“Anyway, on this planet there is always a war somewhere, and I wanted to create a universal image that referred to war in general”: these words by the artist Marina Abramovi�?, contained in her autobiography Crossing the Walls, published in 2016 by Bompiani, were uttered in 1997, commenting on one of her most famous performances, Balkan Baroque, a reflection on the war that at the time was tearing Yugoslavia, her homeland. Words that seem as true and relevant as ever in these years when the destruction of our planet is the order of the day: from climate issues to energy problems, from viruses dangerous to human health to global and civil wars that annihilate entire generations of peoples and, therefore, the very future of the earth.

The subject of destruction, especially in its worst facet, that of war, has always been present within the history of art. Not only in terms of the subject of the artwork, but also in terms of the object as such. Around the first half of the eighth century, for example, the Empire of Constantinople sought to bring the territories owned by monasteries back under its control by banning the worship of religious imagery. Thus began a religiously motivated movement known as iconoclasm, which led to the physical destruction of many religious images.

The destruction that a war entails has always been a subject with which a great many artists have grappled. The visual arts have always had an ongoing relationship with conflicts, sometimes promoting them, other times serving to concretize a real opposition to them. The most famous case is surely that of Pablo Picasso and his Guernica (1937): in almost three and a half by eight meters, the artist staged the bombing of the Basque city of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War by Nazi troops in support of General Franco. Lorrore, despair and moral and physical destruction were masterfully interpreted by Picasso in one of his best works, now housed at the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid.

If one wants to dwell only on the European situation, the list of civil wars is quite substantial. Among the bloodiest conflicts that have led to the destruction of entire cities and the death of many of its inhabitants is the one that took place in the Balkans, in Bosnia and Herzegovina between March 1, 1992 and December 14, 1995, and that sinserisce in the broader situation of the Yugoslav wars fought between 1991 and 2001, as a consequence of the dissolution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, when, at the end of the 1980s, communism lost its ideological strength favoring the strengthening of nationalism. At the time it was a very bloody conflict involving three main national groups, namely the Serbs, Croats and Bosnians, and several ethnic groups. The conflict in Bosnia led not only to the deaths of nearly one hundred thousand civilians, but also to the flight of more than two million people, becoming in fact the largest displacement of human beings since the end of World War II. It was a conflict that completely destroyed the moral foundations of the society of the former Yugoslavia: nationalist policies caused over time the dissolution of ethnic integrity and tolerance among the respective populations.

Among the artists who have chronicled the devastation of this war, special mention should be made of Marina Abramovi�?, who is on the Montenegrin side, as she states in her 2016 autobiography, Crossing the Walls, “My heart is big but I am a Montenegrin [ ]. And you don’t hurt the pride of a Montenegrin.” The theme of destruction has accompanied almost her entire performance career: a destruction that is to be understood not only in reference to the subject of her works, but also as their object (i.e., her own body), as well as the change inherent in the artistic genre itself.

Balkan Baroque is undoubtedly the performance that consecrated her in the Olympus of celebrities in the art world, winning her the Golden Lion at the XLVII Venice Art Biennale in 1997. It was a charismatic, raw and heartfelt performance, as she recounts in her biography: "Balkan Baroque, the title of my performance, did not refer to Baroque art, but to the Baroque and the madness of the Balkan mentality: the fact that we are cruel and tender, that we are able to love and hate passionately, and all at once. The truth is that only those who were born there, or have spent much time there, can understand the Balkan mentality. Understanding it from an intellectual point of view is impossible: such turbulent emotions are as uncontrollable as a volcano." A testimony that is both precious and powerful, trying to render to the reader what the Balkan conflict may have meant for those who were born there and took their first steps in their artistic careers. The performance saw Abramovi�? sitting on the floor of the Italian Pavilion on a pile of cow bones, more than two thousand of which were soiled with blood, along with meat and gristle. For four days, seven hours a day, the performer was intent on cleaning the bones, while on two screens behind her were projected, without sound, some images from aninterview she had conducted with her parents: her mother Danica (with whom Abramovi�? had always had a contentious relationship) folded her hands over her heart and covered her eyes; her father, Vojin, held his gun. On another screen scrolled a video in which the performer was “dressed as a typical Slavic scientist goggles, white coat, big leather shoes [ ],” and intent on telling how a rat-catcher exterminates rats (the story is also from aninterview with a Belgrade rat-catcher, made several years earlier for the Delusional action). After telling the story of the rat-catcher, Abramovi�? took off her lab coat to transform herself into a seductive dancer who, wearing a black petticoat and a red handkerchief, danced frantically to the beat of a Serbian folk song.

