It is the only work on a movable support that can be assigned with certainty to Michelangelo Buonarroti (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564): it is the Tondo Doni, the masterpiece preserved at the Uffizi Gallery and created at the behest of one of the richest Florentine merchants of the early sixteenth century, Agnolo Doni, who in 1504 had taken Maddalena Strozzi, also a member of one of the most prominent families in Florence at the time, as his wife. Revealing to us the name of the commissioner is Giorgio Vasari (Arezzo, 1511 - Florence, 1574), who in his Lives (in both the Torrentine and the Giuntina editions) describes the work with such precision as to leave no doubt as to its identification, and moreover presenting it as a fruit of the rich commissioner’s passion for “beautiful things”: “it came will to Agnolo Doni, a Florentine citizen friend of his, so like that who much delighted in having beautiful things, as well of ancient as of modern artisans, to have some thing by the hand of Michele Agnolo, because he began him a tondo of painting which is within it a Nostra Donna, who, kneeling with amendua her legs, raises up on her arms a putto and hands it to Giuseppo who receives it. Where Michael Agnolo makes known, in the turning of the head of the mother of Christ and in keeping her eyes fixed on the supreme beauty of the Son, her marvelous contentment and affection in making that most holy old man part of her. Who with equal love, tenderness, and reverence takes him in, as is well discerned in his countenance, without much consideration. Nor was this sufficient for Michele Agnolo to show more of his art to be very great, so he made in the field of this work many ignudi leaning, standing and sitting; and with such diligence and cleanliness he worked this work, that certainly of his panel paintings, even if they are few, it is held to be the most finished and the most beautiful that can be found.” According to Vasari, therefore, it is Mary who hands the Child to Saint Joseph, while according to modern art historians the exact opposite is true (also due to the fact that one would expect the little one to turn his gaze to the destination rather than to the departure): a possible symbolic allusion to the union between Christ and his Church, symbolized by the Madonna. Moreover, the Aretine does not mention the presence of the little Saint John the Baptist, whom we see on the right, in the background.

Vasari also reports the negotiation over the payment: given its somewhat comical and almost grotesque (and certainly highly charged) character, it seems entirely legitimate to wonder how true the anecdote may be. That is, it seems that Michelangelo wanted seventy ducats for the painting, a considerable sum for the time: consider that when Michelangelo entered the garden of San Marco, the circle of artists supported by Lorenzo the Magnificent, as a very young man, the artist, then a teenager, always according to Vasari received the salary of five ducats a month. Doni considered Michelangelo’s asking price excessive, and offered him forty ducats: Michelangelo, outraged, reportedly refused, and asked at this point for as much as one hundred. The merchant therefore agreed to pay the seventy ducats initially asked for, and the artist, feeling mocked, responded by letting Doni know that he would sell the work only for twice the price originally estimated: one hundred and forty ducats. Vasari thus relates that Doni, in order to have his tondo, had no choice but to shell out the enormous sum demanded by Michelangelo.

