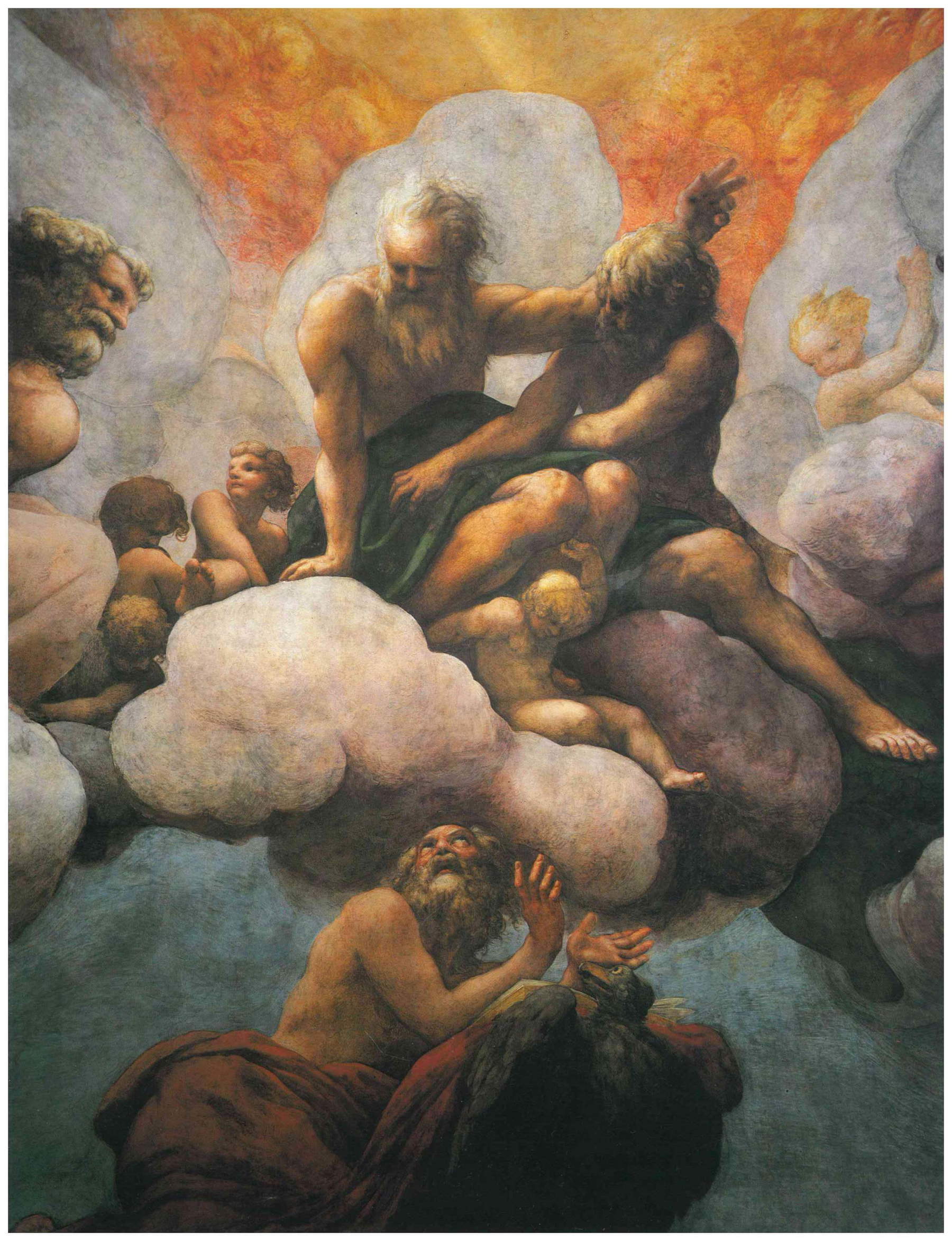

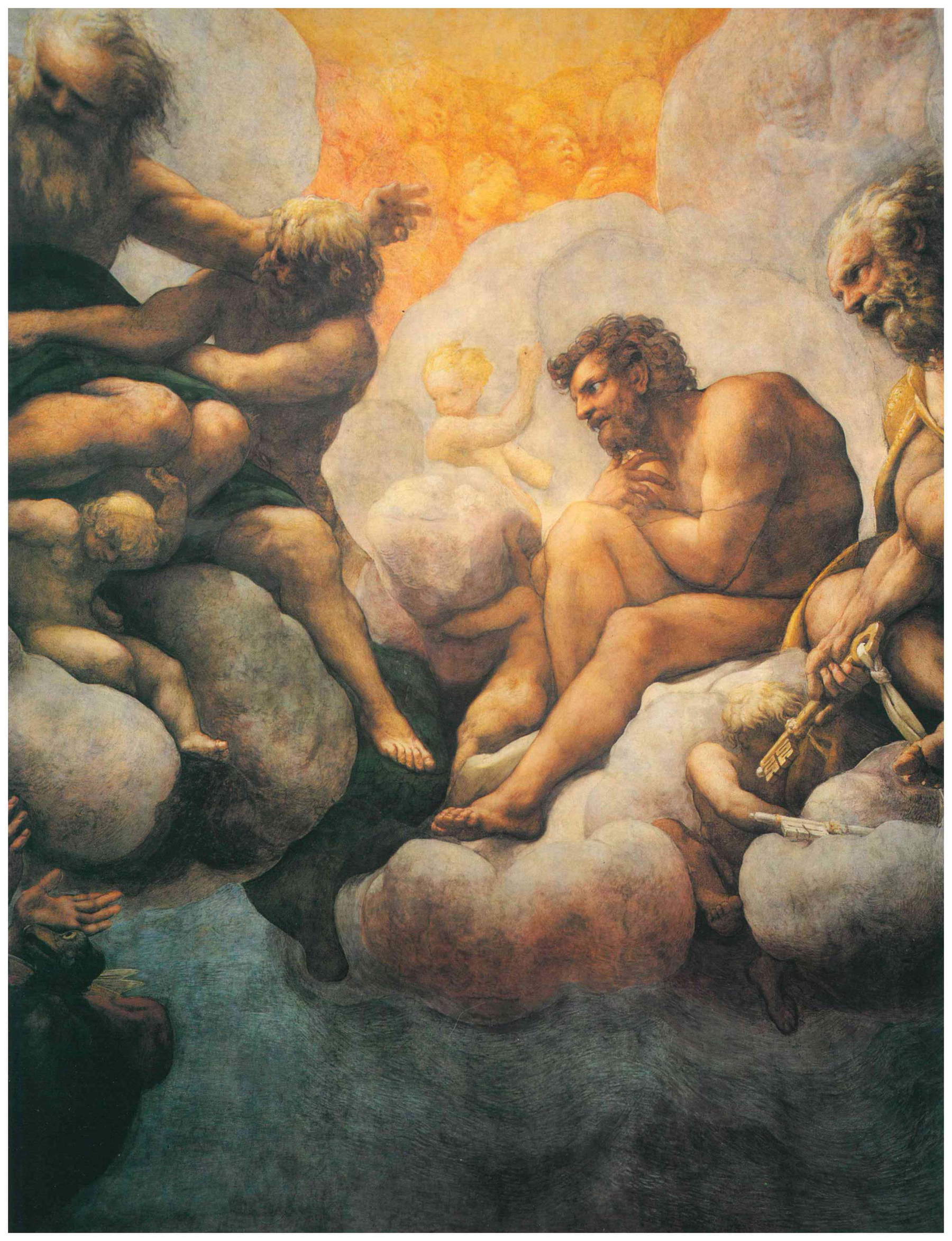

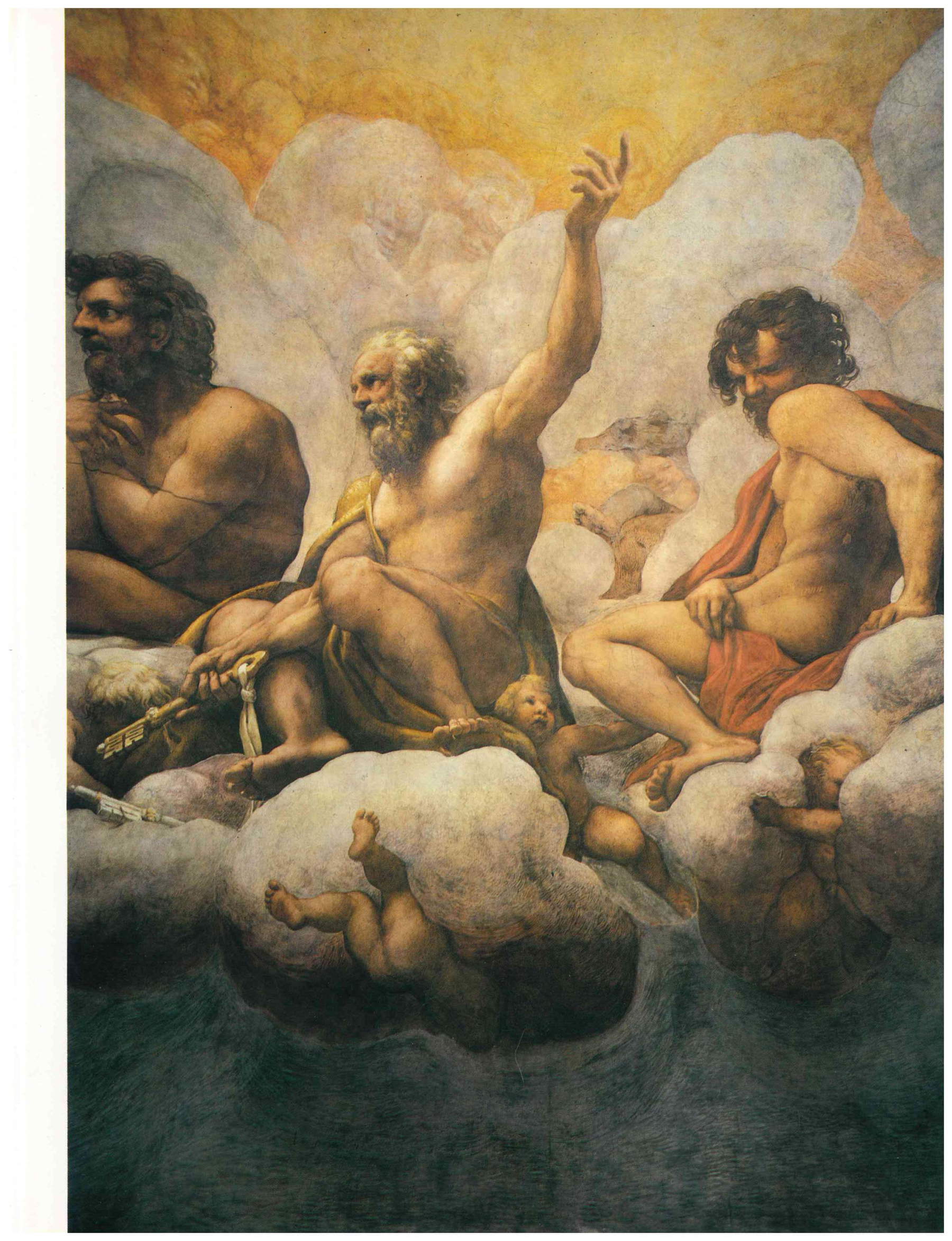

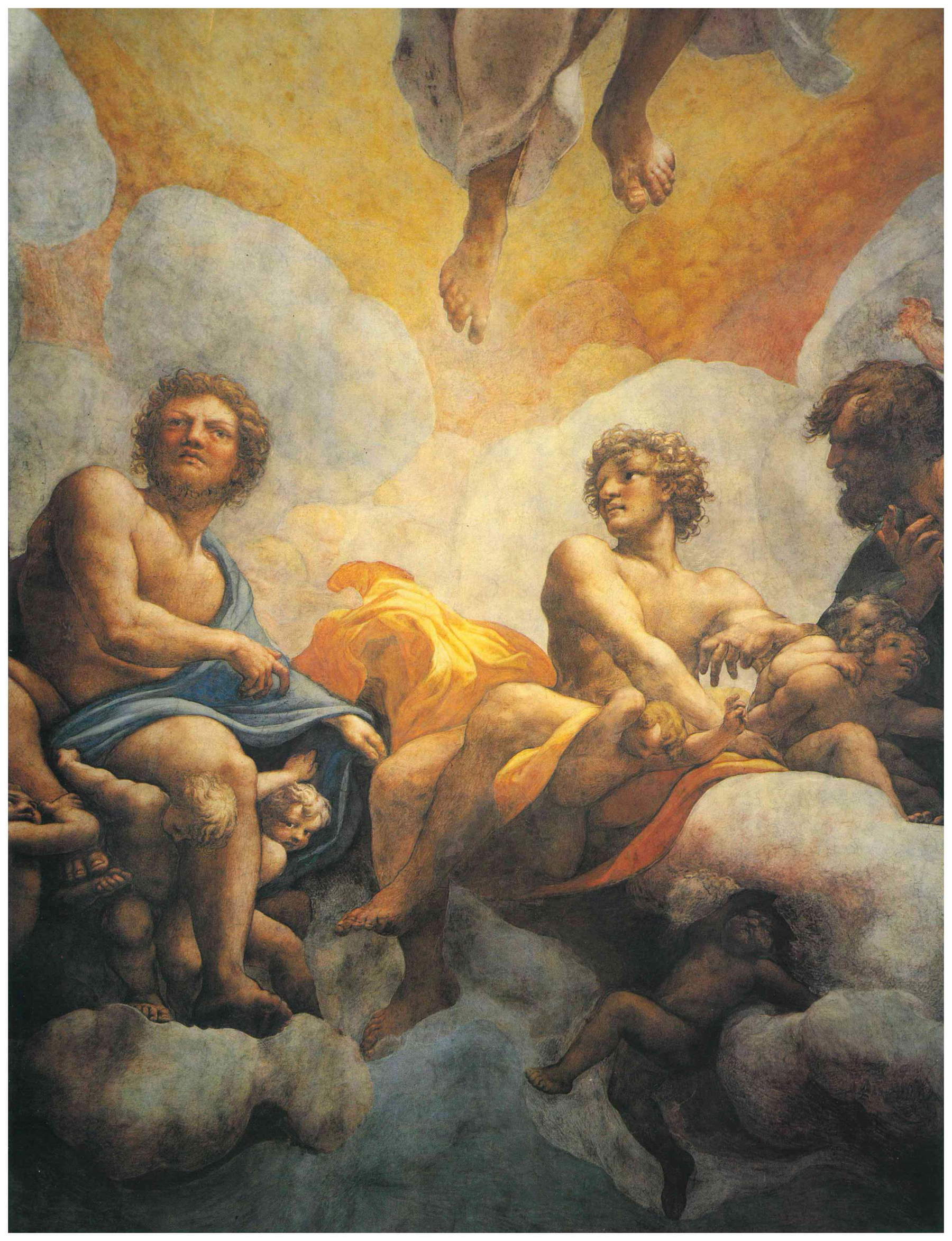

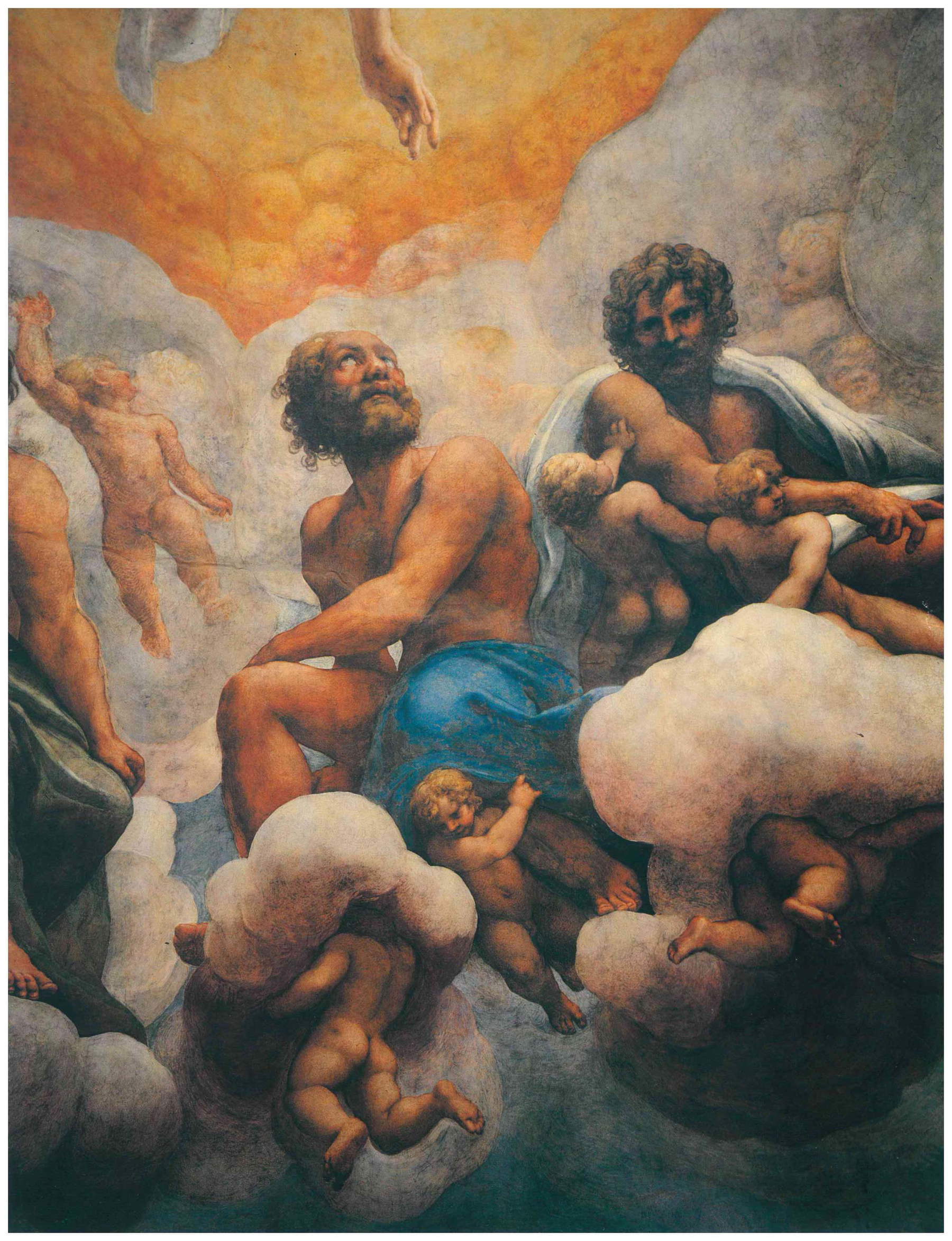

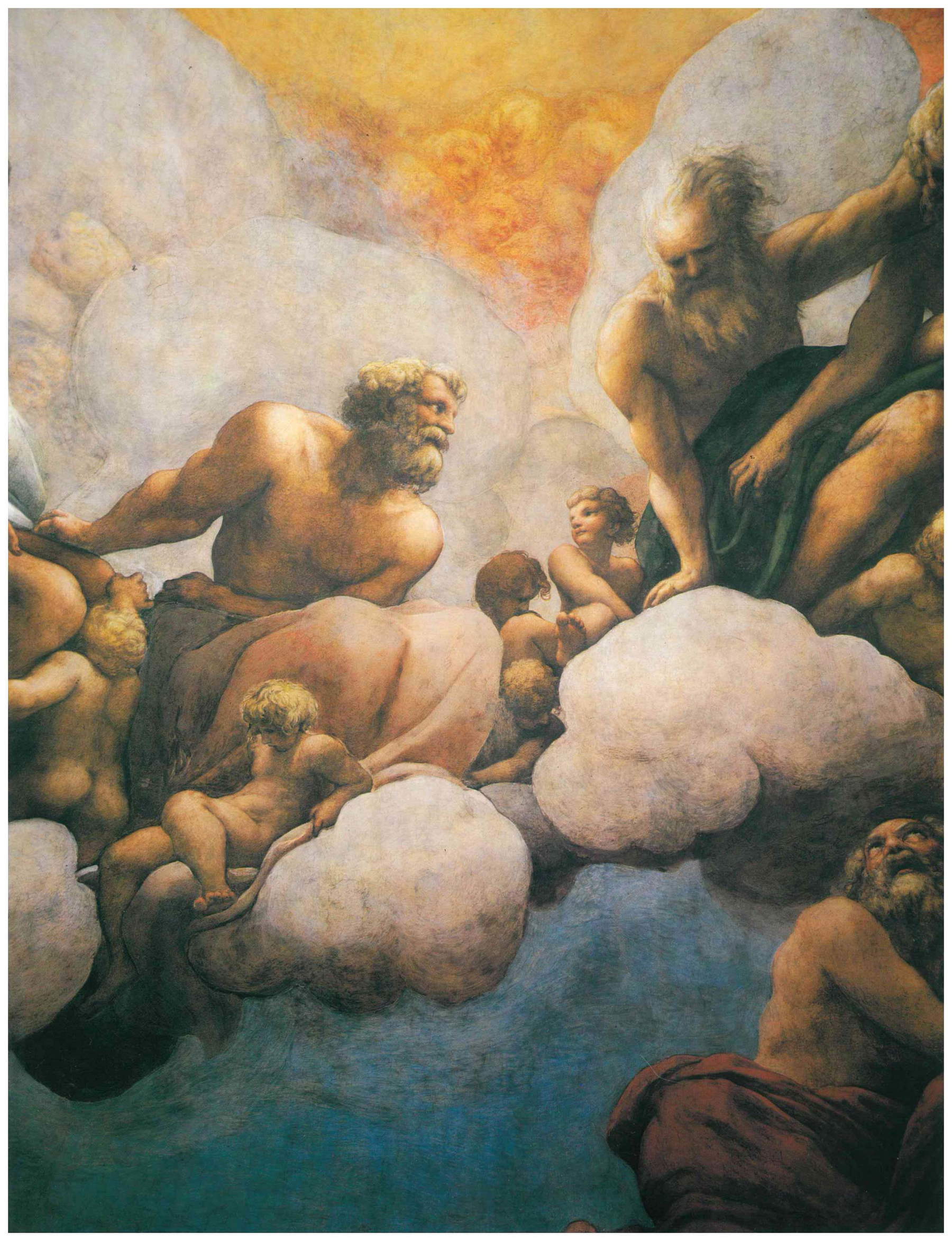

