Marc Chagall, the "White Crucifixion": a cry, still relevant today, against Nazi madness (and all extremism)

“They never understood who this Jesus really was. One of our most loving rabbis who always came to the aid of the needy and persecuted. They attributed too many ruler’s insignia to him. He was considered a preacher with strong rules. To me he is the archetypal Jewish martyr of all time.” These are the words of one of the most significant artists of the twentieth century, a Russian painter of Jewish origin who recounted through his evocative paintings the difficult historical condition in which he lived and, in particular, that tragic period marked by the racial massacres of World War II: Marc Chagall (Vitebsk, 1887 - Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 1985).

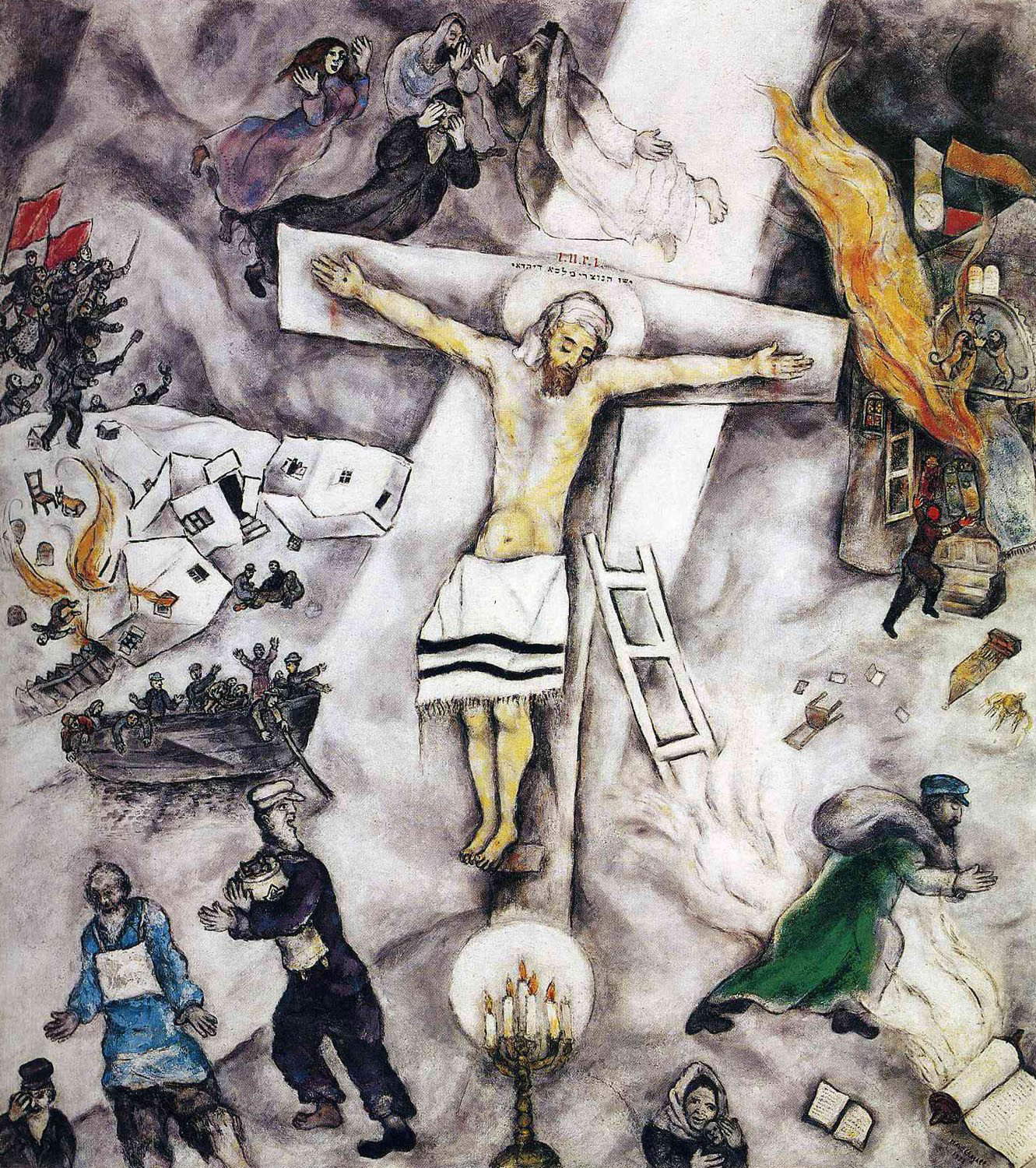

“This is what I understood when I first used the image [...]. I was under the influence of the pogroms. Then I painted and drew it in depictions of ghettos, surrounded by Jewish torments, by Jewish mothers running around terrified holding little children,” the artist said. Chagall was probably referring to his White Crucifixion, made in 1938, in which he depicted in an unusual way a