“In that room without air conditioning, in the humid Venetian summer, the bloody bones rotted and filled with maggots, but I kept rubbing them: the stench was terrible, like that of corpses on the battlefield. Visitors would line in and watch, disgusted by the stench, but mesmerized by the spectacle. As I cleaned the bones, I cried and sang Yugoslav folk songs from my childhood.” And again, "Every morning I had to return to soak in a pile of wormy bones. In the basement the heat and the stench were unbearable. But that was my job. To me that was Balkan baroque. Every day, at the end of the performance, I would go back to the apartment I had rented and take a long, long shower, trying to wash off the stench of rotting flesh that had gotten into my pores. Already by the end of the third day it seemed impossible to clean myself." The artist’s own words help to understand what the (perfectly successful) intent of the performance was: Abramovi�? wanted to emphasize that just as it was impossible to wash the blood from dirty hands, in the same way it is impossible to clean one’s soul from the shame of war. One understands, then, that by transcending this very gory image, the work can be a universal symbol of what war destroys both humanly and physically.

A few years later (2001), Marina Abramovi�? made the video The Hero, a performance close to Balkan Baroque in terms of the theme developed by the artist. Filmed in the countryside of southern Spain, The Hero is dedicated to Vojin, the artist’s father and a Yugoslav partisan during World War II. The video is inspired by his parents’ story of when his mother had saved his father’s life. In this work, made just after her father’s death, Abramovi�? sits motionless on a white horse (as her father often did) while holding a white flag fluttering in the wind. At the same time, a female voice sings a Yugoslav national song dating back to the Tito era, now banned throughout the former Yugoslavia. The performance video is deliberately in black and white to emphasize the memory of the past: it is always projected accompanied by a display case containing a bag with photographs and medals. The white flag held by the artist symbolizes her father’s surrender in the face of death, which, as the performer states, is the greatest change with which every human being must contend.

