by Ilaria Baratta , published on 01/02/2021

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Duchess of Parma and Piacenza between 1547 and 1586, Margaret of Austria, daughter of Emperor Charles V, initiated the construction of one of the most important buildings of the second half of the 16th century in Italy, the Palazzo Farnese in Piacenza, now home to the civic museums.

Born out of an adulterous relationship of Charles V with Giovanna van der Gheynst, daughter of a tapestry maker in the Flemish town of Oudenaarde, Margaret of Austria (Oudernaaarde, 1522 - Ortona, 1586), future duchess of Parma and Piacenza, was the one responsible for the construction of the Palazzo Farnese, now the headquarters of the Civic Museums of Piacenza. The emperor recognized her as his legitimate daughter and named her after her aunt, Margaret of Habsburg, governor of the Netherlands. A painting preserved at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent made by Belgian painter Théodore Joseph Canneel (Ghent, 1817 - 1892) in 1844 depicts in a genre scene Charles V and Joan van der Gheynst in front of the cradle of their daughter Margaret, who sleeps peacefully, while her mother arranges her cover turning a look of complicity to the emperor; he, too, standing next to the commoner, tenderly observes the child. The painter used to make portraits, historical genre works and genre scenes, and in this canvas, rich in detail, he soberly depicts a somewhat romanticized moment in the emperor’s intimate life.

However, the child was educated in Brussels, first by the governor of the Netherlands and later by Mary of Hungary, sister of Charles V, receiving an education as a true princess, both in reading and writing and in music and dance, and sharing with Mary the same passion for horses. While still very young, on the emperor’s legitimate daughter, reasoning began for possible strategies of imperial policy through the latter’s union with important members of the most famous families and lordships of the time. Names were mentioned of Ercole d’Este, who would have united her with the court of Ferrara, or Federico Gonzaga, marquis of Mantua, but in the end two pontiffs succeeded in tying Margaret of Austria to prominent members of their families of origin. First, Clement VII, born Giulio de’ Medici, a member of the noble Florentine lineage, managed to unite in marriage his nephew Alessandro de’ Medici, duke of Florence, and the daughter of Charles V: before the wedding was celebrated, the duke had to wait a few years as his future wife was still too young, until June 1536. It was an unhappy union, because of her husband’s unruly character, and also very short-lived because the following year Alessandro de’ Medici was assassinated by his cousin Lorenzino de’ Medici, who misled him with the idea of a night of love. Meanwhile, Margaret had received the fiefs of the States of Abruzzi as a dowry from her father.

|

| Théodore Joseph Canneel, Emperor Charles V and Joan van der Gheynst with their daughter Margaret in the cradle (1844; oil on canvas, 108.2 x 80.5 cm; Ghent, Museum voor Schone Kunsten) |

Widowed, she was still available for other marriage plans: in 1538 Pope Paul III, born Alessandro Farnese, obtained consent to give her in marriage his very young nephew Ottavio Farnese (Valentano, 1524 - Parma, 1586), son of his son Pier Luigi. Margherita was just sixteen years old, but her future second husband was even younger than she: after having been duchess of Florence through her union with her first husband, the young woman did not see Ottavio as suitable for her at all, even though the pontiff had showered his nephew with honors and offices, plus she did not love him. Nevertheless, the wedding was celebrated by Paul III himself in the Sistine Chapel, and the bride came to Rome dressed in black to make her disappointment and unhappiness even more manifest. Margaret even refused to live together with her new groom and moved to one of the Medici-owned palaces in Rome, Palazzo Medici in Monte Mario, which she named Palazzo Madama (this is what Margaret of Austria also called herself: Madama), assisted spiritually by Ignatius of Loyola. In the palace, now the seat of the Italian Senate, which Margaret had acquired from widowhood following the death of Alessandro de’ Medici, Ottavio Farnese was not welcome; indeed, the Madama wished to stay as far away from it as possible, and even her conjugal duties at first were not respected, causing considerable chatter in Roman circles and concern on the part of both her father Charles V and members of the Farnese family. However, later, perhaps advised by Ignatius of Loyola, the marriage was consummated, although Margaret still preferred to stay away from her husband, and in 1545 twins, Charles and Alexander, were born. Moreover, the Equestrian Monument in Piacenza’s central Piazza Cavalli is dedicated to the latter: a Baroque bronze sculpture by Francesco Mochi (Montevarchi, 1580 - Rome, 1654) in 1625, depicting the famous Farnese condottiere on horseback.

|

| Piacenza, Piazza Cavalli |

Things began to change at that point, in part because of the honor Ottavio had won during Charles V’s expedition to Algiers.

