Lost in antiquity is the origin of the nickname by which the Madonna with the Long Neck, the masterpiece by Parmigianino (Francesco Mazzola; Parma, 1503 - Casalmaggiore, 1540), now housed in the Uffizi, is known today. The work is known thus ab antiquo: suffice it to say that already Luigi Lanzi, in his Storia pittorica dell’Italia written between 1792 and 1809, said that according to some the work was excessive because of its “proportions that were too long and in the stature, and in the fingers, and in the neck,” and that “from this defect it is commonly called ’of the long neck.’” Its main and most obvious distinguishing feature, theelongation of proportions, was formerly seen as a flaw, as breaking the balance, a grace so refined and sophisticated as to be disproportionate. Yet therein lies Parmigianino’soriginality and greatness : his break with Renaissance harmonies was intentional, to show that that balance was not the only possible attitude toward the sacred (and life in general).

Everything in this painting is deliberately exaggerated. The Virgin’s extraordinarily long neck is not the only feature that immediately jumps out at the viewer’s eye. The very long fingers of her tapering hand are perhaps even stranger. And what about the Child, also too long and too big to be an infant? He almost seems, then, to be slipping from his mother’s womb. But the eye is also inevitably drawn to the ivory nudity of the angel’s leg on the left, as solid and towering as the tall marble column we see on the right, and which seems almost a quotation of the John the Baptist who appears in Correggio’s Madonna di San Giorgio . And why then gather so many angels into such a narrow and crowded space as the one we see on the left? If there is madness in this, wrote a great art historian like Ernst Gombrich, then “in this madness there is method.” “I can well imagine,” says Gombrich, “that some might find the Madonna almost offensive because of the affectation and refinement with which a sacred object is treated. There is nothing in this painting of the ease and simplicity with which Raphael had treated that ancient theme. [...] Yet there is no doubt that the artist achieved this effect neither from ignorance nor from indifference. [...] The painter wanted to be unorthodox. He wanted to show that the classical solution of perfect harmony is not the only conceivable solution; that natural simplicity is one way to achieve beauty, but that there are less direct ways to achieve effects that are interesting to sophisticated art lovers. Whether we like the path he took or not, we must admit that he was consistent. Indeed, Parmigianino and all the artists of his time who deliberately tried to create something new and unexpected, even at the expense of the ’natural’ beauty established by the great masters, were perhaps the first ’modern’ artists.” In the painting, the Virgin appears under a pink curtain, pulled to the left of the relative to show the slender figure of the Virgin, painted along the entire vertical axis of the panel, with her feet resting on two cushions, seated perhaps on a throne that we do not see (and by removing this spatial reference, Parmigianino further breaks the harmony). She is smiling as she looks down at the Child she holds with her left hand, in a completely precarious position, almost as if she is about to fall. The draperies, transparent, allow a glimpse of her body: we see her navel, her nipple. On the left, here instead are the six angels: one, in profile, the only one with wings, is carrying a vase with a cross. Another, further back, has female features, and is closely reminiscent ofAntea, the Parmigianino work preserved at the Capodimonte Museum in Naples. Max DvoÅ™ák had compared them to six ephebes. Everything is light, transparent, delicate, intellectual, extravagant, ambiguous, conspicuously and proudly anticlassical, contrary to the laws of nature. Everything almost suggests “a pagan cult of beauty,” Arnold Hauser has written.

We know the early history of this modern masterpiece: the Madonna with the Long Neck was commissioned from Parmigianino in 1534 by a woman named Elena Baiardo Tagliaferri, about whom we do not have much information. We do know that she was the sister of Cavalier Francesco Baiardo, Parmigianino’s only known patron at this period of his career, and she was the widow of a certain Francesco Tagliaferri, the owner of a chapel in the church of Santa Maria dei Servi in Parma (a detail, the latter, which allows us to imagine that Elena was a decidedly wealthy woman). And this was precisely the church for which the work now in the Uffizi was destined: a document dated December 23, 1534 includes an agreement with a friend of Parmigianino’s, Damiano de Pleta, in order to prepare the chapel to accommodate an “anconam fiendam per ipsum dominum Franciscum Mazolum,” or an “altarpiece to be made by Signor Francesco Mazzola.” The document also sets a deadline for the completion of the altarpiece, namely Pentecost of the following year, and refers to a payment of 33 scudi already received by the artist in advance for expenses (so there must have been an earlier agreement, which, however, has not reached us): Parmigianino, in case of default, undertook to return the sum already received against a mortgage on his house in Borgo delle Assi in Parma. This was an exceedingly excessive guarantee for the sum paid, and it was therefore imagined that Parmigianino had previous debts with the family: it should be remembered, for example, that Cavalier Baiardo, together with Damiano de Pleta, had acted as surety for the artist in the context of the undertaking of the decoration of Santa Maria della Steccata, for which Parmigianino had been paid 200 scudi in advance. The knight and the architect undertook to pay out of their own pockets for any shortcomings of the painter, and since we know that Francesco Baiardo’s inventory, drawn up after his death in 1561, included 22 paintings by Parmigianino out of 51 total, and 495 drawings by the artist, we can imagine that some of the artist’s property must have come to Baiardo as a result of the complicated contracts the artist had signed.