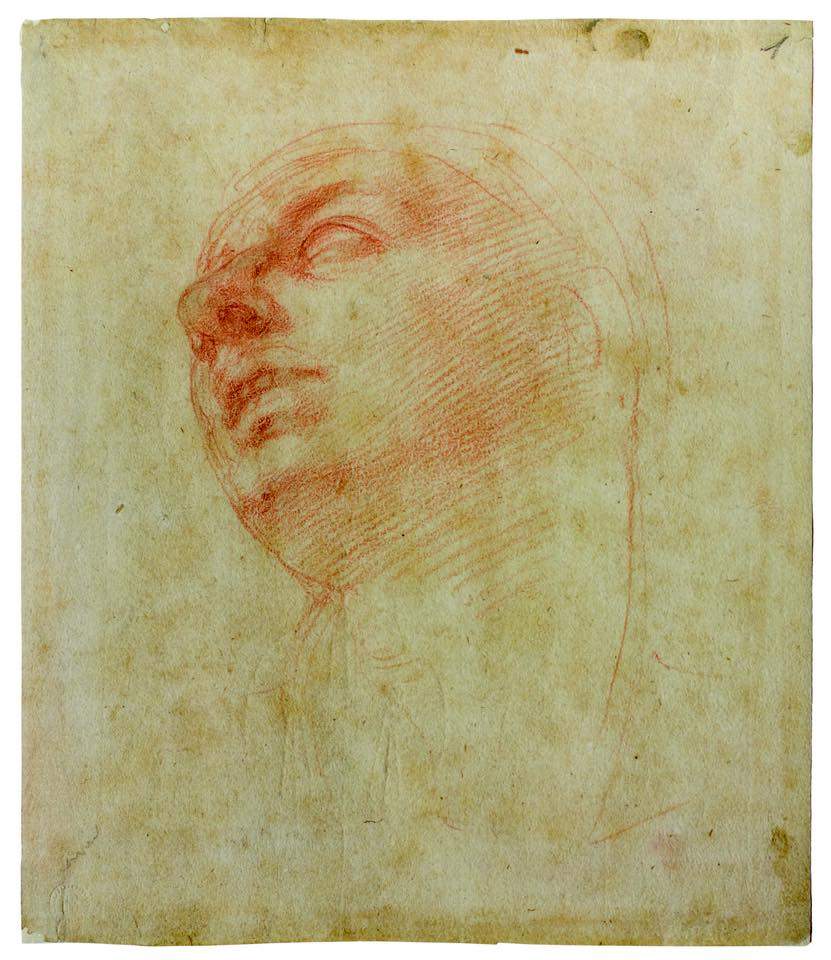

We know for certain that around 1540, the time of the writing of the manuscript known as theAnonimo Magliabechiano, preserved at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence, the painting was still kept in the Doni house: in fact, the text of the anonymous reads of a “tondo di Nostra Donna in casa Agnolo Doni.” However, we do not know under what circumstances it was made. Initially it was thought to have been painted on the occasion of the marriage between Agnolo Doni and Maddalena Strozzi, celebrated in 1504 (in the rich frame executed by the carver Francesco del Tasso, which is still the original one, the three crescents of the Strozzi family coat of arms do in fact appear), but in the 1990s the belief spread instead that the work, in all probability, must have been commissioned to celebrate the birth of the couple’s eldest daughter, Maria, on September 8, 1507. Pushing toward this hypothesis, explained scholar Antonio Natali, had been the “allusions to birth and baptism that we seemed to detect in the iconological warping of the painting,” which therefore, taking for granted a dating to 1507, would slightly precede the Sistine Chapel vault, stylistically akin to the Tondo Doni. “There is no doubt in fact,” Antonio Natali emphasized in his 1995 study, “that the androgynous Virgin Doni belongs to the same heroic and powerful lineage as the Sistine Sibyls, to whom Mary is also related by a physiognomic resemblance; although her features, compared to the somatic features of the Delphic and Libyan, appear gentler.” The close proximity between the Tondo Doni and the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel is also evidenced by a drawing, preserved at Casa Buonarroti, on which critics have been divided between those who consider it a preparatory study for the Virgin in the Tondo Doni, and those who are inclined to consider it an idea for the face of the prophet Jonah in the Sistine Chapel.

|

| Michelangelo, Tondo Doni (1506-1507; tempera grassa on panel, 120 cm diameter; Florence, Uffizi Gallery). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The three half moons of the Strozzi coat of arms on the frame of the Tondo Doni |

|

| Michelangelo, Study for the head of the Madonna of the Tondo Doni (c. 1506; sanguine on paper; Florence, Casa Buonarroti) |

|

| Michelangelo, Sibilla Delfica (c. 1508-1510; fresco; Vatican City, Sistine Chapel, vault) |

|

| Michelangelo, Libyan Sib yl (c. 1508-1510; fresco; Vatican City, Sistine Chapel, vault) |

