The celebrated French writer and poet Raymond Queneau (Le Havre, 1903 - Paris, 1976) coined in 1949, in his essay Joan Miró ou le poète préhistorique, a new term to refer to the pictorial works of the Catalan artist Joan Miró (Barcelona, 1893 - Palma de Mallorca, 1983): miroglific. According to Queneau, constant signs and elements recurred in the latter’s production, going so far as to claim that Miró was “a language that one must learn to read and of which it is possible to fabricate a dictionary.” Similar to hieroglyphs, mirós, as characters of an ideographic script, could be associated with objects or ideas, translatable through an alphabet or a convention dictionary to refer to.

However, Queneau’s project of fabricating a true myrogliphic dictionary remained only an idea, as he ignored the existence of a significant repertoire of drawings that the artist had handed over in 1975 to the Fundació in Barcelona, established by himself: nearly five thousand sketches, sketches, fragmentary proofs, in-depth sketches, studies and preparatory sketches of works in which enunciative writing was evident.

What Miró practiced was indeed a language of signs, a reciprocal exchange between image and word, possessing a grammar, a syntax and a dictionary of figures.

“Miró’s painting is a writing that one must know how to decipher,” Queneau asserted, pointing out that one of the artist’s paintings could be read like a poem: “A poem must be read in its original language; one must learn Miró, and once one knows (or thinks one knows) Miró, one can set about reading his poems.” That is, his pictorial compositions.

It is necessary to remember that Miró himself presented the semiological character of his works, implying that the signs imprinted on his canvases always referred to concrete forms, as elements of a verbal language: “For me a form is never something abstract; it is always the sign of something. For me, painting is never form for form’s sake.”

Approaching the Surrealist movement since 1924, the year of the First Manifesto of Surrealism, Miró was undoubtedly affected byautomatism, making his art free, spontaneous; sometimes, at first glance, it can be considered easy, frivolous: André Breton (Tinchebray, 1896 - Paris, 1966) himself declared that the Catalan artist’s personality “stopped at the infantile stage,” but it is precisely that psychic andcreative freedom that is the founding character of Surrealism. His forms refer toinnocence, whimsy, worlds and characters that belong to a personal universe, but everything is immersed in a context of grace and harmony. His is a world bordering on magic: in front of his paintings, the viewer is suddenly catapulted into imaginative scenes and finds himself strolling inside the depicted scenes and meeting the funny protagonist figures. It is a colorful world, where a wide variety of bright tones, from yellows to blues, greens and reds, with the presence often of black and white, create harmonious and sometimes geometric compositions. In addition to colors, in fact, one can recognize in Miró’s canvases triangles, circles, rhombuses, squares that become faces or other parts of a body, animals, natural elements or objects. The signs and shapes he depicts on the canvas are nothing more than images that arise from his mind, but above all from his unconscious, and that he lets out through his creative ability in a playful alphabet, in a painting-writing that is never negative.

It is characteristic of Surrealism to believe in theomnipotence of dreams, in the disinterested play of thought, which become higher realities; indeed, the definition given by the movement’s founder André Breton states that Surrealism is the pure psychic automatism by means of which one proposes to express either verbally, in writing or in other ways, the real functioning of thought; it is the dictation of thought, with absence of all control exercised by reason, beyond all aesthetic and moral concerns. The Catalan painter’s canvases could be called for this reason images of dream and color, where the creative and playful element is central.