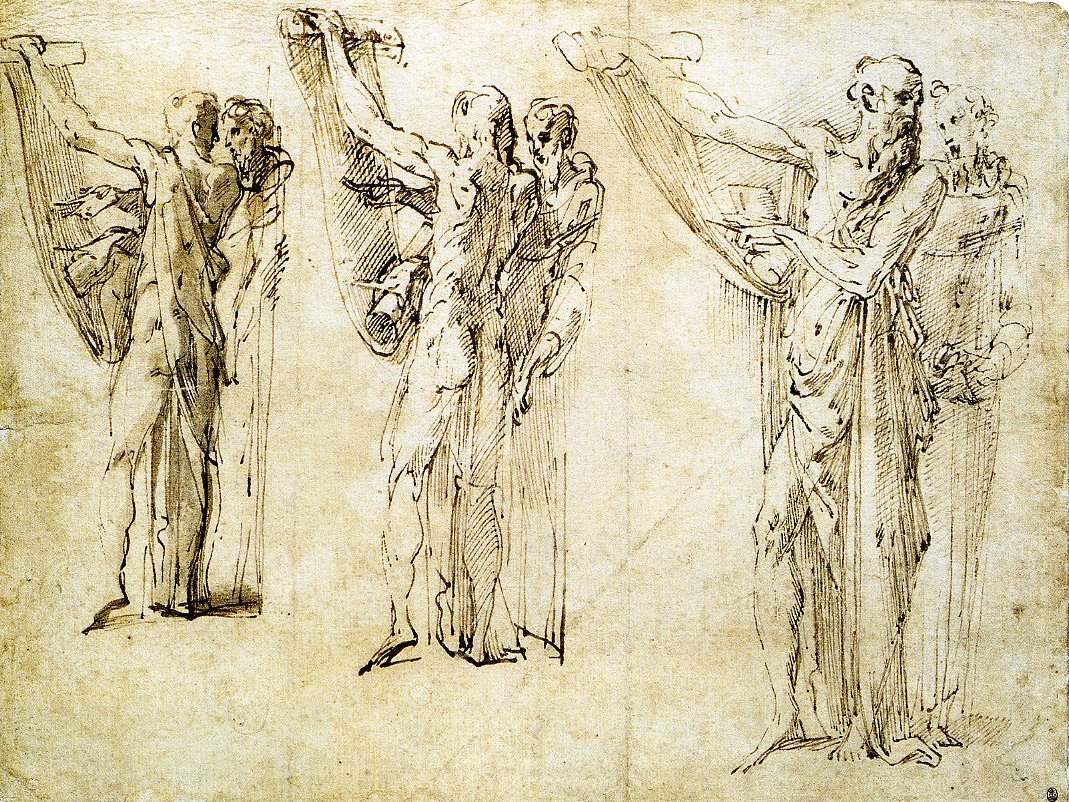

It was Francesco Tagliaferri, in his will, dated October 19, 1529, who had expressed his wish to have an altarpiece executed for his chapel; Elena, therefore, took steps to carry out her husband’s wishes. We are left with several preparatory drawings that show how the artist had to change his mind about the composition several times. In the earliest sheets, we see a composition larger than the present one, similar to the youthful Mystical Marriage of St. Catherine of Bardi, with the Virgin and Child enthroned together with Saints Francis and Jerome (the former was the eponymous saint of the chapel’s owner, Elena’s husband Baiardo Tagliaferri, while the latter was to pay homage perhaps to a brother of Francesco Tagliaferri). In the early compositions, Parmigianino kept to rather conventional patterns, but the detail of the Virgin’s long neck , slightly turned, is already discernible from the earliest ideas. Some drawings, moreover, show an advanced degree of finesse, so much so that they were thought to have been executed to be shown to patrons, but in fact “too little is known,” explained David Ekserdjian, “about the ways in which artists presented their ideas to potential or actual patrons, so there’there is a degree of uncertainty about whether these sheets were habitually highly finished,” although it is clear that, for an accomplished drawing such as the one now in the British Museum, there must have previously been “a certain, unspecified number of more schematic attempts to establish the composition.” There are indeed some drawings left, closer to the Madonna of the Long Neck that we see today in the Uffizi, and thus later than the British drawing, which are traced quickly, with pen, and can therefore be interpreted as pure ideas of the artist, which were solely for his use and were not to be presented to his patrons.

