“Michelangelo [...] from his modest castle where that great man was born, my thoughts turn to Vespignano, to Vinci, to Certaldo where Giotto, Leonardo, Boccaccio were born, and to so many other Italian lands from whence other supreme men came forth to illustrate their country with egregious works, to increase its culture, and to broaden its fame among civilized peoples. [...] Wonderfully restored today the free orders with forms better suited to our times, ignited the people by the noble eagerness to celebrate the birthdays of the illustrious departed, for which no less than the most populous cities, rose in fame the most remote and obscure villages.”cAlready in this excerpt from an oration, delivered by Mayor Petrucci of Caprese, today Caprese Michelangelo, on the eve of 1875, when the celebrations of the most illustrious son of these lands, Michelangelo Buonarroti, were held in Italy, the strategic importance, be it symbolic, political or economic, for which many villages have so intensely supported and wanted to enhance their noble birthplaces, is highlighted. In Caprese, this operation has taken on almost the boundaries of a battle, admittedly good-natured and fought with documents, but no less fierce.

Indeed, although Michelangelo was an artist revered and hailed without interruption by his contemporaries to this day, and we have an extraordinary amount of information about him, probably with few equals compared to the artists of his time (so much so that we even have a list of his groceries), his place of birth is still debated today. Fueling this controversy are the parche sources handed down by Michelangelo’s major biographers, Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi. The Aretine, in the life of Sansovino, wrote that both sculptors were born in Via Santa Maria in Florence, except that he contradicted himself in the life of Michelangelo himself and reported the indication, “Nacque dunque un figliuolo sotto fatale et felice stella nel Casentino” by Ludovico who was “Potestà in quell’anno del Castello di Chiusi e Caprese, vicino al Sasso della Verna.” Condivi himself, in fact, also reported the same information.

