by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 31/12/2017

Categories: Works and artists

- Quaderni di viaggio / Disclaimer

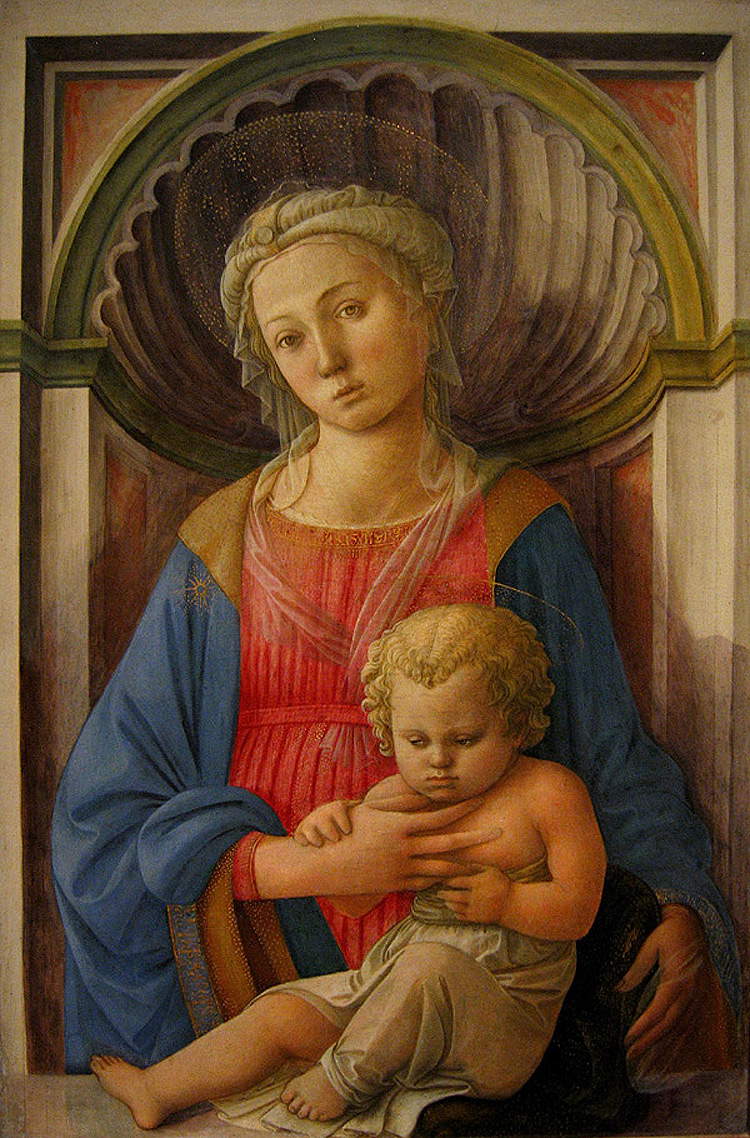

The Museum of Sacred Art in Montespertoli holds a Madonna and Child by Filippo Lippi, a precious masterpiece but a difficult work nonetheless.

If there were to be a ranking of the Italian works of art that have most traveled the world to be displayed in international exhibitions, then probably the Madonna and Child by Filippo Lippi (Florence, 1406 - Spoleto, 1469) preserved at the Museum of Sacred Art in Montespertoli could aspire to a place in a hypothetical top ten. In the past seven years alone, the table from the small museum located among the rolling hills of Valdelsa has left the premises of the rectory of San Piero in Mercato, where the gallery is based, to leave for Hungary, France, Japan, and, of course, to travel to other Italian cities as well. Sometimes for exhibitions that are far from memorable, of course: but the interest that the painting arouses certifies its importance, corroborated also by critical events that have seen art historians of the highest level arguing around a work that, stylistically, is not of the smoothest.