mixture of the Christian and Jewish religions: as stated, the Jewish painter believed in Jesus’ belonging to the persecuted Jewish people, whom he placed in his Crucifixions, for the most part, at the center of the composition. Moreover, following his Jewish origins, he depicted the Crucifixion from the point of view of a Jew: as critic Franz Meyer noted, the relationship of the Christ figure to the world is quite different from that of Christian crucifixions. In the latter, all pain is concentrated in and on Christ, who is mourned at the foot of the cross by the Virgin, Magdalene, and St. John. In Chagall’s Crucifixions, too, all the pain of the world is reflected in the events of the cross, but it remains a perpetual human destiny that is not resolved by Christ’s death. In fact, several scenes are depicted around the cross that refer to Jewish beliefs and portray a world of pain and death, of violence and abuse committed against the Jewish population.

|

| Marc Chagall, White Crucifixion (1938; oil on canvas, 154.6 x 140 cm; Chicago, Art Institute) |

|

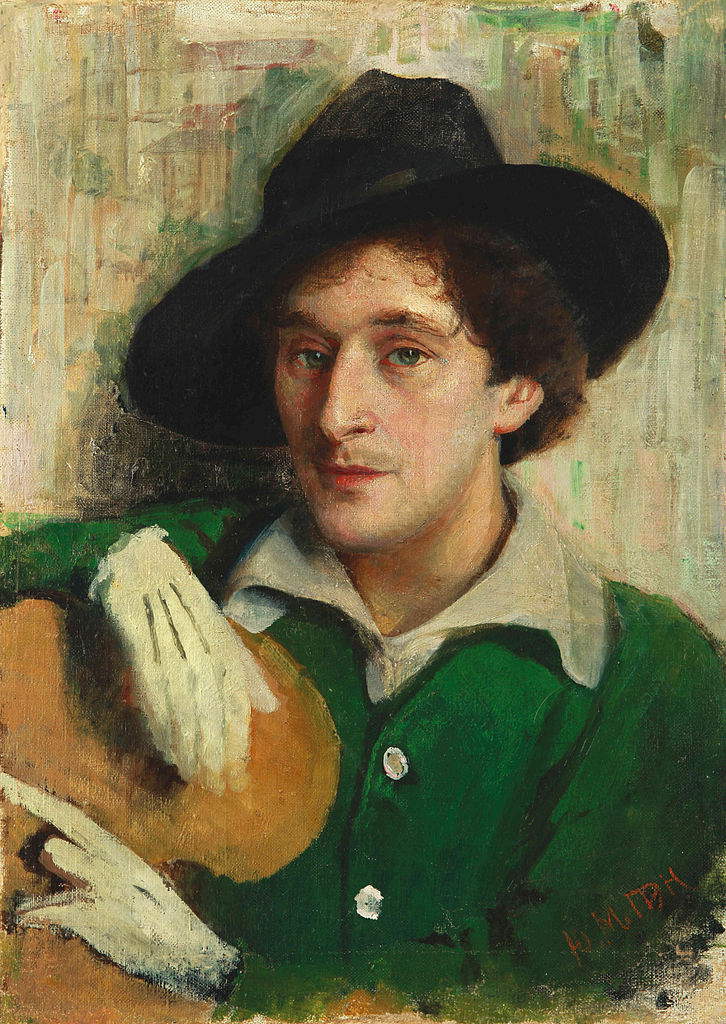

| Yury (Yehuda) Pen, Portrait of Marc Chagall (1914; oil on canvas, 54 x 41 cm; Minsk, National Museum of Art) |

