"Making art is an arrangement that involves every aspect of life." Conversation with Cesare Biratoni

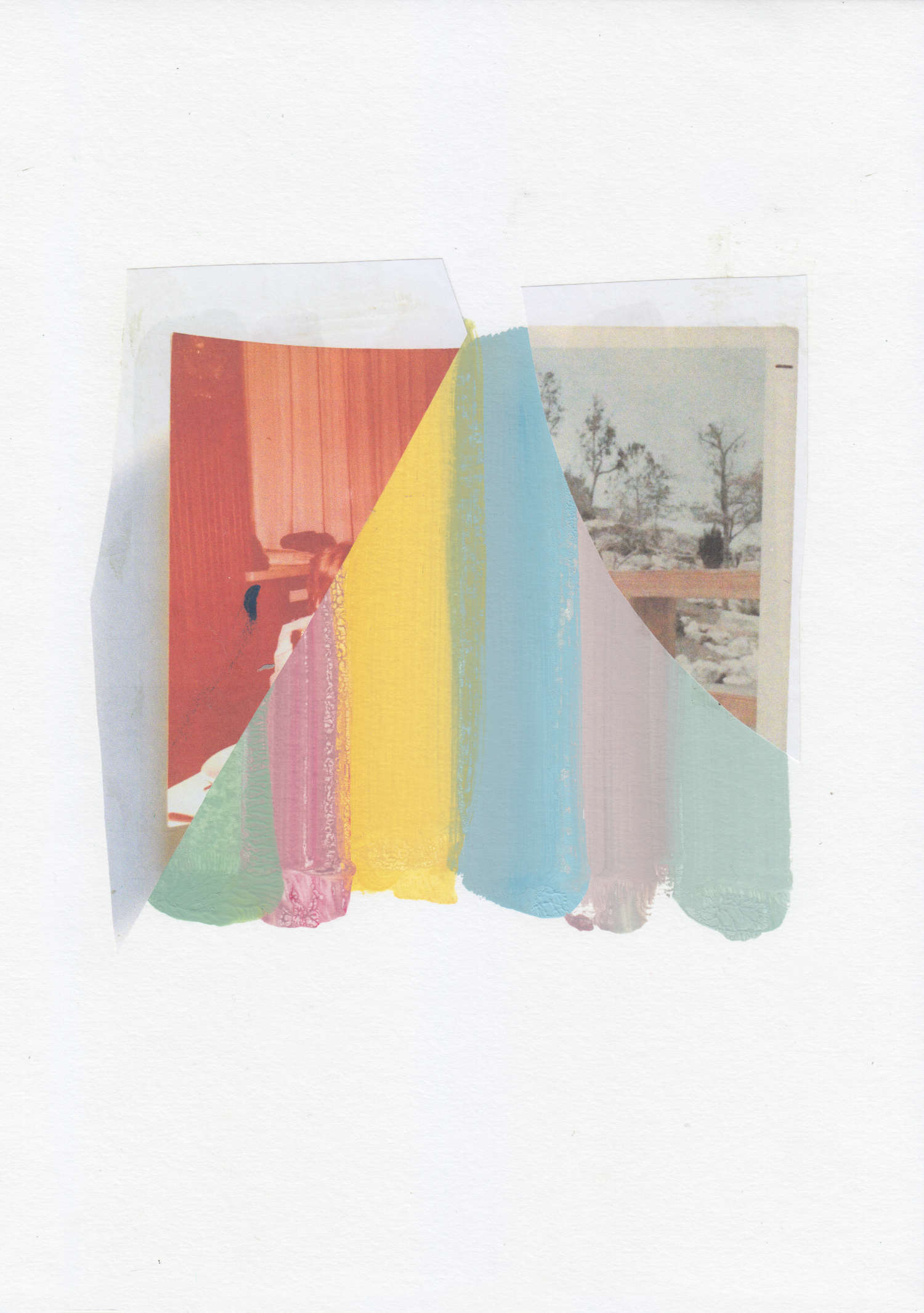

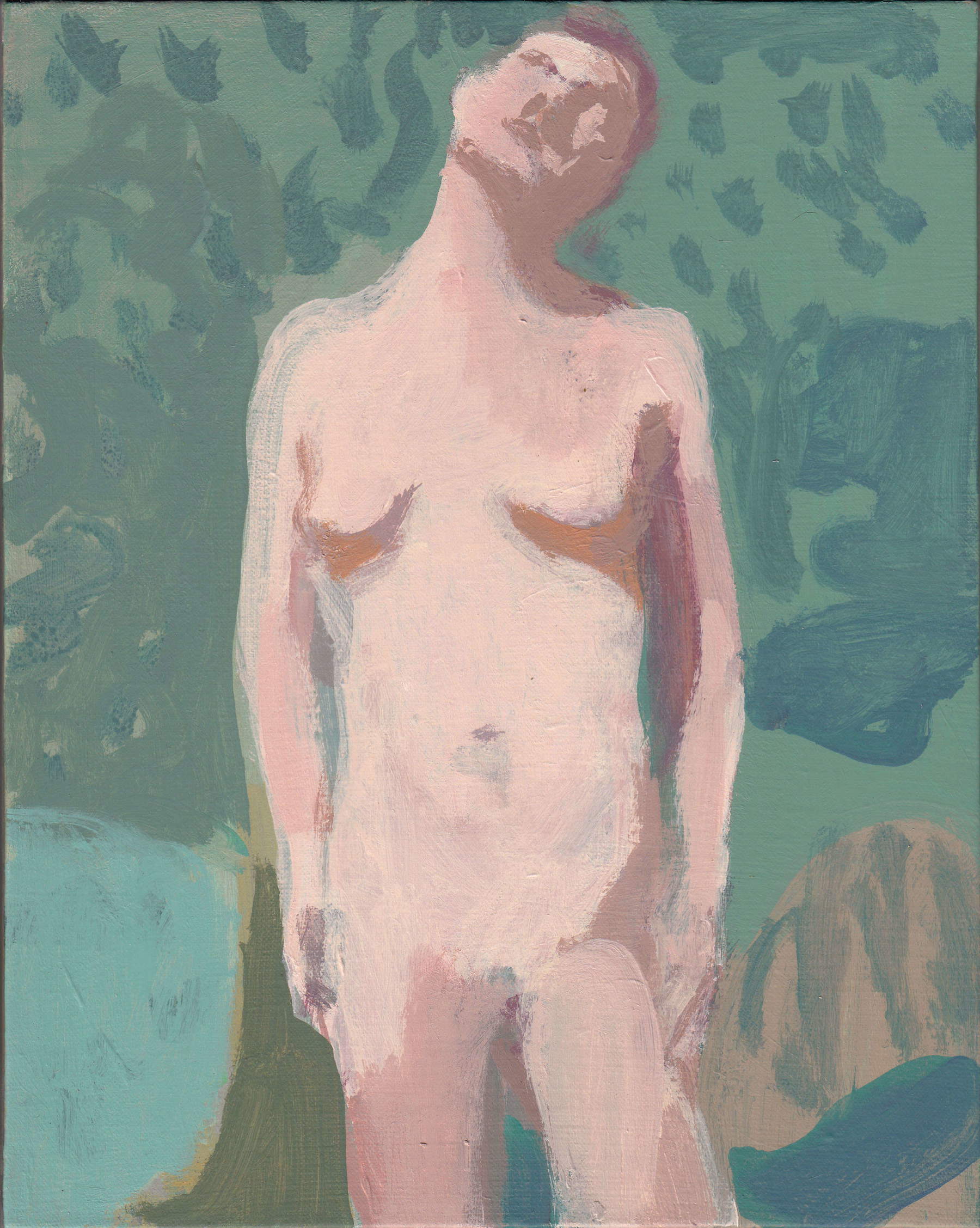

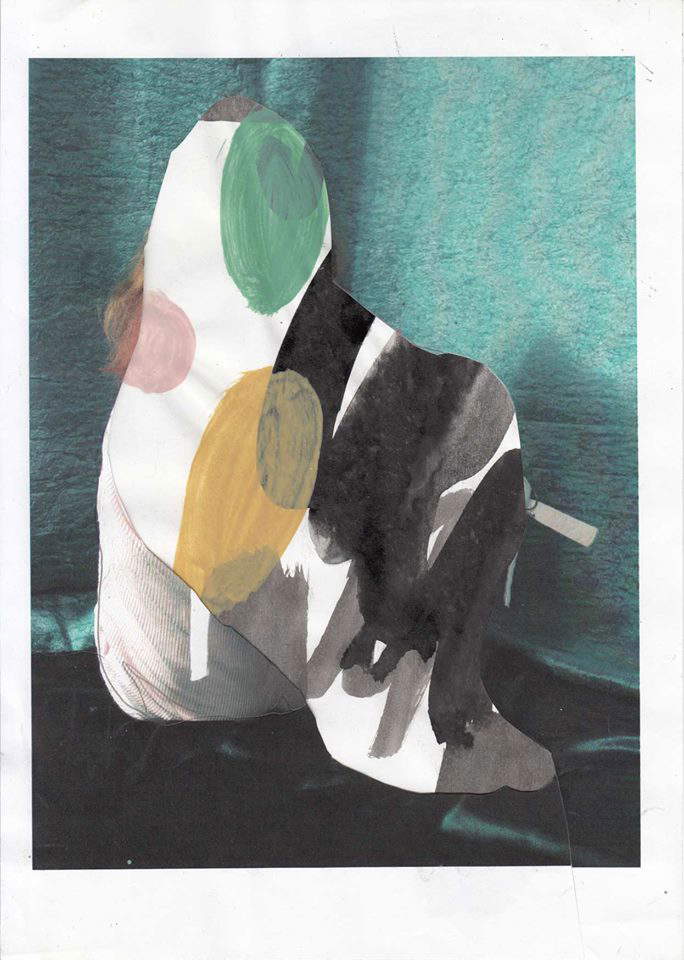

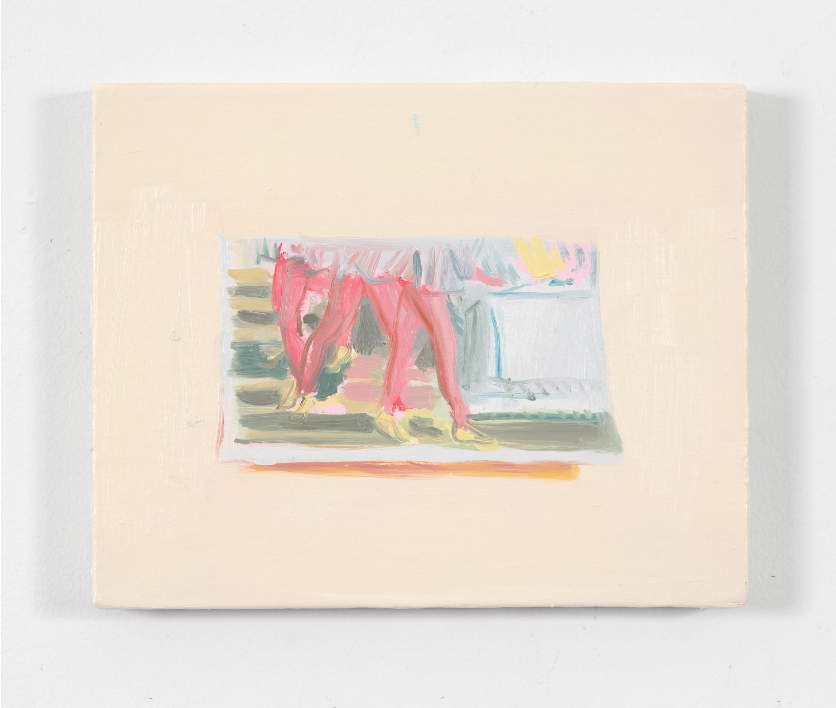

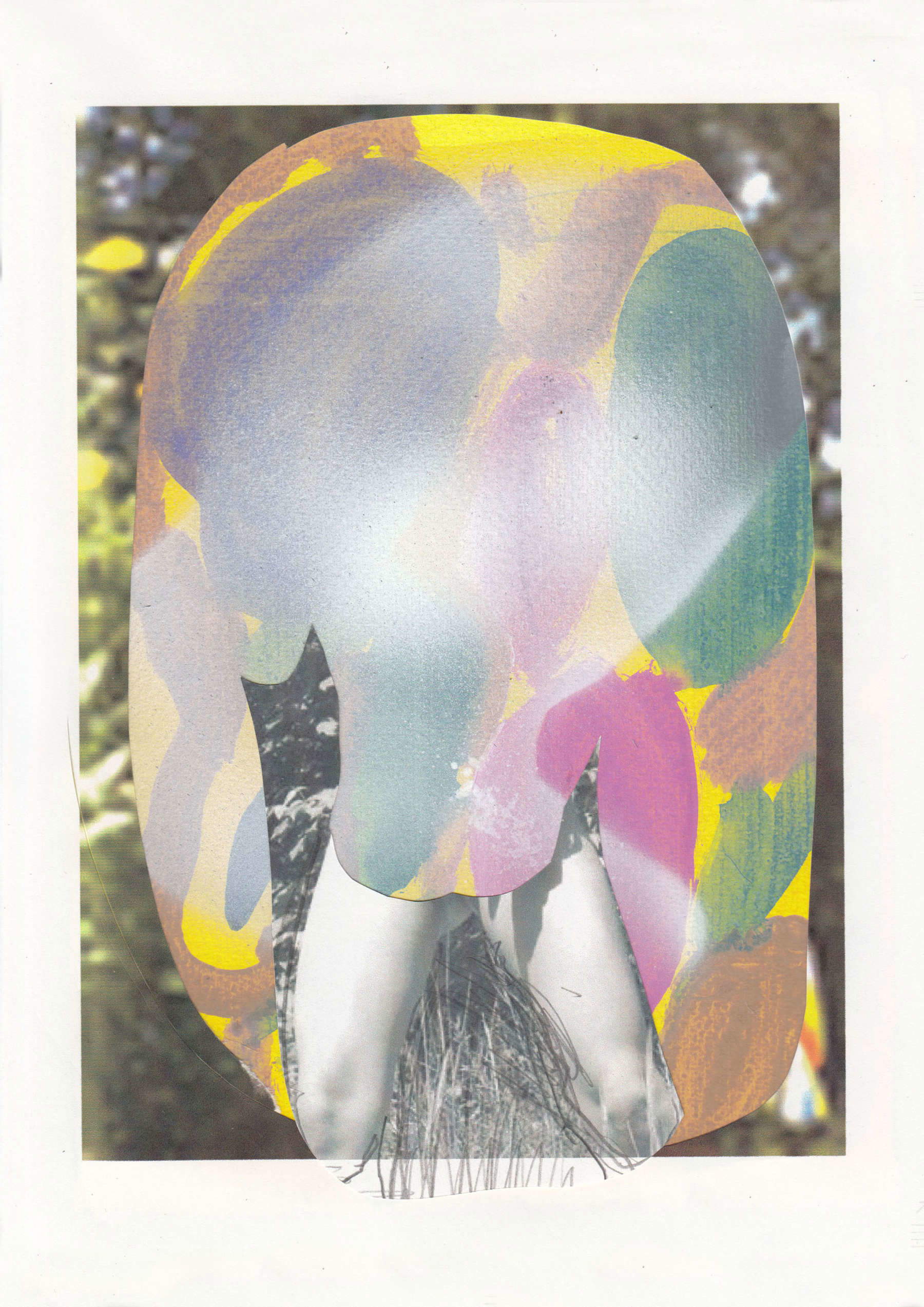

