Man, schizophrenic, artist. Remembering Carlo Zinelli 50 years after his death

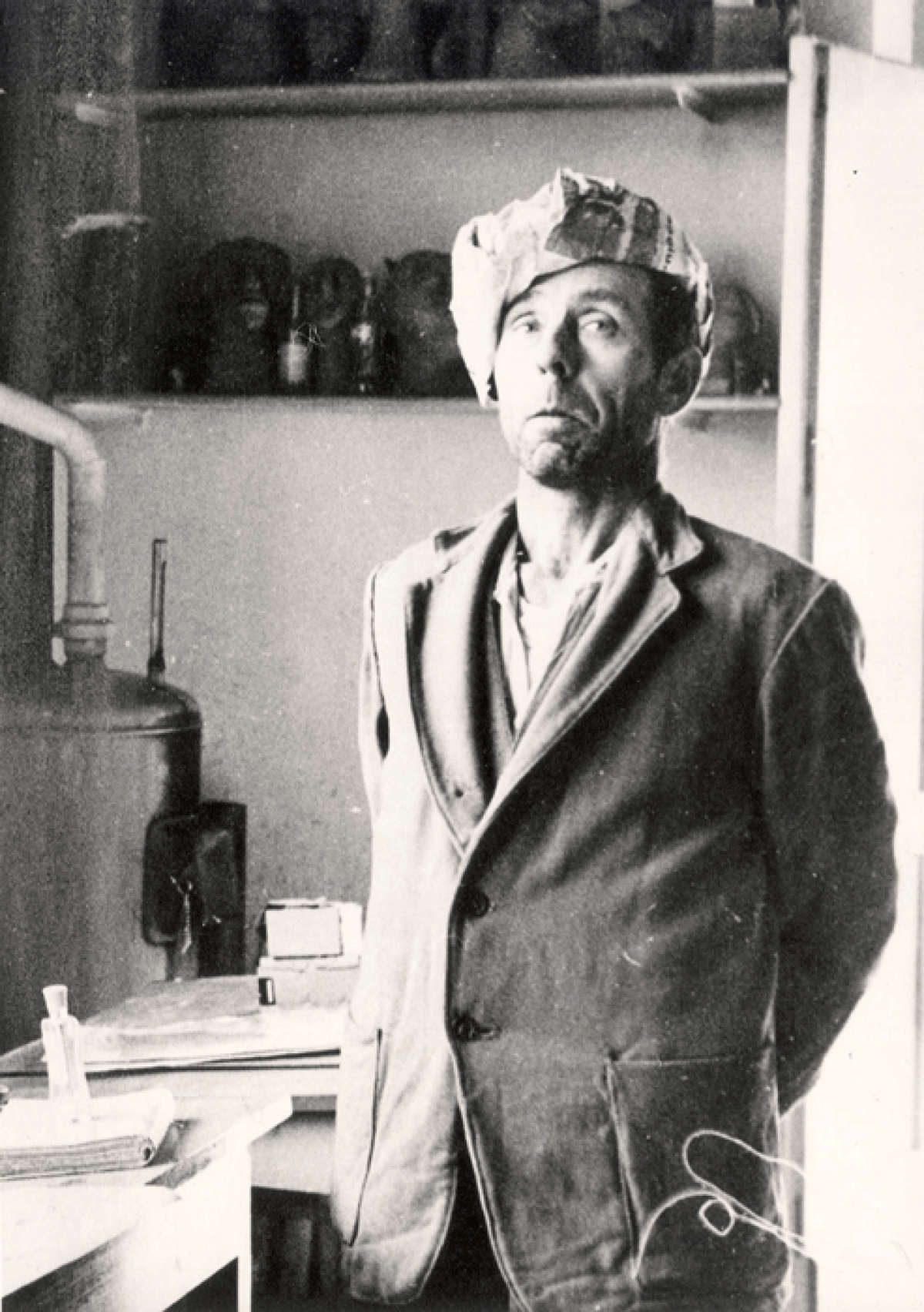

“He was an extraordinary madman”: the words of Vittorino Andreoli, the psychiatrist who has cared for Carlo Zinelli since 1959 and to whom we basically owe our knowledge of this artist, who spent a large part of his life interned in the San Giacomo della Tomba asylum in Verona (the era is the one before the 1978 Basaglia Law, which transformed the way psychiatric patients were cared for and the names of the institutions). Zinelli was born in San Giovanni Lupatoto (Verona) in 1916 and died on January 27, 1974 in a hospital in Chievo: he was one of the most significant painters among those included in the constellation of Art Brut as it was conceived by Jean Dubuffet.

Since the time of his “discovery,” Zinelli’s works have been featured in all exhibitions intended to explore the delicate and intriguing relationship between art and madness; among the most recent exhibitions that gave space to this painter was L’arte inquieta. The Urgency of Creation, staged at Palazzo Magnani in Reggio Emilia between 2022 and 2023, and in the same year a monographic exhibition was staged at Palazzo Te in Mantua, curated by Luca Massimo Barbero. But fundamental to Zinelli’s knowledge was the publication in 2002 of the general catalog edited by Vittorino Andreoli and Sergio Marinelli, on whose pages nearly 1,900 pieces1 are reproduced.

