Two “skillfully complementary” works: this is how scholar Cristina Acidini, among the foremost experts on the art of Michelangelo Buonarroti (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564), defines, in the catalog of the exhibition Michelangelo divino artista (Genoa, Palazzo Ducale, from Oct. 8, 2020 to Jan. 24, 2021, curated by Cristina Acidini and Alessandro Cecchi) the artist’s two earliest known masterpieces, namely the Madonna della Scala and the Battle of the Centaurs, both of which are preserved in Florence, at Casa Buonarroti (and the first of the two exhibited precisely in Genoa for the exhibition). They are both works that date from the period when a Michelangelo, just 15 years old, became linked to Lorenzo the Magnificent (Florence, 1449 - Careggi, 1492), after meeting a fellow artist, then a boy not much older than himself, Francesco Granacci (Bagno a Ripoli, 1469 - Florence, 1543), destined to become one of his most faithful collaborators in the future (with also an interesting activity as an independent artist): it was Granacci himself, Cristina Acidini recalls, who convinced Michelangelo’s father, Ludovico, to indulge the young man’s artistic talent (his parent, who was a civil servant by profession, and when Michelangelo was born held the position of podestà of Caprese, in fact wanted to steer him toward a career in public office, at the time considered more socially prestigious) and, around the same time, to introduce him to the de facto lord of Florence.

At the time, the Magnifico posed himself to all intents and purposes as a patron of young talents in the arts: in the so-called Giardino di San Marco, that is, a courtyard attached to the Casino Mediceo and close to the church and convent of San Marco (hence the name by which this space is known to scholars and enthusiasts of Renaissance art history), where some ancient statues from the Medici’s rich collection were located, Lorenzo, since the 1980s, had provided a home for young artists by allowing them to practice their artistic practice and drawing by copying ancient sculptures: the Garden was thus a place where, thanks to a clever intuition of the Magnifico, ancient and modern met to train young artists. Without, of course, any programmatic intentions, as one might suspect from reading the pages of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives, in which the Arezzo historiographer writes that Lorenzo supremely desired “to create a school of excellent painters and sculptors.” The Garden was actually not a school, as more recent studies have shown, but more simply a site, Acidini writes, “set up in such a way as to allow the study of archaeological pieces from the Medici collections, the creation of ephemeral apparatus, and the working of marble and building materials.” It is here that we have to imagine the young Michelangelo taking his first steps as a sculptor, conversing, comparing and certainly even quarreling with other young men like himself, and listening to the suggestions of his first master, that Bertoldo di Giovanni (Florence, c. 1440 - Poggio a Caiano, 1491) who was at the time one of Donatello ’s rare surviving pupils and collaborators, and who was mentoring the young men in the Garden of San Marco. And we can imagine the young Michelangelo as he even talks with the Magnifico himself who, says Ascanio Condivi, Michelangelo’s first biographer, had a strong interest in the boy.

An interest that, moreover, was to have important consequences for the rest of his career, since Michelangelo was also sometimes invited to the Medici palace, and here he got to know the Magnifico’s sons, including his contemporary Giovanni de’ Medici (Florence, 1475 - Rome, 1521), later to become Pope Leo X in 1513, and his nephew, the younger Giulio (Florence, 1478 - Rome, 1534), who was also destined to ascend to the papal throne, in 1523, with the name of Clement VII. A famous anecdote, recounted by all ancient biographers (Condivi, Vasari, Benedetto Varchi) tells of a very young Michelangelo who saw, in the Medici collections, the head of an old faun, which was missing its mouth: not only did he copy it perfectly, but his inventiveness led him to add what the ancient statue lacked. Lorenzo the Magnificent saw Michelangelo’s work, and to tease him he told him that old men, however, do not have all their teeth: Michelangelo, sitting there, reshaped the mouth to remove some teeth and make it look more believable. The episode greatly amused the Magnifico and was taken as an example by biographers as revealing the artist’s talent and genius. The one at the Garden of San Marco was an intense but short-lived experience, since the Magnifico died on April 8, 1492, and his son Piero, although he had an interest in the arts and granted his protection to Michelangelo, did not prove to have the same caliber and talent as his father. The death of the Magnifico thus sanctioned the end of the Garden of San Marco, and Michelangelo’s return to his father’s house.