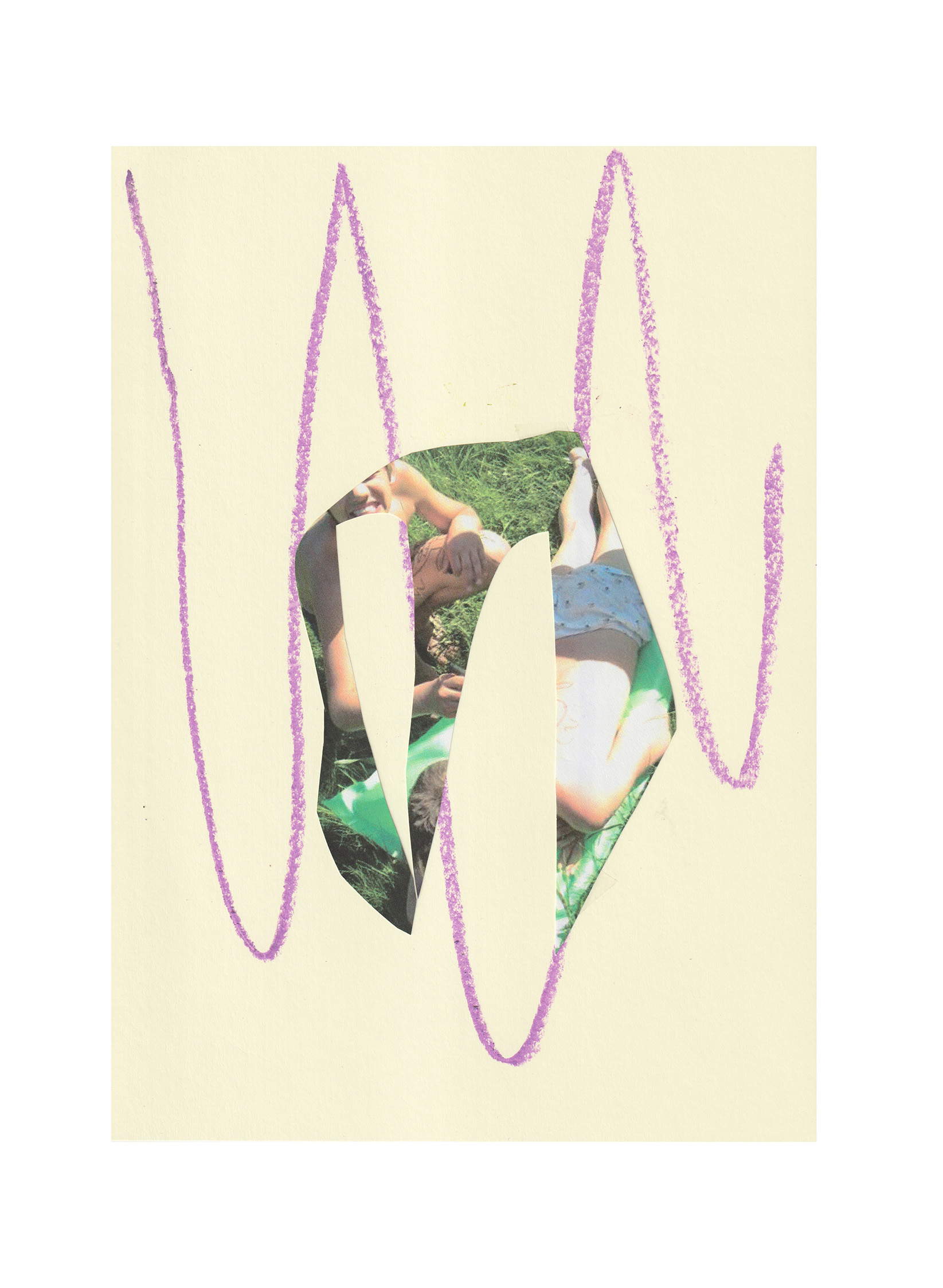

Cesare Biratoni, born in Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto in 1969, resides and works in Busto Arsizio. In his work, there is no distinction between collage and painting, nor between drawing and manipulated and recomposed photography. Biratoni is distinguished by his pictorial works filled with tension and making use of different materials, with recurring themes such as sedimentation and the daily repetition of the gaze on the surface of the work. According to Biratoni, the concept of “work” seems to be linked to the possibility of the painting being observed by others, gazes that do not understand the sense of destruction operated at the beginning of the creative process. To compensate for this disruption, the artist uses historical subjects such as the painter and the model, the bathers or the painter alone, trying to pose them on surfaces that are as resolved, flat and clipped as possible, even though they are the unfinished result of a series of collisions that echo beneath the surface of the work. In this conversation with Gabriele Landi, Biratoni talks about his art.