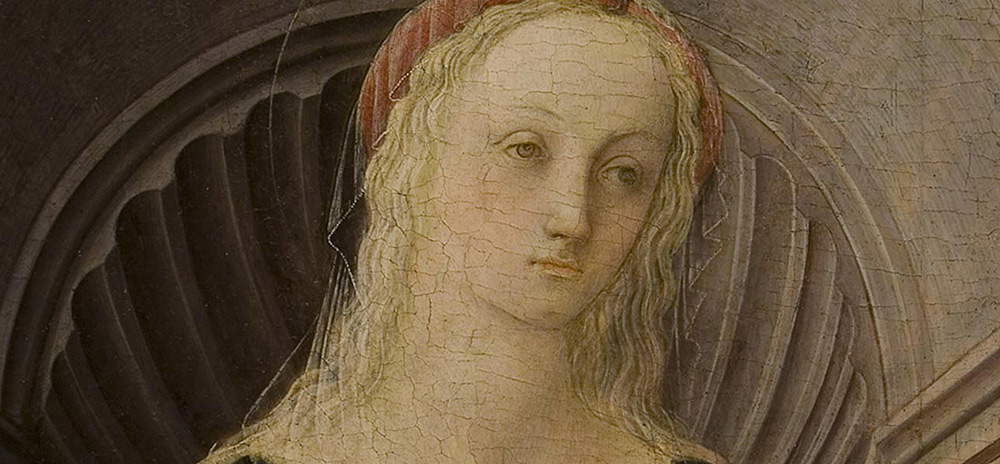

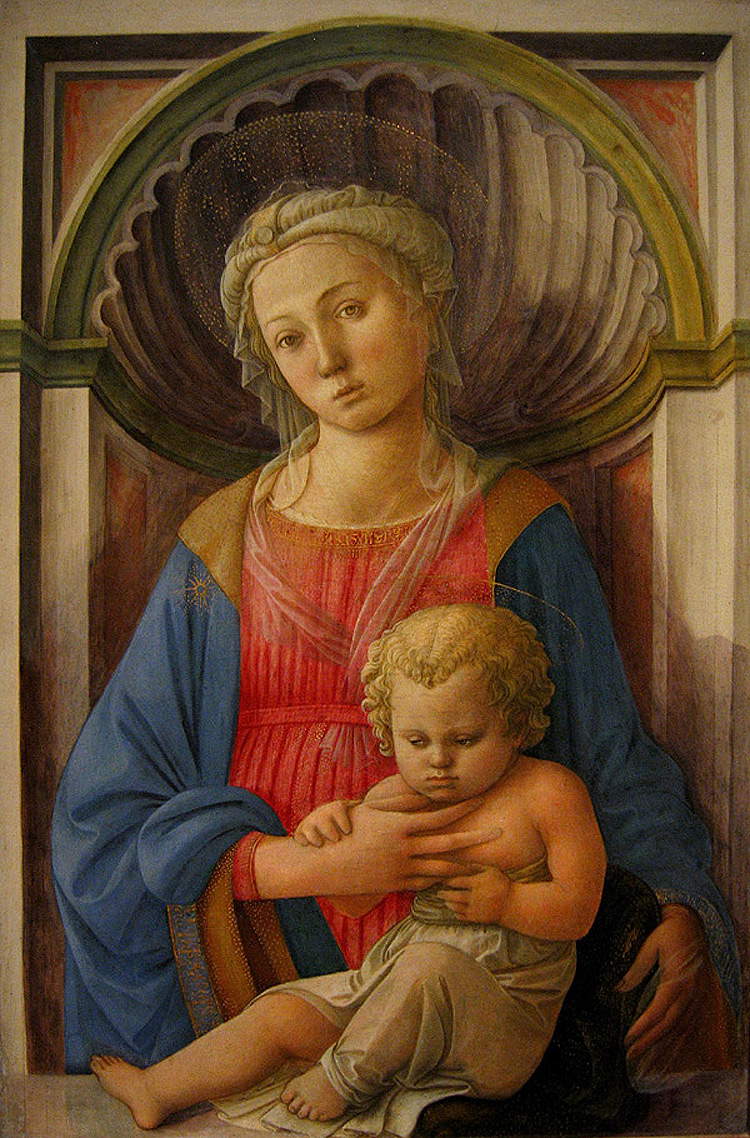

On the contrary, from a purely iconographic point of view, perhaps few other Madonnas are as simple as this one. The Virgin is seated on a niche throne, with the basin in the shape of a shell, as was in use in Renaissance art: a motif taken from classical art, and to which, at the time, was attributed a renewed Christian significance connected to Mary’s virginal conception (the pearl, according to ancient beliefs, was the fruit of the shell born without the need for male fertilizing intervention) but also to the resurrection (the image of the shell opening and generating the pearl could be compared to that of the sarcophagus that opens in order to allow Christ to rise again). The figure of the Madonna takes on monumental tones common to other paintings by Filippo Lippi; she has a gaze that seems almost lost and crossed by a motion of melancholy, and with her hands she holds the Child on her lap: the baby Jesus is still in swaddling clothes, and is gently supported by his mother, who makes his head rest on a brocade pillow. Note the naturalism of the little one, who with his viscous gaze almost seems to want to communicate his displeasure with the swaddling clothes that hold him and prevent his movements (swaddling clothes, moreover, rendered with a certain technical skill: look at the shading between the folds). The red border, the typical color of coral, is interesting: it almost seems as if the artist, with this expedient, wanted to somehow “replace” the sprig of coral that, as per the iconography, was hung around Jesus’ neck (it was an established custom to adorn newborn babies with such an object since in ancient times it was considered a sort of amulet capable of protecting the infant). The Virgin is clothed according to the most traditional iconography: a red dress (the color associated with the earth, and thus a symbol of Our Lady’s humanity, but also the color of Christ’s blood shed on the cross and thus an allusion to his sacrifice) covered by a blue mantle (the color of heaven, signifying Mary’s divine nature) and encircling her head is a transparent veil that allows a glimpse of her blond hair. The only concession to the fashion of the time is the red sash Our Lady wears on her head, in use among the women of 15th-century Florence. A concession, however, that was justified: it was meant to offer a reference to the everyday life of the devotee who was to worship the work.