|

| Ottavio Vannini, Michelangelo Shows Lorenzo the Magnificent the Head of the Faun (1638-1642; fresco; Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Sala di San Giovanni) |

|

| Michelangelo’s early works at Casa Buonarroti |

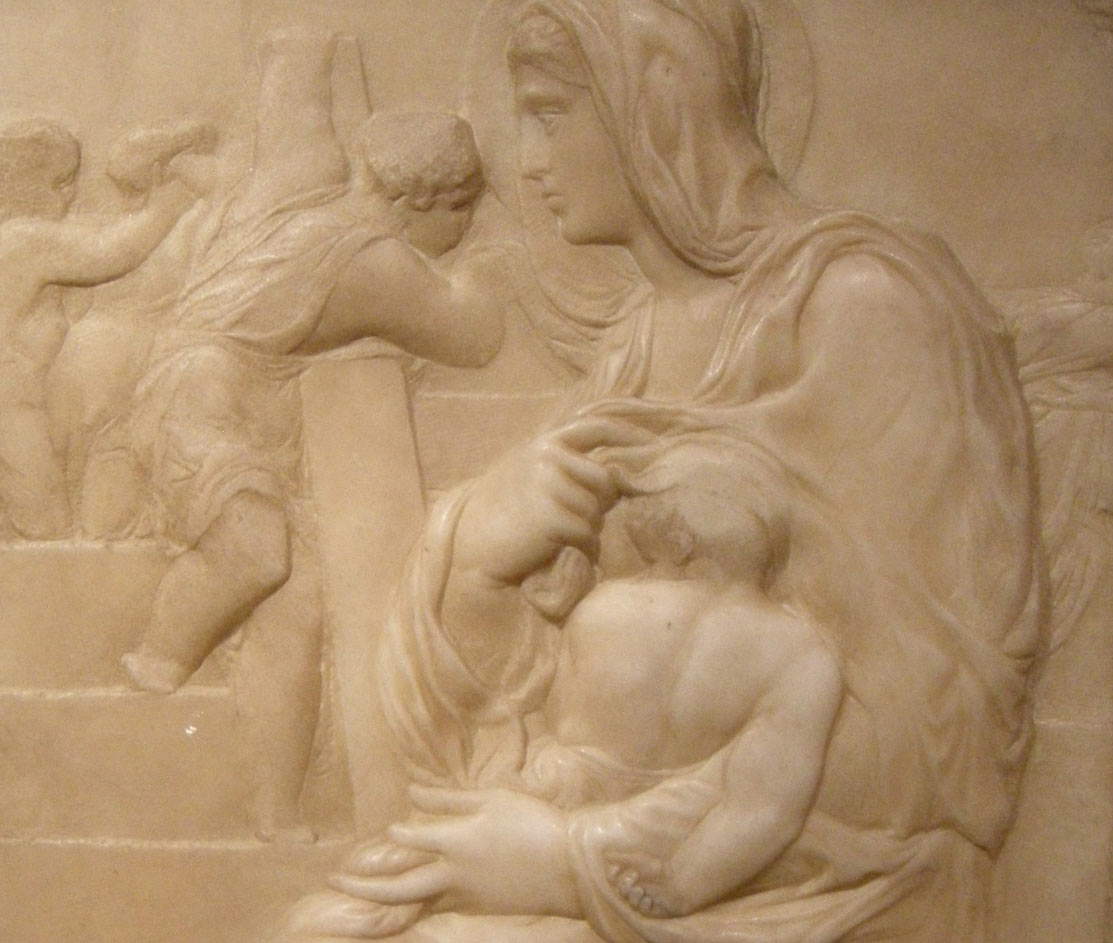

It is in this context that the creation of the Madonna and the Battle of the Centaurs takes place. The former, more acerbic than the latter, is to be considered chronologically earlier. Vasari himself speaks of this original relief: the author of the Lives reports that Leonardo Buonarroti, son of Michelangelo’s younger brother Buonarroto, had donated to Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici (who, Vasari writes, “holds it for a most singular thing, there being by his own hand no other bas-relief than this one of sculpture”), a “Nostra Donna di basso rilievo di mano di Michelagnolo di marmo alta poco più d’un braccio, nella quale sendo giovanetto in questo tempo medesimo, volendo contrafare la maniera di Donatello si portò così bene che par parse di man sua, tranne che vi si vede più grazia e più disegno.” In his description, Vasari had noted the most obvious element of this early Michelangelo test, namely the attempt to use stiacciato, the technique through which Donatello, in his reliefs, suggested to the observer a sense of depth, making the figures closer to the subject more projecting and, conversely, the figures that, in the fiction of sculpture, were supposed to be farther away from the background less detached. This is what Michelangelo also tried to do, still with a somewhat uncertain manner due to inexperience (see, for example, the arm holding the Child that seems almost detached from the body of the Virgin, or the putto that has a strong overhang of the shoulder, which, on the other hand, is much less in the legs) but nevertheless proposing his own interpretation of Donatello’s technique, in a more solemn key, with the figures prevailing over the space, so much so that the planes do not appear scaled in depth, but it is only the figures that suggest distance (whereas in Donatello’s reliefs there was no lack of perspective-set space). “Michelangelo’s relationship with Donatello,” has written art historian Pina Ragionieri, longtime president of Casa Buonarroti, “appears, already in this work so youthful, personal, intense, and undoubtedly rupturing: a fascinated revisitation, but already polemical and dismissive.” But that’s not all: the closeness to Donatello is also shown by the similarities with the Madonna that the latter made in the Lamentation scene in one of the reliefs decorating the Pulpit of the Passion in San Lorenzo in Florence, where we see a Virgin in the same pose as the Madonna of the Staircase, with even her hand resting in the same way.