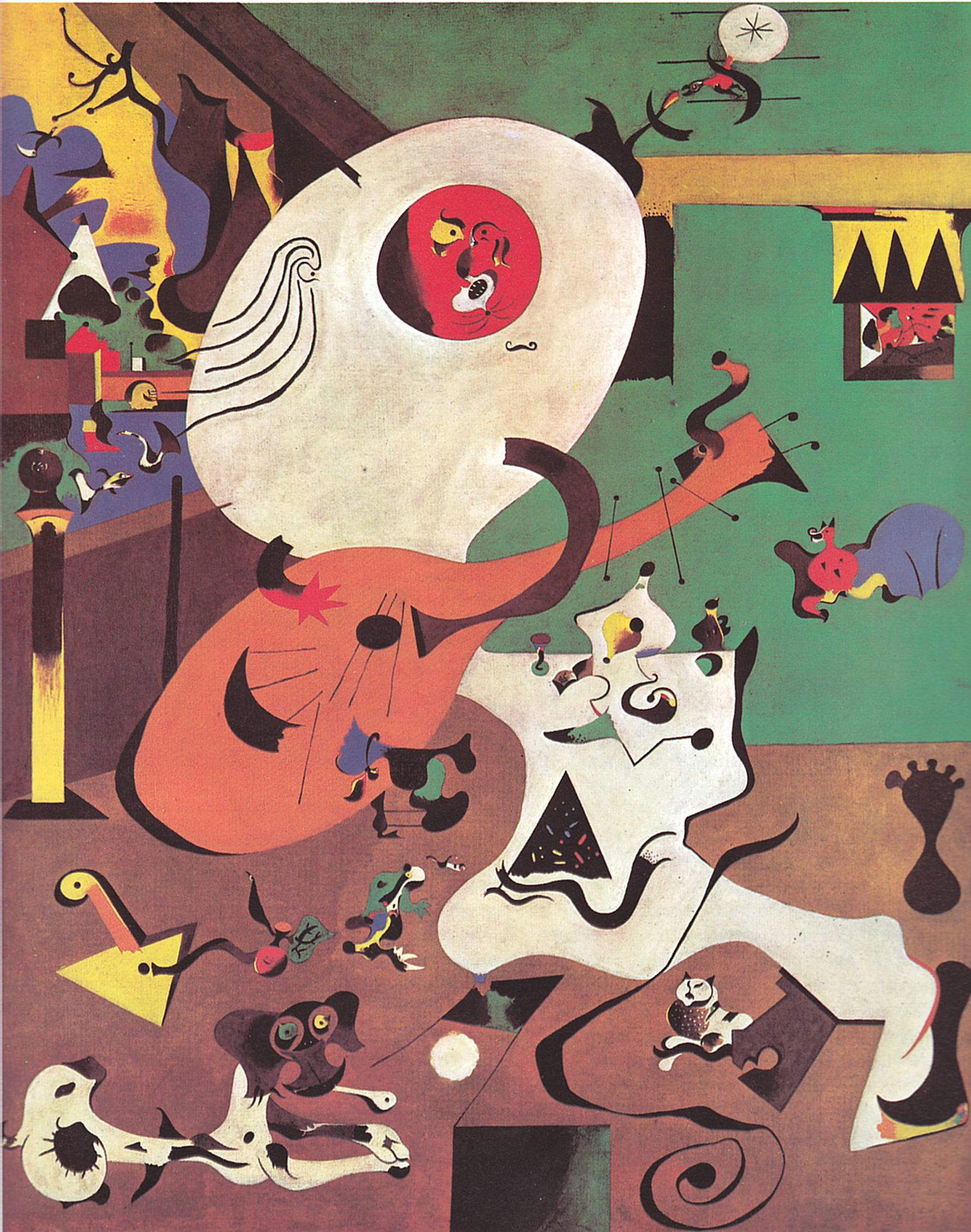

It is between 1924 and 1929 that Joan Miró’s style was characterized by broad expanses of color on which arabesque lines stand out to form his funny characters of invention: significant in this sense is Harlequin’s Carnival, a painting made in 1924, and the so-called Dutch Interior series . Referring to The Carnival of Harlequin and TheHermitage, both from the same year, the poet and writer Louis Aragon (Paris, 1897 - 1982) stated, “Perhaps it is here that anti-paintering begins and that novel writing is born, which, disclosed as if at the end of a prehistory spent in caves, finally comes out to meet the hieroglyphic sense of the world and establishes the greatest contrast between the violence of colors and the claims of the sign.”