From rural life to war and then to the atelier

Carlo Zinelli grew up in a rural setting in the province of Verona. Due to the straitened finances of his large family, as a boy he was given as a “famiglio” (family man) to the tenants of a nearby farm, where he worked in exchange for room and board. “Of a solitary and sensitive disposition, he spent his boyhood caring lovingly for the farm animals, especially the dog, and observing the existence of insects, birds and chickens, beings that would later populate his creative imagination,” Roberta Serpolli writes in the biographical profile published by Treccani2. Once an adult, he was sent by his father to work at the municipal slaughterhouse in Verona, and the new employment allowed him to achieve some economic comfort; during that period he also manifested his first flashes of creativity, depicting “on the walls of the kitchen a flowering branch and a large figure of a bird,” Serpolli recounts again.

In 1938 Carlo moved to Trent to fulfill his conscription obligations, enlisted as an infantryman in the Alpine Corps, and the following year had to leave for Spain, where the bloody civil war between nationalist and republican forces was still going on. Repatriated after only two months, Zinelli began to suffer from persecution mania and episodes of delirium and terror that led to his initial hospitalization at the military hospital in Verona. His final discharge from the army did not resolve the problems and traumas he experienced during the conflict, which by no means ceased to resurface, aided moreover by Italy’s participation in World War II. In 1947 Charles was then permanently committed to the San Giacomo alla Tomba psychiatric hospital in Verona, where he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. “He had split,” Vittorino Andreoli comments, “He did not want to know how to be a socially inserted man. He decided this while fighting on a war front, and here, rather than kill, he thought it was better to go mad. ”3