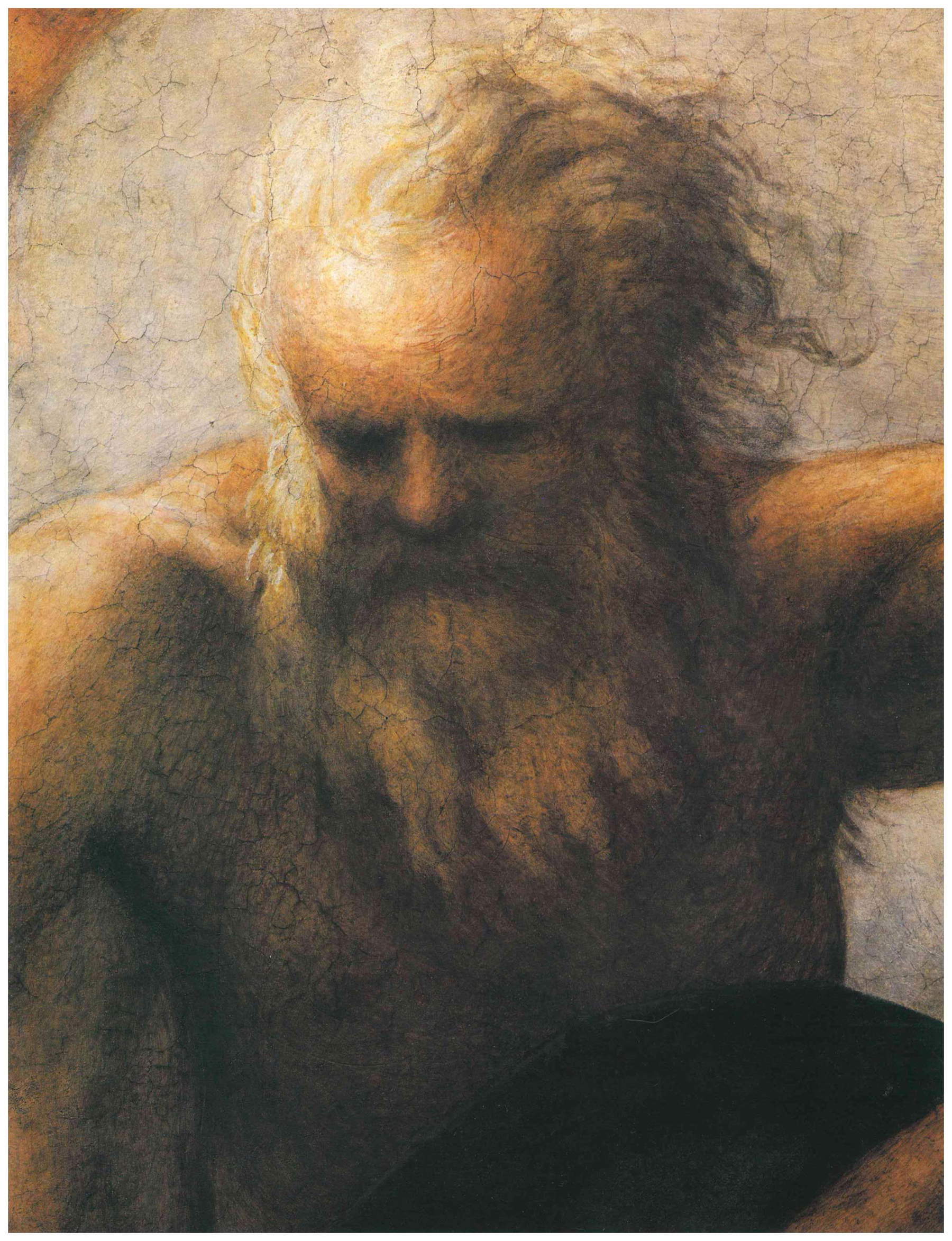

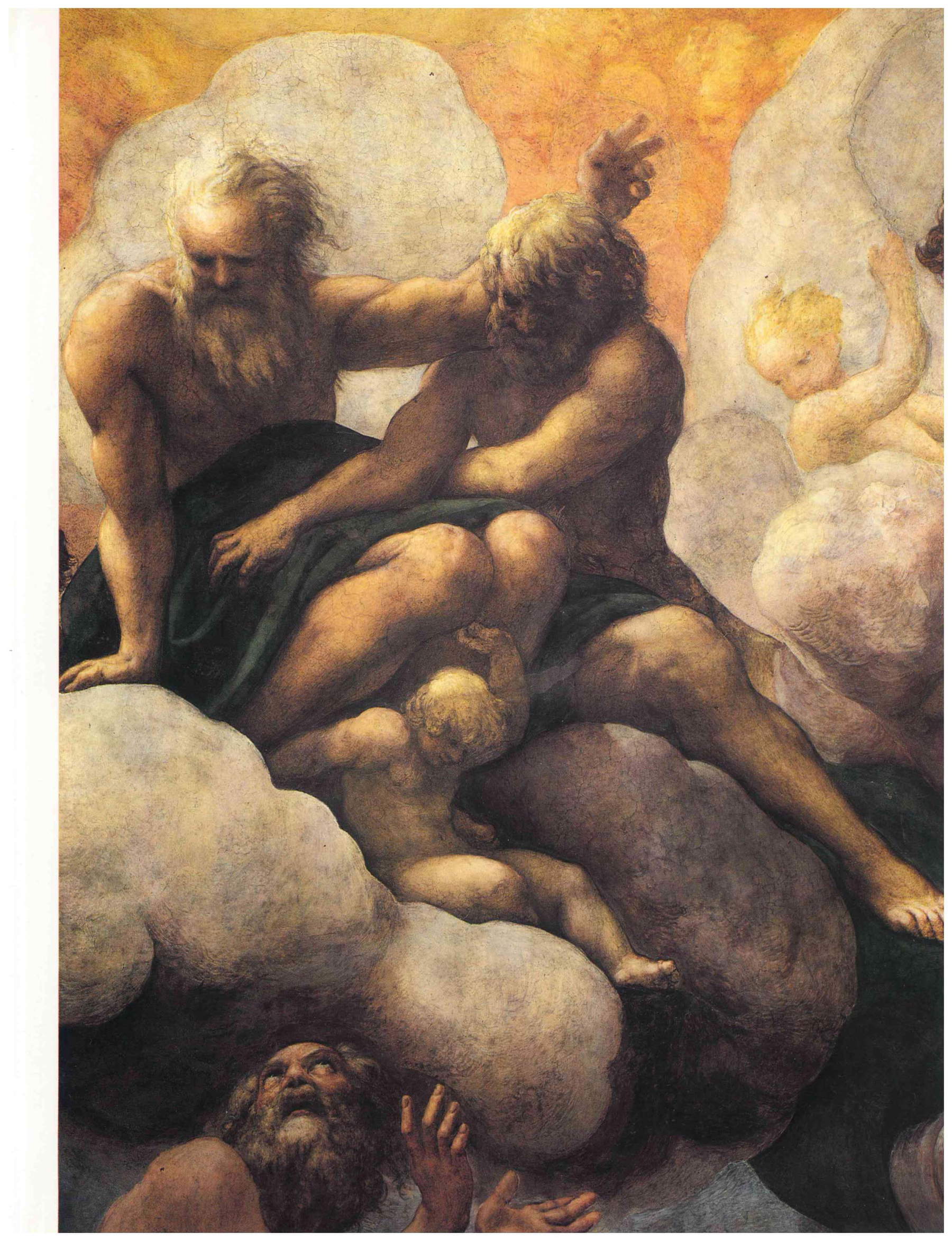

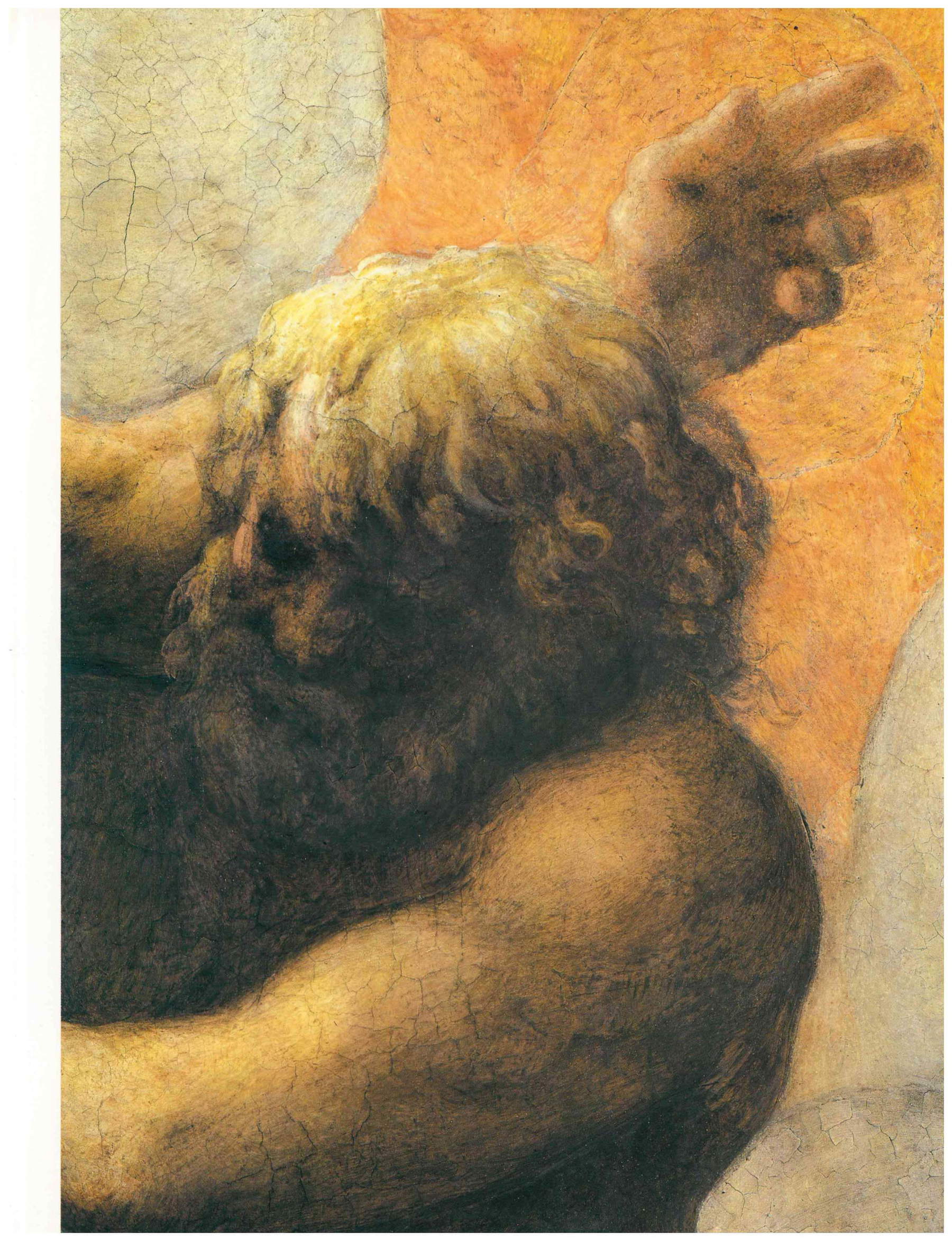

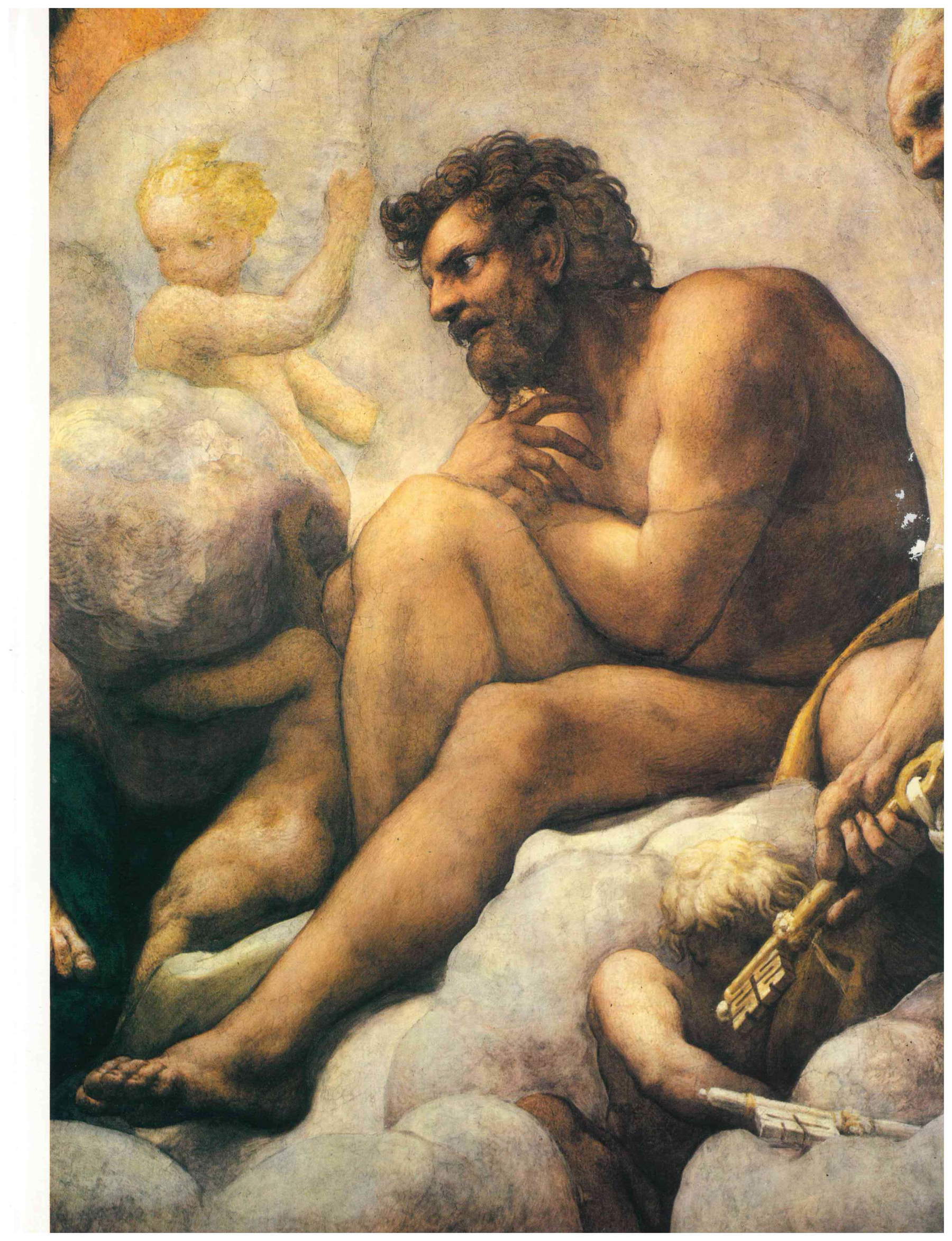

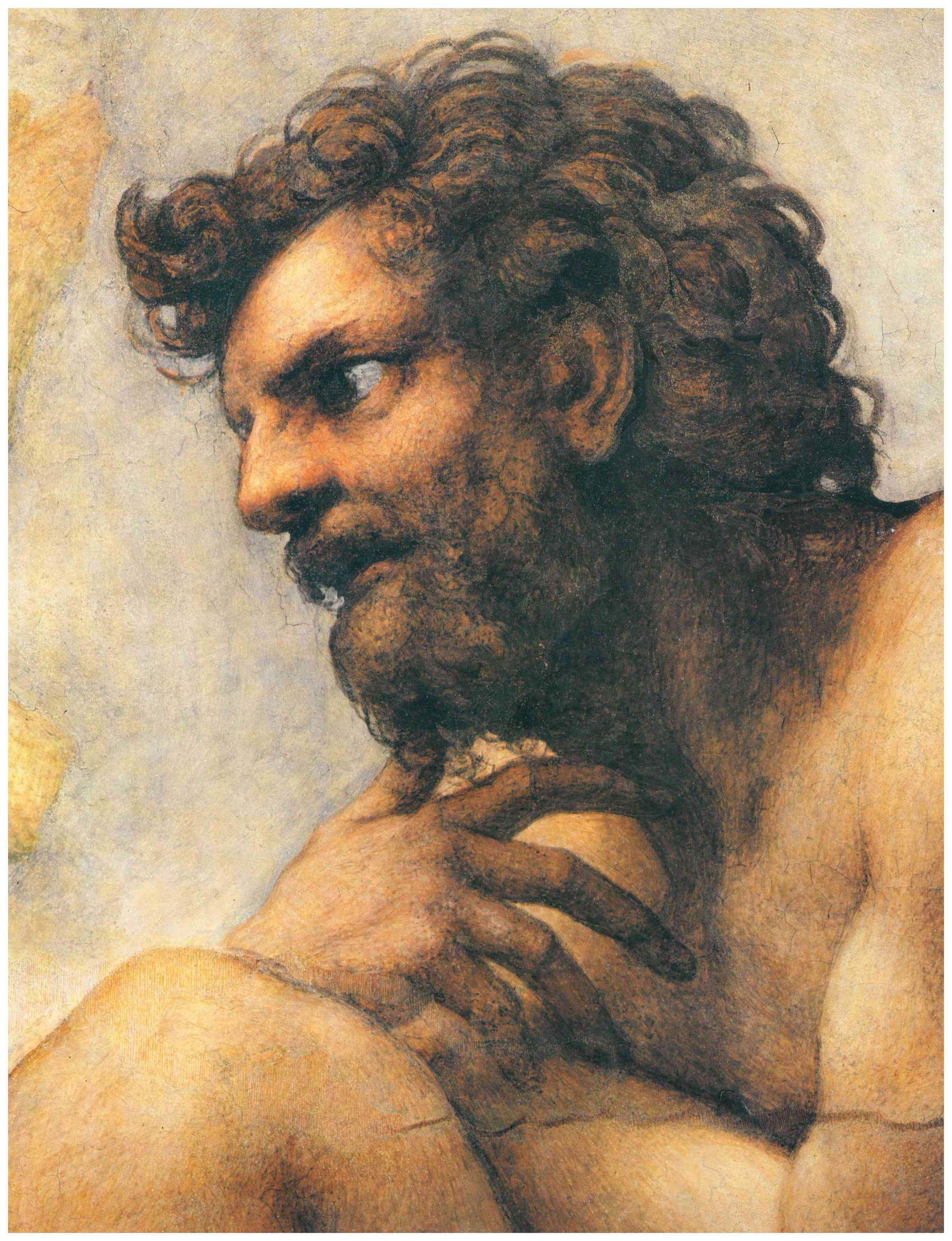

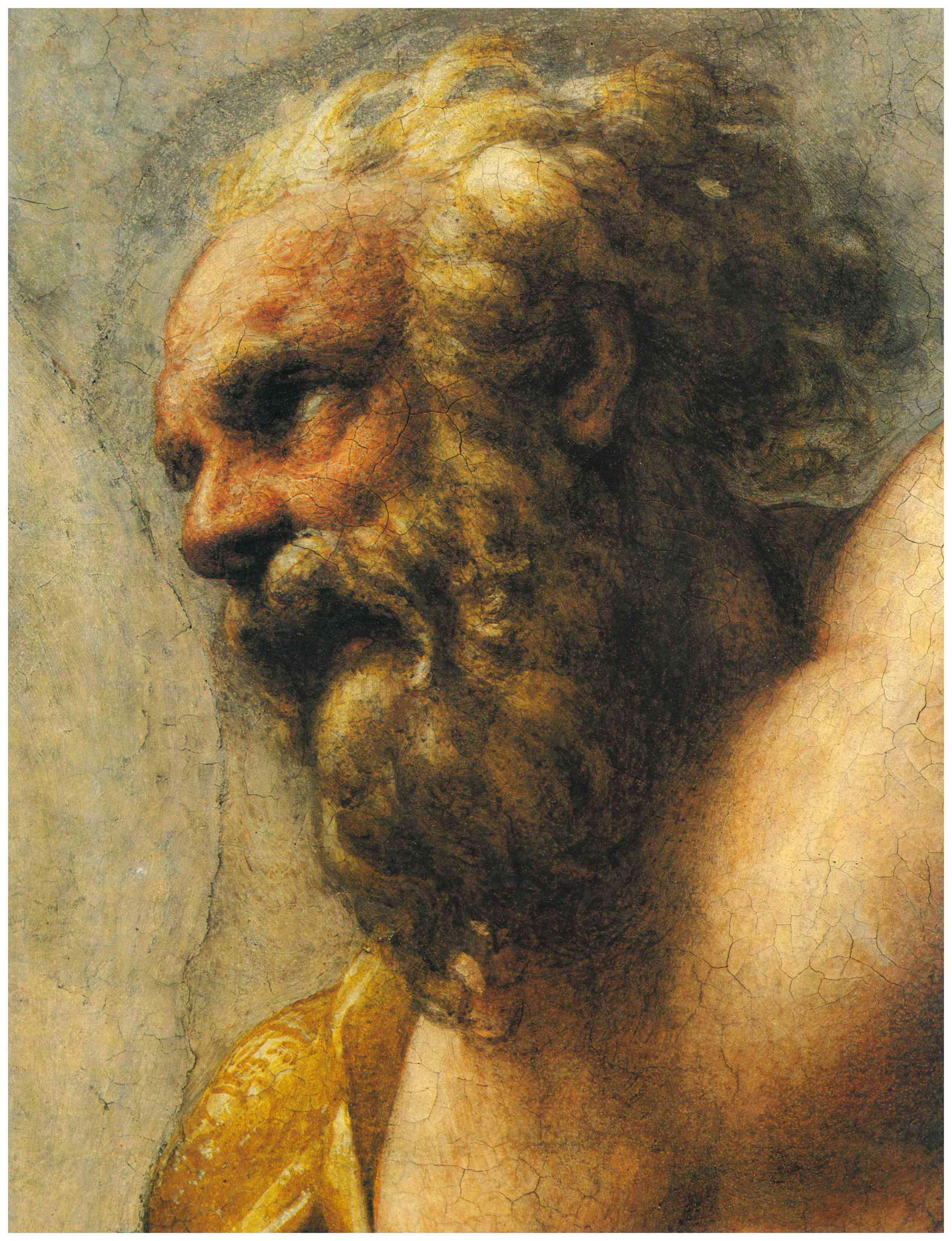