|

| Joan Miró, Harlequin’s Carnival (1924-1925; oil on canvas, 66 x 93 cm; Buffalo, Albright-Knox Art Gallery) |

|

| Joan Miró, Hermitage (1924; oil, pencil and graphite on canvas, 114.3 x 146.2 cm; Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art) |

|

| Hieronymus Bosch, Triptych of the Garden of Delights, central panel (1490-1500; oil on panel, height 205.5 cm; Madrid, Prado Museum) |

Harlequin’s Carnival recalls the canvases of Bosch (’s-Hertogenbosch, 1453 - 1516), an ancient master of the fantastic, as they too are populated by funny, tiny creatures born of his inventive skill and immersed in bizarre scenarios that seem to have sprung from dream worlds. Miró’s famous painting preserved at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo depicts an indoor environment in which little beasts from the animal world float around and relate to various objects: colorful cats, an homage to the one he kept close to him when he was painting, a fish, a fly coming out of a nut, and some recurring symbols are recognizable, such as the ladder ladder evoking escape from the world, the black sphere on the right indicating the globe, the triangle sticking out of the open window that would represent the Eiffel Tower (he was staying in Paris at the time), the man in the center with a mustache smoking a pipe; and again musical instruments and notes hinting at the cheerful atmosphere of Carnival, a star and the artist’s eye hunting for motifs to introduce into his art.

The aforementioned Dutch Interiors, on the other hand, originate from Dutch paintings that the artist has the opportunity to admire in their homeland. They are a series of three paintings inspired by Dutch painting of the seventeenth century: Dutch Interior I reinterprets the lute player depicted by Martensz Sorgh (Rotterdam, 1610-11 - 1670) in 1661, Dutch Interior II is inspired by JanSteen ’s (Leiden, 1626 - 1679) Dancing Lesson of 1665, and finally Dutch Interior III depicts a young woman at the bath in which elements of Sorgh and Steen are interwoven.

|

| Joan Miró, Dutch Interior I (July-December 1928; oil on canvas, 91.8 x 73 cm; New York, MoMA - Museum of Modern Art) |

|

| Joan Miró, Dutch Interior II (summer 1928; oil on canvas, 92 x 73 cm; New York, Guggenheim Museum) |

|

| Joan Miró, Dutch Interior III (1928; oil on canvas, 129.9 x 96.8 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| Hendrick Maertenszoon Sorgh, The Lute Player (1661; oil on panel, 52 x 39 cm; Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum) |

|

| Jan Steen, Dancing Lesson (1660-1679; oil on panel, 68.5 x 59 cm; Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum) |