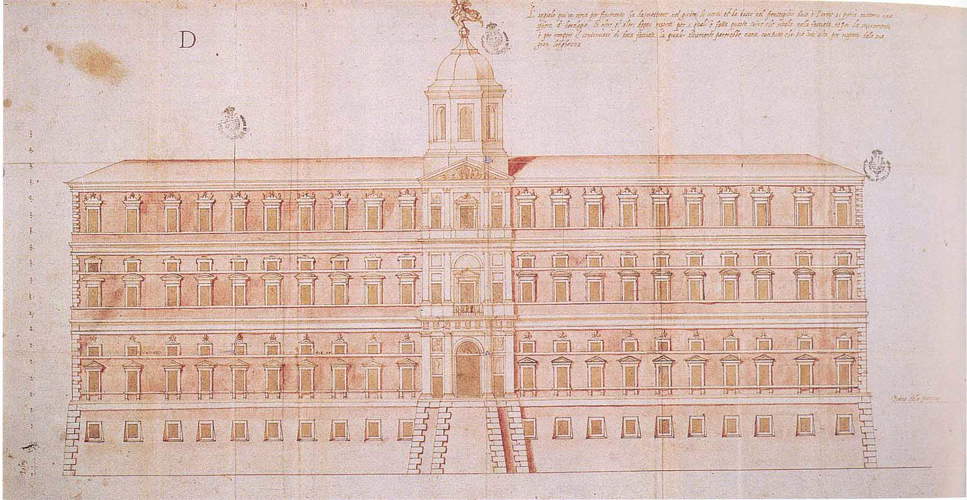

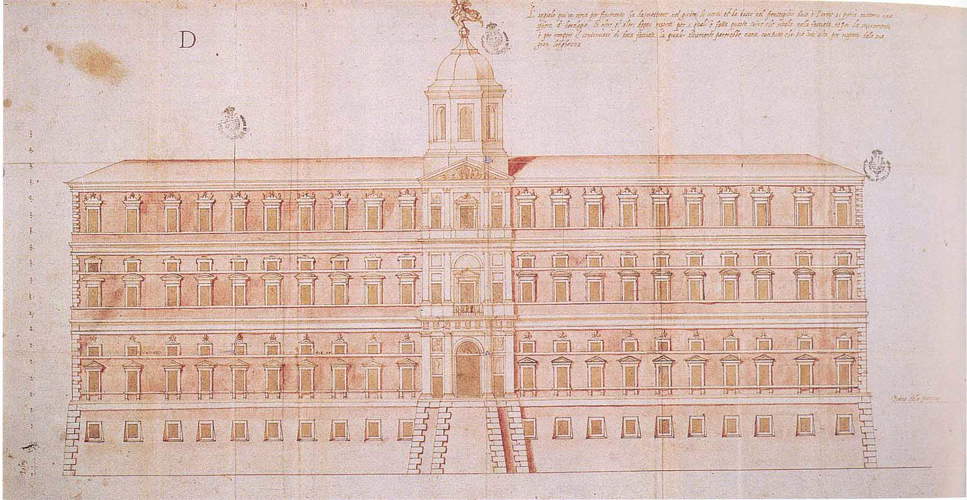

The Duchy of Parma and Piacenza was founded in 1545 at the behest of Paul III to be given to his son Pier Luigi, but the latter was killed two years later in a conspiracy because he was considered tyrannical, and to assume the titles of duke and duchess of Parma and Piacenza were therefore Ottavio and Margherita. Following the War of Parma, Charles V ordered Margaret’s half-brother Philip II of Spain to place Margaret’s son Alexander under the guardianship of the latter, and she personally accompanied him to Brussels. Philip II was to appoint her two-three years later, in 1559, as governor of the Netherlands, just like her aunt Margaret of Austria, to preserve those territories, but in the meantime Madame settled alone, without her husband, in Piacenza, giving birth to her official residence: the Palazzo Farnese. In the Treatise on Architecture by Francesco de Marchi, a figure who remained in contact with the Madama for many years, we read: “Madama Margherita of Austria who gave principle to a palace in Piacenza at the old citadel, which palace is estimated to cost three hundred thousand scudi before it is finished; when she wanted to begin building it she had a Francesco Pacchiotto da Urbino famous architect, who made the design, then the model; although she saw both, she did not want to trust and sent for another architect though of great name and good fame who was Vignola.” The project, originally entrusted to Francesco Paciotto, dates back to 1558 and planned to build the palace on the foundations of the Visconti castle, erected on the edge of the city by Galeazzo Visconti in the mid-14th century. Later, starting in 1561, the commission was given to Jacopo Barozzi known as il Vignola (Vignola, 1507 - Rome, 1573), due to the unreliability of the former and the problems that arose regarding the use of the ancient foundations. Vignola had already worked for the Farnese family at Caprarola on the villa commissioned by Alessandro Farnese and, having abandoned the idea of erecting the new Piacenza residence on pre-existing foundations, chose toenlarge the four wings of the building and increase the size of the courtyard. Work came to a halt, unfinished and almost half the size of the actual project, in 1602 due to lack of necessary funds. In addition to serving as Margaret’s personal residence, the palace was to make manifest the great power of the Farnese family. The many windows on the exterior hint at the large number of rooms inside and the consequent monumentality of the entire building, and the arched niches facing the courtyard give the outdoor space a larger and more airy appearance.