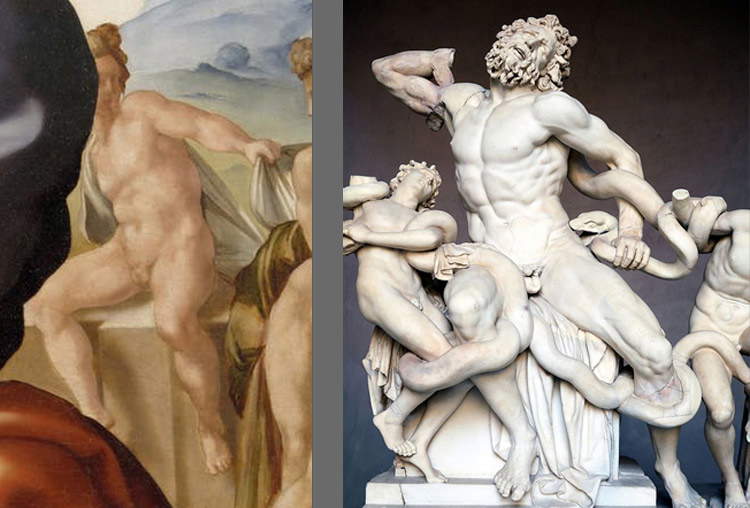

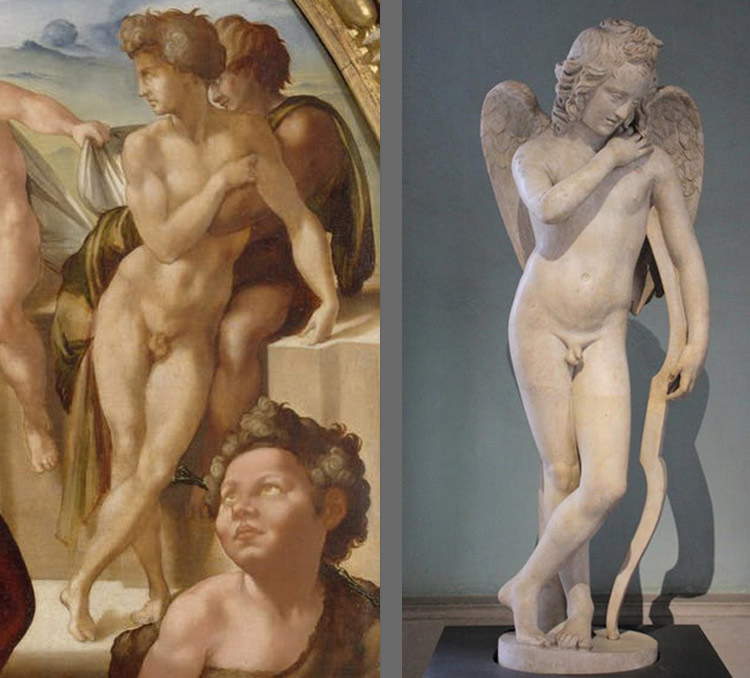

An additional detail was then identified that helps to support the hypothesis that the Tondo Doni is dated after 1506. Behind the Holy Family (the protagonists of the painting are in fact the Virgin, St. Joseph and the Child Jesus) appear classical nudes (the meaning of which we will return to in a moment): one of these, the one we see immediately beside the shoulder of St. Joseph, would seem to quote in an almost literal way the very famous sculptural group of the Laocoon, the extraordinary Roman marble copy of a Hellenistic original that is now in the Vatican Museums and was found in a field in Rome in January 1506. Michelangelo, who had recently established relations with Pope Julius II, was among those who witnessed the excavation of the Laocoon: it is therefore entirely fair to imagine that the statue had provided him with an important cue for his painting. However, this is not the only classical quotation that characterizes the Tondo Doni. The figure that appears near the right arm of the Madonna is shown in a pose quite similar to that of theApollo del Belvedere, the classical sculpture, also now in the Vatican Museums, discovered in the late fifteenth century on land belonging to the della Rovere family (the work was part of the personal collection of Pope Julius II, born Giuliano della Rovere, and following his election to the papal throne was transferred to the Vatican Palace). The first of the classical nudes, on the other hand, would seem to be taken almost slavishly from theseated Apollo now in the Uffizi, a Roman marble from the 1st century AD that replicates a Hellenistic original from the 3rd or 2nd century BC. The last one on the right, the one with crossed legs, recalls the Cupidwith bow today on display in the Uffizi Tribune. And again: in 1985, again Antonio Natali speculated that the head of the Virgin was to be related to a marble head also from the Hellenistic age. It is a triton emerging from the water, which, however, in Renaissance times was interpreted as a dying Alexander the Great, and with that identification the sculpture is known today. The work, in the mid-16th century, was part of the collection of Cardinal Pio da Carpi, and would not enter the Medici collections until 1574.