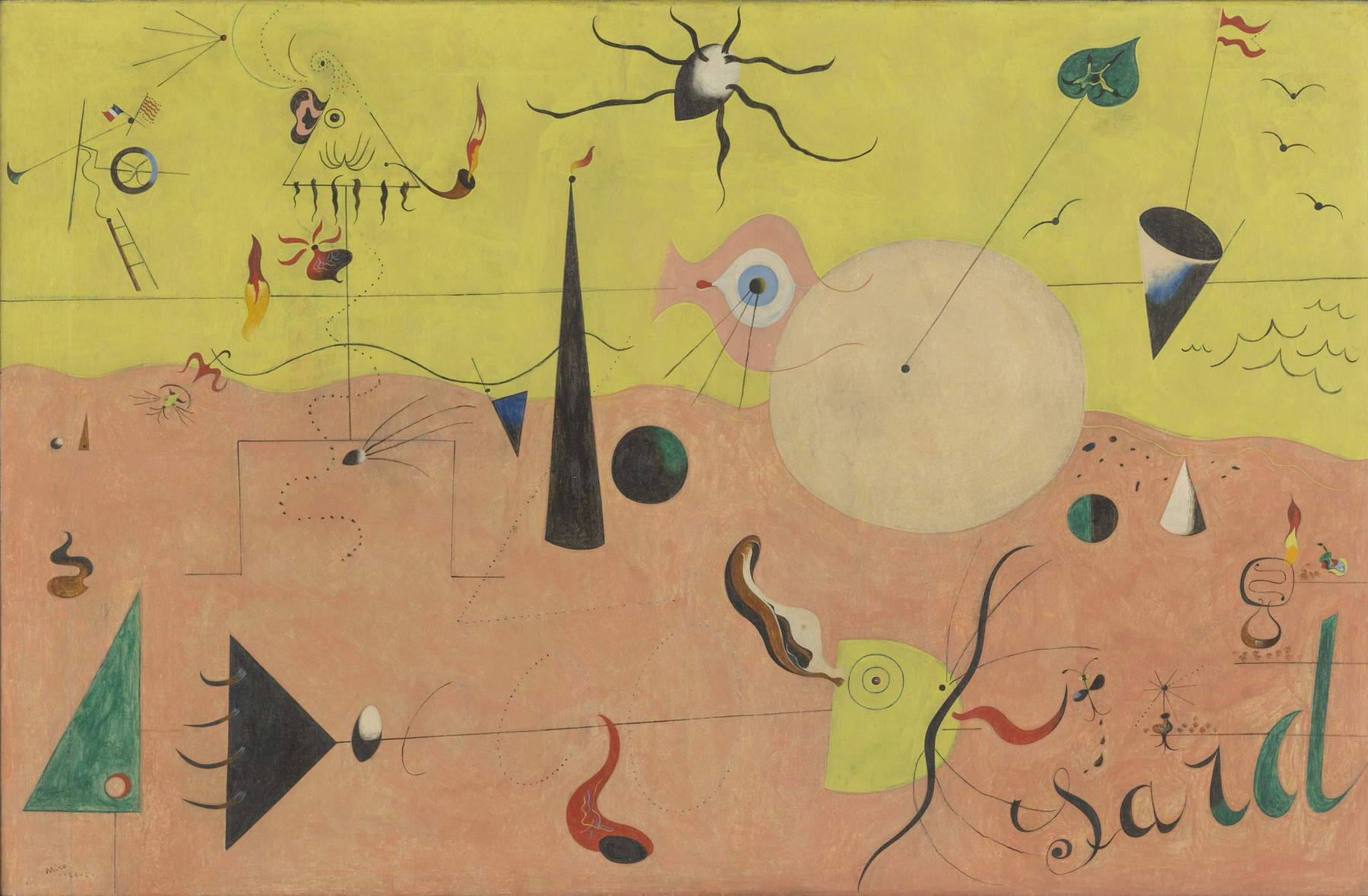

The previously mentioned geometric composition is clearly evident in the 1924 Hunter, otherwise known as Catalan Landscape. The hunter, depicted in the upper left, has a beard, mustache, pipe, heart, and genital organ, and his body is stylized, with a triangle serving as his head and a wide-open eye; the curved line running horizontally from the middle of his body implies the movement of circumspection with which the man goes in search of game. The close eye and ear emphasize the auditory and visual alertness with which the hunter prepares for his activity. The hunter has been read as a metaphor for the artist: like a hunter in search of prey, the latter moves through the world, searching for symbols and metaphors that adequately represent his worldview. Painting therefore is a kind of hunting, and for that reason sight is a primary need for the artist, as evidenced by the large eye in the center of the composition. Significant element to note is the presence of the Catalan flag next to the French flag in the left end of the painting, under which a small ladder can still be seen, while in the right end waves the Spanish flag on a pole stuck in a cone. His homeland, Catalonia, is evoked in this painting not only by the flag but also by the word Sard that appears in the lower right, a probable allusion to the sardana, a typical Catalan dance. Miró began to include words in his compositions as elements alluding to certain concepts, but the presence of the three Catalan, French, and Spanish flags is also found in The Plowed Field, a painting made between 1923 and 1924 that is housed in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, probably implying an alliance of peoples, geographies, and cultures.