GL. Cesare, in doing interviews with artists, and being an artist myself, I realized that if you want to talk about a work in more depth, it is necessary to make a premise by asking the interviewee to tell, for example, if during his childhood he witnessed, in an unconscious way, the manifestation of the first “symptoms” of his predisposition to art...

CB. Gabriele, I like that you call them “symptoms,” because you seem to give them a clinical meaning. In fact it was a bit like that; as a child I was attracted to images. I used to keep my eyes fixed on the illustrations in books and strive to see if there was something behind them; I saw a thickness, a material vibration. They were images, shapes and colors that referred me to something else from them. So if I had to decide what were the first symptoms of this predisposition or obsession, then I would answer that it was a disposition to fixity of gaze, to the attempt of sight to restore life and body to the images that fascinated me most.

So art has a “magical” power for you?

I don’t know, I use that word very little. If by magical you mean something that is transformed into something else then I guess you could say in part yes. But maybe thinking back to those fixities I was telling you about it’s more about desire.

What kind of desire are you talkingabout-erotic?

The desire to own, understand, and be about the images. The need to look at them, to draw on them, to copy them, to understand how they are made.

What studies did you do and what were the important encounters you had during your formative years?

I studied at Brera with Beppe Devalle, which was certainly an important encounter. In his classroom you drew a lot with a more mental approach than in other schools of painting, of conceptual reflection on the medium. At that time in the academy you could go to hear a lecture by Fabbro or take the aesthetics course with Leonetti, enroll in pedagogy and then find out that the course was taught by Sanesi who instead read William Blake in English. Then over the years the important encounters, and consequently the stimuli, were many; artist friends, school colleagues, and even exhibitions; one among them, the anthological exhibition on Seurat at the Grand Palais in Paris in 1991.

What struck you about Seurat’s work?