The relationship between the so-called “Dying Alexander the Great” and the Madonna of the Tondo Doni is now made explicit by the set-up of the new room 41 of the Uffizi’s Corridoio di Ponente, which opened in 2018 with works by Michelangelo, Raphael, and Fra’ Bartolomeo: the Hellenistic marble and the Tondo Doni have been arranged side by side to make these possible relationships of dependence evident (on the opposite side of the room, however, are the portraits of the Doni couple, executed by Raphael around 1506). In contrast, the previous set-up, designed by Antonio Natali and opened in 2012, read the Tondo Doni ’s evident relationship with classical statuary in another way. At the center of the room had been placed a sculpture depicting anAriadne, and also known as Cleopatra again because of a misinterpretation from the Renaissance period: the so-called Cleopatra is mentioned by Giorgio Vasari in the proem of the third part of his Lives, in the 1568 Giuntina edition. The topic is the degree of evolution that, according to the celebrated art historian and artist from Arezzo, the arts had reached before such stars as Leonardo da Vinci, Giorgione, Correggio, Bramante, Raphael, and, of course, Michelangelo rose. While acknowledging to their predecessors (such as Verrocchio and Pollaiolo) the ability to execute “more studied figures, and that there appeared within greater design, with that imitation more similar and more to the point to natural things,” Vasari stressed the lack of a “fine et una estrema perfezzione ne’ piedi, mani, capegli, beards,” and of those “minutiae of the ends” that would have given “a resolute galliance in their works and would have resulted in the gracefulness et una pulitezza e somma grazia, che non ebbono, ancora che vi sia lo stento della diligenzia, che son quelli che darenno gli stremi dell’arte nelle belle figure, o di rilievo o dipinte.” That finesse and assurance that, according to Vasari, the generation before Michelangelo’s could not have, were instead obtained by the younger artists who were able to “see certain antiquities being hollowed out of the ground, mentioned by Pliny of the most famous: the Lacoonte, lErcole et il Torso grosso di Bel Vedere, so the Venus, the Cleopatra, the Apollo et infine altre: le quali nella loro dolcezza e nelle loro asprezze con termini carnosi e cavati dalle maggior bellezze del vivo, con certi atti che non in tutto si storsono, ma si vanno in certe parti movendo e si mostrano con una graziosissima grazia.” These discoveries enabled artists to overcome “a certain dry and crude and sharp manner” that in Vasari’s opinion had characterized the production of artists such as Botticelli, Piero della Francesca, Giovanni Bellini, Andrea Mantegna, and Luca Signorelli. For Vasari, the discovery of the antique was at the origin of the so-called third manner, the “modern” manner, in which the highest degree of minuteness and imitation of nature would be achieved.

For Michelangelo, however, the matter becomes even more complex, according to Vasari. Buonarroti is in fact, in his opinion, the artist who held the supremacy in all three main arts (painting, sculpture and architecture). “Costui,” we read again in the proem, “surpasses and conquers not only all those, who have almost already conquered nature, but those very famous ancients, who so praiseworthy beyond all doubt surpassed it: et unico si trionfa di quegli, di questi e di lei, non immaginandosi appena quella cosa alcuna così strana e tanto difficile, chegli con la virtù del divinissimo ingegno suo, mediante lindustria, il disegno, larte, il giudizio e la grazia, di gran lunga non la trapassi.” Comparison with the ancients was one of the main themes of artistic debate in the mid-sixteenth century: for Vasari, Michelangelo had been able to surpass in confidence, grace and perfection all the statues of antiquity. Statues that Michelangelo knew how to look to in order to produce works capable not only of rivaling the ancient (consider that, at the time, the perfection of classical statuary was a model to aspire to), but also of proving to be better than what the Greeks and Romans had been able to create. A judgment that was later made even by Benedetto Varchi (Montevarchi, 1503 - Florence, 1565), who, in his funeral oration for Michelangelo, recited by the Tuscan humanist himself, went so far as to affirm that the artistic value of the David was higher than all the ancient statues of Rome put together.