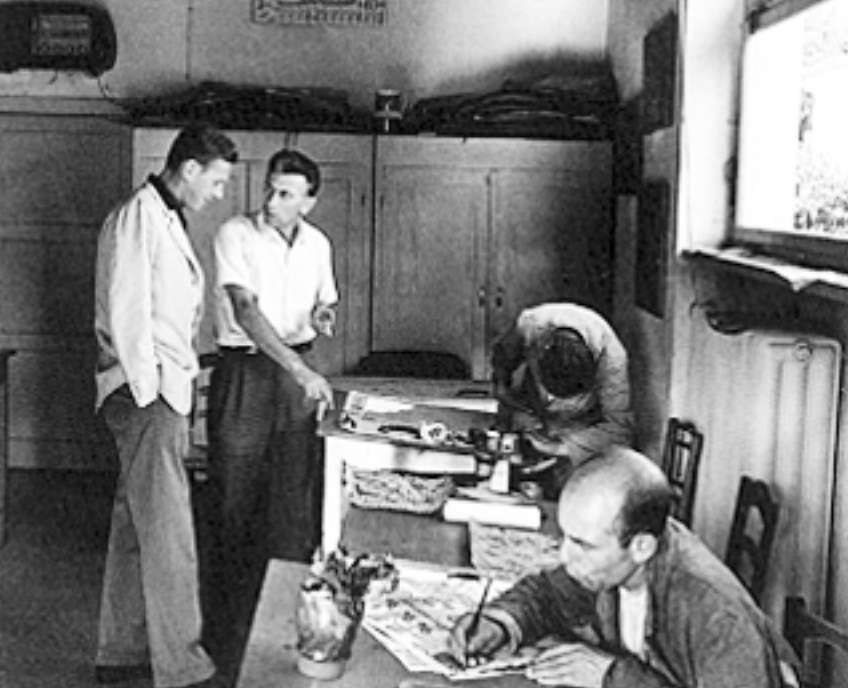

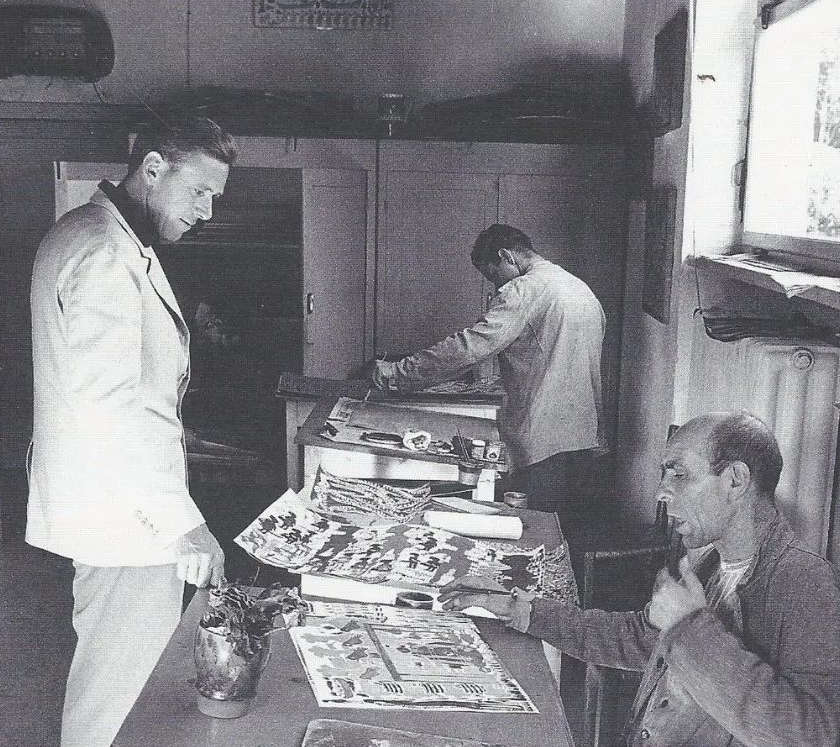

A few years passed before Charles began to express his creative impulses again. Around 1955, with makeshift means, he began carving figures on the walls of the ward or drawing some compositions on the floor with his bare hands, arousing the disapproval of the nurses and attendants. He was even tied up, his psychiatrist recalls, to prevent him from “littering the walls” with his seemingly incomprehensible marks. To solve that unusual problem of dealing with a patient, in the institution’s carpentry shop the doctors set up a table and gave Zinelli paper and brushes, but the real turning point for Carlo and his art came in 1957, when Scottish officer, journalist and sculptor Michael Noble organized a workshop for free graphic and artistic expression in the nursing home, of which Zinelli became a frequent visitor. The painting atelier, in which there was a total absence of impositions on technique or method of work, became a kind of Renaissance-style art workshop, and after the first group exhibition that had brought together a selection of works from St. James, it also attracted the interest of critics and journalists. Noble meanwhile had begun to open the doors of his sumptuous villa on the shores of Lake Garda to patient-artists, as well as a large and diverse community of poets, literati and musicians.

From that moment there followed eighteen years of pure creativity for Carlo Zinelli, which did not fade even after Noble and his wife Ida Borletti left for Ireland in 1964. The artist, as we can call him at this point, painted eight hours a day, filling each sheet with his figures, and when there were none left he would turn the paper over and continue on the back. When one work was finished, Carlo would pick up another sheet and resume drawing. Because painting, Andreoli emphasized, was for him the equivalent of living. Again the psychiatrist recounts that, even in his mental isolation, he would deliver sermons that were incomprehensible but full of meaning and, despite the fact that in his psychotic condition he no longer recognized the meaning of words, he would use the words to compose nursery rhymes full of neologisms and poetic gimmicks.

Sensing the artistic value of Zinelli’s works, Andreoli decided to travel to Paris in 1961 with the hope of meeting Jean Dubuffet and showing him some of his works. The major promoter of Art Brut - who at the time was joined by the Surrealist André Breton, who moreover played a crucial role in convincing Dubuffet about Carlo’s artistic value - then agreed to acquire about ninety works by the Veronese artist, which have since become part of the collection of works by “outsider” artists. Collection that, donated to the city of Lausanne in 1971, made possible the birth of the Collection de l’Art Brut, the museum that still today represents one of the most significant poles for the knowledge and appreciation of art created by inmates in psychiatric institutions and in general by those who did not participate in the “official” art circuits.

Zinelli’s frenetic production lasted until 1970, when the hospital in San Giacomo della Tomba was moved to a new location in Marzana, where a larger and brighter atelier was set up. But for Carlo’s fragile mind, the move was fateful: his rapidity ran out, his imaginative power suffered a crisis, and the leader of the school ceased to lead that incredible movement in which other patients also participated. The artist began to suffer from chronic bronchitis, between 1971 and 1973 he gradually abandoned painting, and the following year it was life that left him.