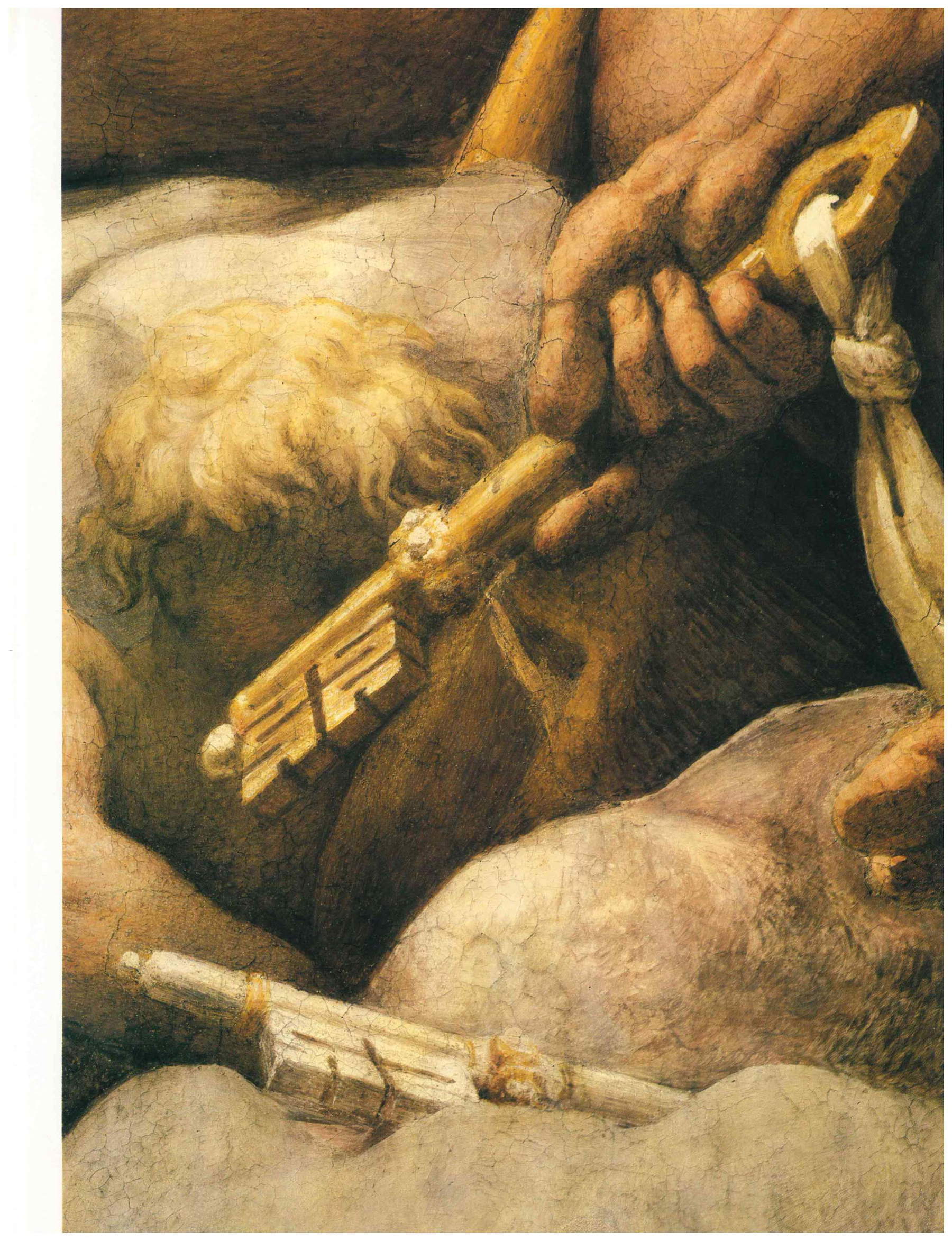

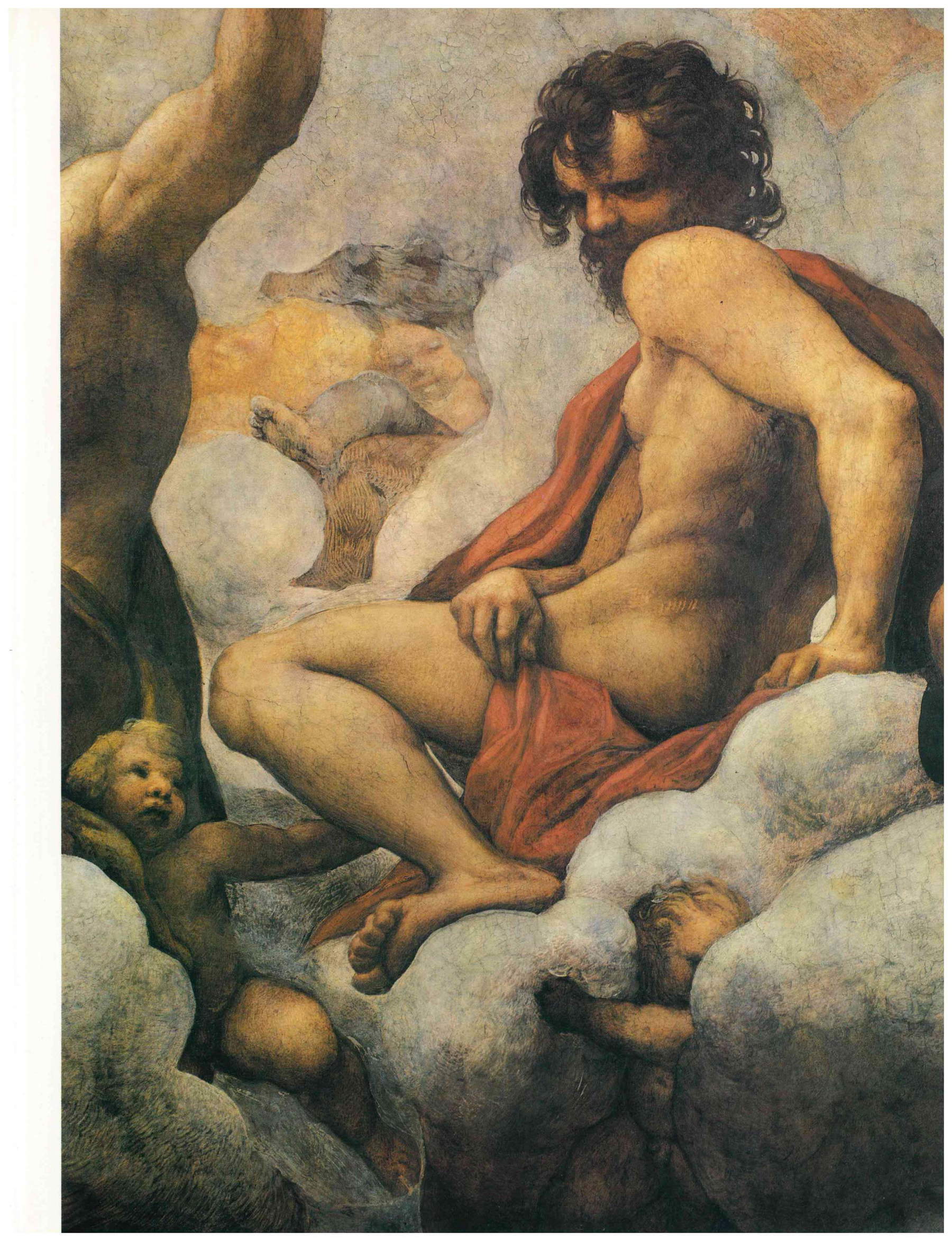

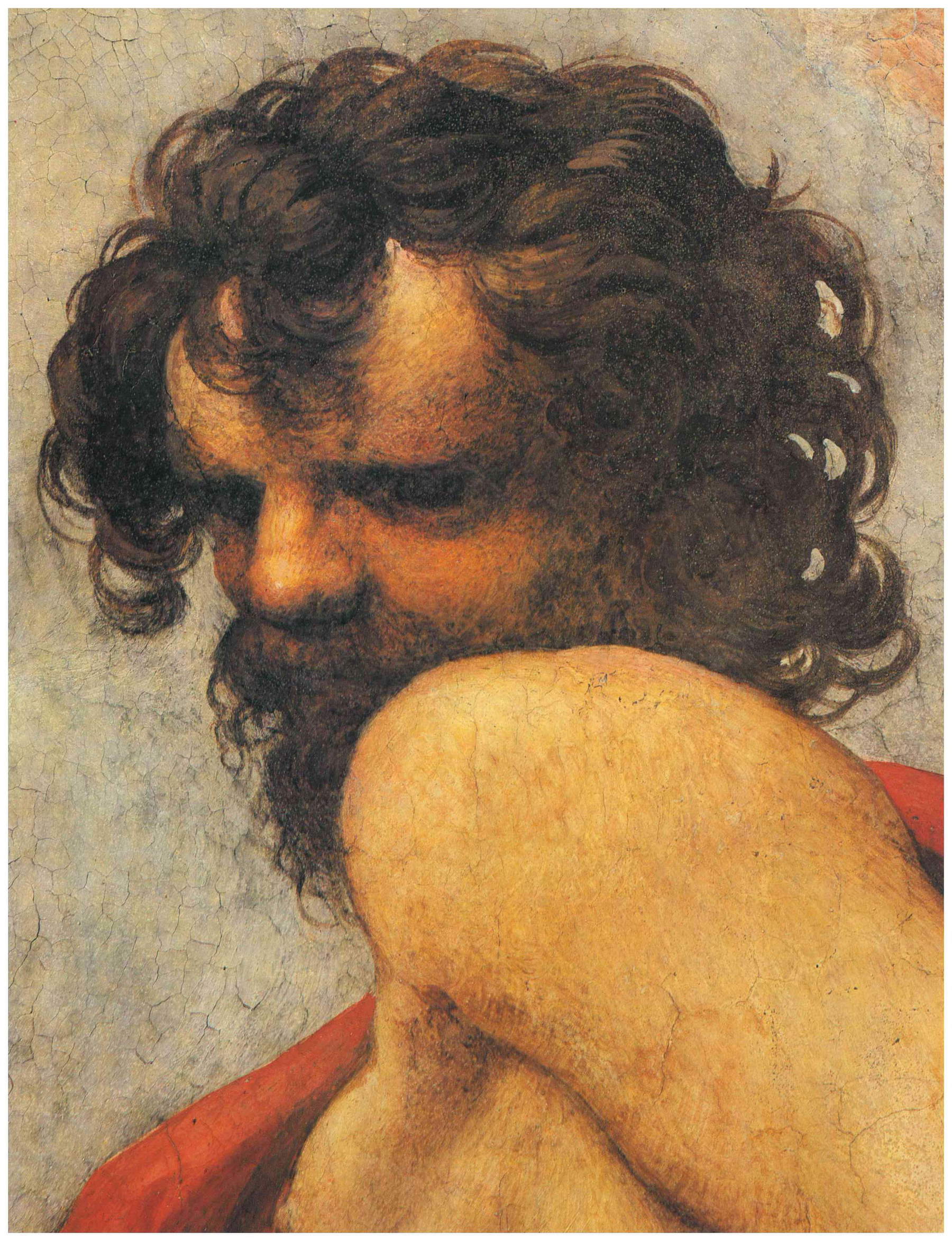

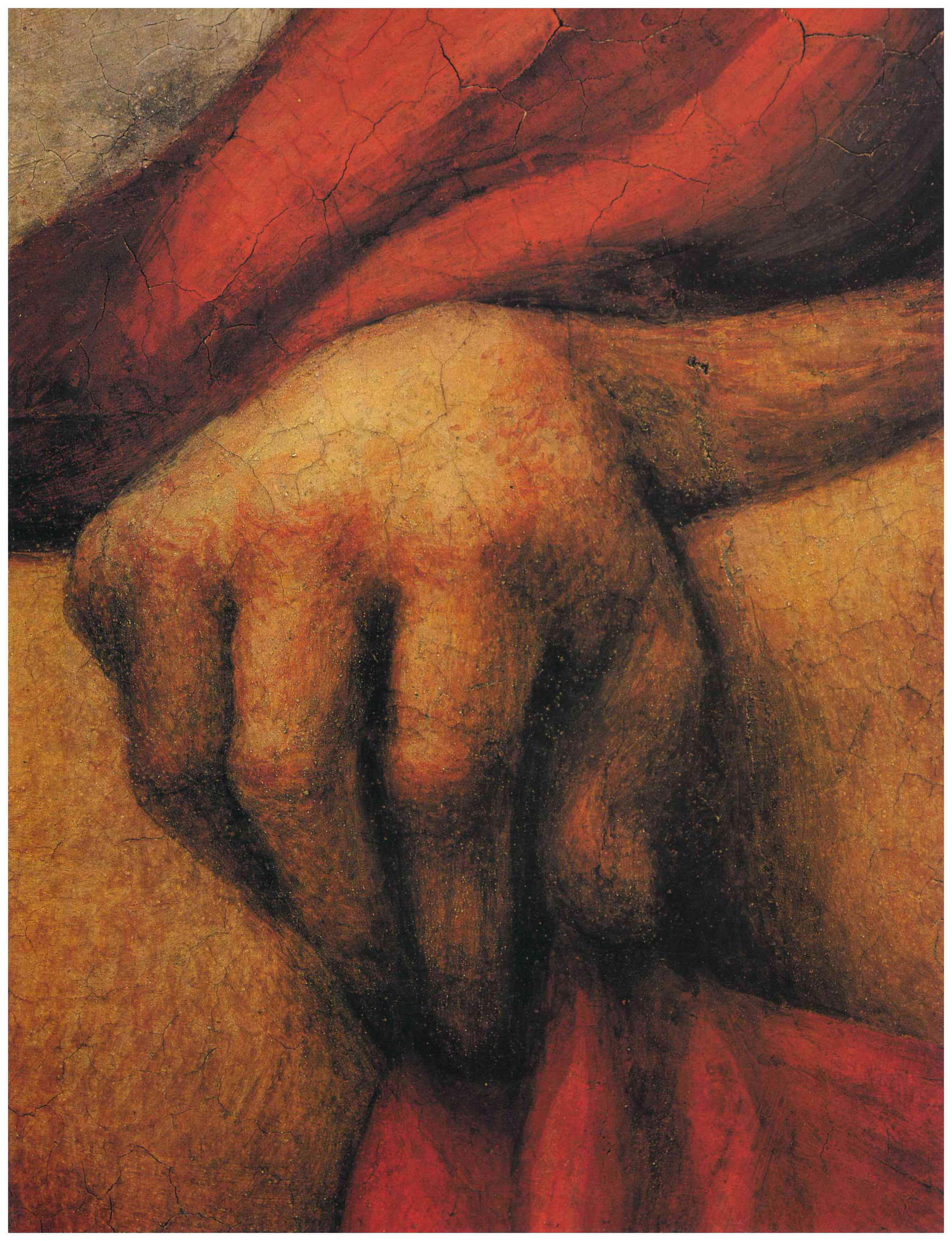

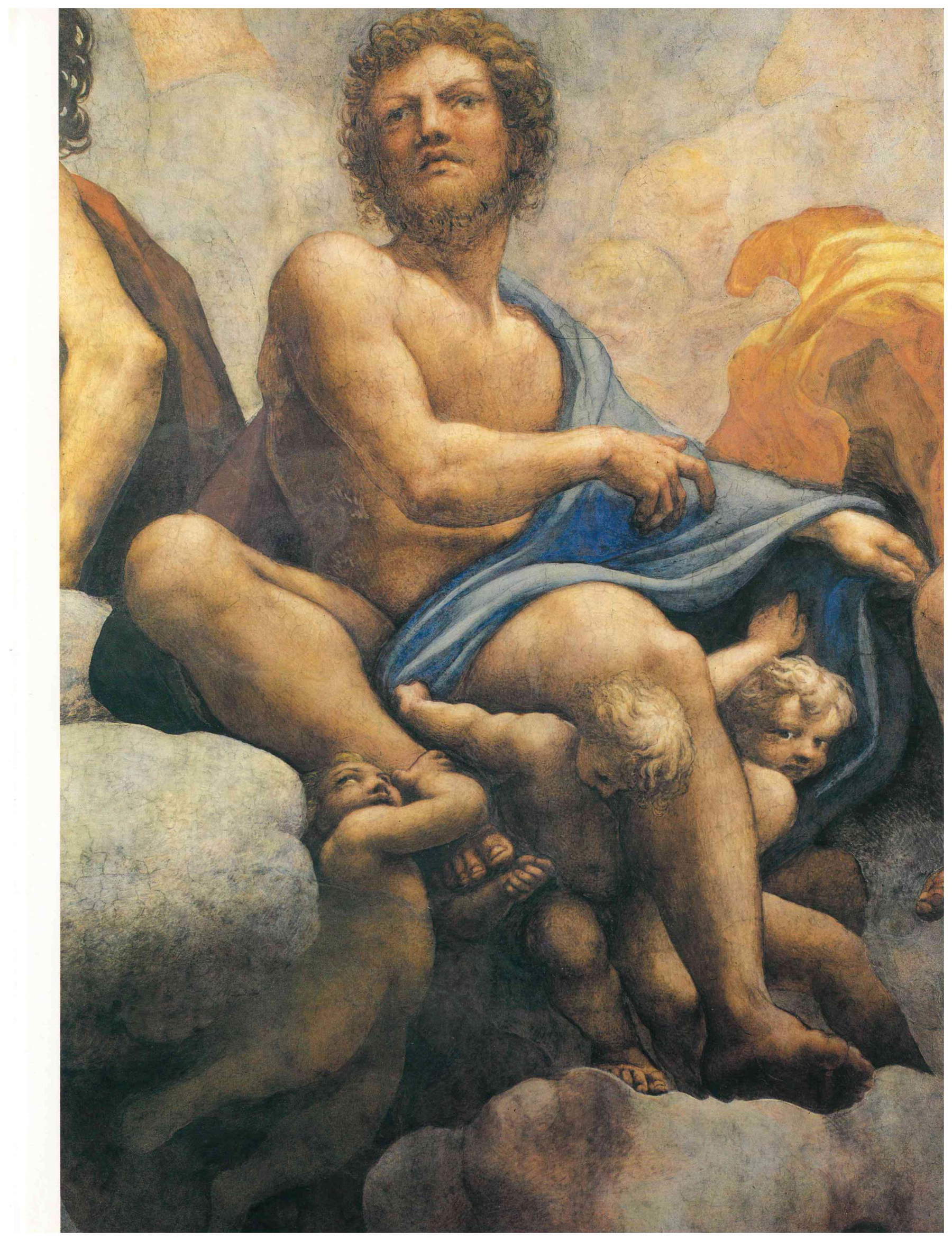