Parmigianino changed his mind several times, as mentioned, even on the iconography. Initially the Child was to be seated on the Virgin’s lap. Then the artist also thought of a Madonna of milk (in some drawings Mary’s robe can be seen pulled aside to show her breasts), and finally he arrived at the solution of depicting the Child lying and asleep, a prefiguration of piety. As for the angels, at first Parmigianino imagined only one, the one who presents the large vase to the Virgin, holding it with his fingertips, and then he arrived at the final solution involving the group we see today on the left, and the saints Francis and Jerome themselves were gradually reduced in scale until they became the two tiny figures (only one of which is completed, that of St. Jerome: of Saint Francis, in the painting, we in fact see only a foot) that appear in the lower right corner. This is, in any case, unprecedented: never before the Madonna with the Long Neck had the saints in an altarpiece been depicted in such minute proportions (and in some preparatory drawings we even see St. Jerome turned with his back turned). The composition itself, so strongly asymmetrical, represented a novelty. “One can find in it,” Hauser wrote, “the Red’s legacy of oddities, the more elongated forms, the slimmer bodies, the longer legs and thinner hands, the more delicate woman’s face and the most exquisitely shaped neck, and the most irrational juxtaposition of motifs imaginable, the most irreconcilable proportions and the most incoherent figuration of space. It seems that no element of the picture agrees with another, not a figure behaves according to natural laws, not an object fulfills the function that would normally be assigned to it.”

Parmigianino, Study for the

Parmigianino, Study for the Parmigianino, Study for the Madonna with the

Parmigianino, Study for the Madonna with theFor these reasons, too, the Madonna with the Long Neck is an extraordinarily modern and innovative painting. And it is also rich in symbolic references: it would be interesting, Ekserdjian notes, to know whether Elena Baiardo Tagliaferri, or Parmigianino himself, enlisted the help of Fra’ Stefano, prior of the servites of the Parma church at the time, who may have been consulted, not least by virtue of the fact of the fact that, although the form and iconography of the work underwent some changes in conception, there are some constants, to detect which Giorgio Vasari ’s description of the work in his Lives comes to the rescue: “At the church of Santa Maria de’ Servi he made in a panel Our Lady with the Son in her arms sleeping, and on one side certain Angels, one of whom has in his arms a’crystal urn, within which shines a cross contemplated by Our Lady; which work, because he was not very content with it, remained imperfect, but nevertheless is a thing much praised in that manner of his full of grace and beauty.” One point on which Vasari insists is precisely the vase with the cross supported by one of the angels on the left (although in reality the Virgin is not contemplating it, because she is turning her gaze toward the Child, and although we do not know whether it is made of crystal and is really reflecting a cross, or whether it is made of some other material, and the cross is painted on the container). It is this vase that is one of the constants, since the cross, even before Parmigianino introduced the detail of the vessel, was present in the composition (indeed, there were two: one held by St. Francis and another resting on the throne). In Ekserdjian’s opinion, the vase, rather than of crystal, is of silver (a similar one is found on the frescoes of the Steccata), and the cross, ofgold, following the curvature of the surface of the container, leaves no doubt that it is part of the vase, and not reflected: the cross, in addition to recalling Jesus’ fate, is also a tribute to the patron, since her eponymous saint is revered as the discoverer of the True Cross of Christ, as we see her depicted, for example, in Piero della Francesca’s frescoes in Arezzo. According to scholar Elizabeth Cropper, the vase may be representing a topical theme, since during the Renaissance a number of treatises were published that compared female beauty, precisely, to vases. The painting itself would be a reflection of the Petrarchan tradition that was still alive in the middle decades of the sixteenth century, and Parmigianino may have been a connoisseur of this tradition, since moreover the patron’s father, Andrea Baiardo, had written Petrarchan poems, some of them with a Marian theme. A tradition that would find its biblical precedent in the Song of Songs.