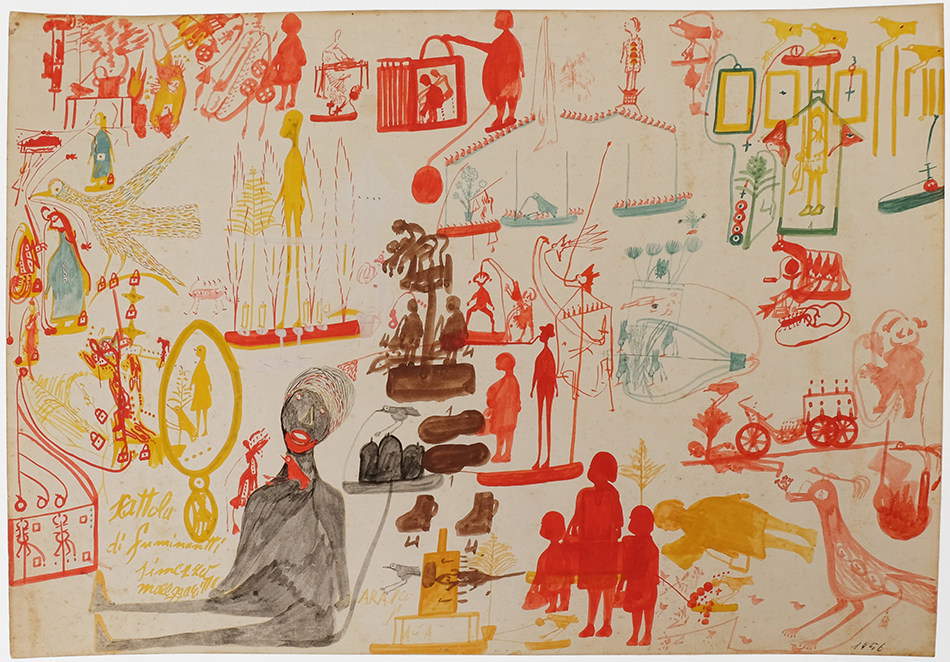

Zinelli’s work, between horror vacui and hypnotic repetition

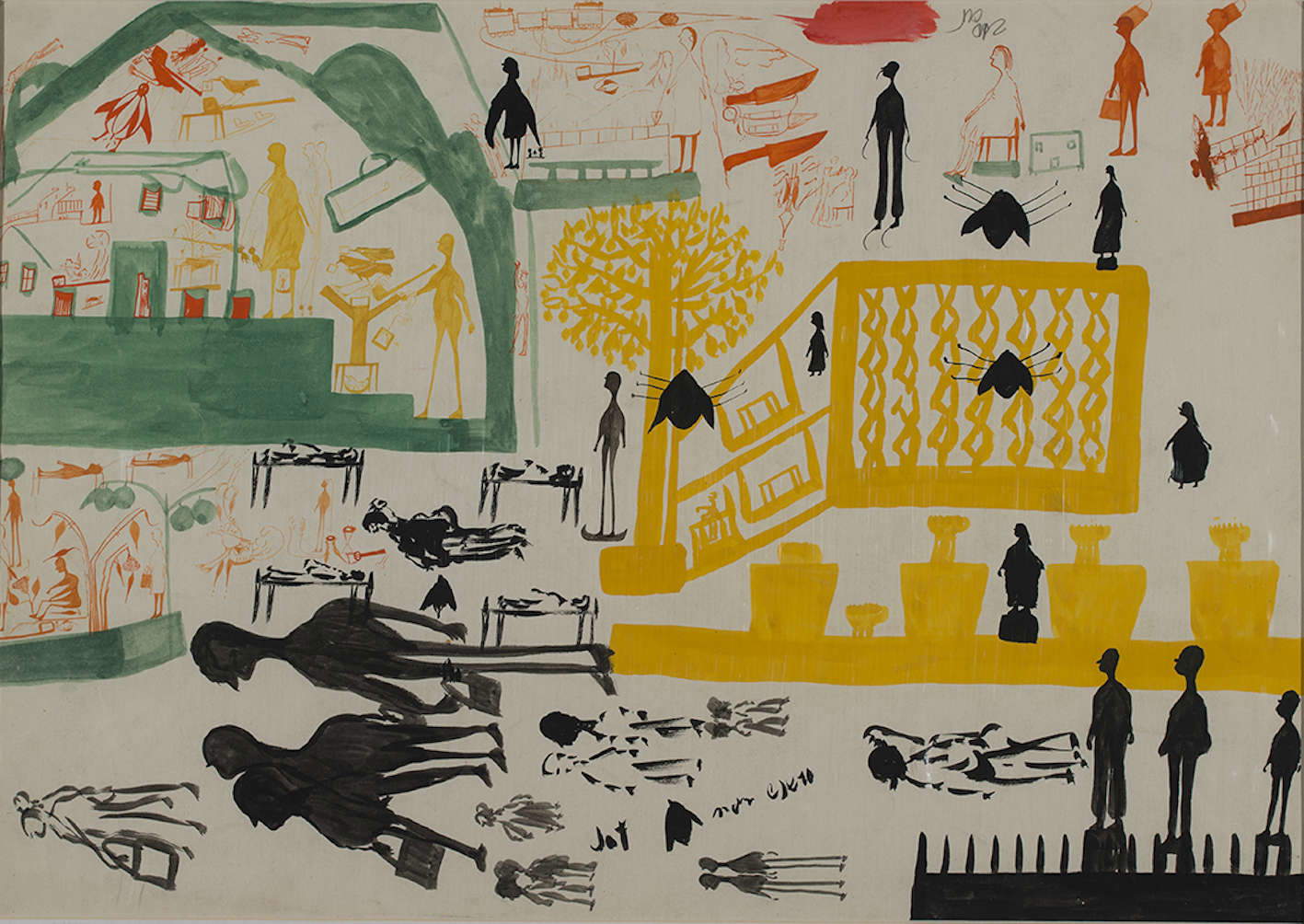

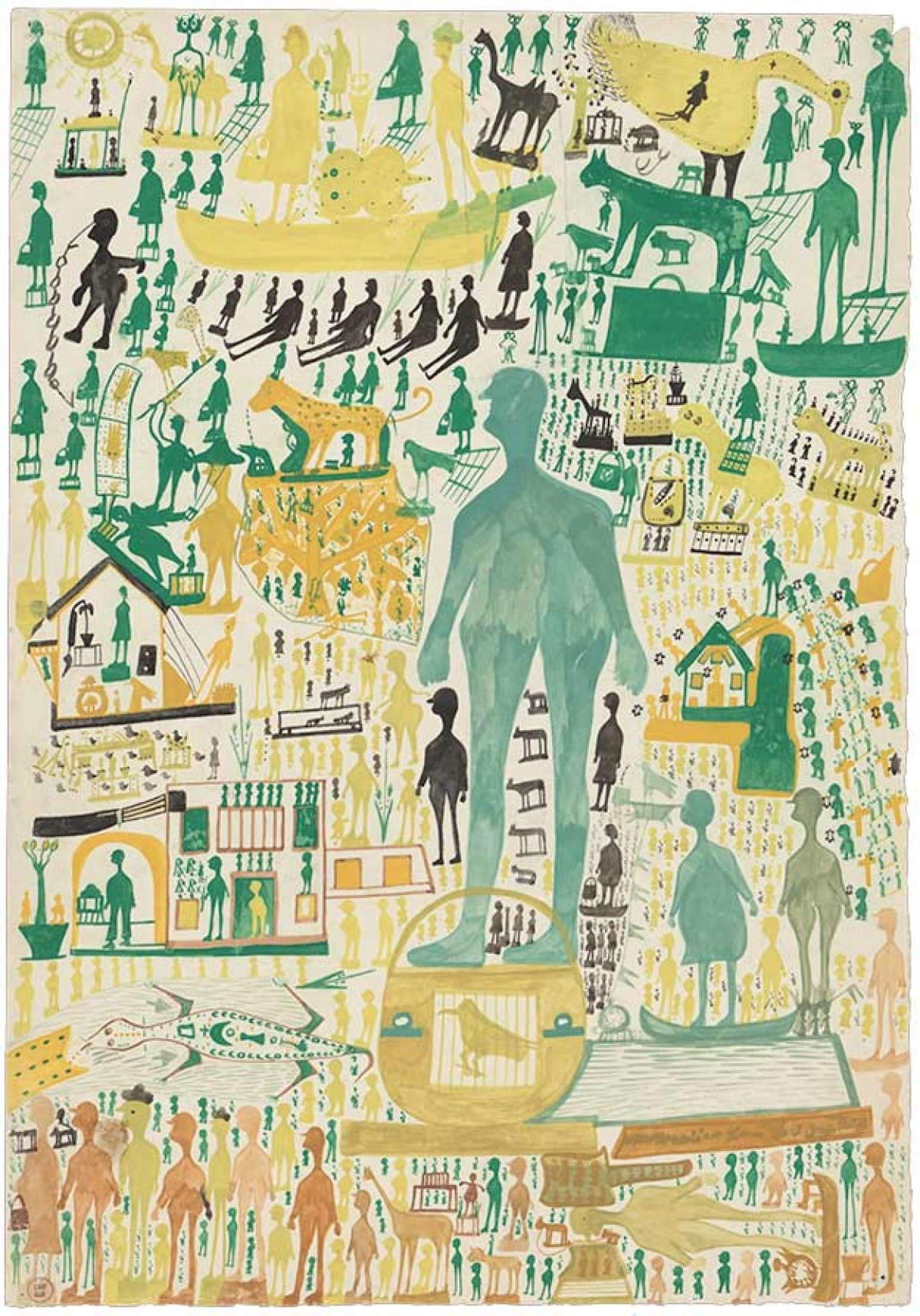

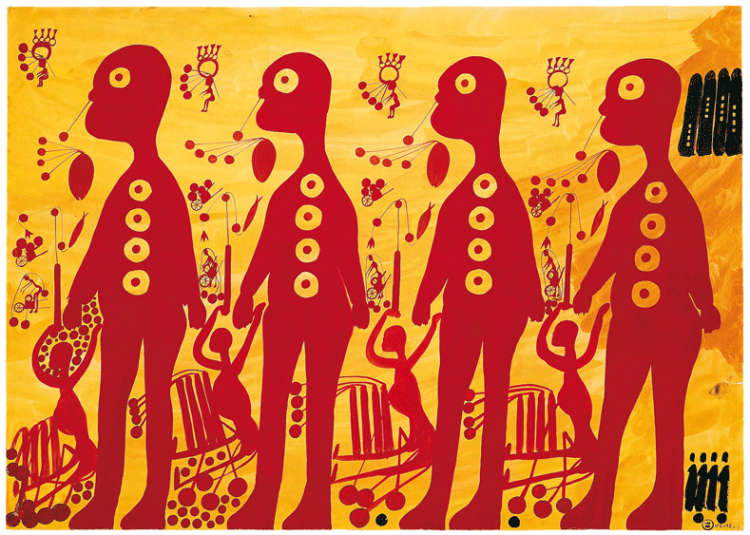

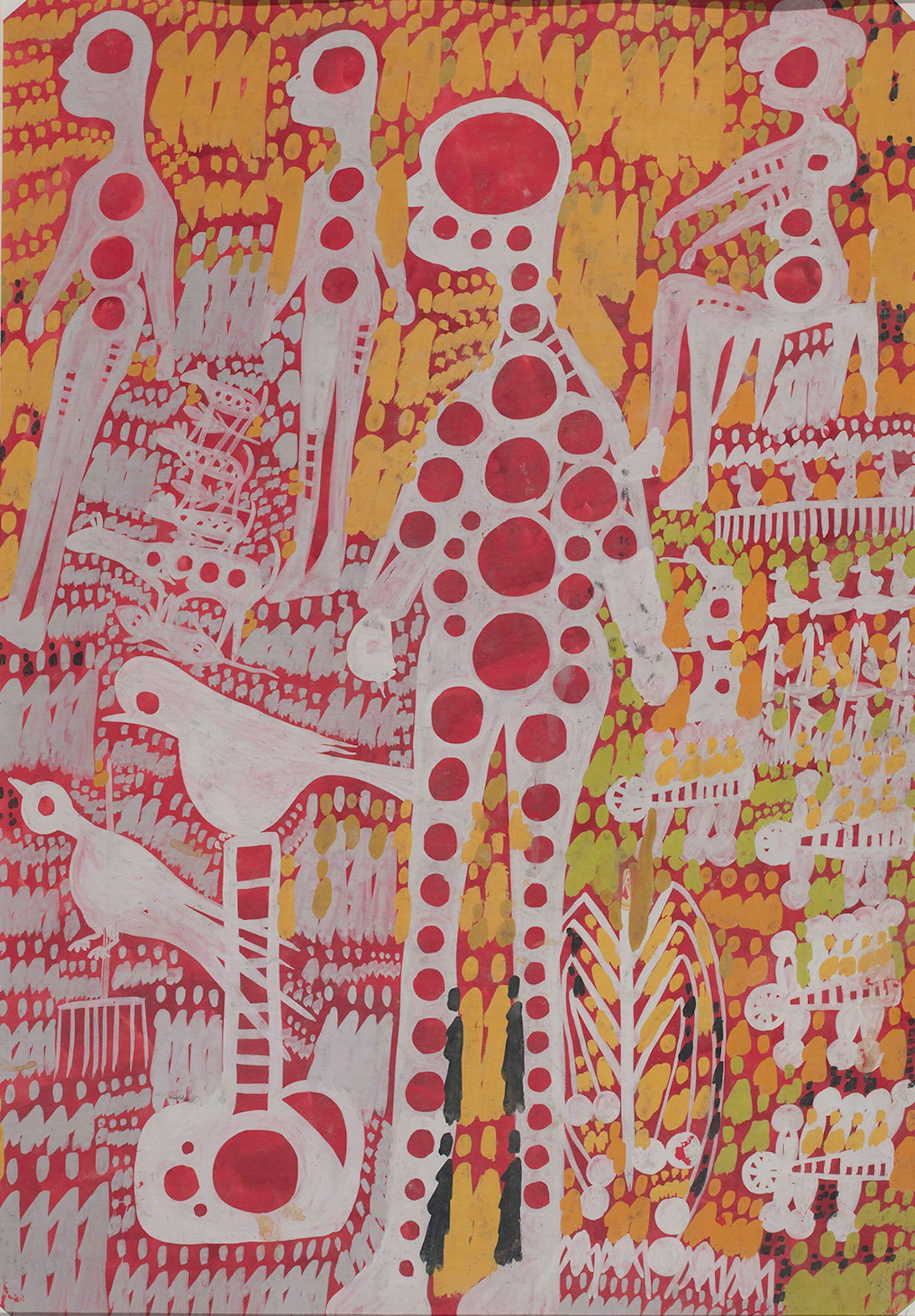

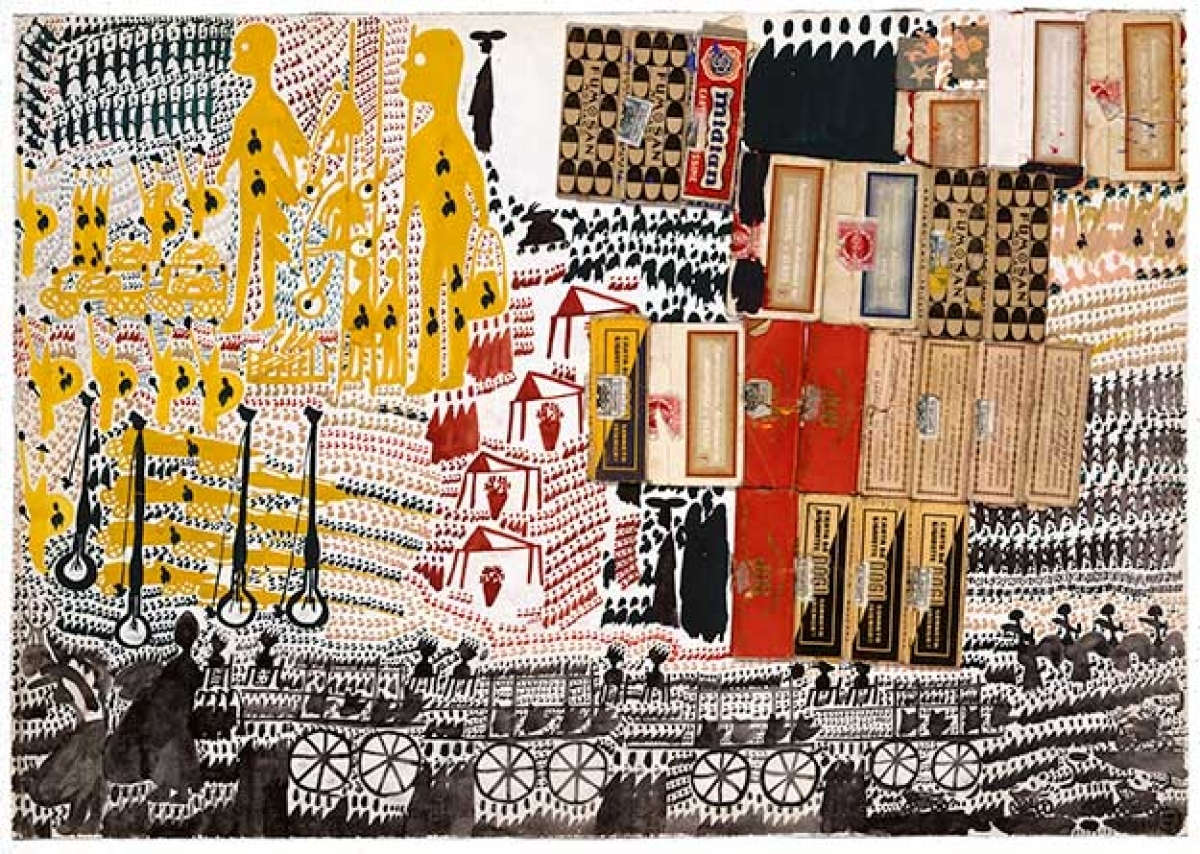

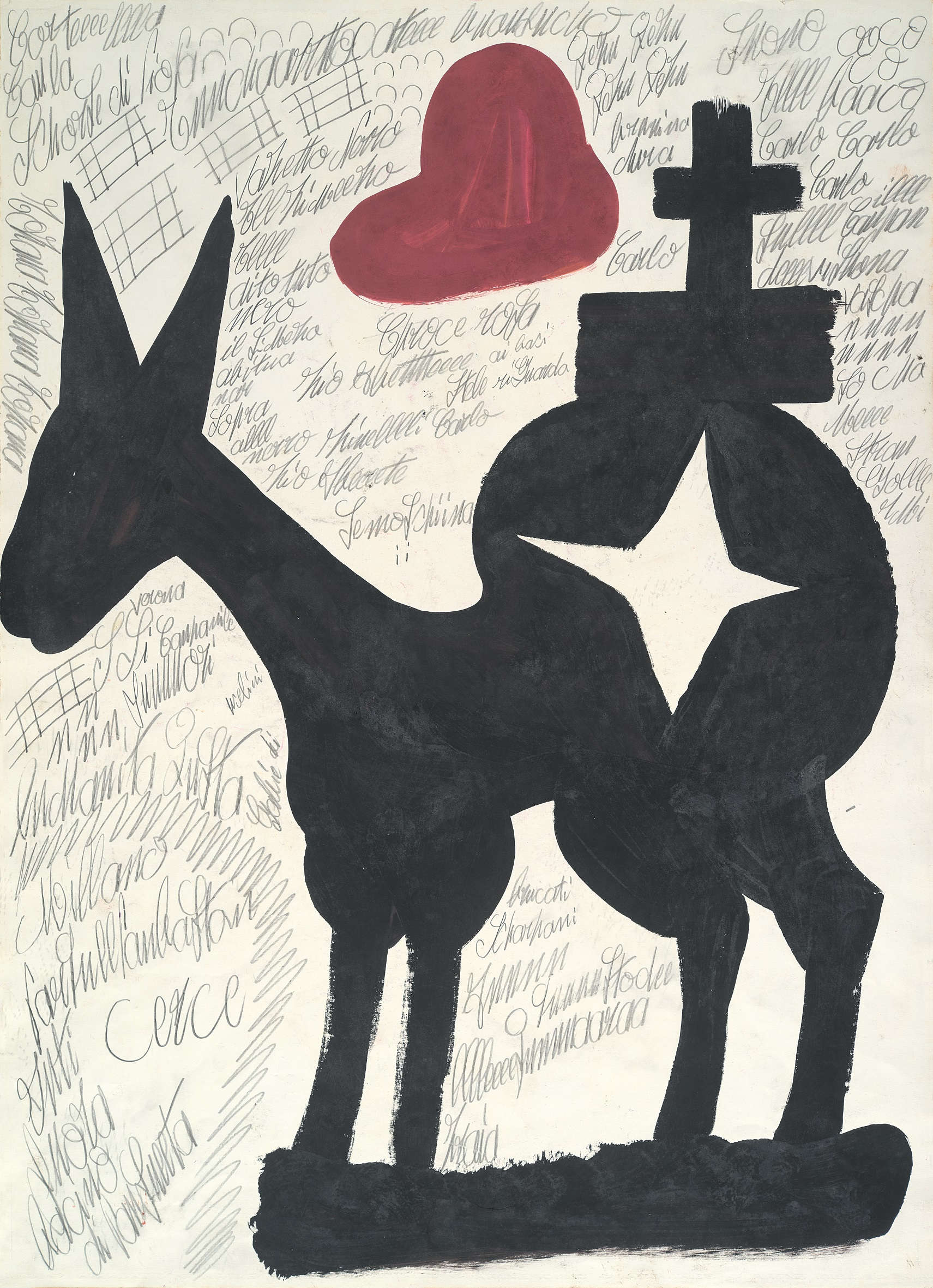

But what are the factors that allowed Zinelli to gain status as an artist and not just be regarded as a schizophrenic who expressed himself through shapes and colors? After an initial period of experimentation and exploration of techniques, Carlo achieved remarkable skill in the composition of the works, which were always crowded with figures but progressively arranged with great balance against backgrounds of overlapping, shaded bands of color and refinely juxtaposed hues.4 The dominant interest in background color faded from about 1966, when black figures on a white background began to prevail.