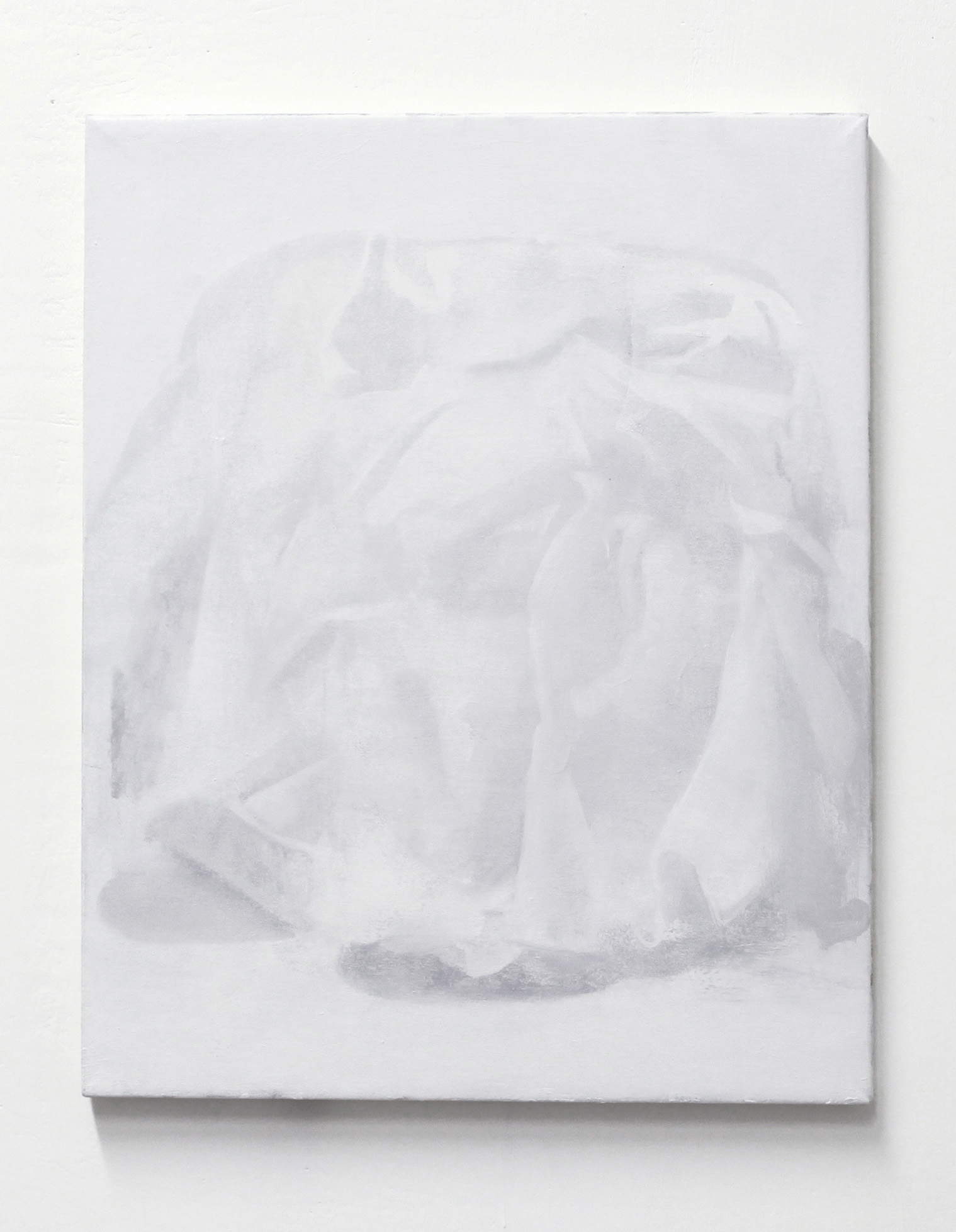

Especially the small preparatory drawings made with Conté pencil. I really liked the fact that before arriving at that composition of colors juxtaposed with meticulous lightness and patience there was that study of light, volumes ... but above all the luminous dust that envelops the forms creating a kind of fog between the viewer and the subject. I was then intrigued by how in the end the paintings, despite the use of color, from a certain distance appeared as if enveloped in a mother-of-pearl grayness. Somehow a return to the small drawings, but with all the colors inside.

Cesare Biratoni, Still Life

Cesare Biratoni, Still Life Cesare Biratoni,

Cesare Biratoni, Cesare Biratoni,

Cesare Biratoni,

Cesare Biratoni,

Cesare Biratoni, Cesare Biratoni,

Cesare Biratoni,

Is it from this encounter with Seurat’s work that your works on bathers originate?

I think so. It is a recurring theme in my work.

In your work you often resort to photography, which you combine with painting. Are the photos made by you or do you retrieve them from other sources?

My sources are heterogeneous; I started by cutting out images I used to print myself that served as a subject or part of a subject for painting. Then I started taking photographs and also, in some cases, myself. The fascination with photography I think can be inferred from the way I work. I think of it as iconographic material, with all the implications, most of the time unintentional, that it carries ... but also, in some cases, palette, form and mark. There is a point, or at least I think there is, at which photography stops being “just” photography, just as matter, at a given instant, stops being “just” matter and becomes form, painting, or something else.

The material that you collect and employ in your works accumulates stratifies until it loses its recognizability and as if you put it under a process of slow transformation. When you work, is it the various pieces you assemble and paint that suggest their placement to you or do they obey a specific design intention of yours?

Both. There are vague patterns that I have in my mind, that I imagine first ... then in the most intense phase of the work, as I think anyone who is involved in this kind of activity knows, suggestions, suggestions, images overlap; it is as if despite the fact that there has been an attempt to design, at that specific moment, just as things are forming, you lose what seemed to be a definite will, and that, as you say, it is things that suggest solutions, paths and results even very different if not opposite to the initial premises.

When you work do you leave room for chance?

I’m pretty sure that the preparation and conditions you build around the work also serve to foster a certain amount of chance. In my case, the encounter between different things -- painted papers, photographs, prints or whatever -- happens most of the time in a random way.

Brancusi said that the most difficult thing is not to make things but to put oneself in the state to be able to make them: how does this happen for you?

Separating the disposition to do from the doing itself is almost impossible for me. When I think of things to do, imagine them, reason about them and dispose myself to produce them, it is as if I am already working. I happen to feel very close to the work and to imagine extraordinary developments of it the moment I leave the studio and walk home; that is for me a moment of absolute freedom released from the need for contingent fulfillment.