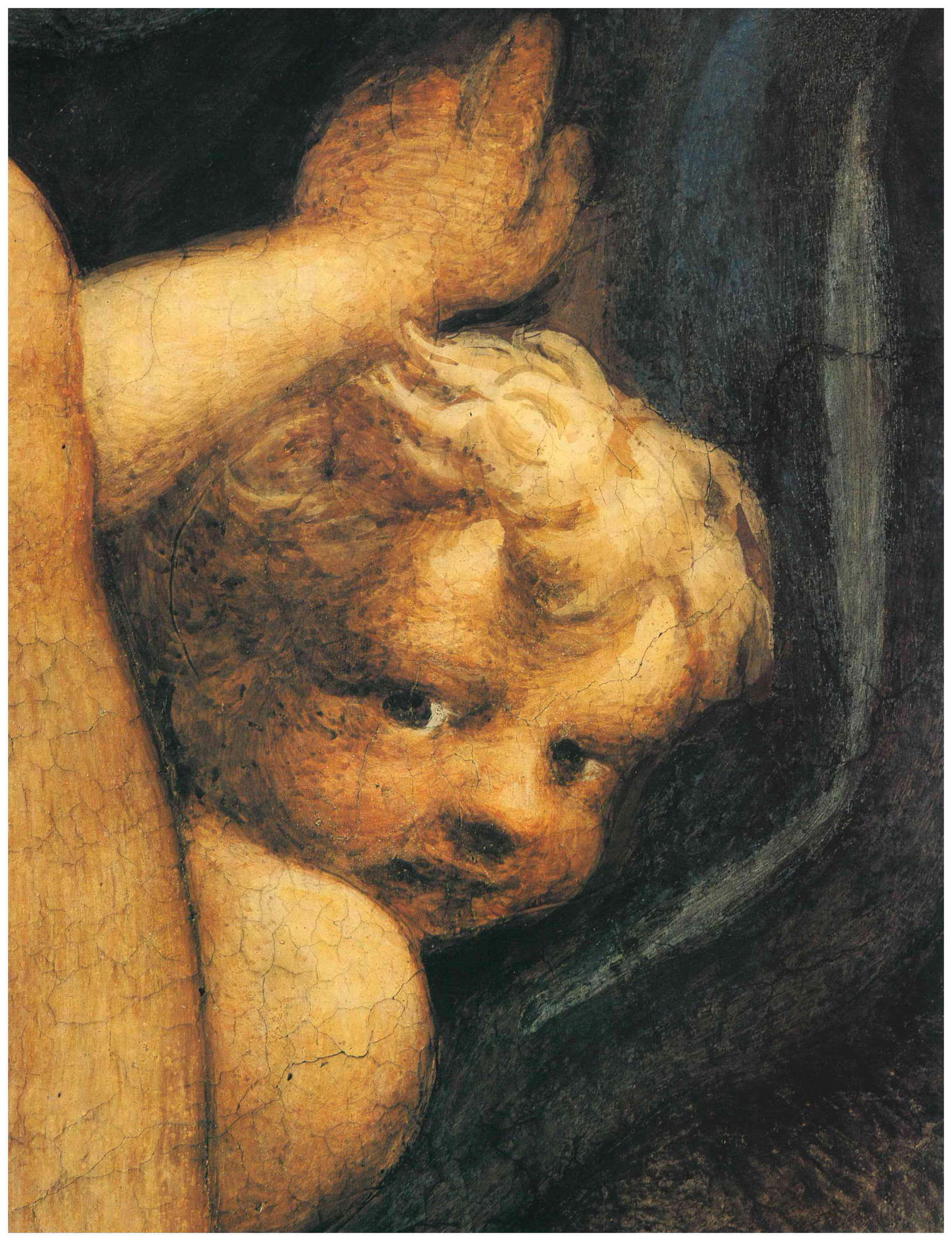

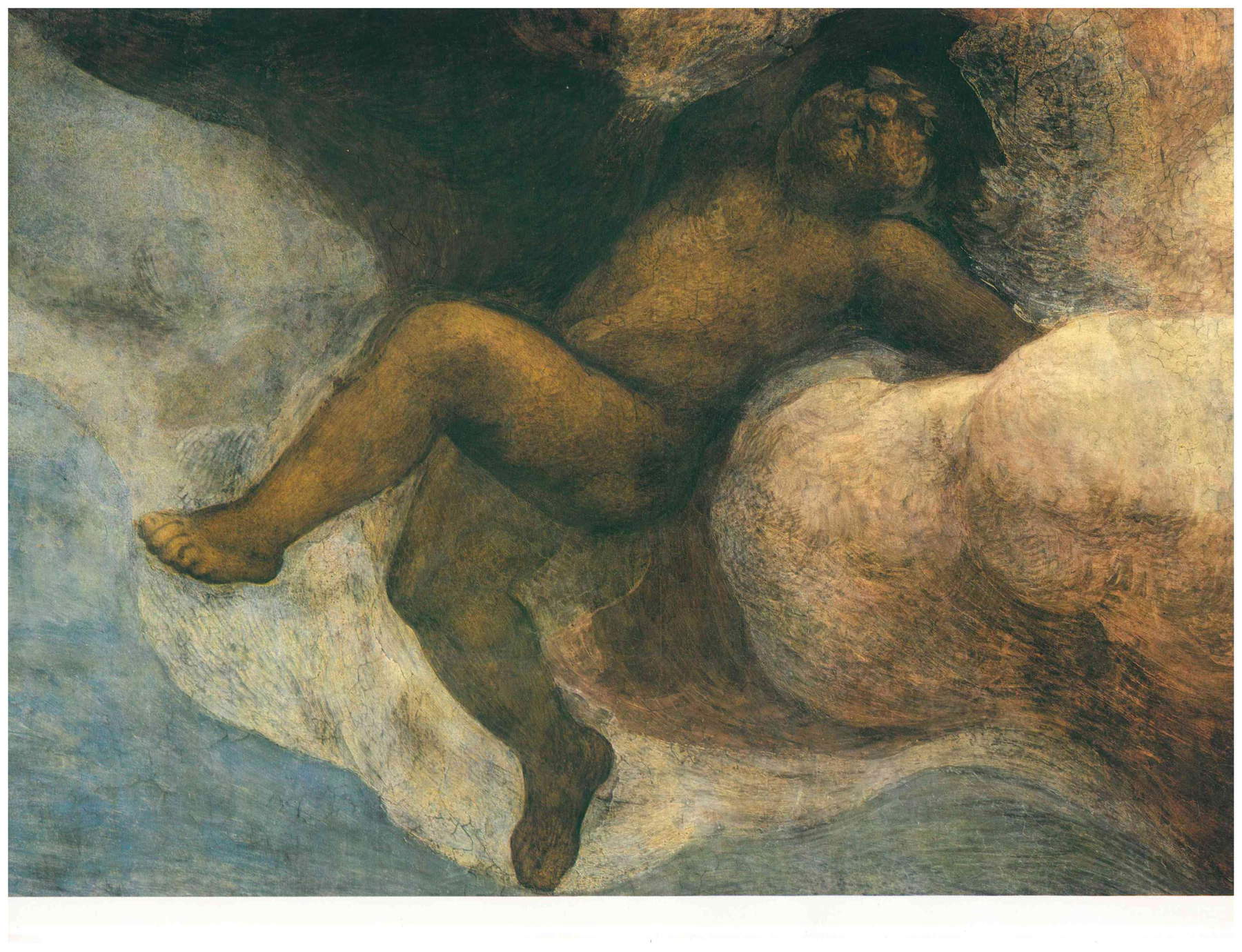

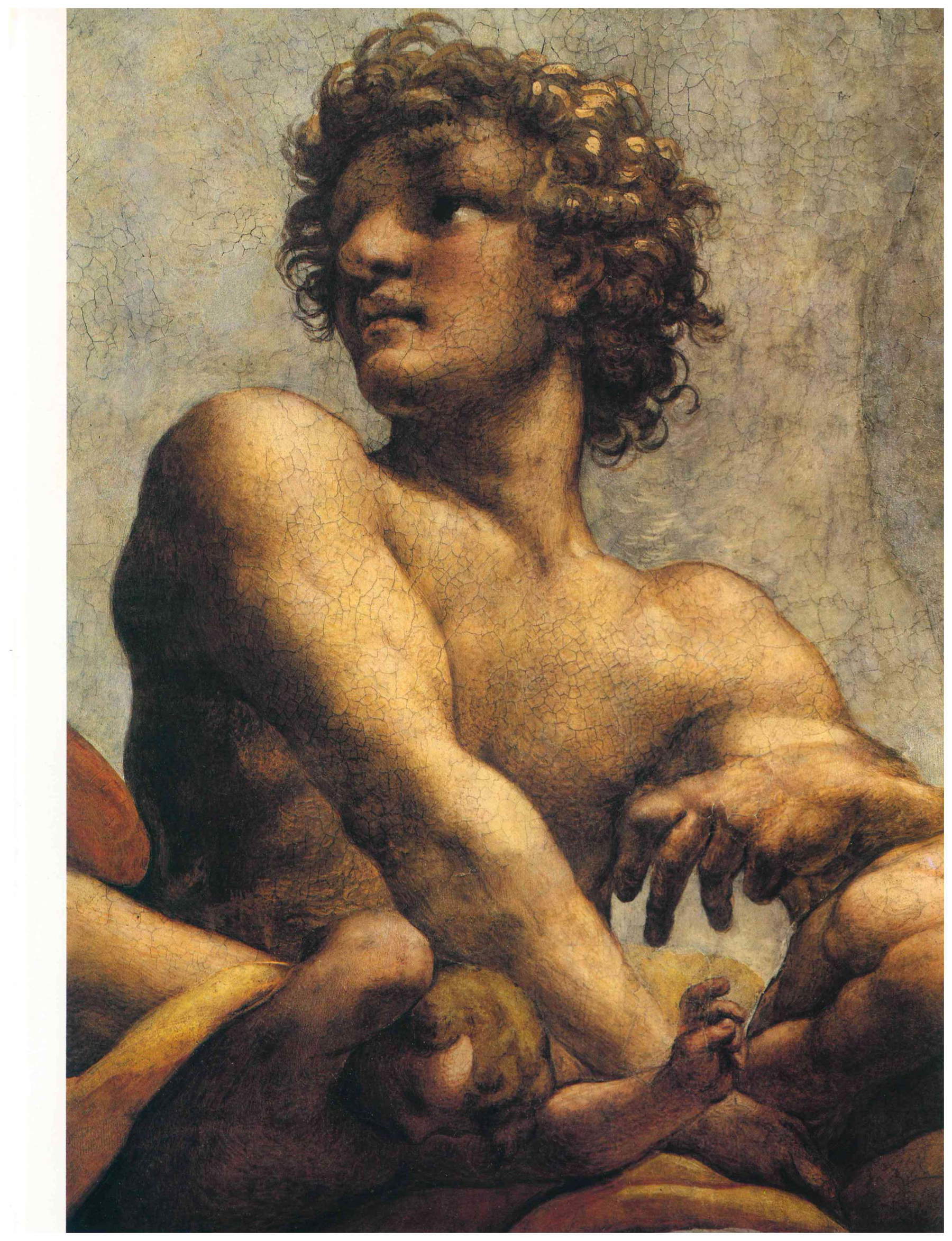

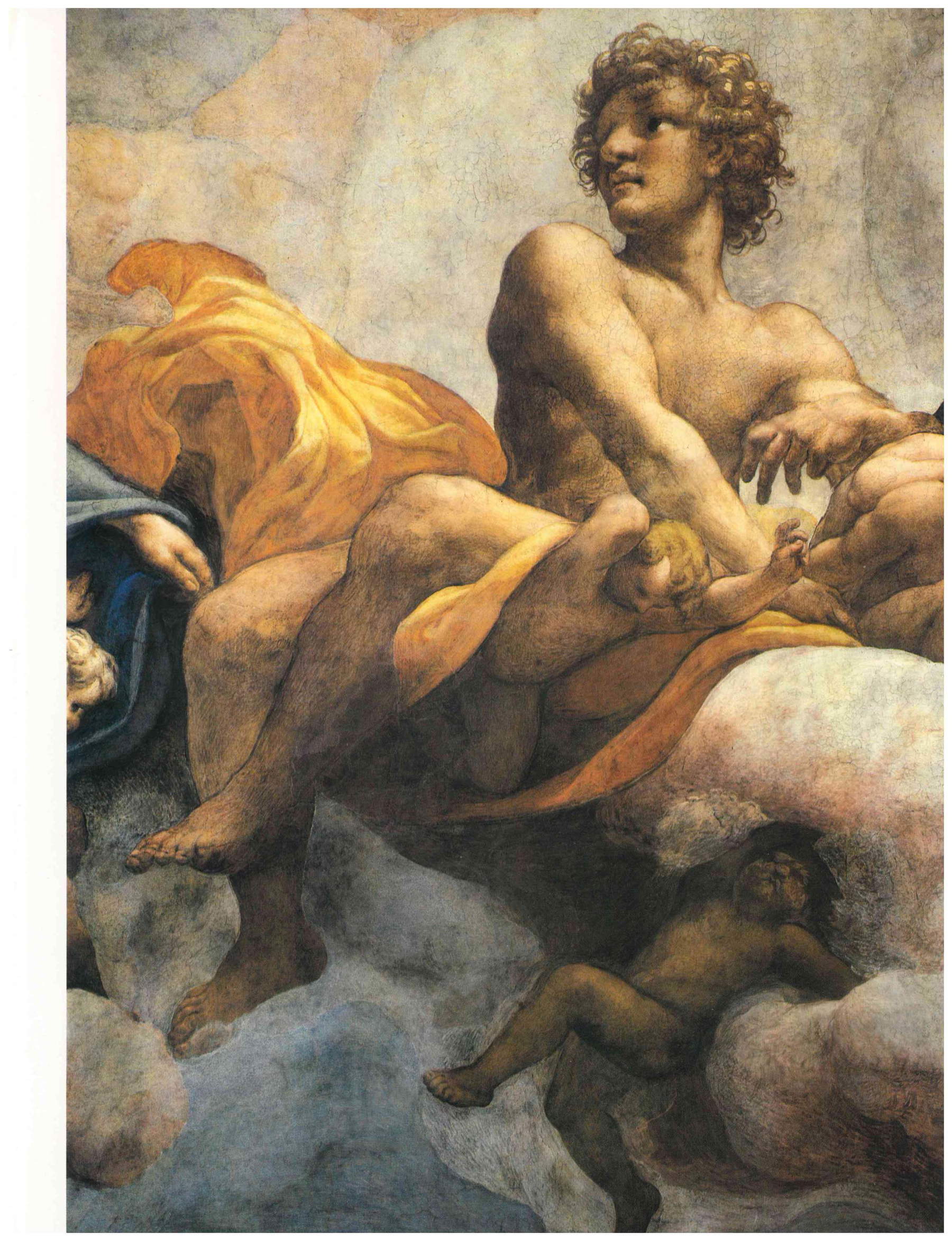

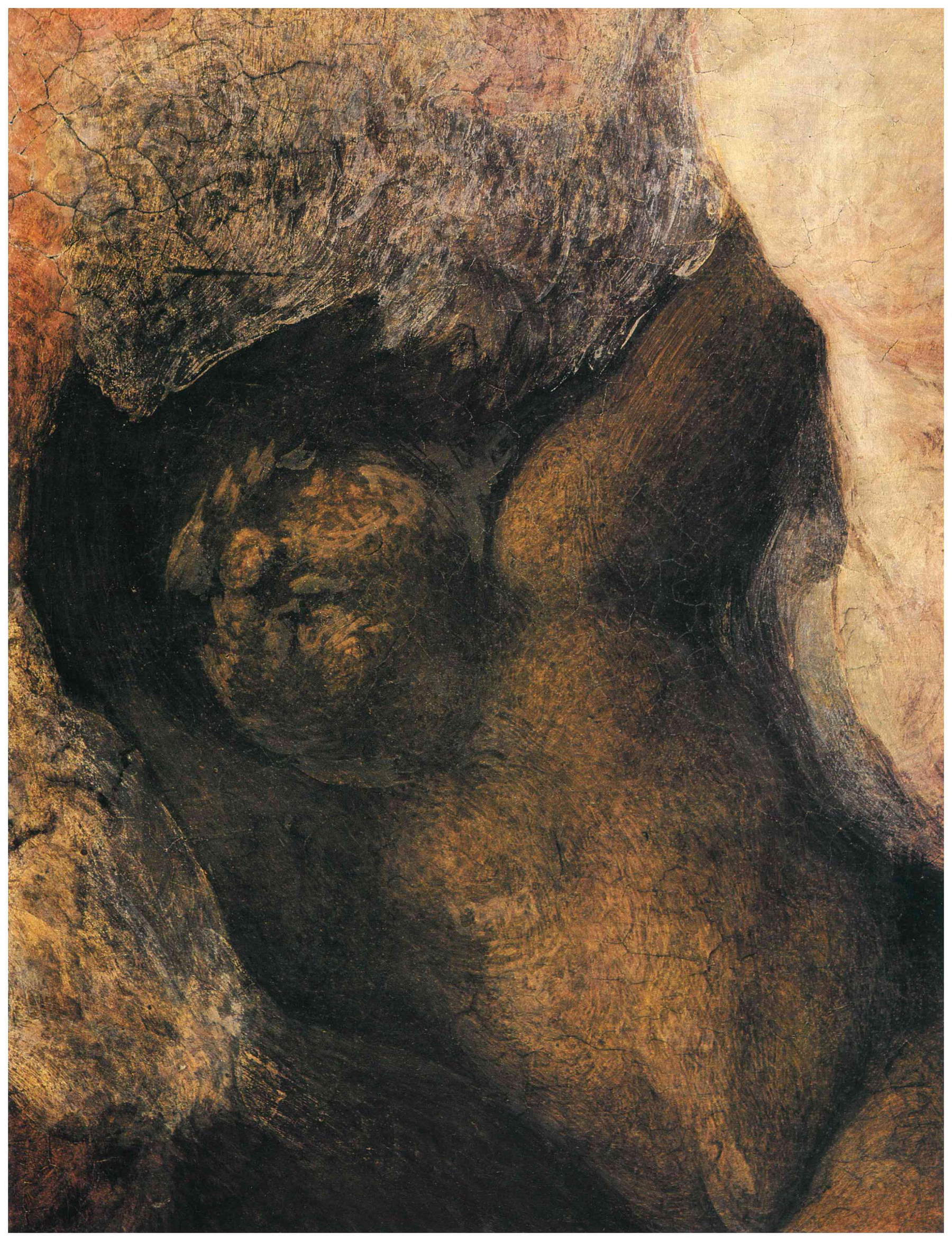

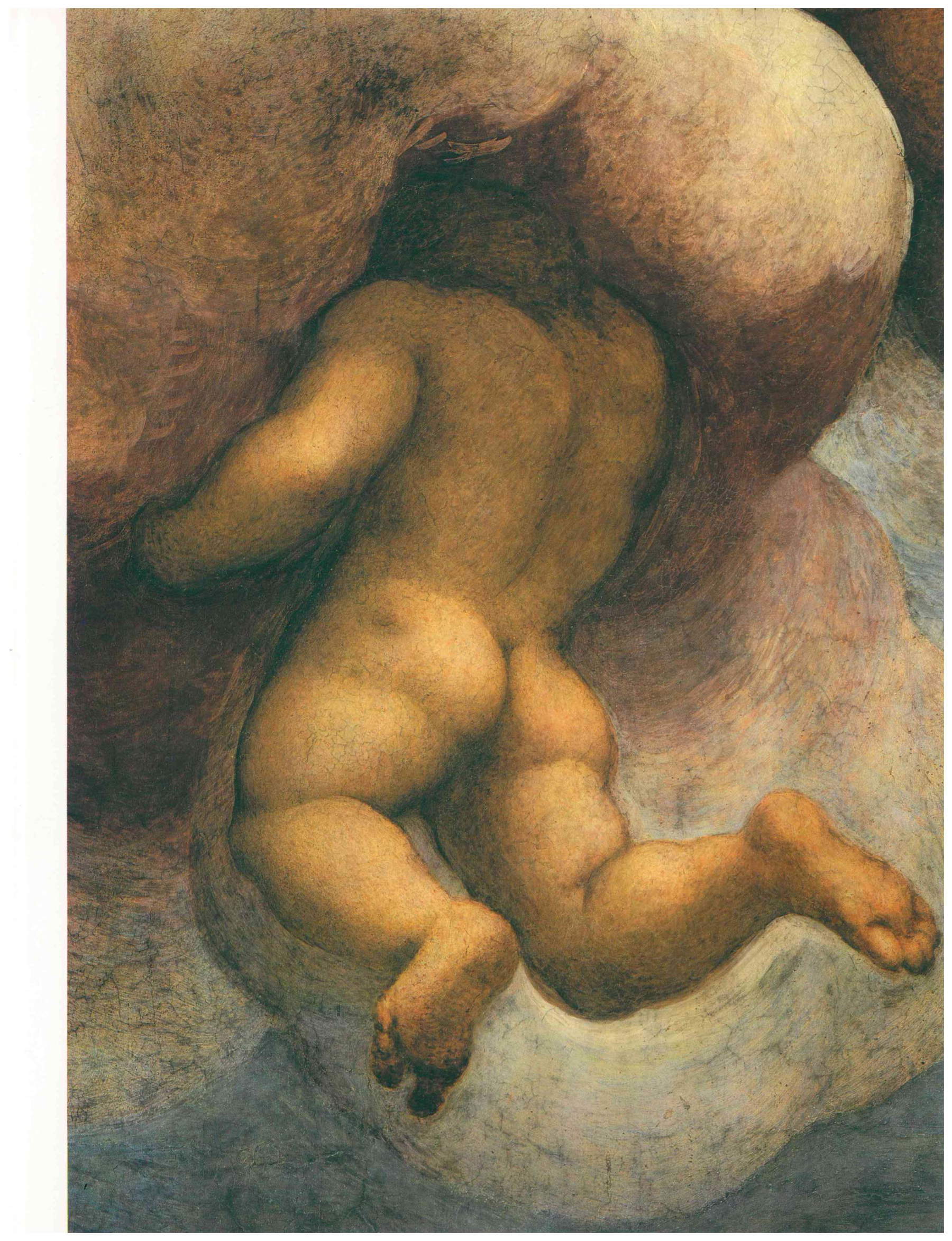