|

| Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child (c. 1450; tempera on panel, 89 x 64 cm; Montespertoli, Museum of Sacred Art) |

|

| Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child of Montespertoli, detail of the face |

|

| Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child in its location in Montespertoli |

|

| The room in the Museum of Sacred Art in Montespertoli that houses the work by Filippo Lippi |

It has not been easy to confidently place the Madonna and Child within Filippo Lippi’s artistic career: doubts still remain about the dating of the work, as well as the actual extent of the master’s interventions. And in the past, the work was not even attributed to the great Florentine artist. The first scholar to deal with the panel, Guido Carocci, believed it to be the work of Fra’ Diamante. It must be said that, at the time, the painting was in a less than optimal state of preservation, which had obscured its very high quality (also because it must also be considered that until 1933 the work was covered with some ex-votos, namely a crown on the Madonna’s head and some precious metal inserts on the body of the Infant Jesus, later removed): only in 1963 did the restoration to which the panel was subjected bring out its exceptional nature. However, despite its state of preservation, it did not take long for someone to guess that it was a work by Lippi: in 1933 Giorgio Castelfranco curated an Exhibition of the Treasure of Sacred Florence, in which the Montespertoli panel was recognized as a work by Filippo Lippi, made around 1450, at a date close to that of the Tondo Bartolini now preserved in the Palatine Gallery of Palazzo Pitti (thus at a mature stage of the artist’s career). Nonetheless, there were those who continued not to consider the Montespertoli panel a product of the master’s hand: art historians such as Richard Offner, Georg Pudelko (for whom it might have been the work of an unspecified “Scolaro di Prato”), Robert Oertel and Mary Pittaluga assigned it to the workshop, and Bernard Berenson, who first accepted Castelfranco’s hypothesis, later preferred to ascribe the work to the inspiration of Zanobi Machiavelli. In all cases, however, these were contributions that came before the decisive 1963 restoration conducted by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure.