Michelangelo’s Madonna is seated on a large, stepped staircase (hence the name by which the relief is universally known) and holds the Child in her hands (with her left arm she supports him, while with her right she holds her veil over the head of the little one), while on the staircase two figures of putti appear, deep down, in an attitude that has not been well clarified: they appear to be dancing. The figure of the Madonna occupies the entire composition vertically, and appears seated as if on a throne.Michelangelo was only fifteen years old but was already capable of sculpting figures of monumental impact, such as those he would execute even in the more mature stages of his career, when he would become a successful artist. And again, there are features from which it is possible to guess how innovative the young Michelangelo’s flair is: in particular, the idea of depicting the Madonna in profile, that of catching the Child turned from the back, and the very insertion of the two children playing on the staircase, a detail so original that its meaning has not yet been well framed.

The most reasonable explanation of the work might be the one that, meanwhile, sees in the ladder the symbol of the union between heaven and earth and consequently between men and the divine sphere. It is in this sense rather easy to recall chapter 28 of the book of Genesis, where Jacob’s dream is recounted, “He had a dream: a ladder rested on the earth, while its top reached to heaven; and behold, the angels of God were ascending and descending on it.” This could have been an image that Michelangelo had in mind, not least because it was very common in Renaissance and medieval iconography, and in this sense the Virgin could serve a further function as a conduit between men and God: all the more so because according to some scholars (although the argument does not seem the strongest) the five steps of the staircase could allude to the five letters that make up Mary’s name. But it is also possible to read the work within the framework of Michelangelo’s juxtaposition with Ficinian Neoplatonism, and in this sense the staircase could be seen as the symbol of the soul rising toward contemplation, one of the themes of Neoplatonic philosophy. The work would thus lie somewhere between Ficinian humanism and medieval-derived mysticism, expressing a tension that well embodies the spirit of the nascent Savonarolian age.