The artist was born in the small town of Vitebsk, in present-day Belarus, to a family of the Jewish faith, and his origins caused consequences in his life, especially when Nazism seized power in Germany and anti-Semitic laws were spread. In that discriminatory climate all his works were confiscated from German museums and the painter, because of his “race,” was forced to leave Paris during World War II and emigrate to the United States where he settled from 1941 to 1948. The desire to depict human pain, caused by the discrimination and brutality perpetrated on the Jewish race by those who considered themselves to be of a superior race since they were “pure,” was accentuated in Chagall as a result of the repeated pogroms, the Russian term for the violent devastation suffered by Jews at the hands of local populations that occurred on Russian soil and in other areas of the world. During these acts of violence, Jews were subjected to assaults, which often ended in death, and looting and destruction of their property and related buildings.

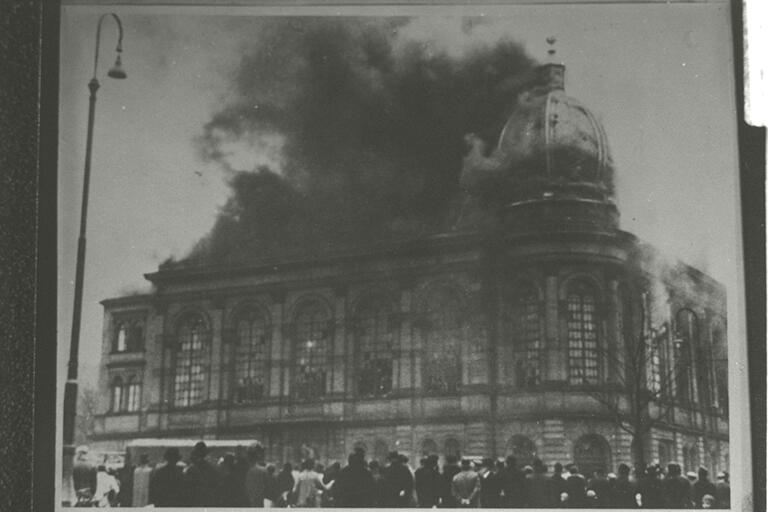

With the rise of Nazism in Germany in 1933, violence had become, according to this ideology, a tool to restore order, to eliminate everything that belonged to the inferior race. In the wide and extensive trail of pogroms that were carried out, the most tragic and devastating was the one commonly known as Kristallnacht, the Crystal Night, which occurred on the night of November 9-10, 1938. The streets of the cities of Germany, Austria and the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia were a heap of shattered glass (hence the term Kristallnacht): the windows of Jewish-owned houses, synagogues and stores were destroyed, synagogues burned and looted, store warehouses looted and storefronts shattered, and Jewish cemeteries desecrated. People of the “Jewish race,” particularly young people, were arrested: rapes, suicides and public humiliations, as well as attacks on their homes, are witnessed. After arrest, they were imprisoned in concentration camps in Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen. Moreover, these events were accompanied in the following days by laws through which Jews were deprived of their property in order to surrender it to the Nazis, were excluded from many professions, schools, public transportation, and removed from theaters, cinemas, and public life.

Crystal Night is remembered as one of the highlights of Jewish persecution: a night of violence for the sole reason of belonging to a different race. The night that marked a turning point toward a world characterized increasingly by hatred and death. And it was in conjunction with Kristallnacht that Marc Chagall created his White Crucifixion. The designation “white” is due to the prevalence of the color white in the background of the painting, which also has shades in shades of gray, lighter towards the bottom and darker towards the top.

|

| Jewish-owned store in Magdeburg destroyed during Crystal Night (November 1938; b/w photograph, Berlin, Bundesarchiv) |

|

| The old Ohel Jakob synagogue in Munich destroyed during Crystal Night (November 1938; b/w photograph; Private collection) |

|

| The Börneplatz synagogue in Frankfurt am Main destroyed during Crystal Night (November 1938; b/w photograph; New York, Center for Jewish History) |