Indeed, the Virgin’s neck has been seen by many as a reference to a 12th-century Marian hymn, Clara chorus dulce pangat voce nunc alleluia, where there is a verse comparing Mary’s neck to a column (“Collum tuum ut columna turris et eburnea”), and which is obviously derived from the Song of Songs (“Your neck is like a tower of ivory”), in which the figure of the bride is read as an allegory of the Virgin. We do not know whether the artist really intended to allude to the Song of Songs (probably not from the beginning): more likely, again according to Ekserdjian, is the allusion to the iconographic theme of Our Lady of Milk suggested by the nipple that can be seen in transparency under Mary’s white robe. The intermingling of Christian and pagan elements is most evident in the right side of the painting: here, too, the tall column is not to be read as an isolated element, perhaps with the emphasis that many critics have devoted to this singular presence (for example, Sylvie Béguin read in it a reference to Pseudo-Bonaventure’s Meditations on the Life of Christ , where Mary is said to have given birth to Jesus leaning on a column, not to mention the many who have interpreted it as an allusion to the turris eburnea of the Song of Songs). Parmigianino, moreover, paints a row of columns, and not a column alone. So this element is, if anything, to be interpreted for what it is, namely as the only finished part of a temple that remained unfinished, of which we see only the barely sketched outline, which appears in the drawings and can be read as a reference to the “contribution of the ancient world to the construction of Christian civilization” (so Vittorio Sgarbi). Even the colors transport us inside the symbolic universe of time: the cushions on which the Virgin rests her feet, one green and one red, should be read together with the white of her robe, forming the colors of the three theological virtues (white for faith, red for charity, and green for hope).