His favored subjects-often repeated in series of four, as if that number held a “magical” power for him-derived from memories of the peasant environment: animals, such as birds and horses, thus recur, and among the human figures (often “pierced” by white circles) the famous “pretini” stand out, then women with handbags, alpini, characters with hats; stars, boats, wagons, airplanes, crosses, as well as the occasional rifle or cannon are also added. Everything contributes to filling the entire pictorial space, a feature moreover common to other outsider artists, and one thinks for example of August Walla or Oswald Tschirtner, who shares with Charles the synthesis of figures-particularly in his Menschen series-as well as some biographical elements: enlisted in the German army, the Austrian was sent to Stalingrad as a radio operator, then spent a year in a prison camp and began to show signs of mental illness, such that he was interned in the Gugging center. While it may seem forced, it is also suggestive to propose a comparison between Zinelli’s black, hieratic and archaic silhouettes and Alberto Giacometti’s famous elongated and slender sculptures, although the latter cannot be considered an outsider artist; however, it does not seem coincidental that precisely Femme debout by theSwiss artist was chosen as the incipit of the aforementioned exhibition L’arte inquieta because it was considered capable of evoking Giacometti’s reflections on loneliness and the absolute separation between individuals, as well as on the ephemeral volatility of life.

Zinelli also combined drawing with speech in the form of prayers, nursery rhymes, and songs whose calligraphy was gradually transformed into ornamental arabesques, with the letters arranged for decorative purposes. Those familiar with Art Brut cannot help but think in this regard of the work of Federico Saracini, who was interned in the late 19th century at the San Lazzaro psychiatric hospital in Reggio Emilia. There is no lack of further technical