It is in these terms that the Madonna della Scala has been read by a scholar such as Maria Calì, according to whom Michelangelo’s work “still seems humanistic, but it already denies Humanism; it represents a rottur with the past, both from a formal, ideological and cultural point of view, but, looking to the future, it turns to a past that is even more distant in time, that of the medieval age.” For Calì, Michelangelo’s Madonna, “grand and distant as a Pheidian sculpture, seems to preserve the integrity and purity of the classical form,” but at the same time “a restlessness snakes along the body of the Virgin, through the vibrant drapery, which envelops the whole person in wide spirals, falling back in thicker folds along the wrists, allowing glimpses of the large, full-bodied hands.” Even more indicative in this sense is the presence of the infant Jesus, “engaged in a difficult, almost unbelievable twist, which interrupts the seemingly fluid drapery of the figure of the Madonna.” And so the Madonna of the Staircase becomes a masterpiece that “already presents in full the formal and ideological problematics that Michelangelo was to develop in later years,” a poetics where the humanistic world coexists with “motifs of obscure meaning that are exhumed from the ancient medieval tradition,” in this case Jacob’s ladder.

|

| Michelangelo, Madonna della Scala (c. 1490; marble, 56.7 x 40.1 cm; Florence, Casa Buonarroti, inv. 190) |

|

| Donatello, Lamentation, detail, from the Pulpit of the Passion (post 1460; bronze, 137 x 280 cm; Florence, San Lorenzo) |

|

| Michelangelo, Madonna della Scala, detail |

|

| Michelangelo, Madonna della Scala, detail |

The Battle of the Centaurs, Michelangelo’s other early masterpiece, is a little later, and is placed by critics in a period that always coincides with that of his frequentation of the Garden of San Marco. It is first mentioned when the artist was still alive and in full activity, to be precise in a letter dated March 5, 1527 and sent by Giovanni Borromeo, the Gonzaga’s agent in Mantua, to Marquis Federico II Gonzaga, who was looking for a work by Michelangelo at the time. In the missive, there is mention of a “certain painting of naked figures, fighting, in marble, which hasa principiato ad istantia dun gran signore, but is not finished. It is braccia uno e mezzo a ogni mane, et così a vedere è cosa bellissima, e vi sono più di 25 teste e 20 corpi varii, et varie attitudine fanno.” However, the Battle is mentioned by Michelangelo’s main sixteenth-century biographers, although Condivi and Vasari disagree on the subject, since for the Marche native it is a “rape of Deianira and the tussle of the Centaurs.” while for the Aretine the relief depicts “the battle of Hercules with the centaurs,” which, Vasari adds in praising the sculpture, “was so beautiful that sometimes for those who now consider it it does not seem to be the hand of a young man, but of a valuable master and consummate in his studies and practical in that art.” Vasari, moreover, recalled that, exactly like the Madonna della Scala, the work at the time of the writing of the Lives was in the house of Leonardo Buonarroti, and it is interesting to note that it has never moved from the family home since then, as it is still in the collection of Casa Buonarroti in Florence. As for the subject, other scholars (e.g., Angelo Tartuferi and Fabrizio Mancinelli) identify in it a brawl between centaurs and lapiths: this is the mythological episode that, Ovid’s Metamorphoses recounts, would have occurred during the wedding festivities between Hippodamia and Pyritoo, the latter king of the Lapiths (the centaurs, invited to the wedding, after getting drunk allegedly tried to kidnap the bride, thus triggering a brawl with the Lapiths, who would eventually prevail).