The work, as has already been stated, is constructed with images and re-enactments that come from the Christian and Jewish worlds in order to imprint on the canvas the suffering, violence and abuse suffered by Jews. First of all, from the crucified Christ, who although the Christian symbol par excellence, becomes here, and in most of Chagall’s Crucifixions, the archetype of the Jewish martyr. Jesus on the cross is placed by the artist in the center of the composition, illuminated by a wide beam of white light. On his waist he wears a tallit, the Jewish prayer shawl, and his head is not surrounded, as in usual Christian iconography, by the crown of thorns, but by a white cloth. The cross is inscribed twice with the inscription INRI, a Latin acronym for Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum, or Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews: red in Gothic letters to recall the Nazis’ anti-Semitic pamphlets and the color of blood, and black in Hebrew letters written in full. At the base of the cross, which illuminates it, is a Menorah, the seven-armed, oil-fueled candelabra: it is one of the most recurring symbols of Judaism and its very name refers to light; according to the Jewish religion, it was built by Moses for the Ark of the Covenant, that is, the gold-covered chest that the latter made at God’s behest in order to guard his testimony, the Tablets of the Law. The Menorah was later part of the sacred furnishings of the Temple in Jerusalem. Leaning against the cross was a ladder: used for the very act of crucifixion, this probably indicates the link between heaven and earth.