|

| Joan Miró, Hunter (Catalan Landscape) (1924; oil on canvas, 64.8 x 100.3 cm; New York, MoMA - Museum of Modern Art) |

|

| Joan Miró, Plowed Field (1923-1924; oil on canvas, 66 x 92.7 cm; New York, Guggenheim Museum) |

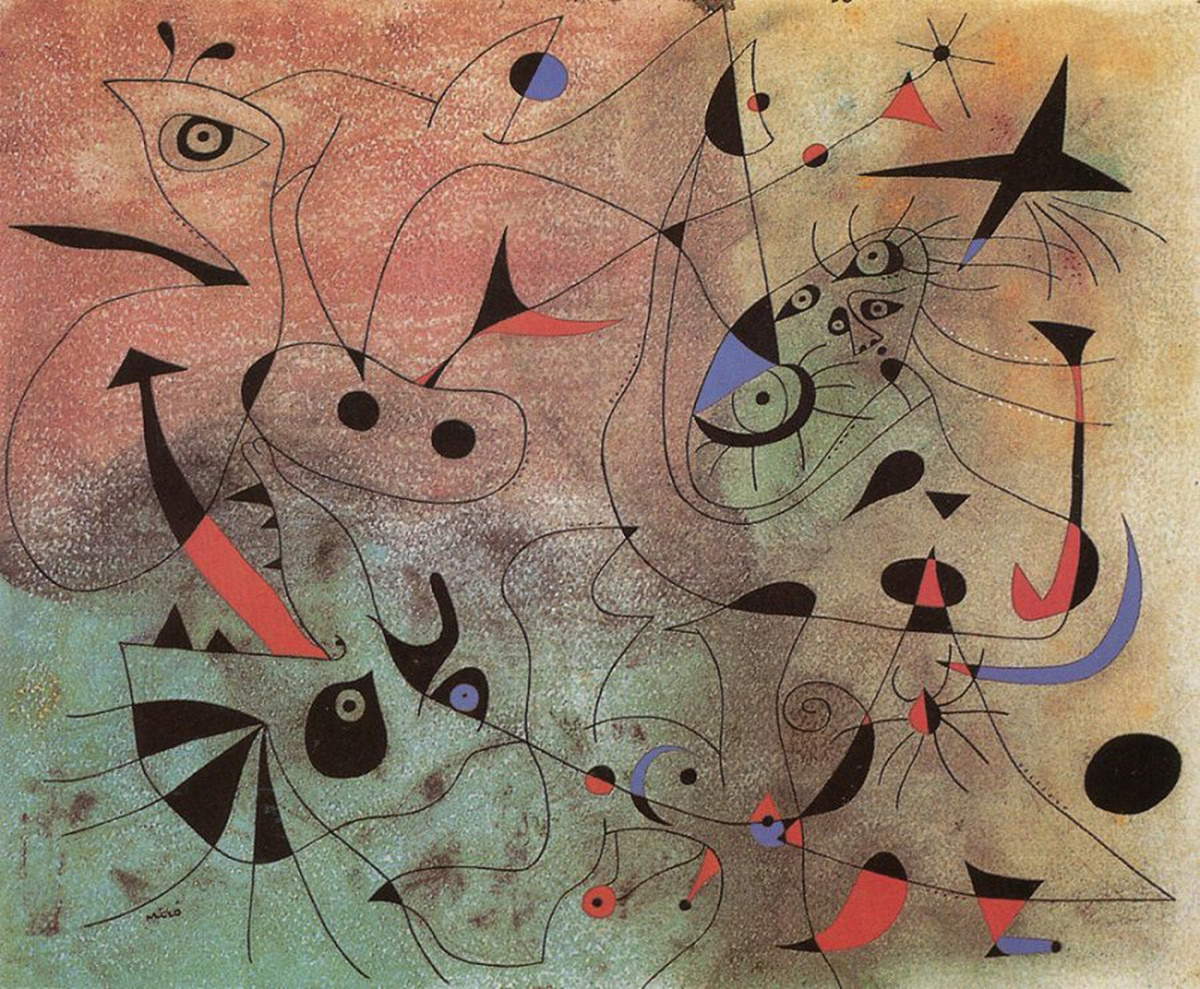

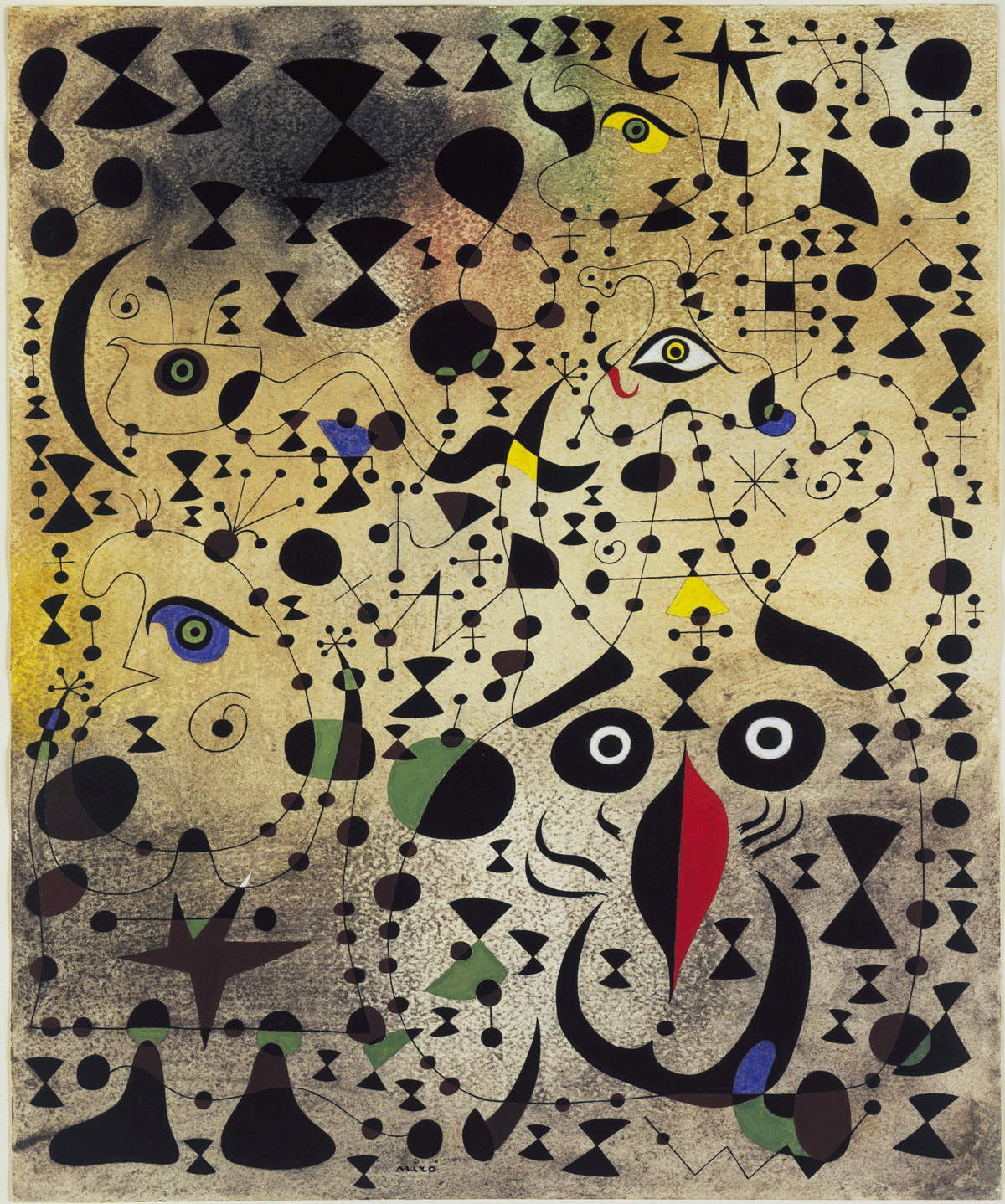

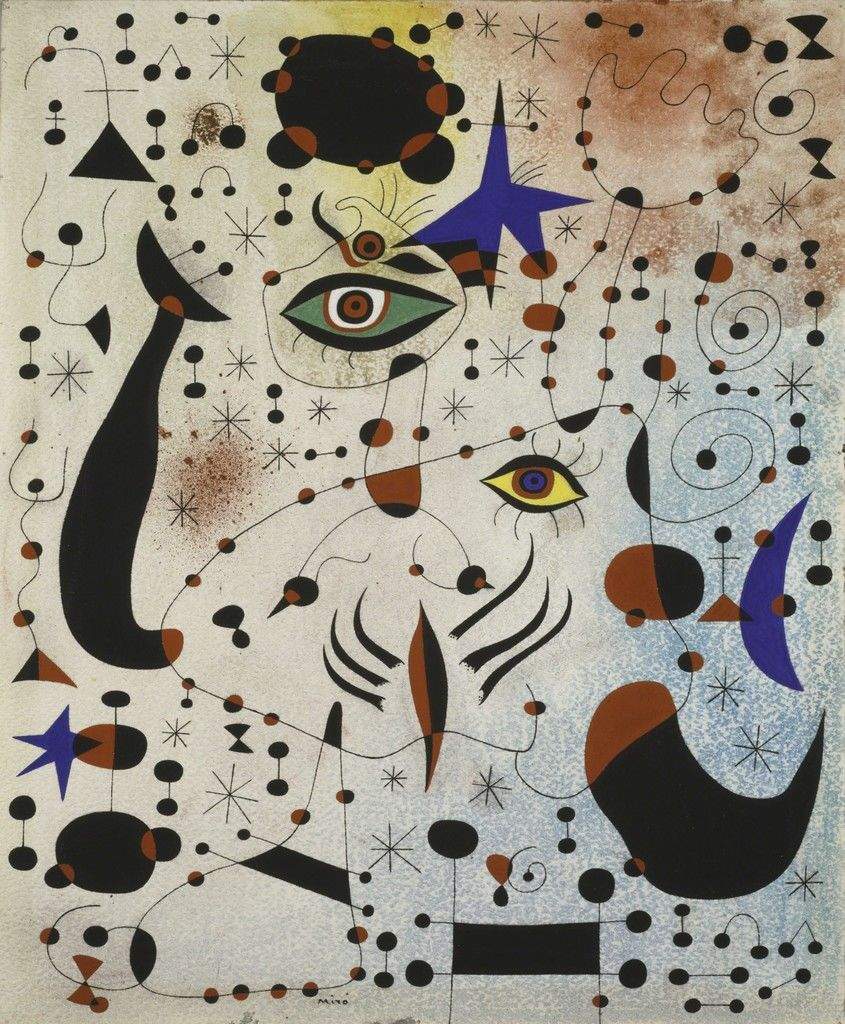

The interest in ideographic painting did not stop with the end of the 1920s; on the contrary, it continued until it became one of the most prominent features of Miró’s art, evolving to the Constellations series, begun in January 1940. A series of twenty-three tempera paintings on paper that testifies to the artist’s fascination with the stars and the sky. On shaded backgrounds one notices more or less geometric shapes that combine in very striking paintings: it really seems as if one is admiring fantastic portions of the sky; as when at night, with one’s gaze turned toward the sky, one tries to identify the various constellations and shapes that the bright stars compose. In this series one can recognize eyes, moons, stars, globes forming figures of animals and people: thick strokes made using black very often outline these recognizable shapes, but red, green, yellow, and blue are present, giving dense touches of color to the particular compositions. The artist knew the sky well, because as a child he enjoyed with his father observing every little part of it through a telescope.