Also deserving of further study is the group of the Holy Family in the foreground, which vertically occupies the entire composition (Luciano Berti wrote that “that cranial box” of St. Joseph “with little could bump on the upper edge of the frame, and it would resound”): their daring contortions (the Virgin, seated on her knees in the foreground according to an iconography reminiscent of the Madonnas of Humility in medieval painting, with raised arms holds the infant Jesus, in turn with his body in torsion, as he receives it from St. Joseph, who is instead kneeling behind: a layout that has no precedent in the history of antecedent art) led Roberto Longhi to call it the “divine family of jugglers.” The group of the three protagonists develops in a pyramidal sense, in ways that do not appear so distant from those that Leonardo da Vinci sometimes experimented with and that characterized several of his compositions, while the spiral movement triggered by their twists also springs from Michelangelo’s admiration for Hellenistic art. The Tondo Doni, moreover, further develops a path on this format that Michelangelo had for some years started in sculpture, producing marble masterpieces such as the Tondo Pitti or the Tondo Taddei: in the 1980s, the scholar Roberto Salvini, who was also director of the Uffizi, noted how the three “tondi” were the result of a comparison with the art of Leonardo da Vinci that led him to a greater awareness of the problem of inserting figures in space, he who, on the other hand, wrote Salvini, had previously “rejected the perspective conception of space,” arriving instead at an “exaltation of the solitude of human images, dramatically projected in a foreground without a background.” Comparison with Leonardo modifies these preferences, as Berti would later also confirm by pointing out that the Tondo Doni “conformed to Leonardo’s axioms with an evidence that needs no comment.” The Vinccian had written, in part three of his Treatise on Painting, that distant figures should be “merely hinted at and not finished,” otherwise the risk would have been to produce an effect not in line with what the eye sees in reality: and even though Michelangelo, contrary to Leonardo’s prescriptions, executed the nudes in the background with a certain definiteness, he did not fail to draw on the lesson of Leonardo’s aerial perspective by slightly blurring the contours of the figures in the middle distance (and even more so those of the mountains in the background), and likewise he adhered to the so-called color perspective with the result that the classical nudes present a coloring “more synthetic and chiaroscuro by masses rather than by plastic turning, with the contrast also occurring in many sculptures between ’finished’ front parts and more distant ’unfinished’ parts.”

Michelangelo’s experimentalism also fully invests the colors of the three protagonists: the colors of their robes are icy and iridescent (the faded red of the Virgin’s robe, the dull yellow of St. Joseph’s tunic, the almost glacial blue of the Madonna’s mantle) and anticipate the chromatic figures that will be characteristic of Mannerist painting. The great art historian Cesare Brandi has offered with icastic precision an explanation of Michelangelo’s choice of these tones: "it is clear that Michelangelo intended to neutralize color in order to concentrate the force of spatial expression, with a plastic as sharp as a sculpture is sharp. And it would suffice to compare the folds of the robes with those in the Pietà of St. Peter’s, just before, to see the close kinship: equal plastic intensity, equal independence from color. In the Pietà the white of the marble has the same value as the blues, reds, and yellows of the Tondo Doni. That is, these colors have no value in themselves, but only subordinate to the form on which they emerge."

|

| Left: The first nude from the Tondo Doni. Right: Roman art, Seated Apollo (1st century AD; marble; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Left: The second nude from the Doni Tondo. Right: Roman art, Apollo of the Belvedere (c. 350 BC; white marble, height 224 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums) |

|

| Left: The third nude from the Doni Tondo. Right: Roman art, Laocoon (1st century BC. - 1st century AD; white marble, height 242 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums) |

|

| Left: The fourth nude of the Doni Tondo. Right: Roman art, Cupid with bow (mid 2nd century AD; marble, height 130 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Alexander dying (first century B.C.; marble; Florence, Uffizi Gallery). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Uffizi, installation of the Tondo Doni room with the Cleopatra (2012 - 2018). |

|

| Uffizi, new installation of Room 41 (2018 - ). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