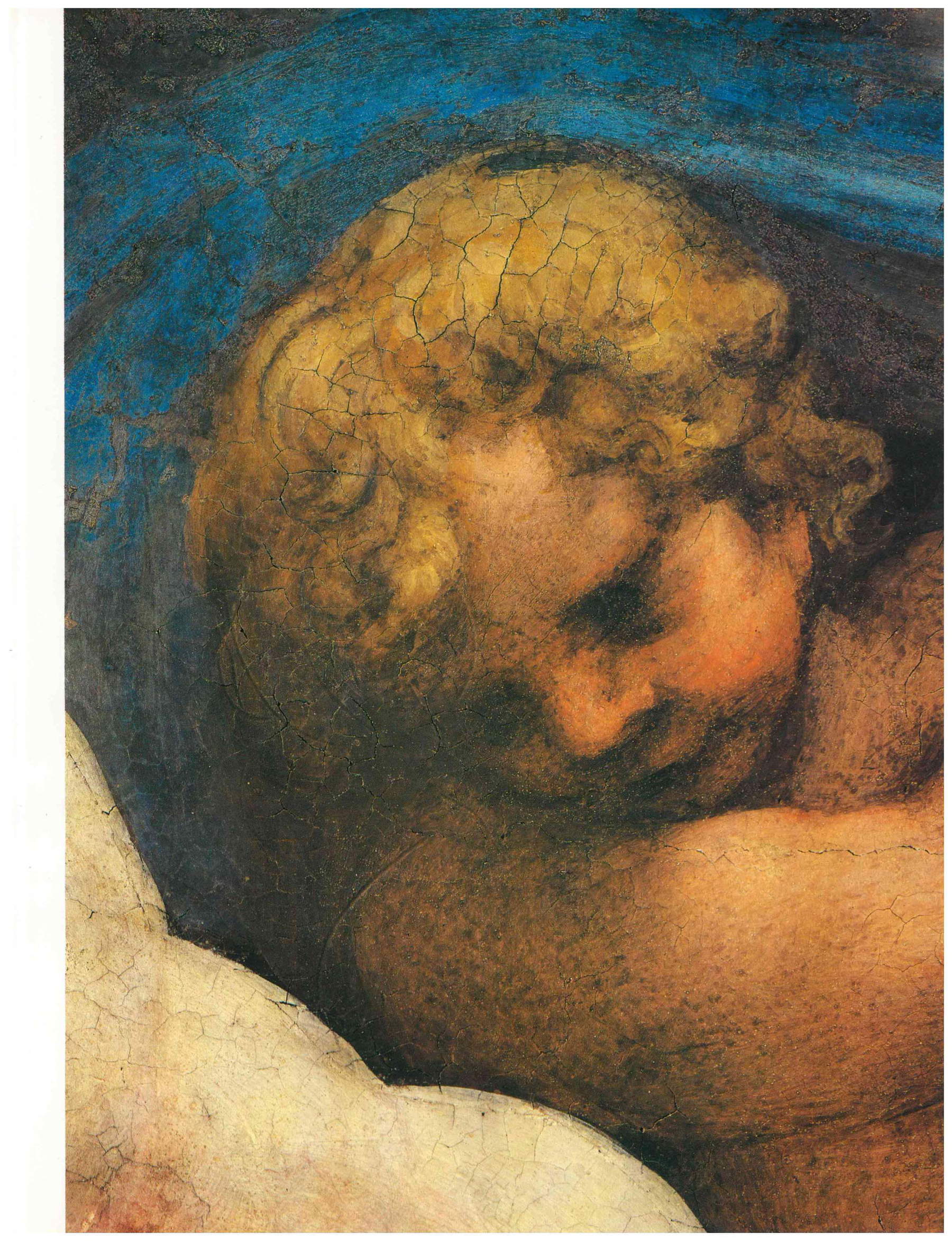

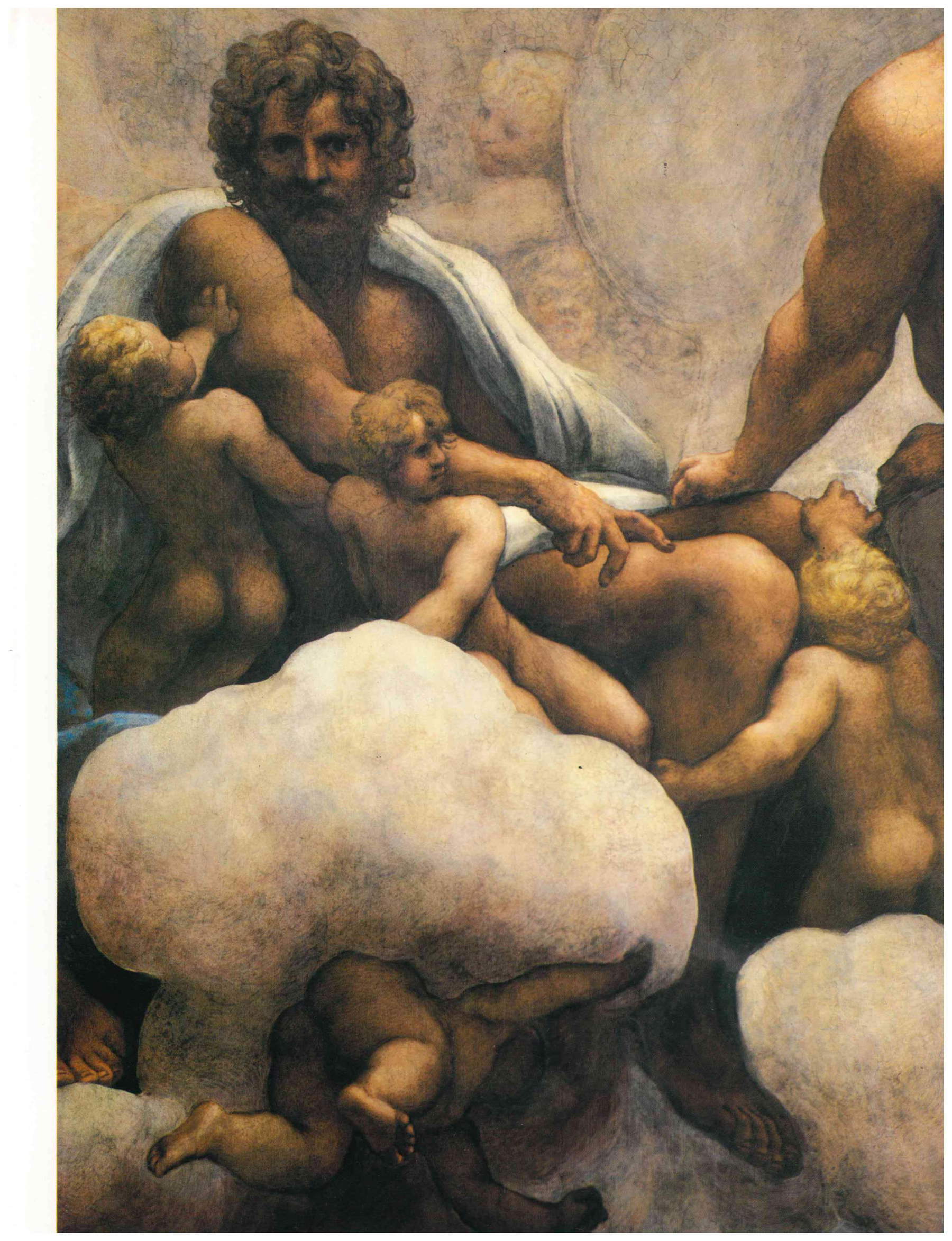

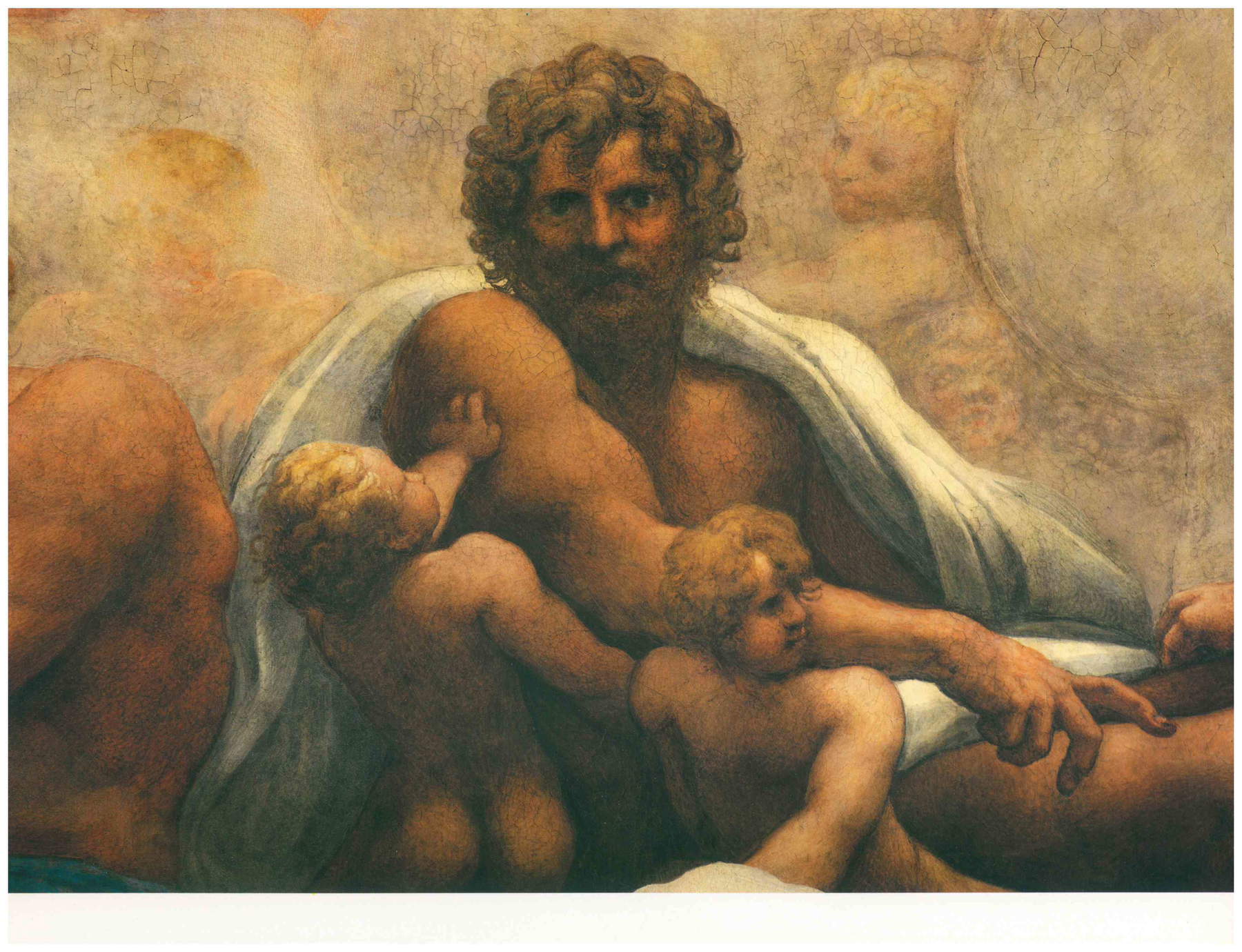

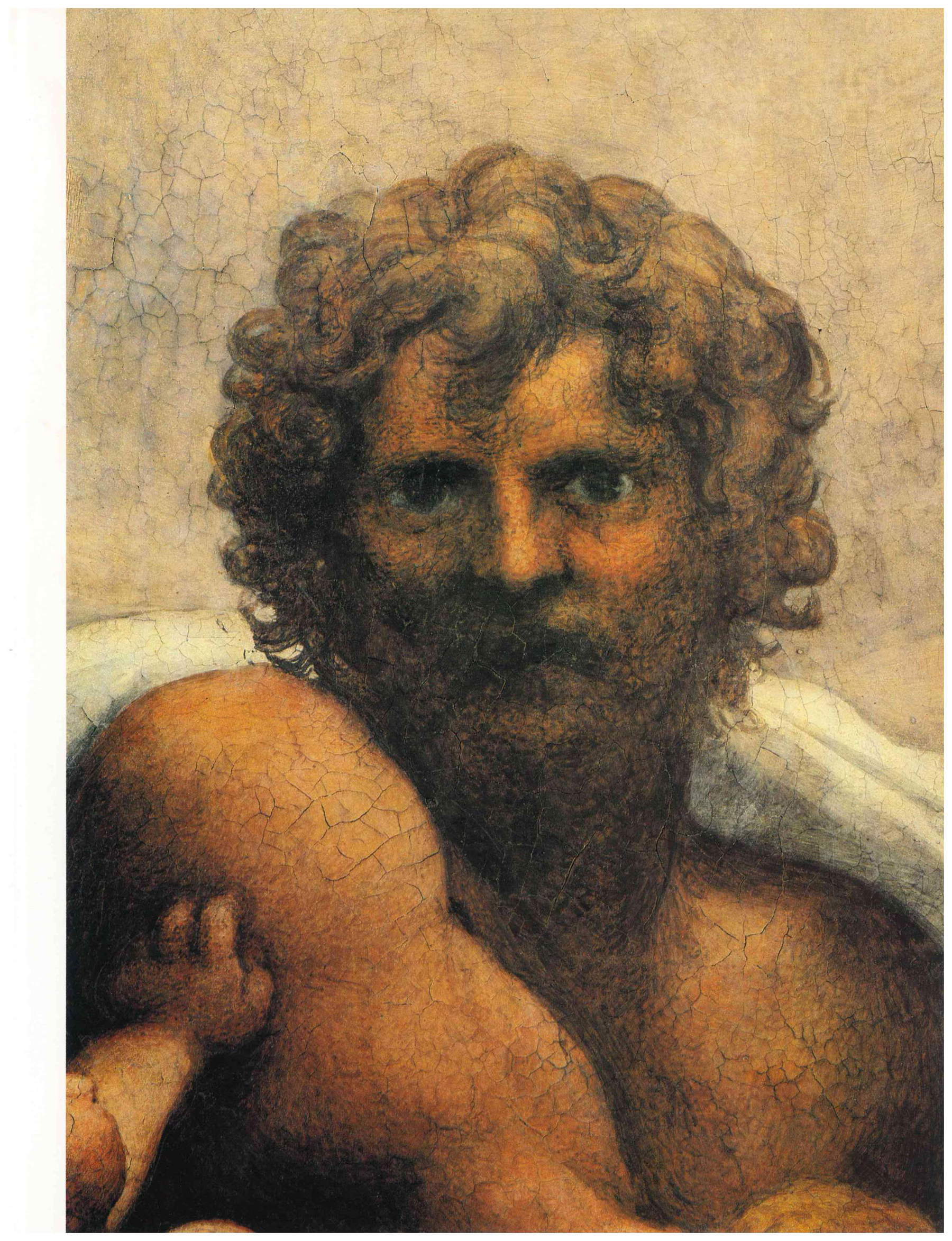

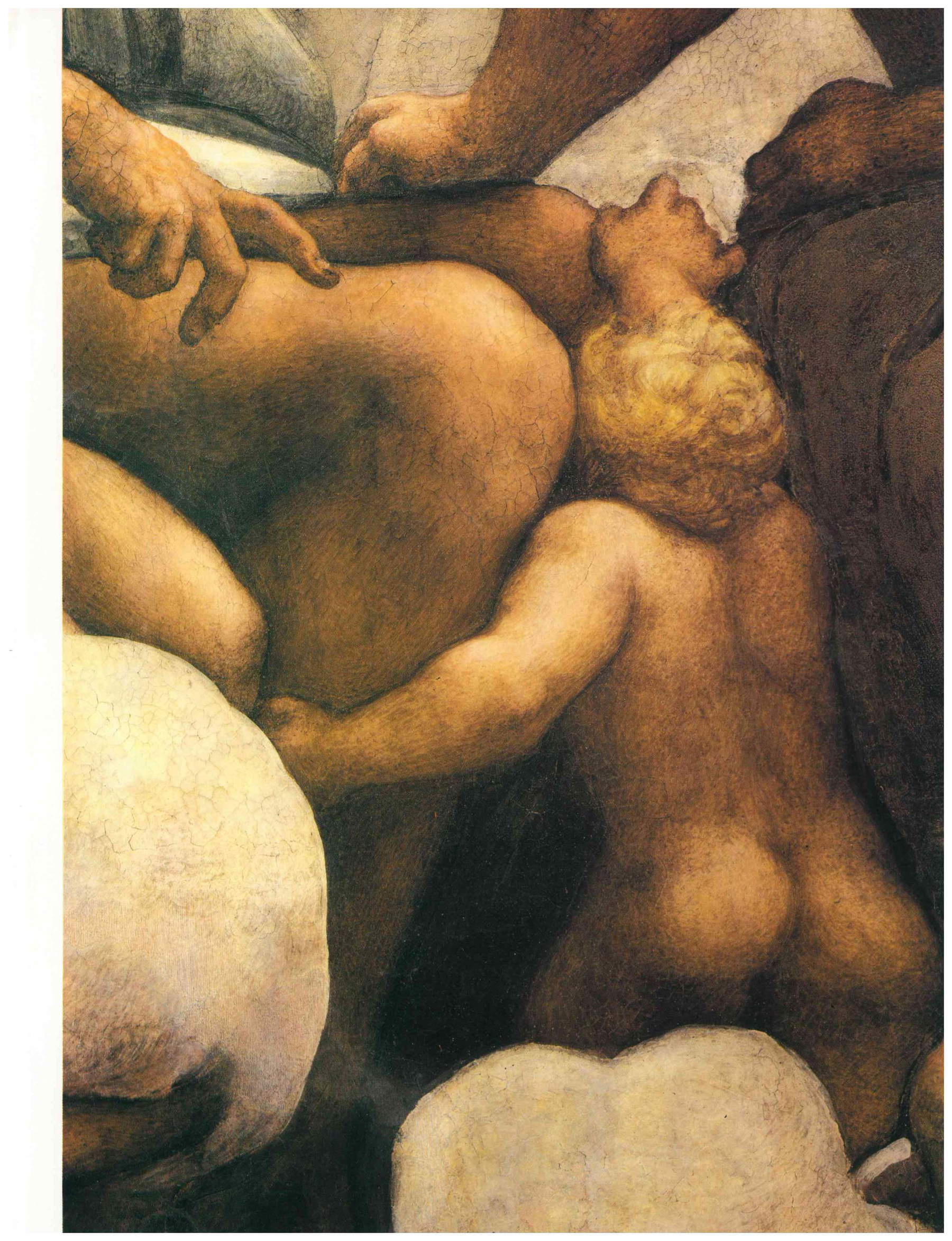

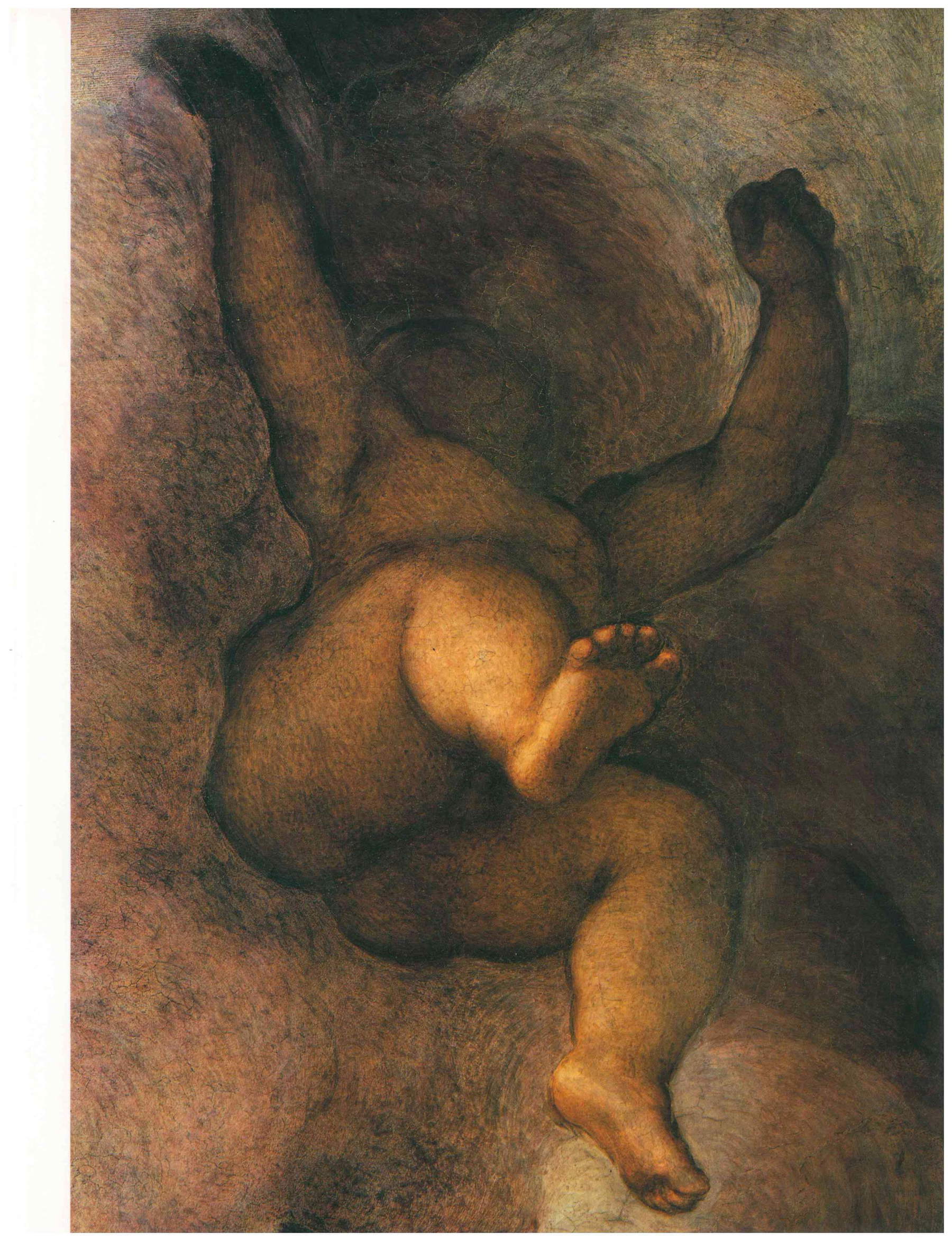