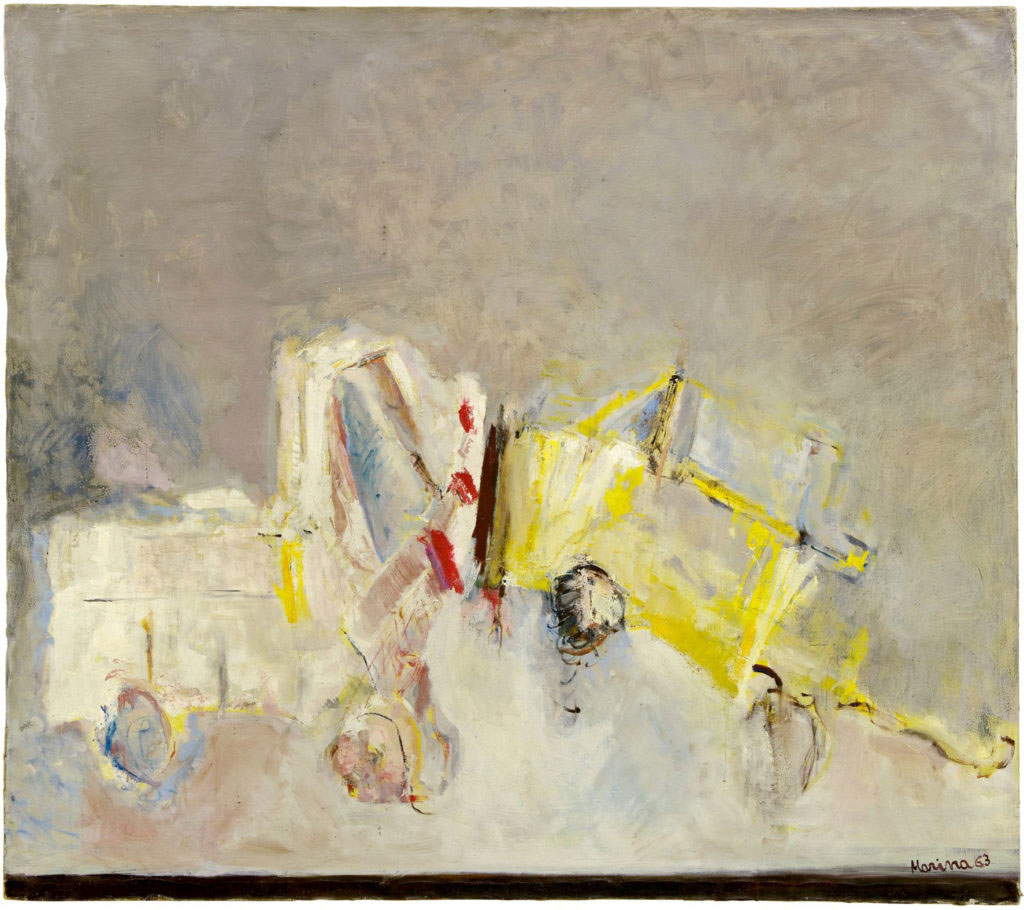

The theme of destruction has interested Abramovi�?’s career not only in reference to war. Already in her very first pictorial works, such as the 1963 Truck Accident series, the young artist investigated the dissolution of matter and color through the depiction of a truck accident. In her autobiography she states, “In the academy, I used to paint in an academic style: nudes, still lifes, portraits and landscapes. But I also began to have new ideas. For example, I was fascinated by traffic accidents, and I had the inspiration (it was the first time it happened to me) to paint pictures on this subject. I would cut out pictures of car and railroad crashes from newspapers; and I took advantage of the connections my father had in the police to go to the various barracks and ask if any big accident had happened. Then I would go to the scene and shoot and sketch. But it was difficult to translate on canvas the violence and immediacy of those disasters.”

The dissolution, the breaking down of certain barriers, the crossing of the limits of physical and psychic endurance have always been at the center of the performances of she who today is undoubtedly one of the most famous artists in the world. From her very first acts, such as Rhythm 5, Rhythm 0, Rhythm 10 and Thomas Lips, the artist completely changed the way performance was constructed in the early 1970s. Unlike artists such as Chris Burden, Vito Acconci, Adrian Piper, and Dennis Oppenheim, who worked for the public, Marina Abramovi�? has always made her works with the public, and unlike her contemporaries working in the United States, in a liberal, capitalist system, she was able to explore performance in a Belgrade still under Tito’s communist regime. The audience was always invited to participate in her performances with the intention of creating a real exchange of constructive energy between the artist and the audience, just as happens on a theater stage, with the difference that what happens in a performance is real, while in the theater it is fiction. In 1974, for the Rhythm 5 performance, the audience intervened directly and by emergency: Abramovi�? was almost suffocating in the flames of the gardent five-pointed wooden star to which the artist had set fire and within whose perimeter she had placed herself by lying on the ground. It was in this case a true dissolution of the boundary, in that case necessary, between those who had performed the performance and those who were its spectators. In another of his celebrated works, namely Rhythm 0, the audience was invited to participate, and this interaction brought serious consequences to the young Marina’s body, almost leading to her death again. Rhythm 0 was realized in 1975 at Studio Morra in Naples: the performance involved the artist standing still as an object in front of a table on which there were seventy-two objects, including a hammer, a saw, a fork, a rose, a bell, a small bell, a pen, a penknife, a mirror, pins, lipstick, and a gun with a bullet next to it. These objects could be used at will on her, who assumed all responsibility during the six-hour performance. For the first few hours nothing much happened, as (as Abramovi�? herself reports) the audience must have been intimidated, wondering what was going on. As the hours went by, the people there began to change their approach toward the artist: they stripped her naked, made her assume various positions, humiliated her, and even reached the point of physical harm. The climax was reached when one of the spectators grabbed the gun, inserted the bullet and put it in the artist’s hand, ready to pull the trigger. At that point the performance was stopped as it had already become too dangerous for the young artist’s life.