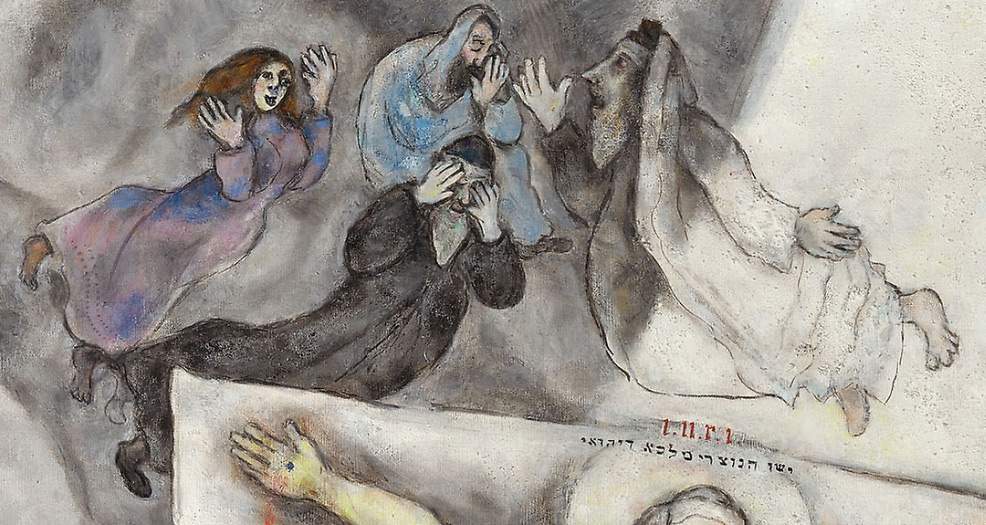

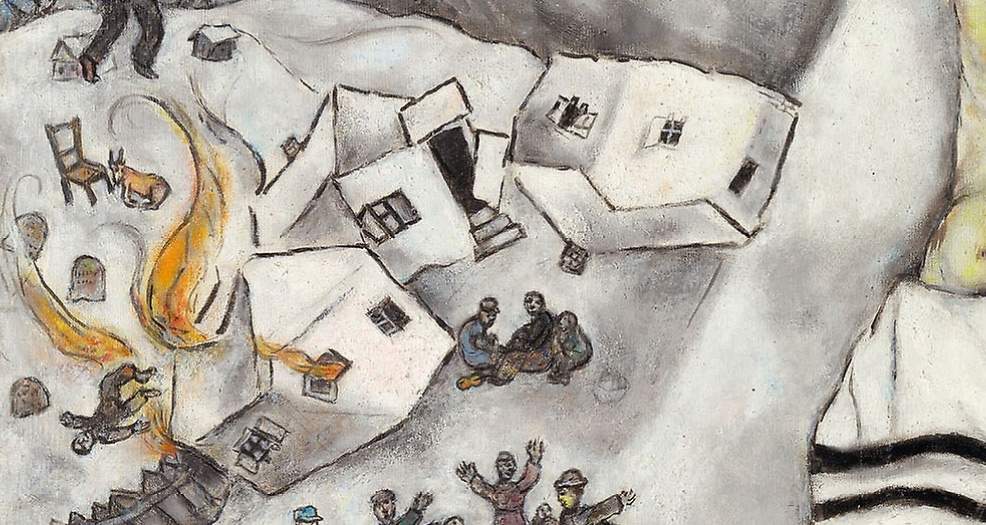

Around the crucified Jesus, Chagall depicted various scenes: counterclockwise, three men and a woman are seen above the cross, instead of the usual angels, expressing all their despair by weeping, bringing their hands to their faces and praying for the widespread violence and suffering to come to an end as soon as possible. Next, houses torn apart by flames and even toppled over are depicted, from inside which some frightened inhabitants emerged. The Jewish village has been set ablaze by soldiers who, armed, stand just outside the town and proudly raise red flags: the event thus can be traced back to a pogrom on Russian territory, and the red color of the flags indicates membership in Stalin’s communism. A little further down, the artist painted a boat filled with Jewish refugees who are trying to drop anchor to save themselves and dock on safe land. It is a scene that is still very relevant, despite the fact that eighty years have passed since the painting was made, a scene that expresses fleeing the homelands with the hope of saving their lives in parts of the world untainted by war and devastation. In the lower left corner, three elderly men are trying to protect, by rescuing it from undoubted destruction, a Torah, the laws and commandments received on Mount Sinai; in Jewish tradition, Torah denotes the first five books of the Bible, from Genesis to the death of Moses. One of the three fleeing men, in the first redaction of the painting, wore a sign around his neck that read “Ich bin Jude,” “I am a Jew,” a further sign of recognition.

|

| Marc Chagall, White Crucifixion, detail, the despairing figures in the upper register |

|

| Marc Chagall, White Crucifixion, detail, the destroyed village |

|

| Marc Chagall, White Crucifixion, detail, the boat of refugees |

|

| Marc Chagall, White Crucifixion, detail, the rescue of the Torah and the Menorah |

|

| Marc Chagall, White Crucifixion, detail, the mother with the child |

|

| Marc Chagall, White Crucifixion, detail, the synagogue in flames |

Continuing on, one notices a mother clutching her small son to her as a sign of protection and apparently covering his small face so that he would not perceive and know the horrors of war. Next to the woman, a man dressed in green is trying to protect the books of the Holy Scripture from the white fire, which is spreading from the lower right corner of the canvas, by putting them inside the sack he carries on his shoulders. Scattered on the ground are some objects. The last scene depicted is that of a synagogue from which high flames are coming out: men are attempting to take from them what is kept inside the building; the Tablets of the Law and the Star of David, a sign of belonging to the Jewish creed, are visible between two lions.

The White Crucifixion, now housed at theArt Institute of Chicago, is a thought-provoking painting: through art, Chagall intends to put on canvas what he himself saw, all that he witnessed. By depicting the constant pogroms that were occurring more and more in his time, he meant to represent how far hatred can go and to leave a testimony to the generations contemporary with him and to future generations. A lesson that should not be limited to Memorial Day, but rather to be held firmly in mind every day so as not to repeat the horrors and mistakes of the past.

Reference bibliography

- Roger Simon, The Touch of the Past: Remembrance, Learning and Ethics, Springer, 2016

- Pierre-Emmanuel Dauzat, Judas. From the Gospel to the Holocaust, Arkeios Editions, 2008

- Jeremy Cohen, Christ Killers, The Jews and the Passion from the Bible to the Big Screen, Oxford University Press, 2007

- Piero Stefani, The Biblical Roots of Western Culture, Pearson Italy, 2004

- Michael Alan Signer, Humanity at the Limit: The Impact of the Holocaust Experience on Jews and Christians, Indiana University Press, 2000

- Ingo Walther, Rainer Metzger, Chagall, Taschen, 2000

- Raissa Maritain, The Great Friends, Vita e Pensiero, 1991

- Ziva Amishai-Maisels, Chagall’s "White Crucifixion," Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, vol. 17, no. 2 (1991), pp. 138-153+180-181

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.