To introduce the significance of the Tondo Doni, it is first worth clarifying that the idea of inserting some classical nudes behind the Holy Family is not original: Michelangelo’s idea owes some debt to the Madonna of Humility (or Medici Madonna) by Luca Signorelli (Cortona, c. 1450 - 1523), also preserved in the Uffizi, where the two protagonists, the Madonna and Child, appear in the foreground while behind them four little naked shepherds can be seen against the background of an open landscape (Michelangelo probably became acquainted with the work, made in the Medici context, during his frequentation of the Garden of San Marco). The most frequent reading that has been given for the shepherds who appear behind Jesus and Mary in Signorelli’s panel wants their presence to be a symbol of humanity ante legem, that is, before God dictated the tablets of the Law to Moses (an interpretation that would also seem to be supported by the presence of the ruins behind them, which would allude to the temples of the pagan gods), while Jesus, in contrast, would become a symbol of the age of grace. Based on this assumption, similar readings have also been provided for the Tondo Doni: the nudes would represent humanity ante legem, Mary and Joseph humanity sub lege (i.e., after the Law of Moses), and Baby Jesus the world sub gratia, i.e., from the revelation of Christ onward, with St. John, peeking out beside the protagonists, to represent the connection between the pagan world and the Christian world (this at least according to the famous reading of Charles de Tolnay for whom, however, it is necessary to recall for the sake of completeness, Signorelli’s shepherds would not have been ancient characters, but rather shepherds from the New Testament: a hypothesis, however, discarded by many other critics). According to others, Signorelli’s shepherds could also be those who in Virgil’s fourth Egloga announce the coming of a puer, or child, who will bring a new golden age (Christ, according to medieval exegetes).

Michelangelo’s nudes, however, are different: first of all, there is a fundamental difference, namely, they have no attributes that could identify them as shepherds, and above all, they are completely nude, unlike those that appear in Signorelli’s painting instead. It is therefore evident that their meaning must be slightly different. William Page, in the late nineteenth century, thought they were wingless angels, an interpretation later followed by others even in the late twentieth century. Others, however, made de Tolnay’s theories their own, perhaps adding additional levels of interpretation: Colin Eisler, for example, suggested identifying the nudes as athletes symbolizing virtue. Still others referred to the cultural climate of late 15th-century Florence, seeing in the nudes an allegory of Platonic love. Recently another, very fitting reading has been proposed: the scholar Chiara Franceschini, in particular, has focused her attention on the figure of the little Saint John, who is not only connected to the sacrament of baptism, thus corroborating the hypothesis that the work might have been made to celebrate the birth of Agnolo Doni and Maddalena Strozzi’s first-born daughter, but in the composition he physically occupies the space that connects the Holy Family and the nudes behind them. In his 2010 essay, Franceschini cites a pair of studies by Frederick Hartt, in which reference was made to a letter from Ugo Procacci, who in turn informed Hartt that he knew of documentary sources that reported how the Doni family, before Maria, had had a number of children, all named Giovanni Battista, and all died shortly after birth. No evidence was found to support this information, but since nearly four years passed between the wedding date and Mary’s birth, this is entirely plausible, since couples of the time tended to give birth to their first child shortly after marriage. An eventuality that would also lead us to assume that these children did not survive long enough to be baptized. And that the Doni strongly wanted a child, as Antonio Natali has also noted, is also evidenced by the fact that on the back of the portraits executed by Raphael (and now visible thanks to the exhibition opened in the summer of 2018) appear depictions of two episodes from the myth of Deucalion and Pyrrha, attributed to the so-called Master of Serumido (in particular, on the back of the portrait of Magdalene appear Deucalion and Pyrrha repopulating the earth after the flood unleashed by Jupiter).