Now home to the Civic Museums of Piacenza, Palazzo Farnese houses splendid masterpieces of art, including paintings, sculptures, frescoes and ceramics, and important archaeological finds (and, in this regard, the new Roman section will also be inaugurated soon), such as the Etruscan Liver, a bronze model of a sheep’s liver found around Piacenza in 1877 that constitutes rare evidence of Etruscan religious rites and deities. Also worth mentioning are Botticelli’s Tondo depicting the Madonna praying to the Child with St. John the Baptist, and the Fasti Farnesiani, or representations celebrating the most significant events in which the Farnese family was involved: the first cycle is dedicated to the events of Paul III and Alessandro Farnese. In addition, the palace is also home to the Carriage Museum, one of the best known and most prestigious of its kind in Italy, with a collection ranging from the 18th century to the invention of motor transportation.

|

| Piacenza, Palazzo Farnese. Ph. Davide De Paoli |

|

| Piacenza, Palazzo Farnese. Ph. Marco Trabacchi |

|

| Piacenza, Palazzo Farnese, the remaining portion of the Visconti castle. Ph. Szeder László |

|

| Piacenza, Palazzo Farnese, the inner courtyard. Ph. Stefano Stabile |

|

| The wooden model of Palazzo Farnese made by architect Enrico Bergonzoni, showing how the palace would have looked if it had been completed |

|

| The design for the facade of Palazzo Farnese in a drawing by Giacinto Vignola, son of Jacopo Barozzi |

|

| Palazzo Farnese, the Picture Gallery |

|

| Palazzo Farnese, the hall of the Fasti Farnesiani |

|

| Etruscan art, Liver of Piacenza (2nd-1st century B.C.; bronze, 12.6 x 7.6 x 6 cm; Piacenza, Musei Civici di Palazzo Farnese) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Madonna Adoring the Child with St. John the Baptist (c. 1475-1480; tempera on panel; Piacenza, Musei Civici di Palazzo Farnese) |

|

| The Carriage Museum |

We might say, then, that the existence of such a grandiose museum venue in the city is due to Margaret of Austria, a female Renaissance figure whose life was marked by marital unhappiness, destined too young to be united in marriage with powerful families, and by many changes and relocations: from the Spanish monarchy of which she was a descendant, being the daughter of Charles V, to the Medici court to the Farnese court, via the Netherlands, of which she was governor. Among important appointments, Madama elected Piacenza as her favorite city, where she loved to live and where she wanted to be buried.

The last years of her life she spent, having returned from Flanders, in her Abruzzi states, governing them directly, between Cittaducale and L’Aquila; in 1582 she bought Ortona from the prince of Sulmona and in this locality she had her residence built, although she never lived there, since when she died in 1586 the building was not yet finished.

Her body was transported to Piacenza, as she wished according to her will, and buried in the town church of San Sisto (the same church for which Raphael had made the Sistine Madonna between 1512 and 1513), where still today one can admire, between the two apses at the end of the main transept, the funeral monument dedicated to her, designed by Simone Moschino (Orvieto, 1553 - Parma, 1610) and begun in 1593.