experimentation in Carlo’s work: for a time he practiced the technique of collage, while towards the end of the 1960s he combined graphite with colored pencils, and then also used pastels and biro pen. “Carlo’s work tells us of an exhausting relationship with language, living on hypnotic, obsessive repetitions and a body that has its wounds but does not seek new cuts, ”5 summarizes Giorgio Bedoni, another psychiatrist and psychotherapist who was among the curators of both the 2013 Borderline exhibition in Ravenna and the Reggio Emilia project.

From his asylum claustrum Zinelli thus invented his own imaginary fantasy world, densely populated, whose figures represented perhaps the last subtle link between his mind now hopelessly separated from the world - and remember that the term schizophrenia comes from the Greek schízō (’I divide’) and phrḗn (’mind’) - and the reality that surrounded him. So much so that Vittorio Andreoli said that “even the most closed schizophrenic is so human that he can speak through the most surprising language: art. ”6

Notes

1 Carlo Zinelli. General catalog, edited by Vittorino Andreoli and Sergio Marinelli, Marsilio, Venice, 2000.

2 Carlo Zinelli, ad vocem, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 100, 2020, www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/carlo-zinelli_(Dictionary-Biographical).

3 Vittorino Andreoli, Carlo and his psychiatrist, in Carlo Zinelli. General Catalogue, op. cit., p. XV.

4 For a complete stylistic analysis of Zinelli’s work, see Flavia Pesci’s contribution, Carlo Pittore, in Carlo Zinelli. General Catalogue, op. cit., pp. XXXVII-XLV.

5 Giorgio Bedoni, Borderland. The Moving Frontiers of the Imaginary, catalog of the exhibition Borderline. Artists between normality and madness, edited by Giorgio Bedoni, Gabriele Mazzotta, Claudio Spadoni, Ravenna, February 17-June 16, 2013, pp. 27-28.

6 Andreoli, op. cit., p. XXVI.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.