The titles chosen for each painting in the Constellations series are also very poetic and narrate the depicted scene in a few words: they were probably inspired by poetry itself, which Miró was passionate about, but especially by music; poetry and music, as well as painting, helped him through the tragic nature of the war, from which he distanced himself first by moving in 1938 to Varengeville-sur-Mer, on the Normandy coast, and later, following the invasion of France by German troops, he returned to Spain in 1940, settling in Palma de Mallorca.

|

| Joan Miró, Song of the Midnight Nightingale and Morning Rain, from the series Constellations (1940; gouache and terpentine painting on paper, 38 x 46 cm; New York, Perls Galleries) |

|

| Joan Miró, Morning Star, from the series Constellations (1940; gouache and terpentine painting on paper, 38 x 46 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Joan Miró, Beautiful Bird Reveals the Unknown to a Loving Couple, from the series Constellations (1941; gouache, oil and charcoal on paper, 45.7 x 38.1 cm; New York, MoMA - Museum of Modern Art) |

|

| Joan Miró, Figures at Night Guided by Phosphorescent Slug Tracks, from the series Constellations (1940; watercolor and gouache on paper, 37.9 x 45.7 cm; Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art) |

|

| Joan Miró, Numbers and Constellations in Love with a Woman, from the series Constellations (1941; watercolor on paper, 45.9 x 38 cm; Chicago, Art Institute) |

Song of the Midnight Nightingale and Morning Rain, Morning Star, The Beautiful Bird Reveals the Unknown to a Loving Couple, Figures at Night Guided by Phosphorescent Slug Tracks, Numbers and Constellations in Love with a Woman are some of the titles in this series.

The deep blue of the sky dominates in Figures at Night Guided by Phosphorescent Slug Tracks, precisely indicating the painting’snighttime setting , where the large white moon in the top center is also clearly recognizable; the figures mentioned in the title, on the other hand, are characterized by large, wide-open eyes. Both the head and the body suggest that they are figures of invention, which do not exist in reality. Somewhat as in all the other paintings mentioned: the midnight nightingale singing in the related work is probably high up in the center of the composition, recognizable by its open crescent-shaped beak, a sign that it is making a sound, and its long wings. Night is represented here by a few blue stars, while the rest of the composition focuses on red and black tones against a light gray background with shades tending toward yellow. Other figures are present in the work, particularly in the central part and the right end of the painting.

Intersecting figures are the protagonists of Stella del mattino and it sometimes becomes complicated to define their appearance: what one is able to recognize are very often eyes, noses, open mouths with teeth from which long tongues sprout. In the foreground in The Beautiful Bird Reveals the Unknown to a Loving Couple we see a large head equipped with eyes, eyebrows, nose and a smiling mouth; several eyes are scattered throughout the painting, but it is difficult to distinguish the various shapes that stand out this time against a background of different shades of yellow.

The same goes for Numbers and Constellations in Love with a Woman, where the only clearly defined elements are two open eyes with eyelashes, one green and the other yellow, in the center of the composition.

Observing Miró’s works becomes for the viewer a journey under the banner of dream and the fantastic; each element is an affirmation of theartist’s infinite creativity, from which he allows himself to be freely guided by creating surreal and joyful settings, accompanied by touches of bright color that diffuse and bring out the artist’s playful and cheerful stroke from the canvas.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.