Cesare Biratoni,

Cesare Biratoni, Cesare Biratoni,

Cesare Biratoni, Cesare Biratoni,

Cesare Biratoni, Cesare Biratoni,

Cesare Biratoni, Cesare Biratoni,

Cesare Biratoni, Cesare Biratoni,

Cesare Biratoni,Do you find yourself changing a work even after a long time?

Yes, especially with painting, because there are things that are stationary, unresolved, even for years in the studio.

Does the idea of work that is precarious, provisional, open to possibility and modification appeal to you?

I think there is a point at which the work is defined. But before we figure out how and when -- yes, the whole thing is open and modifiable. But it is also true that at some point you have to close the process. I don’t see impermanence as a value--the fascination with the unresolved. I cannot associate the substance of certain materials that I use...for example, paper, with an idea of precariousness. If anything, the problem, certainly no small one, should be that of preservation and durability of the work.

Is it because of this instinct of preservation that you sometimes paint on canvas simulating with paint what you do with paper?

I don’t seem to do that; I see them as two completely different processes. There might be similarities, but only from a compositional point of view. The problem of preservation arises especially with paper; we know how little it lasts and how it deteriorates over time, but it doesn’t bother me that much, I’ve seen some collages from the 1970s and 1980s where the scotch tape, for example, has completely yellowed and this gave the work an aura, a kind of patina of time that I liked.

What importance do you attach to drawing in your work?

I have always thought that drawing and cutting out are two very similar processes. I also think that painting also has to do with drawing. I find it hard not to think about drawing every time I try to make something; Degas said that drawing is not the form, it is the way of seeing the form.

Matisse also had a similar approach, he put drawing on the same level with cutout, which in his case came close to sculpture. Are you also interested in the third dimension, in a spatial approach?

I am very interested, especially in recent periods, in the thickness of things. I find that there is a correspondence between composition, weight and thickness. However, I’ve always let the layers of my collages have a certain mobility, that they cast a slight shadow on the plane.... a bit like the still lifes of photos that I’ve been trying to paint for quite some time. So maybe yes, I am interested in the third dimension. The thickness of the layering I think is also related to time; I like that you can “see” it.

I take this opportunity to ask you to go deeper into the question of time, which seems to me to be one of the foundations of your work.

It depends on what you mean by time. There was a question related to memory ... but I haven’t given much importance to this issue for years, that I don’t consider it in the sense of archiving, collecting. I like to accumulate clippings, photos, papers, this yes; but without real archival rigor, or even philological rigor, in fact I mix family photos with found images and colored papers or sheets, recycled and more. When I paint images my intent is always and only pictorial. I think you can tell by the fact that I tend very often to erase, to go over other layers of color on the image: it seems to me that when the photo, or the subject is too well done, described, something is lost. More than the dimension of time (in the sense of memory), for example in still life photos, I am intrigued by the photo itself. To quote a fine definition by Fontcuberta: “... photography, before being a document relative to reality, is a document relative to its own ambiguous nature.”

Cesare Biratoni, Still Life

Cesare Biratoni, Still Life Cesare Biratoni,

Cesare Biratoni,

Do you happen to take photographs with the intention of using them for artistic purposes, or instead are they simply photos that fortuitously find their place in your work?

The second aspect you say prevails, because I enjoy and enjoy the search for sources. I have also taken (bad) photographs that have served me, especially to compose collages or paintings where the subject is myself, not so much as a portrait but as a character painting.

In a previous conversation you told me about your stateless status which seems to me to connect somewhat with the idea of ambiguous nature. Are art and life intimately connected in your work ?

I think it is for anyone involved in art; it is difficult to be a “technician” of art. The notion of professionalism, for example, is very far from me; I try and try again, mix things and then see what happens. That is why I believe that making art is an arrangement that involves every aspect of the practitioner’s life.

Are you interested in the dimension of poetry?

I am very interested in it. For me art and poetry are closely related; in both cases it doesn’t matter (not primarily at least) what you describe or tell but the form by which you come to define something from something else. I don’t see much difference between any course for aspiring poets and a painting (or visual arts) course in a fine arts academy.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.