At the time, the early demise of infants was accompanied by concern about the fate of their souls, should they die before being baptized. This fate was the subject of theological debates of the time: the Dominican Antonino Pierozzi (Florence, 1389 - Montughi, 1459), reworking cues from Thomas Aquinas, imagined that the unbaptized were destined for limbo and then resurrected with bodies of thirty-three-year-old men, without, however, experiencing either the pain of Hell or the glory of Paradise. According to other theologians, the unbaptized would be destined, after the Last Judgment, for the earthly world, where they would spend happy times. In Florence, these doctrines also spread thanks to some of Savonarola’s writings, and it is likely, Franceschini points out, that both Michelangelo and the Doni were familiar with them, as they were well circulated in Florence by the friars of the convent of San Marco (after all, we know from Ascanio Condivi, Michelangelo’s first biographer, that the artist was well aware of Savonarola’s sermons, and that he also read some of his writings). The scholar therefore speculates that the nudes could be the unbaptized resurrected, partly because of the fact that beauty and nudity are two characteristics related to the theme of resurrection. Moreover, in contrast to St. John looking toward the Holy Family (turning his back to the figures behind him, moreover, as if to say that they have not been baptized), the nudes are looking at each other (a possible allusion to the fact that they would not have been touched by Christ’s grace). Franceschini therefore suggests that the Uffizi’s celebrated tondo “may allude to a hope of future life for those who died unbaptized.”

Also deserving of some attention is a further interpretation, by Antonio Natali, which refers to New Testament texts, and in particular to St. Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, in which the saint addresses those who were once pagans and, following conversion, have embraced Jesus Christ, pointing out that “you are no longer strangers or guests, but are fellow citizens with the saints and family members of God, built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, and having Jesus Christ himself as your cornerstone. In him every building grows up well ordered to be a holy temple of the Lord; in him also you together with others are built up to become the dwelling place of God through the Spirit.” According to Natali, the Tondo Doni is probably an illustration of this passage: the nudity of the young men in the background represents liberation from sin, and the wall they lean against would be a symbol of the “holy temple” that each of them contributes to forming and that alludes to the Church of Christ. The whole would connect to the event of Mary’s birth Doni in that it is through baptism (which is one of the themes of St. Paul’s letter) that one enters the Christian community.

|

| Luca Signorelli, Madonna of Humility (c. 1490; tempera on panel, 170 x 117.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Raphael, Portrait of Agnolo Doni (c. 1506; oil on panel, 65 x 45 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Raphael, Portrait of Maddalena Strozzi (c. 1506; oil on panel, 63 x 45 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Master of Serumido (attributed), The Flood of the Gods, recto of portrait of Agnolo Doni |

|

| Master of Serumido (attributed), Deucalion and Pyrrha repopulate the earth, recto of portrait of Maddalena Strozzi |

|

| Raphael, Borghese Deposition (1507; oil on panel, 174.5 x 178.5; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

As for the history of the Tondo Doni, we know that towards the end of the 16th century Agnolo Doni’s heirs had experienced a decline in their fortunes, and it was perhaps due to such circumstances that the work was sold, although we do not know for sure what the reasons were. Thus, on June 3, 1595, from the house of Giovanni Battistaa Doni (Agnolo’s son) the work was taken from the home of Giovanni Battistaa Doni (Agnolo’s son) to be taken to the residence of its purchaser, the Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinando I de’ Medici, who hung it in his bedroom in the Pitti Palace (a note of payment reads, “addì 3 di giugno d. quattro [...] to Piero di Bernardo with two fellow grand ducal fachini et sono for having brought from the house of Doni in the Corso de’ Tintori to Pitti in H.H.’s room a painting of a large virgin by Michelagnolo Buonaruoti”). During the seventeenth century, the painting was disassembled from its frame by Francesco del Tasso to be mounted on a rectangular frame more in keeping with the taste of the time.It was not until 1902 that the Tondo Doni was reunited with its original frame, which was in storage at the Uffizi Gallery. The rediscovery for the frame, moreover, dispelled all doubts as to the work’s private destination, and rekindled critical interest in the Tondo Doni.

And although Michelangelo’s celebrated panel knew some periods of critical misfortune, there is no longer any doubt, at least since the early twentieth century, that it represents, on the contrary, one of the highest texts in the entire history of art: Cesare Brandi, even, wrote that “there is perhaps no painting in the world higher and more pregnant than Michelangiolo’s Tondo Doni.” A very modern painting, it is the basis of painting throughout the sixteenth century, and was a source of inspiration for even the greatest. Just think of one of the pinnacles of Raphael’s production, the Borghese Deposition, central compartment of the dismembered Pala Baglioni. And try to imagine where the position of the third of the pious women comes from, the one kneeling on the right, holding the body of the Virgin whose strength fails at the sight of her son being dragged toward the tomb.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.