In Abramovi�?’s performances, destruction has also meant staging the end of a love affair, as was the case with one of her most beautiful (and most complex) works ever, perhaps the best created together with her partner and artist Ulay to enshrine once and forever the end of their love. The performance in question is The Lovers from 1988, by which time her history with Ulay had broken down. This was the last project the two made together and involved the two of them crossing the Great Wall of China in opposite directions and then meeting halfway, after traveling 2,500 kilometers, and saying goodbye: Marina was to start the journey from the eastern, female end of the Wall (the Bohai Gulf in the Yellow Sea) and Ulay from the western, male end, the Jiayu Pass in the Gobi Desert. “We finally met on June 27, 1988, three months after we started, in Erlang Shen, Shennu, Shaanxi Province. [ ]. I was heartbroken. But my tears were not only for the end of our relationship. We had accomplished a colossal feat. In my eyes, my part had an epic dimension: a long ordeal that was finally over. I felt as relieved as I did sad.”

Marina Abramovi�?’s performances, which several times in the long span of her career have been able to decline destruction in different aspects, themselves represent the dissolution and abatement of human fears: suffering, abandonment, loneliness, pain, death. Abramovi�? confronts these fears and tries in some way to break them down, to overcome them, calling the audience to participate in her undertaking. For this artist, in fact, art must be disturbing and must ask questions. It must not just be something that reflects everyday life: magazines already do that. Larte must have a spiritual value that opens some doors of human consciousness and leads people to reflection. Because man is destroying himself, and larte takes on the task, according to Abramovi�?, of changing the ideology of society.

The author of this article: Francesca Della Ventura

Ha studiato storia dell'arte (triennale, magistrale e scuola di specializzazione) in Italia e ha lavorato per alcuni anni come curatrice freelancer e collaboratrice presso il Dipartimento dei Beni Storici, Artistici ed Etnoantropologici del Molise (2012-2014). Dal 2014 risiede in Germania dove ha collaborato con diverse gallerie d'arte e istituzioni culturali tra Colonia e Düsselorf. Dallo stesso anno svolge un dottorato di ricerca in storia dell'arte contemporanea all'Università di Colonia con una tesi sul ritorno all'arte figurativa negli anni Ottanta in Germania e Italia. Nel 2018 è stata ricercatrice presso l'Universidad Autonoma di Madrid. Ha scritto sull'identità tedesca e italiana nell'arte contemporanea e nella politica, sul cinema tedesco e italiano del dopoguerra e grazie a diverse borse di studio D.A.A.D. ha presentato la sua ricerca a livello internazionale. Attualmente i suoi temi di ricerca riguardano l’arte degli anni Ottanta, in particolar modo quella femminista. Dal 2020 è entrata a far parte del gruppo di ricerca dell’Universitá di Bonn “Contemporary Asymmetrical Dependencies” con un progetto di ricerca sulla costruzione dei nuovi musei e delle condizioni di dipendenza asimmetrica dei lavoratori migranti nell’isola di Saadyat ad Abu Dhabi. Nell'ottobre 2020 ha fondato inWomen.Gallery, galleria online, sostenibile e per artiste. Dal 2017 lavora come giornalista d'arte per la rivista online e cartacea Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.