The

The

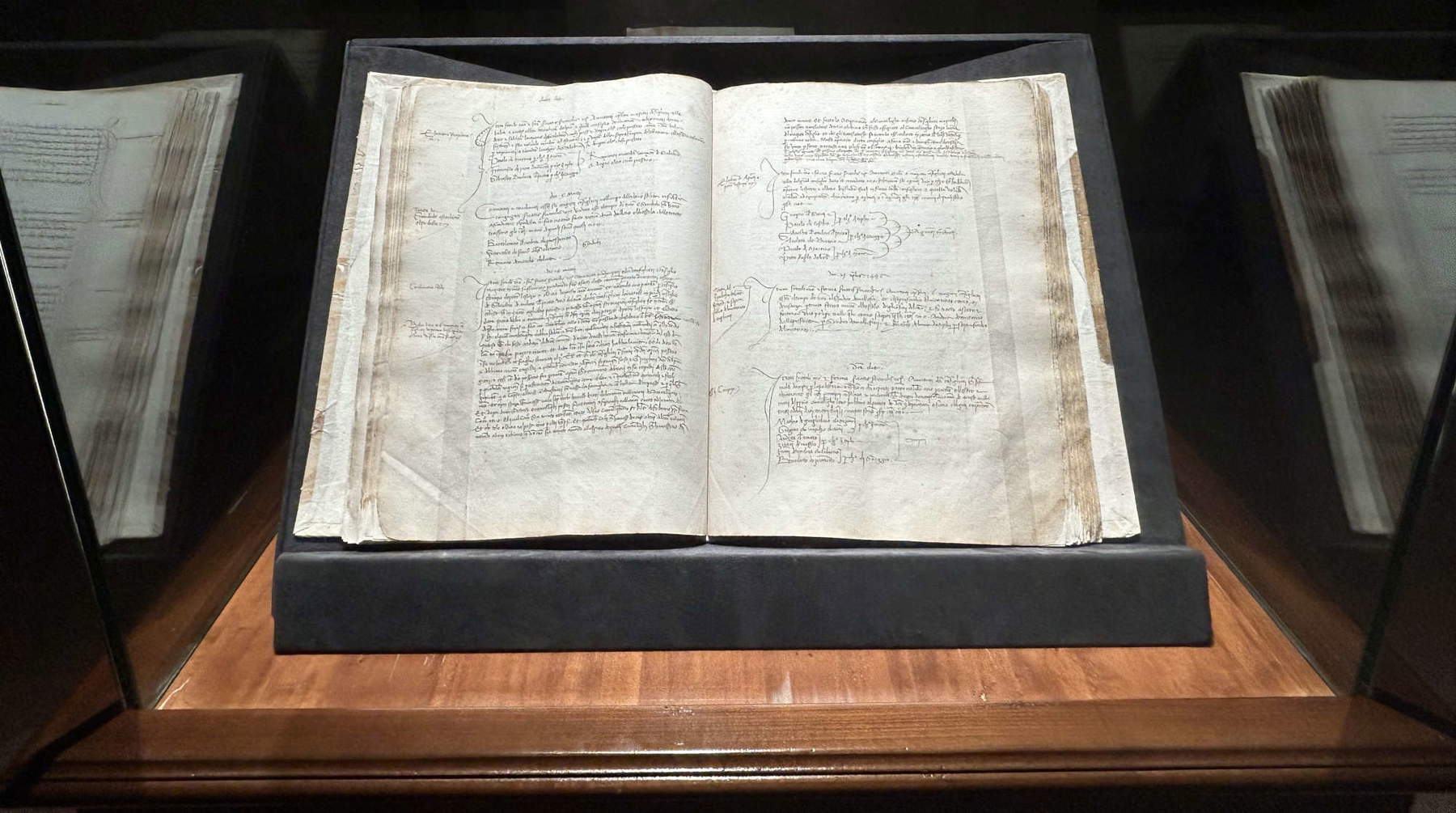

Michelangelo’s birthplace has thus long been disputed between Chiusi della Verna and Caprese, respectively afferent to the Casentino and Valtiberina territories, and even the document that was found at Casa Buonarroti in the run-up to the important 1875 celebrations of Michelangelo’s fourth centenary did nothing to settle the dispute: “I remember how ogi questo dì 6 marzo 1474 - mi nacque un fanciullo mastio posigli nome Michelagnolo, et nacque in lunedì matina, innanzi dì 4 o 5 ore, et nacquemi essendo io potestà di Caprese, et a Caprese nacque [...] Batezossi addì 8 detto, nella Chiesa di S. to Giovanni di Caprese [...].”

This was a copy of a recollection by Ludovico Buonarroti, the sculptor’s father, from his lost Book of Reminiscences, in which he had recorded the birth of his son precisely in Caprese while he was podestà of the unified Podesteria of Chiusi and Caprese. But the fortunate find occurred with a timeliness judged too suspicious, so much so that it is still disputed today, in a diatribe wrought with documents, research and studies.

Nonetheless, it is now rather taken for granted in the common imagination that Michelangelo’s birthplace is to be traced to Caprese, if only because the small village has been named Caprese Michelangelo since 1913, and because the museum dedicated to the artist’s birthplace is located on its summit.

The Michelangelo Buonarroti Birthplace Museum thus draws its origins from that year of grace that is 1875, three months before the pompous celebrations were held in Florence. On that occasion, during the celebrations held in Caprese, a plaque was placed on the facade of the Palazzo del Podestà, which was later followed by one in the room where the artist was supposedly born. From that moment began the history of the museum, making it in fact one of the first artists’ houses to be musealized in Italy.

Today, the visit to the museum has been enriched and is composed of various collection nuclei that deserve a fair amount of interest, as well as the architecture that shows the sedimentation of several centuries, immersed then in a marvelous landscape, still practically uncorrupted, denoted by an almost metaphysical silence and crisp air. In fact, the museum space is arranged in several structures resting on a fortress overlooking the top of a mound, and inside one has not only an in-depth look at one of the greatest artists in history, but also more generally at Italian sculpture.

The first building one encounters is the sober 14th-century Clusini Palace , once the seat of the Chancellery, now housing instead the bookshop and ticket office, while the upper floors unfold a sculptural collection, consisting of medium- to small-scale works by Italian artists active between the 19th and 20th centuries, which came to the Caprese museum in essentially two ways: Either during the celebrations of the fifth centenary of Michelangelo’s birth in 1975, through donations from artists, competitions and temporary exhibitions, or thanks to the important donation granted by a leading figure in Italian culture, Professor Enrico Guidoni in 2006. The two floors are home to works also with resounding names, such as those of Antonio Canova, Medardo Rosso, and Leonardo Bistolfi, but also to the splendid little bodies outlined by the verist hand of Vincenzo Gemito, the mighty hands of the Creator and Adam shaped by Alfredo Battistni and taken from the well-known fresco of the Sistine Chapel that stand out against the panorama of the Apennines, the silhouettes that smell of Mediterranean archetypes by Emilio Greco and Pericle Fazzini, and much more.