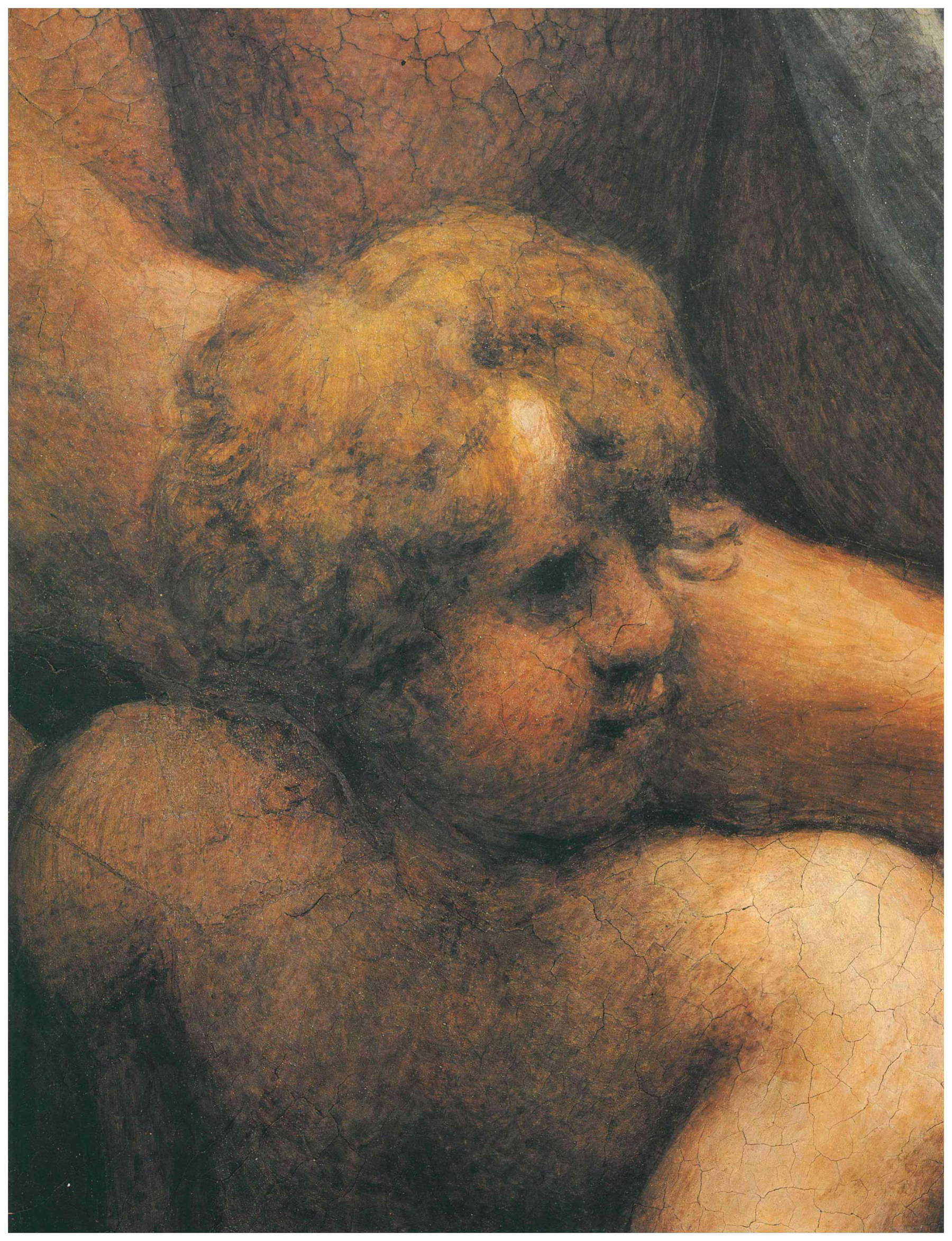

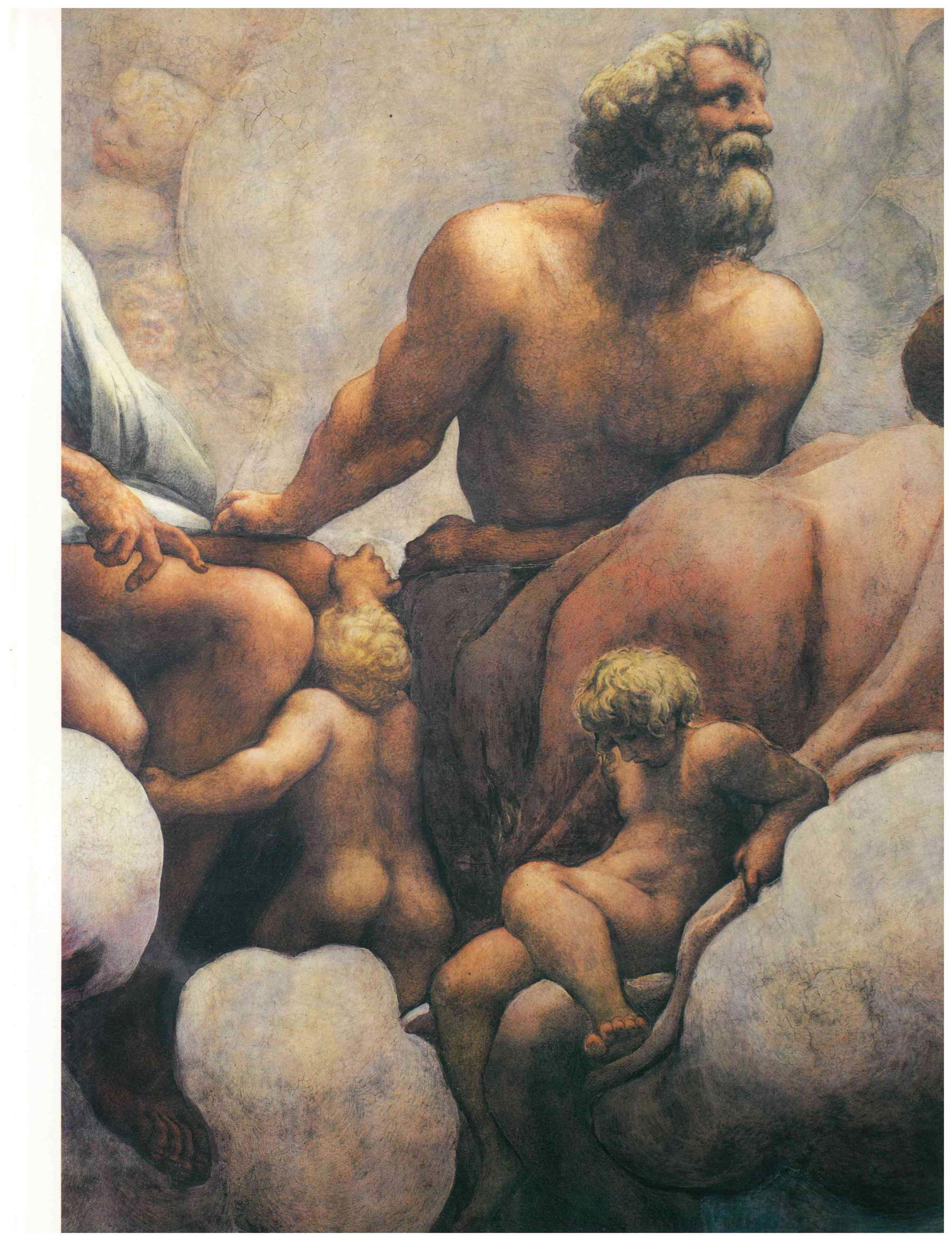

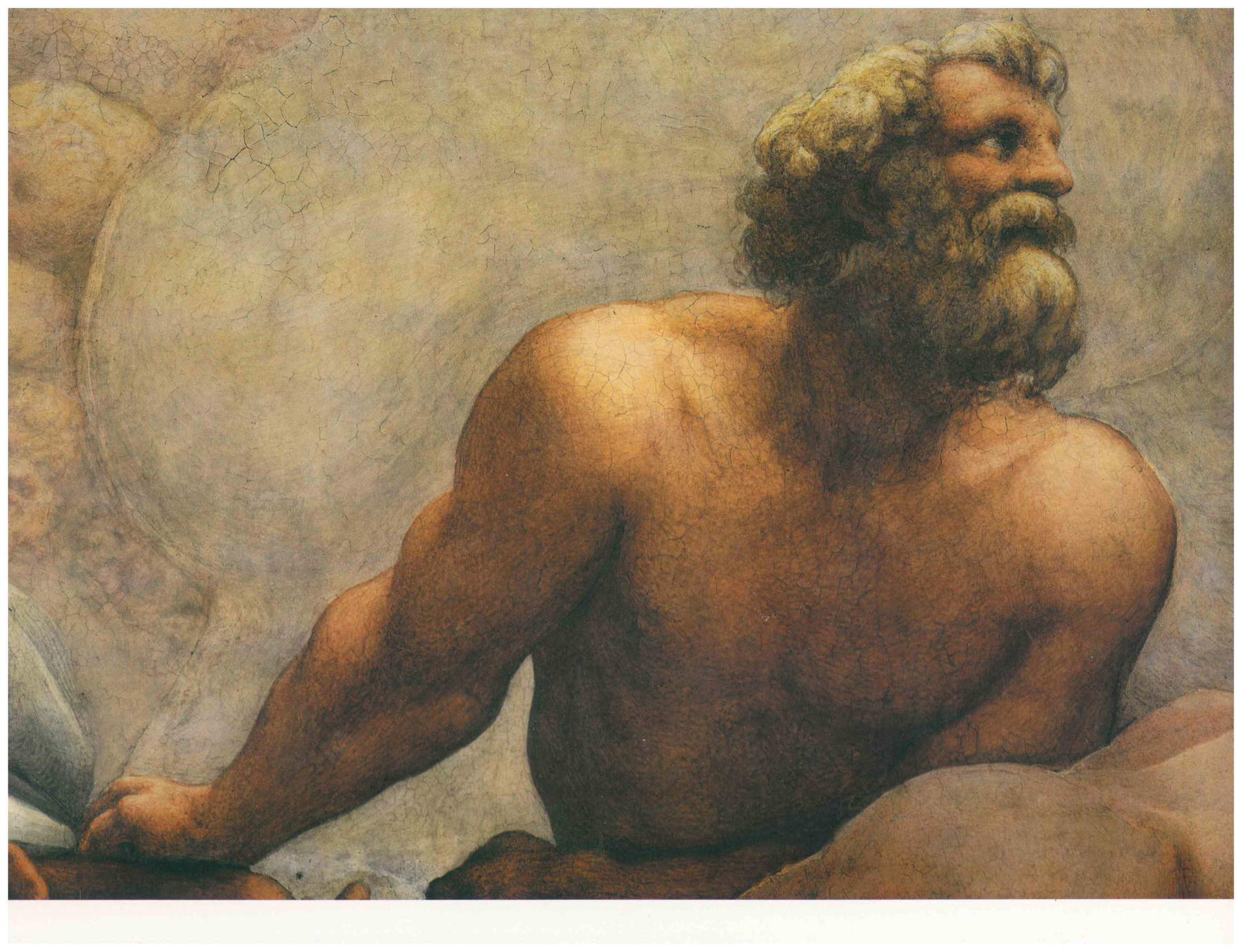

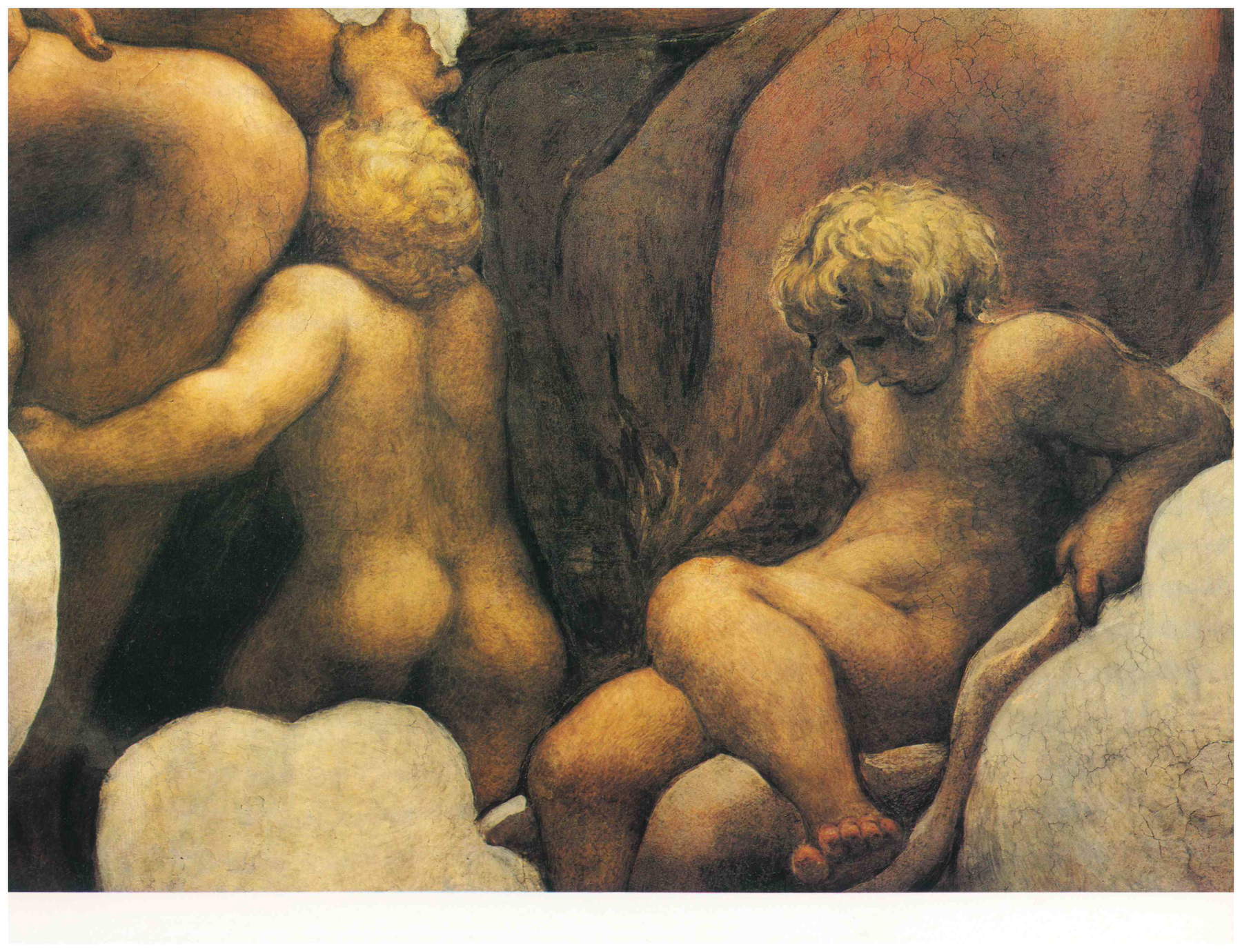

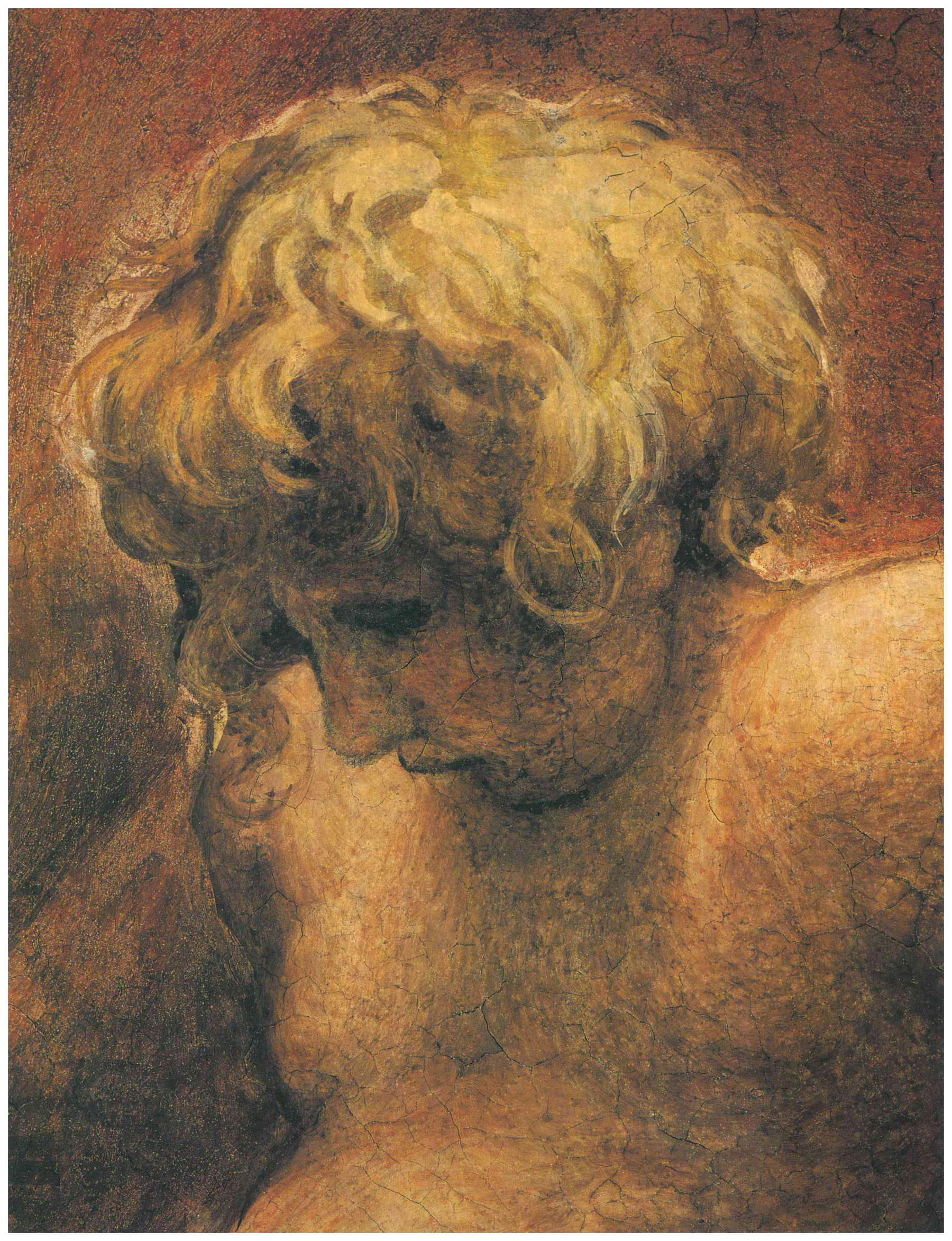

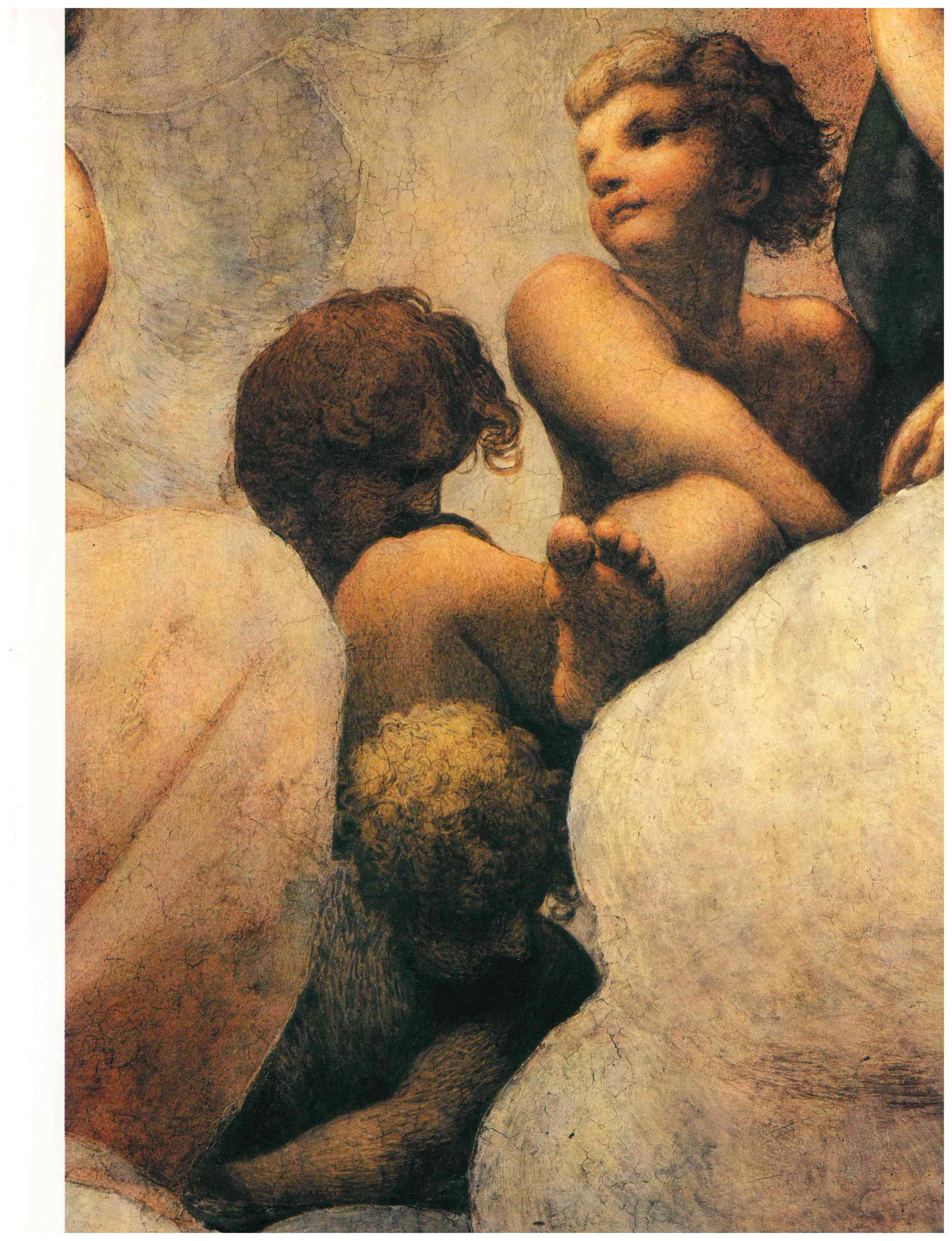