Whatever the subject, however, it is clear that Michelangelo was already familiar with learned themes drawn from classicism, liable to allegorical readings in a neo-Platonic key (for example, a possible struggle between man’s feral nature and his spiritual drives, another theme dear to Ficinian philosophy): in this case, the subject of the relief may have been suggested by a poet of the Laurentian circle, Poliziano (Angelo Ambrogini; Montepulciano, 1454 - Florence, 1494), at least according to Condivi’s recollection. The subject is also difficult to interpret due to the fact that the artist is not so much interested in the description of the episode itself as in its restitution, the depiction of the bodies in battle, and the anatomical rendering of the characters engaged in the brawl. And in spite of his very young age, Michelangelo is already able to propose an original way of treating space: in fact, the figures are arranged on multiple planes and do not blur in a rigid and orderly way, but almost overlap one another, in a way that is nonetheless very credible and verisimilar. The modernity of the work becomes even more evident when one compares Michelangelo’s work with the Battle of Bertoldo di Giovanni preserved in the Bargello Museum in Florence, a relief from which Michelangelo probably drew some cues, given also his closeness to the older master. It is clear from the comparison how somewhat distant Michelangelo’s construction of space is from Bertoldo’s, since the typically 15th-century perspective layout is already abandoned by Michelangelo, and the same is true for the minute rendering of details. On the contrary, Michelangelo abolishes the background and frame, and is all concerned with the modeling of the contenders’ bodies, communicating through them the depth of the scene, and demonstrating that he had already achieved his own independence in his treatment of the male nude.

It should be specified, however, that this was a “begun” but “unfinished” work, as Borromeo wrote in his letter to the Marquis of Mantua: in all the figures the marks of the artist’s chisel are still evident (and are therefore unfinished), there are pieces of marble still attached to the background behind the bodies of the figures, and above all there is a band at the top that is still all to be hewn: it has therefore been assumed that Michelangelo had left this work unfinished at the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent, for whom it was probably intended, as one might surmise from reading Borromeo’s letter and thus identifying the Magnificent as the “great lord” mentioned. However, even here, as in the Madonna della Scala, we recognize some of the motifs that will be characteristic of the mature Michelangelo: the strong dynamism, the attention to the male nude, the unfinished, the absence of the background. Elements that already foreshadow the tensions of the mature Renaissance and the arrival of Mannerist poetics. And motifs that would return: it has often been pointed out that the central figure of the Battle of the Centaurs anticipates the powerful Christ Judge of the Last Judgment that decorates the back wall of the Sistine Chapel. And whatever the young Michelangelo’s references were (Bertoldo di Giovanni has been mentioned, some have proposed locating the artist’s inspiration in Roman sarcophagi, others in the slabs that decorated Giovanni Pisano’s pulpits), the sculptor was able to surpass them to promote, even at the age of fifteen, a personal and very modern manner.

|

| Michelangelo, Battle of the Centaurs (c. 1490-1492; marble, 80.5 x 88 cm; Florence, Casa Buonarroti, inv. 194) |

|

| Bertoldo di Giovanni, Battle (c. 1480-1485; bronze, 45 x 99 cm; Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello) |

|

| Michelangelo, Battle of the Centaurs, detail |

|

| Michelangelo, Battle of the Centaurs, detail |

|

| Michelangelo, Battle of the Centaurs, detail |

And so it is that from the masterpieces of the adolescent Michelangelo already emerges the figure of a solid, original artist, confident of his means almost to the point of effrontery, already capable of conveying, through marble, a sensibility uncommon for a boy of only fifteen, devoid of reverential fears and, indeed, already able to reread tradition in order to surpass it without making too much of a fuss. A personality that could not fail to amaze his contemporaries. Premises from which it was already easy to guess what would be the path of one of the greatest artists in the history of art.

And those that emerge from the youthful works, Acidini wrote again, are therefore "elements of affirmative and mature originality: mysteriously innovative hints in the Madonna (the trim in profile, the Child from behind, the putti for the stairs), and then, auroral inclinations to complexity and self-imposed difficulty, which are expressed in the primordial mixture of human and equine limbs carved out of the meager thickness of the marble slab of the Battle. Amidst twisting, stretching, straining and grasping each other, the protagonists assume improbable and painful postures that enhance the bodily structure of each, multiplying opposites: rotating busts, hunched backs, laced arms, gestures of violence and overpowering, but also painful folds. Like an embryonic archive of volume and surface workings, the relief seems to contain every future choice Michelangelo made, and not infrequently its opposite: hollow and protruding, smooth and rough, finished and unfinished, in a skillful orchestration that will give rise to inexhaustible variations."

Essential Bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.