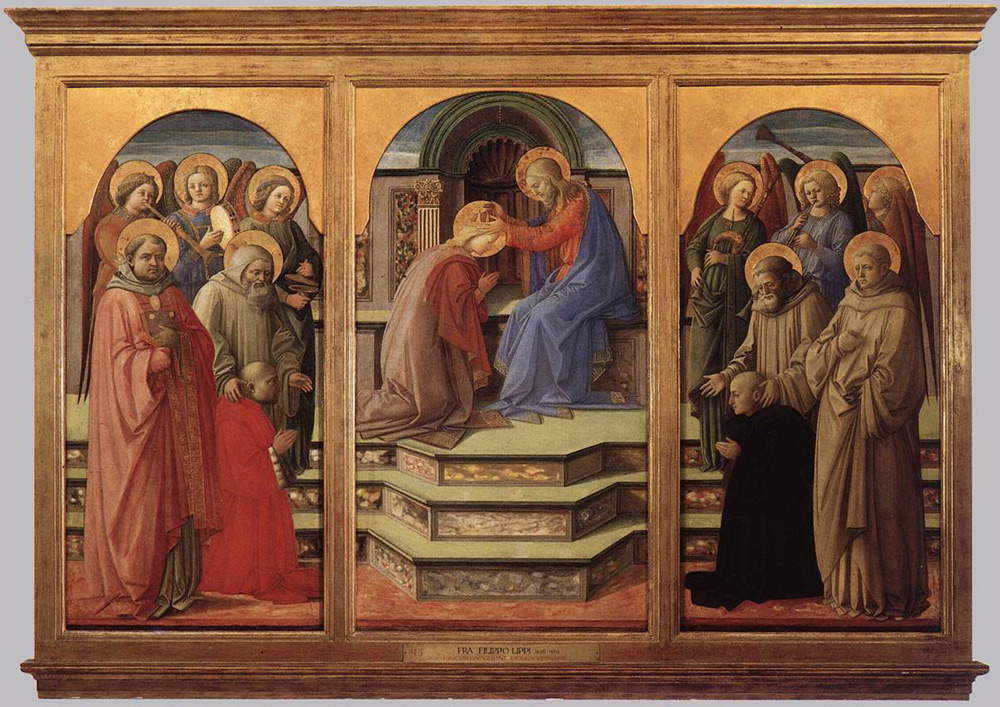

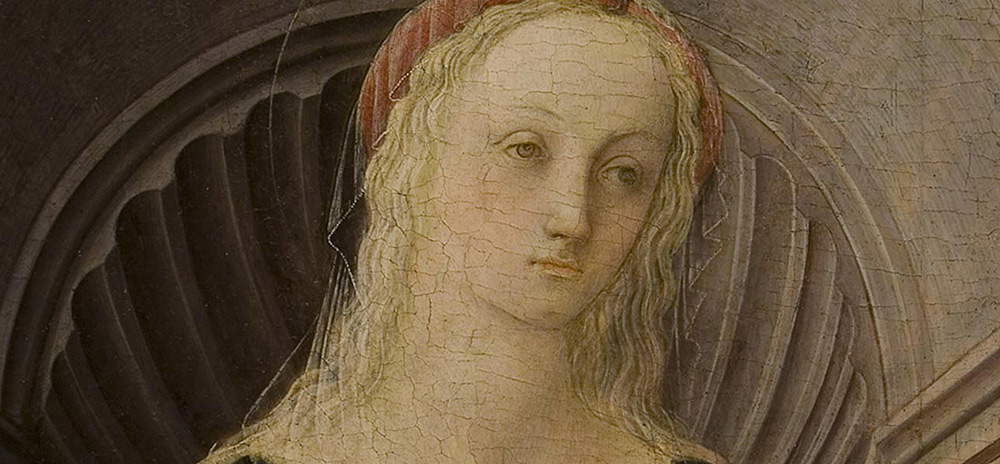

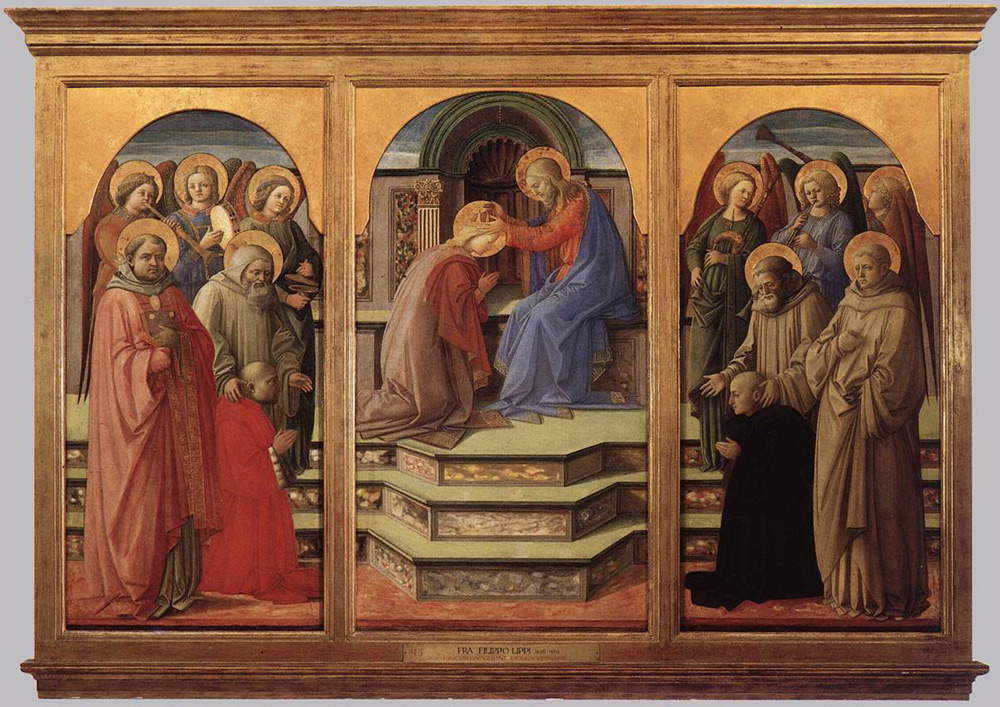

The eminently Lippesque quality of the work was ascertained precisely as a result of the intervention. The style of the master, though weaker than in his other achievements (so much so that there are hypotheses that it might be a work executed with the help of the workshop, or a workshop work on which Filippo Lippi then intervened towards the final stages), is nevertheless recognizable without too much difficulty: the great lyricism that connotes the two figures, especially that of the Madonna, the fineness of the sign (immediately clear if one observes the Madonna’s veil), and the naturalism of certain details (beginning precisely with the bands that wrap around the Child) are characteristics proper to Filippo Lippi’s style, so much so that many scholars who analyzed the painting immediately after the restoration (at least Paolo Dal Poggetto and Federico Zeri should be mentioned) had no doubts about the painting’s authorship. To all this must then be added the similarities between the Montespertoli panel and other works by Filippo Lippi. Among the works that come closest to it, it is possible to mention the Madonna and Child preserved at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore, the one in the Medici-Riccardi Palace in Florence, the one in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the aforementioned Tondo Bartolini, and theDoria Annunciation (a juxtaposition, the latter, proposed by Andrea De Marchi). One of the last art historians to have dealt with the painting, Jeffrey Ruda, author of a monograph on Filippo Lippi published in 1993, also wanted to try to establish a comparison