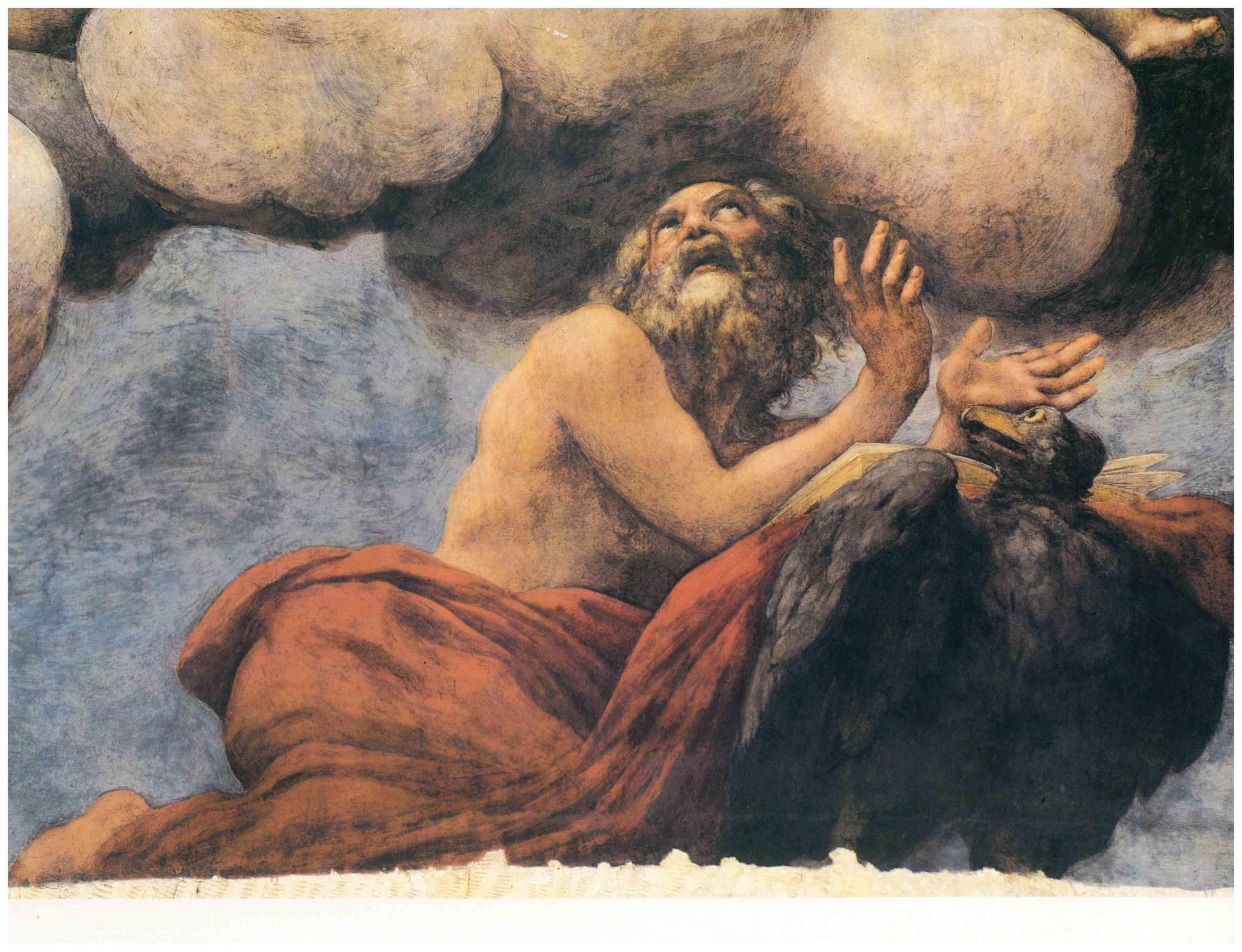

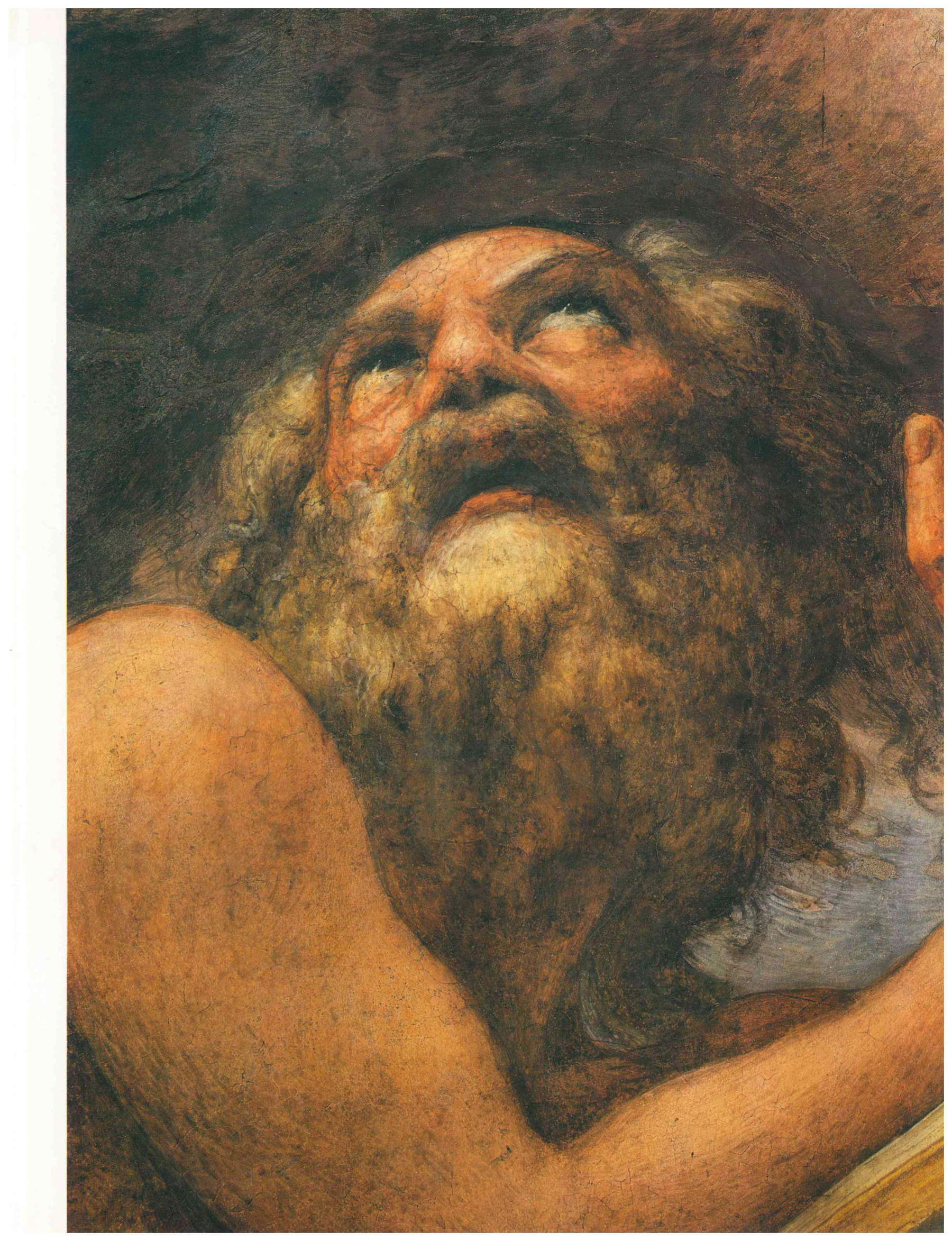

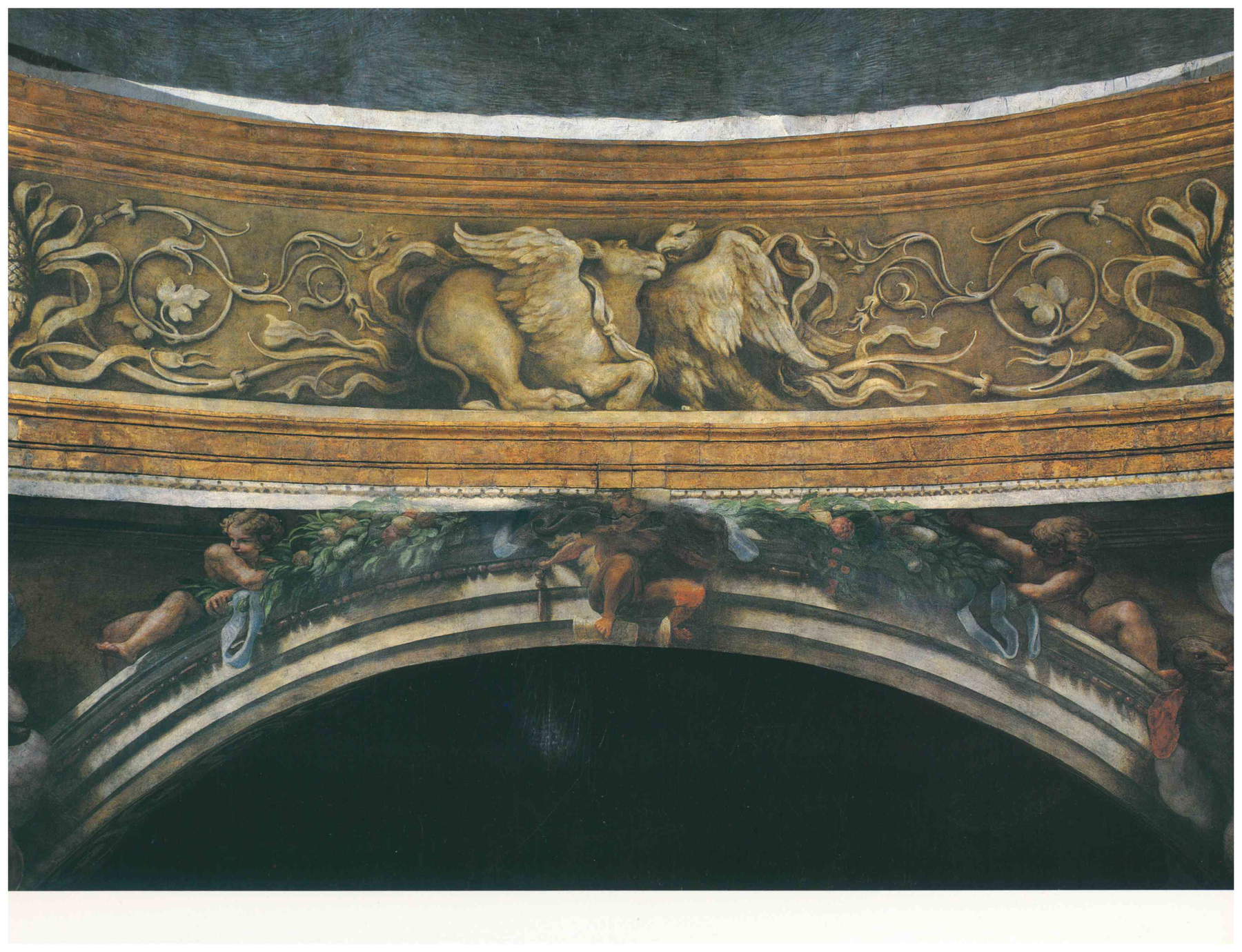

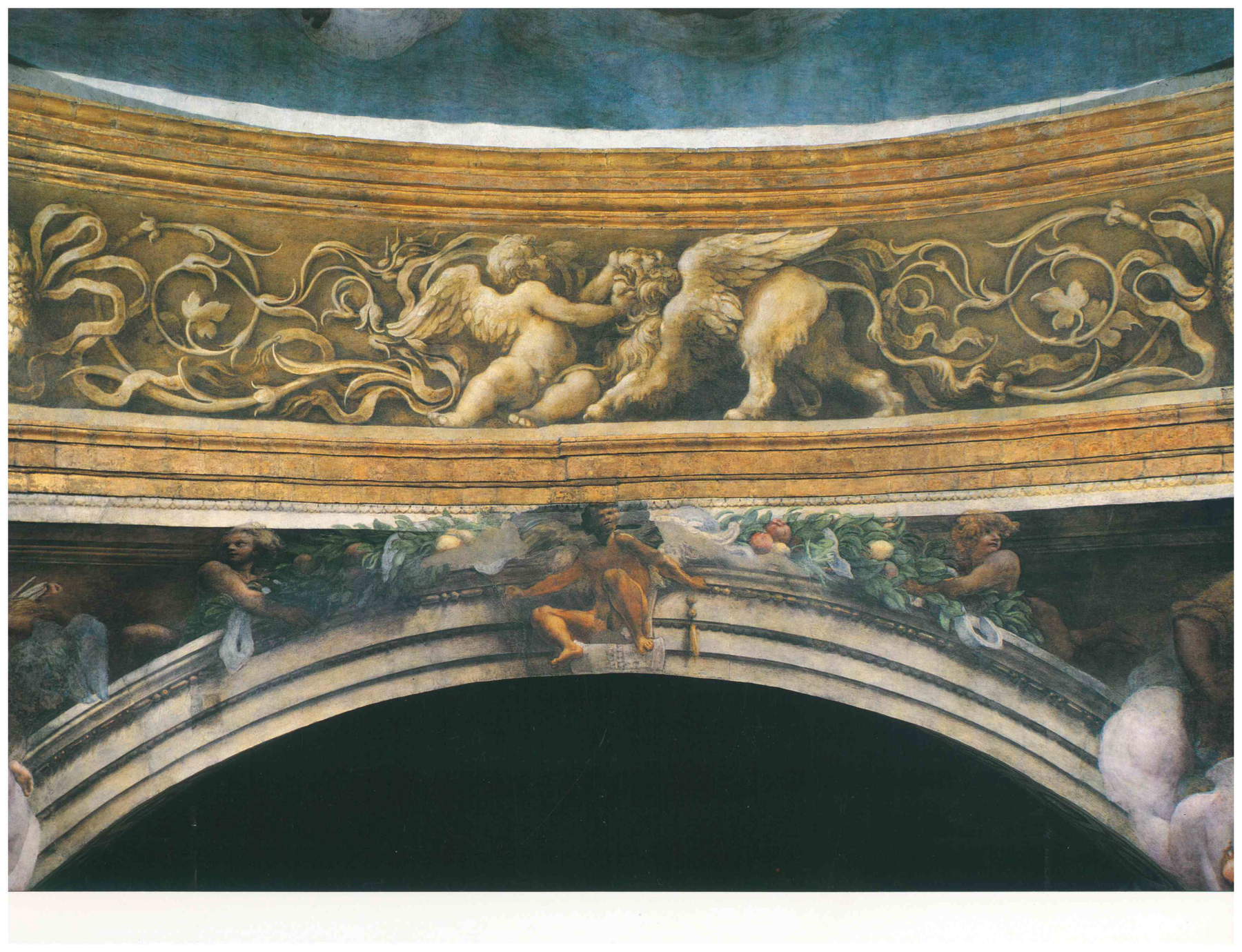

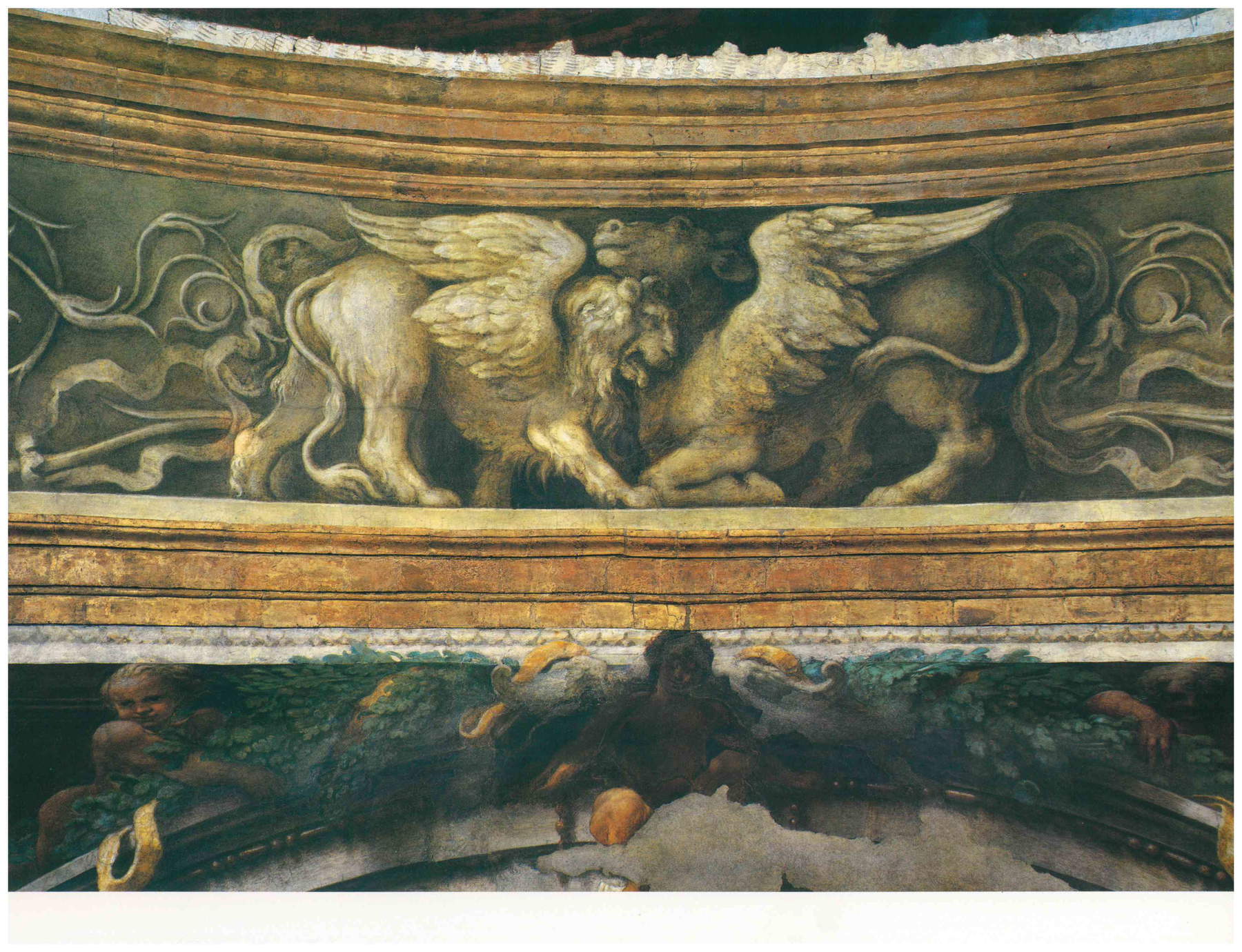

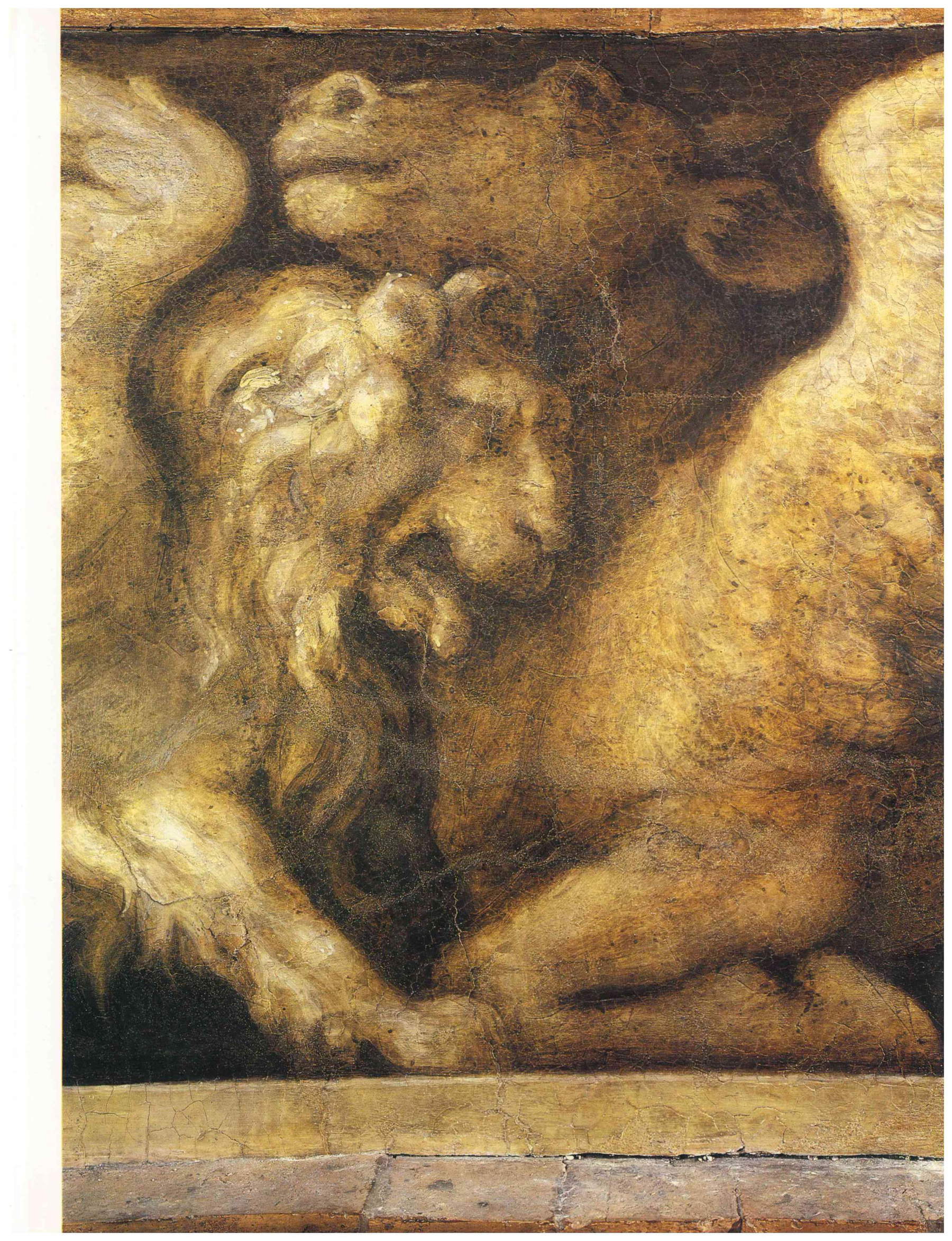