Leaving the building and gaining pace in the courtyard, surrounded by an evocative panorama, one encounters the sculptural aedicule by the Florentine Arnaldo Zocchi, placed here in 1910. The work is a play between sculptural reliefs, the one in the round of the cradle that welcomes a baby Michelangelo intent on aiming behind him the dossal that alternates high and low relief where two of the genius’ most famous future sculptures that were born here, the Moses and the Night, impose themselves austere.

The most significant building is the old Podesta house, clad in stone without plaster, which still has on its facade the arms of the Podestas who resided there. Originally the structure had both a residential and representative function. On the ground floor, a projection introduces the living quarters and history of the Buonarroti family in Caprese, while on the upper floor is a copy of Ludovico Buonarroti’s memorial. Here, he held the role of Podestà from September 1474 until March of the following year; moreover, his father, Leonardo, had also obtained the same role twenty years earlier, but kept his residence in Chiusi. Also preserved is a plaster copy of the marble bas-relief known as the Tondo Taddei, made by Michelangelo around 1504 and 1506 and now housed at the Royal Academy in London. In another adjoining small room, the sculptor, who was given the unusual name Michelangelo, is said to have been born, perhaps because of a vow to the Archangel Michael: on September 29, in fact, it seems that his pregnant mother Francesca had fallen from her horse without, however, endangering the health of the child, “especially preserved from heaven.” The event is also recalled by a monochrome by Furini in the Gallery of Casa Buonarroti. In this room is a sumptuous polyptych made for the church of the Camaldolese monastery of Saints Martin and Bartholomew in Tifi, not far from Caprese, and painted around 1460 by Giuliano Amedei, the same author of the predella of Piero della Francesca’s Madonna della Misericordia, preserved in the Museo Civico in Sansepolcro.

Continuing the visit, one passes through the garden, a terrace overlooking the valley that changes its appearance with the changing seasons: here, in communion with the environment, are a number of works by modern authors, such as Cecco Bonanotte’s polymathic sculpture United Family, with which he won the competition for Michelangelo’s celebrations in 1974. Among the others is the Madonna and Child by Antonio Berti, a sculptor and painter who approached art while engaged as a graphic designer at Richard Ginori, and who took up art thanks to the mediation of critic Ugo Ojetti, who convinced his father to have him enrolled at the Florence Art Institute.

In the Upper Court, reconstructed by incorporating the ruins of an older building, a rich gypsoteca of Michelangelo’s works is arranged instead. These are 19th-century plaster casts made for the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, and arrived in Caprese shortly after the mid-20th century, a collection continually enriched with further donations.

Thanks to the copies, it is possible to confront practically the sculptor’s entire output, but there are also rare examples of dispersed works, such as the San Giovannino formerly attributed to Buonarroti, but possibly to be traced back to a 17th-century work by Domenico Pieratti, once in the collections of the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin and destroyed during World War II. Also in this space is a fine bronze copy of the famous bust dedicated to Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra, and a small room holds other modern works, such as the plaster of Adriano Cecioni ’s irreverent Can that Caca and Paolo Troubetzkoy’s more sober dog, as well as Umberto Boccioni’s plaster, Portrait of Iosif Brodsky, the famous poet who was opposed and accused of parasitism during the communist government in the USSR. And still placed here are other small bronzes, a senile self-portrait by Vincenzo Gemito, and a relief with a Portrait of journalist Matilde Serao, made by the famous Cremonese forger Alceo Dossena. The Museum is then completed with a rich library dedicated to Michelangelo and the Historical Archives of the Municipality of Caprese.

Michelangelo’s birthplace is thus not only an exaltation of the empty walls, embellished by the symbolic value of the noble birthplace, but also allows one to come into direct contact (albeit mediated by copies) with the art of the Tuscan master, as well as with a great number of other modern authors in the history of Italian art, all this, in a landscape that very few other museums in Italy can boast.

The author of this article: Jacopo Suggi

Nato a Livorno nel 1989, dopo gli studi in storia dell'arte prima a Pisa e poi a Bologna ho avuto svariate esperienze in musei e mostre, dall'arte contemporanea alle grandi tele di Fattori, passando per le stampe giapponesi e toccando fossili e minerali, cercando sempre la maniera migliore di comunicare il nostro straordinario patrimonio. Cresciuto giornalisticamente dentro Finestre sull'Arte, nel 2025 ha vinto il Premio Margutta54 come miglior giornalista d'arte under 40 in Italia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.