between the architecture within which the figures of the Madonna and Child find space, and the structure of the so-called Marsuppini Coronation now preserved in Rome at the Pinacoteca Vaticana: the niche surmounted by a shell and covered with marble panels had in fact appeared to the American scholar to be a “simplified version” of that present in theCoronation. But that’s not all: Ruda also suggested a comparison between the Montespertoli panel and theMaringhi Coronation, hypothesizing links between the face of the Madonna of Montespertoli and that of the angels who appear in the painting preserved in the Uffizi.

|

| Filippo Lippi, Tondo Bartolini (c. 1452-1453; tempera on panel, diameter 153 cm; Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Palatine Gallery) |

|

| Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child (c. 1440; tempera on panel, 79 x 51.1 cm; Washington, National Gallery of Art) |

|

| Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child (c. 1446-1447; tempera on panel, 127 x 87 cm; Baltimore, Walters Art Museum) |

|

| Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child (c. 1466; tempera on panel, 115 x 71 cm; Florence, Medici-Riccardi Palace) |

|

| Filippo Lippi, Doria Annunciation (c. 1466; tempera on panel, 118 x 175 cm; Rome, Doria Pamphilj Gallery) |

|

| Filippo Lippi, Coronation of the Virgin with Angels and Saints known as the Marsuppini Coronation (after 1444; tempera on panel, 172 x 251 cm; Rome, Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Pinacoteca Vaticana) |

|

| Filippo Lippi, Coronation of the Virgin called the Maringhi Coronation, detail of the angels (1439-1447; tempera on panel, 200 x 287 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