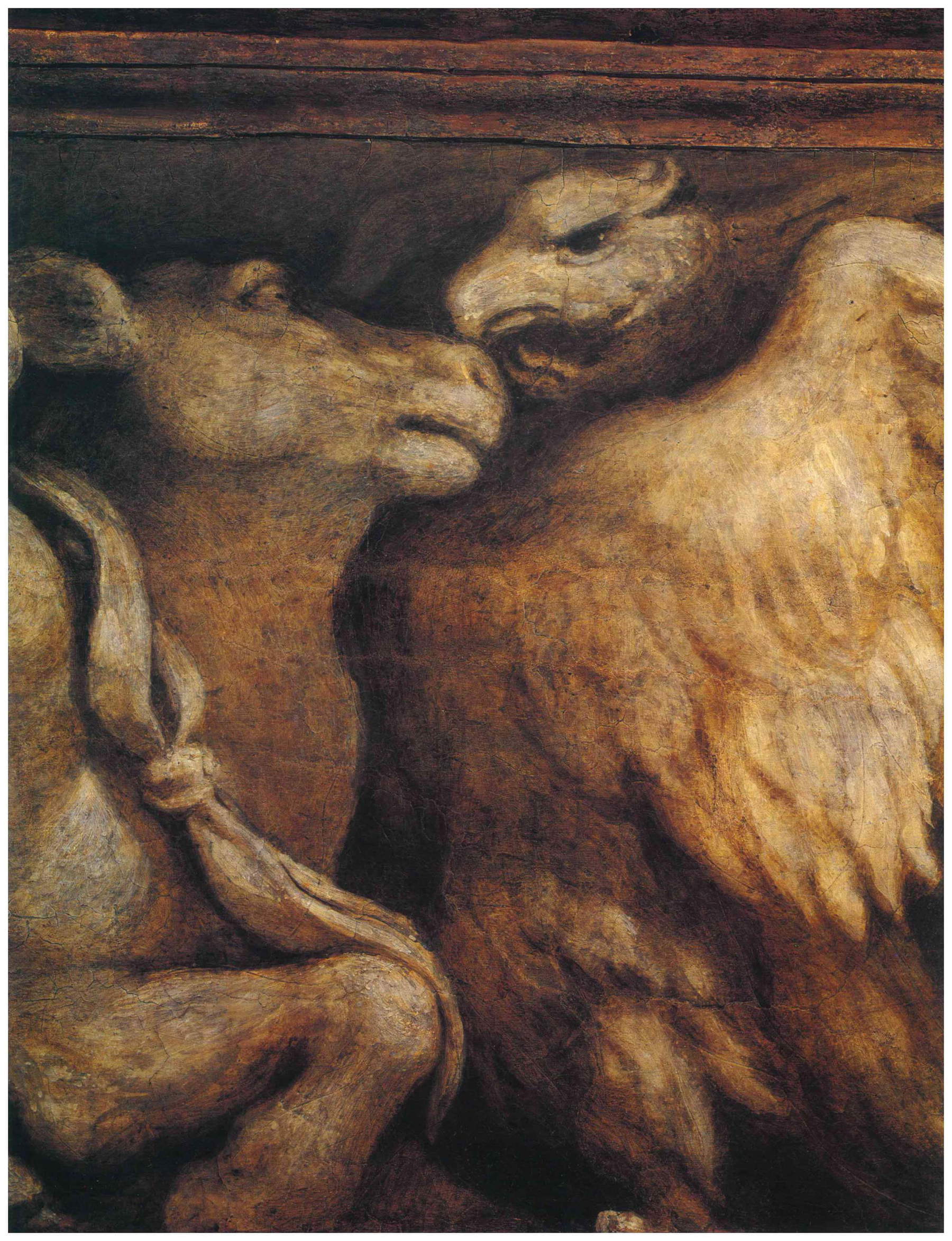

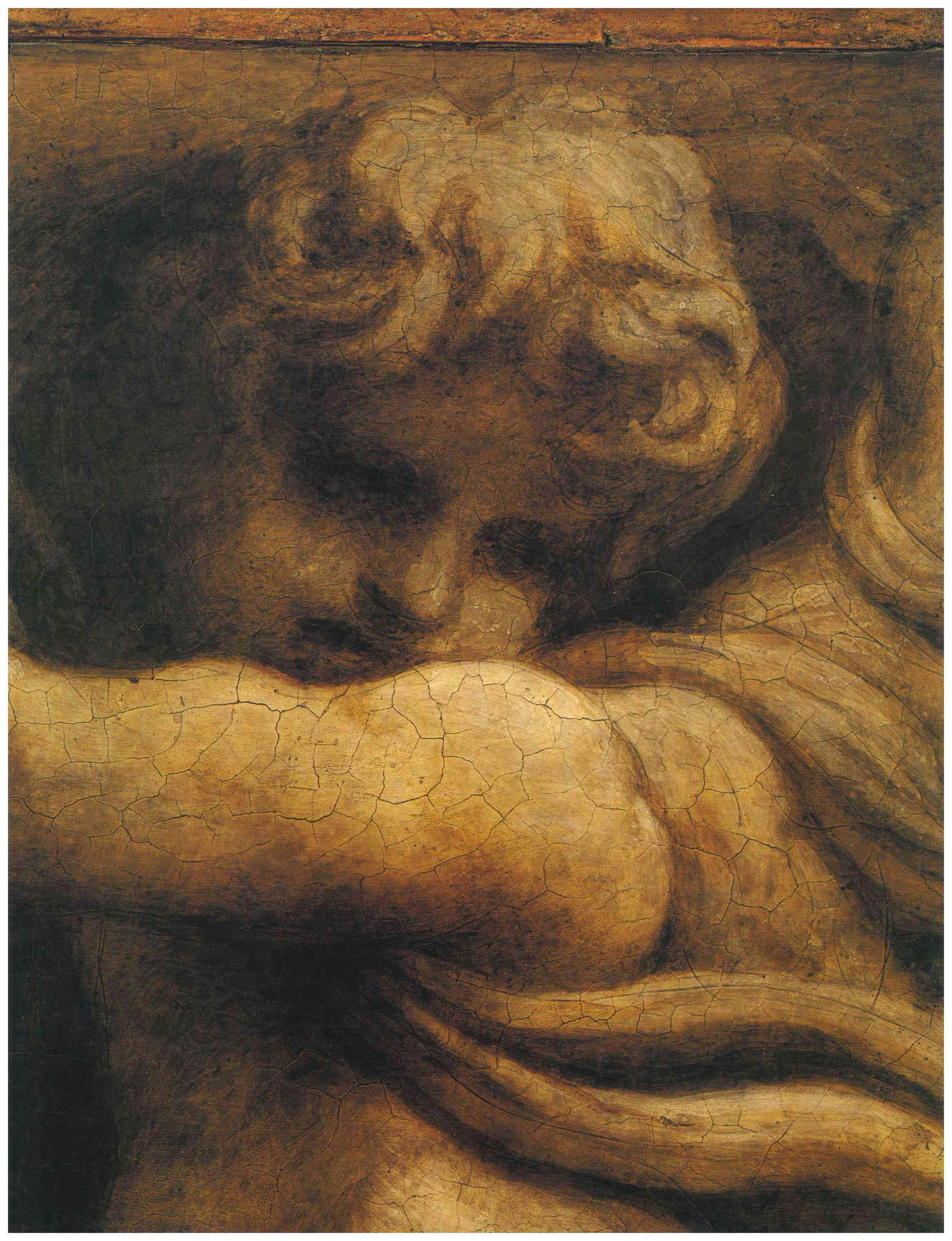

The symbols of the evangelists Luke and John

The symbols of the evangelists Luke and John

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.