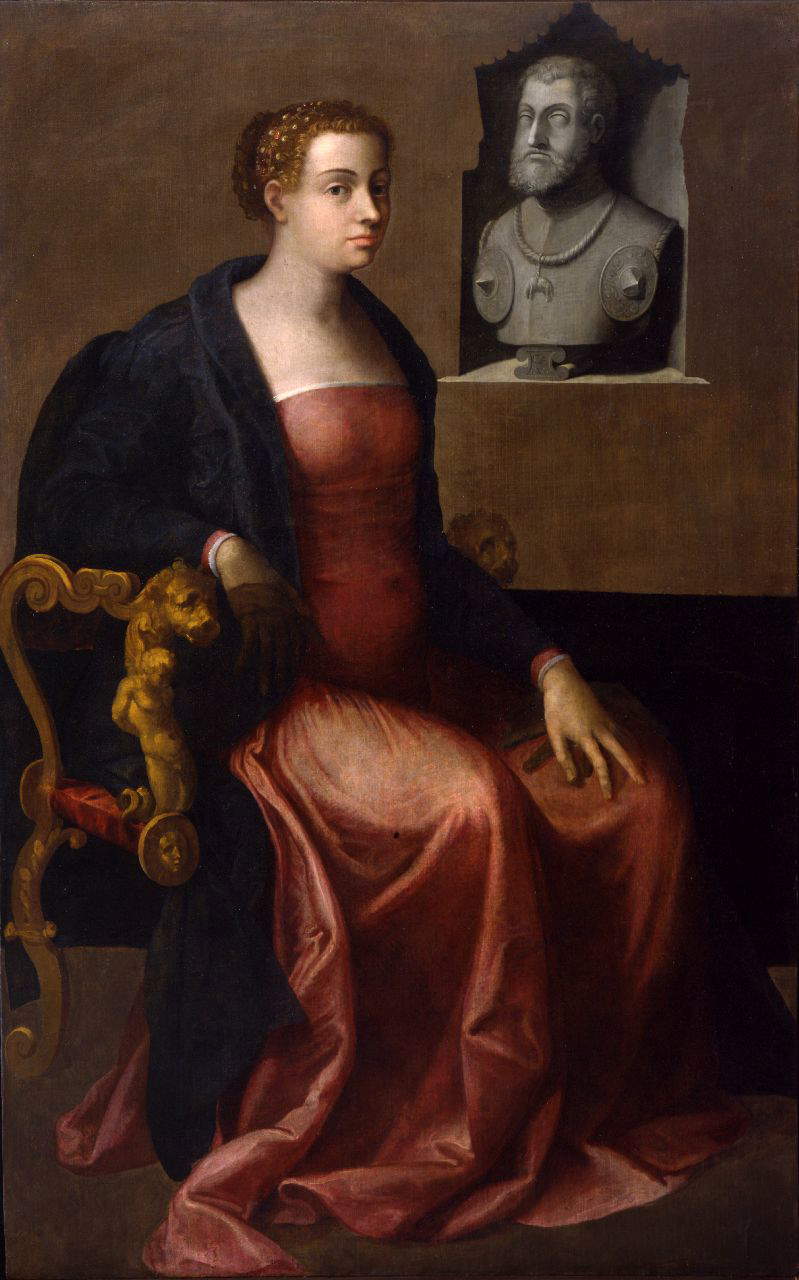

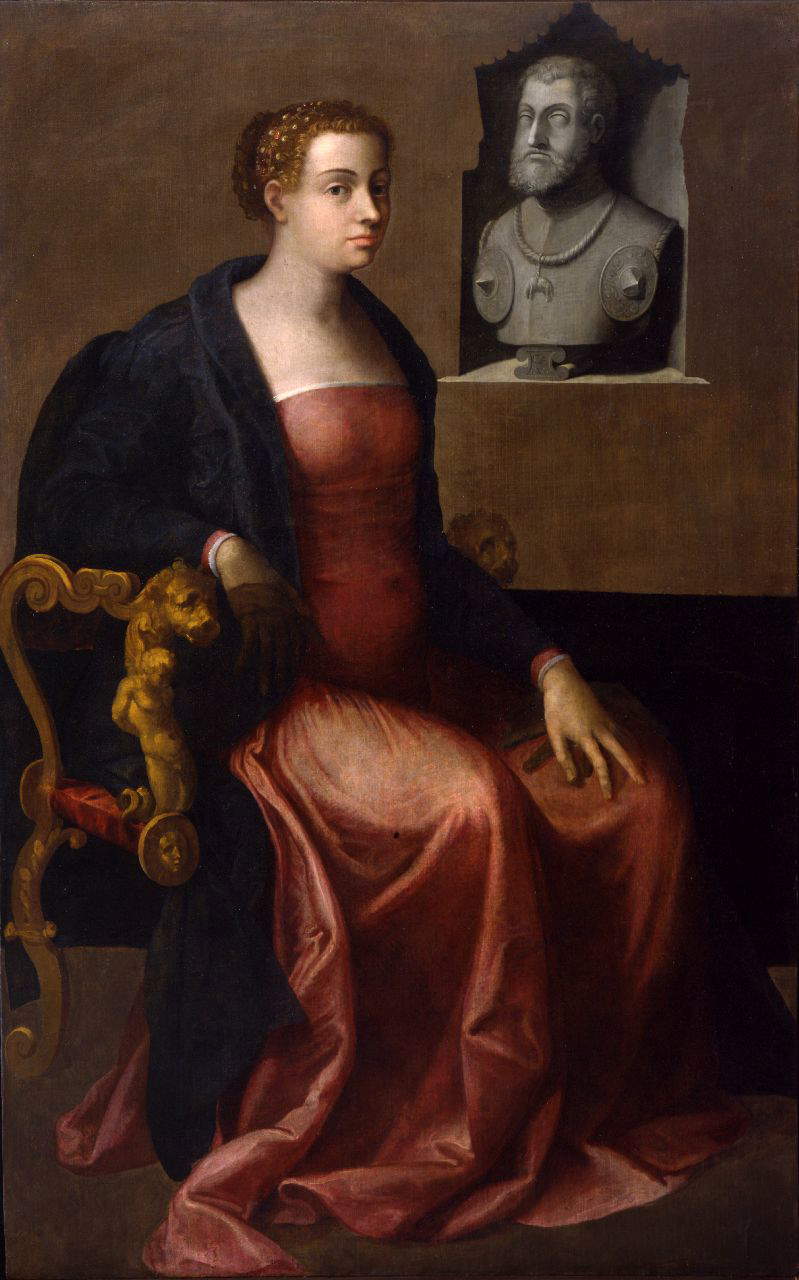

There are two portraits of Margaret of Austria preserved in as many collections in Parma: one at the Pinacoteca Stuard made by the Dutch painter Anthonius Mor (Utrecht, 1520 - Antwerp, 1576/1578), who portrayed her almost full-length as she turns her gaze to the observer. Dressed in ample robes according to the fashion of the time and with her hair up, the woman rests her left hand on a table covered with green cloth and in her right hand holds a pair of gloves. Another painting, belonging to the collections of the Galleria Nazionale di Parma and attributed to Sebastiano del Piombo (Venice, 1485 - Rome, 1547) or nearby masters, depicts her in a state of pregnancy, seated three-quarter-length next to a niche with the bust of her father Charles V in the form of an antique statue. Elements of submission seem to prevail here: the glove of her right hand, the one symbolizing power, is almost slipped off, and the armrest of the chair on which she is seated probably depicts, under a lion’s head, Prometheus with his hands tied behind his back, while a Medusa head triumphs at his feet. It is a portrait that underscores the surrender before her father’s wishes and the unhappiness that accompanied her for years to fulfill her father’s strategies of imperial policy.

|

| Ortona, Farnese Palace. Ph. Istituzione Palazzo Farnese Ortona |

|

| Simone Moschino, Funeral Monument of Margaret of Austria (1593; Piacenza, San Sisto) |

|

| Anthonius Mor, Portrait of Margaret of Austria (1562-1573; oil on canvas, 81.5 x 106 cm; Parma, Pinacoteca Stuard) |

|

| Attributed to Sebastiano del Piombo, Portrait of Margaret of Austria (c. 1545; oil on canvas, 169.7 x 105.3 cm; Parma, Complesso della Pilotta, Galleria Nazionale) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.