Ruda then provided other interesting suggestions of an iconological kind (particularly on the figure of the Child, whose pose alludes to that of Christ in piety, and one might also add that his body so tightly wrapped in swaddling clothes recalls the moment of his burial after the Passion: these are in any case typical references to the last events of Christ’s life) and especially of a stylistic kind. In particular, the art historian believed that the drawing was rather weak: “the Madonna’s head is small in proportion to her body, her pose is vague even assuming losses in modeling, and the Child’s pose is awkwardly compromised between the second and third dimensions.” For these reasons, Ruda put forward the hypothesis that the Montespertoli panel was the work of a workshop, while admitting the plausibility of an intervention by Filippo Lippi in the last stages of its realization. In 1995, Rosanna Caterina Proto Pisani, in the catalog of the Museum of Sacred Art in Montespertoli, suggested that the work might instead constitute a “delightful masterpiece of the artist’s late period,” corroborating the hypothesis with what Paolo Dal Poggetto wrote in 1963: according to the scholar, the work represents “one of the rare moments in which Lippi at the end of his long elaborations could contemplate the melancholy sweetness of the rhythmic images immersed in the pale and long pause of a gray enclosure.” And again, in 2009, in the catalog of the exhibition on Filippo and Filippino Lippi at the Musée de Luxembourg in Paris, Maria Pia Mannini pointed out that “this Madonna testifies to the virtuosity typical of the painter, especially in the lively gaze of the Child and in his restless expression that recalls the curious physiognomies of Paolo Uccello in the chapel of the Assumption in the cathedral of Prato and that likewise would influence later generations (Pontormo).”

As for the dating, having discarded the idea of a youthful work (so thought Pietro Toesca, who wrote about it in 1934), the hypotheses oscillate between 1440 and 1450 (lately, however, there is a tendency to shift it to around 1450): we are in any case in a mature phase of Filippo Lippi’s art, engaged in a work that was probably intended for a place outside Florence, although we cannot establish anything with certainty, in the absence of documentary evidence. The work is first attested in the church of Sant’Andrea in Botinaccio, a small hamlet of Montespertoli, and was moved to the local Museum of Sacred Art for conservation reasons. However, there is no reason to doubt that the work was painted specifically for the Botinaccio church. Today, however, the public can admire the “gem” of the Museum of Sacred Art of Montespertoli (as Rosanna Caterina Proto Pisani nicknamed it) in the Yellow Room of the museum, about halfway through a journey among the works of the area: a journey full of charm, of which Filippo Lippi’s Madonna represents the culmination of poetry and delicacy.

Reference bibliography

- Cristina Gnoni Mavarelli, Maria Pia Mannini (eds.), Filippo et Filippino Lippi. La Renaissance à Prato, exhibition catalog (Paris, Musée du Luxembourg, March 25 to August 2, 2009), Silvana Editoriale, 2009

- Rosanna Caterina Proto Pisani (ed.), Museo d’Arte Sacra di Montespertoli, Edizioni Polistampa, 2006

- Maria Pia Mannini, Marco Fagioli, Filippo Lippi. Complete catalog, Octavo, 1997

- Rosanna Caterina Proto Pisani, Antonella Nesi (eds.), The Museum of Sacred Art in Montespertoli, Becocci/Scala, 1995

- Jeffrey Ruda, Fra Filippo Lippi. Life and work with a complete catalogue, Phaidon Press, 1993

- Paolo Dal Poggetto (ed.), Arte in Valdelsa, exhibition catalog (Certaldo, Palazzo Pretorio, July 28 to October 31, 1963), STIAV, 1963

- Giorgio Castelfranco (ed.), Mostra del Tesoro di Firenze Sacra, exhibition catalog (Florence, Convento di San Marco, 1933), Tipocalcografia Classica, 1933

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.