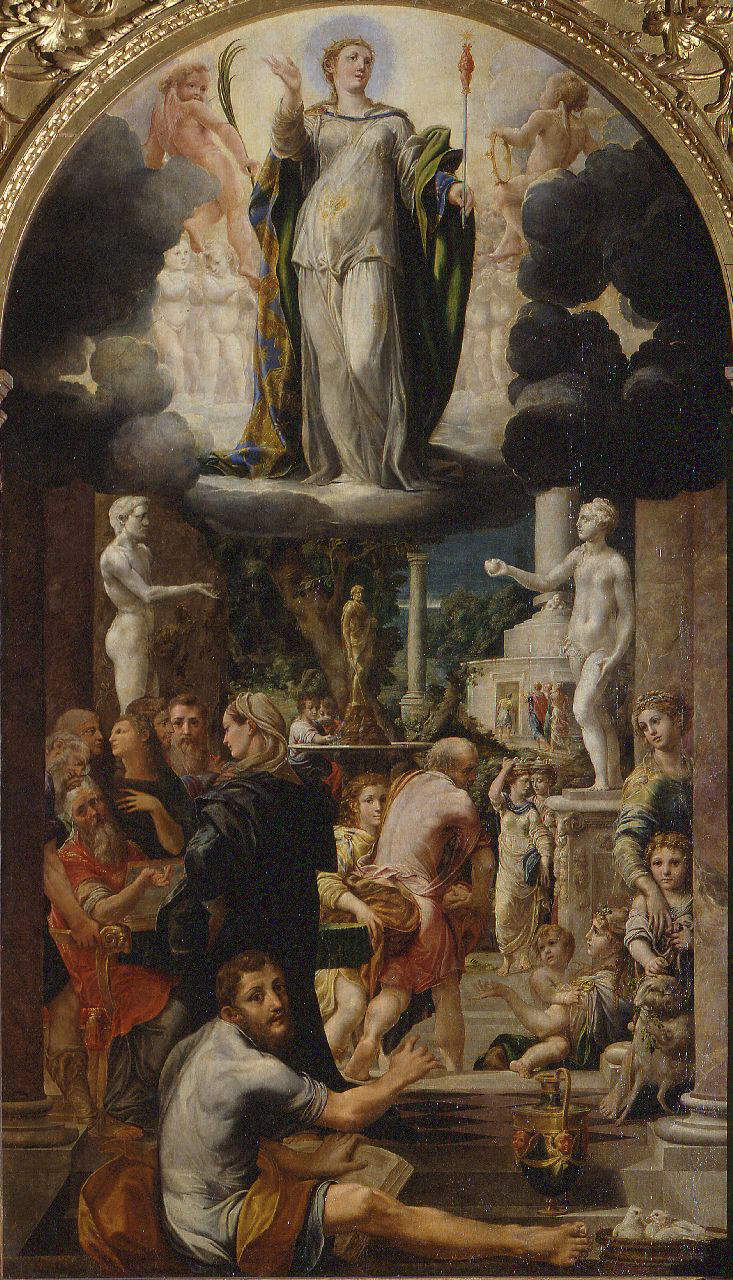

Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, in his book Il Parmigianino. An Essay on Hermeticism in the Sixteenth Century, called into question the Pala della Concezione painted by Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli, an acquired relative of Parmigianino, to give an account of how at the time the theme of the Immaculate Conception was somewhat debated and Bedoli gave a disjointed representation of it (“like a didactic poster”) that may have provided cues for Parmigianino to address, in the Madonna with the Long Neck, the same subject, with recourse to some elements also present in the altarpiece now in the National Gallery in Parma: the temple with the flight of columns, the “disputing character” (i.e., Saint Jerome, read by Fagiolo dell’Arco as a prophet), the “Madonna as crystalline idol.” Parmigianino, according to the scholar, would have linked the moment of the immaculate conception to Mary’s virginity, even alluding with the vase held up by the angel to the " in vitro conception of the alchemist": the vase would thus be the vas hermeticum of the alchemists. The “alchemical” reading of the Long-necked Madonna has, however, seen its quotations fall over the years, as critics have also downplayed the role that interest in alchemy would have played in the last phase of the painter’s life. Even before Fagiolo dell’Arco, Ute Davitt Asmus, in 1968, had read the vase as a symbol of the conception of Christ, while later Elizabeth Cropper interpreted the formal relationships between the body of the Virgin, the vase and the column according to references to Vitruvius’ De Architectura . Many, in essence, are the readings that have been given for this fascinating painting, which has never ceased to cause debate among critics.

As anticipated, Parmigianino failed to complete the work: it was left unfinished in 1539, the year of his escape to Casalmaggiore (the artist was imprisoned in Parma for his failures to comply with the Confraternity of the Steccata, and as soon as he was released he left his hometown to take shelter in the town now in the province of Cremona, and at the time part of the Duchy of Mantua, thus outside the borders of Parma). The artist died the following year in Casalmaggiore itself, without ever having put his hand to the work again. It is enough to take even a cursory glance at the painting to realize its unfinished state: the angel peeking out from under the Virgin’s right elbow is barely sketched, the temple itself, mentioned above, appears hinted at in its outline, of St. Francis we see only a foot, the Child’s head appears poorly finished, and so does the wing of the angel handing the vase to the Virgin. Nonetheless, Elena Baiardo Tagliaferri nevertheless decided to install the altarpiece in her husband’s funeral chapel: we know this from a plaque, now lost, which was placed there presumably on that occasion, and which was handed down by Ireneo Affò in 1784 in his Vita del Parmigianino, in which it is said that the “beautiful painting, commonly called the Madonna of the Long Neck,” was placed in the chapel, with this marble inscription inscribed: “Tabulam praestansissimae artis / sacellumque a fundamentis erectum / Helena Baiardi / uxor equitis Francisci Taliaferri / honori beatissimae Virgini / pro suo cultu in Eam p. / anno MDXLII,” meaning “Helena Baiardo, wife of knight Francesco Tagliaferri, in the year 1542 dedicated this panel of extraordinary art, and the chapel erected from the foundations, in honor of the Blessed Virgin, for her worship.”

The painting’s history is intertwined with that of Florence starting in the 17th century. In fact, in 1674, Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici, a voracious art collector, entered into negotiations with the servants of Parma, through Count Annibale Ranuzzi of Bologna who acted as mediator, to secure Parmigianino’s masterpiece. The deal fell through, however, because the new holders of the jus patronage of the chapel, the Counts Cerati, sued the servites for offering the work to the cardinal. In the end the matter was resolved only in 1698, with the intervention of the duke of Parma, Francesco Farnese, who, in order not to displease Prince Ferdinando de’ Medici, son of Grand Duke Cosimo III, had to put some pressure on the tribunal: the work was therefore taken to Tuscany. The Cerati family, by way of compensation, received a sum to restore the chapel, where a copy of the painting was placed (Prince Ferdinando, by the way, was enthusiastic about the painting: in a letter he called it “finished with the soul”). The Madonna with the Long Neck was also in France for some time: in fact, in 1799, at the time of the Napoleonic spoliations, it was among the works that took the route to France. It remained in Paris until 1815, after which it returned thanks to the work of the Florentine senator Giovanni Degli Alessandri, who was sent to the French capital along with the painter Pietro Benvenuti to claim the return of the Tuscan works stolen during the occupation. Since then, the Madonna with the Long Neck has never left Florence. And even today those who see it in the Uffizi contemplate it as Parmigianino’s most famous and celebrated masterpiece, but also as a particularly unfortunate work, as attested by the inscription on the base of the column, added perhaps when the chapel was consecrated, to warn all concerning what the painting and its painter had to suffer: “Fato praeventus F. Mattoli Parmensis absolvere nequivit.” Francesco Mazzola, from Parma, was unable to finish the work because of adverse fate.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.