The modern history of the stele statues of Lunigiana, the peculiar prehistoric monuments typical of the lands that straddle Liguria and Tuscany, begins on a precise date, December 29, 1827, and in a precise place, the locality Novà di Zignago, a hill in the upper Val di Vara: the first known stele statue was found here, later passed into history as the “Zignago stele,” now preserved at the Museum of Ligurian Archaeology in Genoa. To date, there are 85 stele statues, most of them preserved at the Pontremoli Museum of Stele Statues at the Piagnaro Castle: the most recent find is the head of Mount Galletto, found in March 2021 by a person who was walking in the countryside around Pontremoli. Finding a stele statue, or even simply a fragment of one, is a rare event: to give an idea, suffice it to say that in the last ten years there have been only four finds. And always by chance: usually by hikers walking in the woods or, as in the case of the eighty-second, found near Licciana Nardi, by a farmer who was weeding a vineyard.

The discovery of the Zignago stele caused quite a stir, because no one had ever seen such an object. And the fact that, later, an inscription in Etruscan characters (“MEZUNEMUNIUS,” a word whose meaning is still unknown today) had been added to the sculpture, had led scholars of the time to believe it was an Etruscan artifact. We know, in fact, that the stele statues are much older. We have no written documents that can help us in the task of establishing the dating of the found statues, so it is necessary to rely only on the archaeological contexts and stratigraphies, or on the objects that are sometimes depicted in the stelae statues.Thus, it is possible to establish that the stelae statues were produced along a time span from the beginning of theEneolithic, that is, the end of the fourth millennium B.C., to the seventh-sixth century B.C., with most of the statues being in the middle of theCopper Age (between 2800 and 2300 B.C.C.).

The finds have occurred in a restricted area: almost all in the Magra River basin in historic Lunigiana, in mostly hilly areas, although stele statues have also been found in the mountains. The few stele statues outside the Val di Magra include those found in Lerici and La Spezia, the Zignago stele itself (the only one found in the Val di Vara), and a small group of statues found in Minucciano, the last village in Lunigiana before Garfagnana. The stele statues were found mostly distributed in a few places: in the Selva di Filetto, a wonderful chestnut forest that in ancient times was a sacred place of the Apuan Ligurians, the people who inhabited these places (and who probably used the Selva for religious rites and ceremonies), as many as eleven stele statues were found. Nine statues come instead from Pontevecchio, while six statues were found in Malgrate. The Pontevecchio statues, moreover, represent a special case, because they were all found together, and in the place where they were originally erected (in order of progressive height). And since, if rare are the findings of statues tout court, very rare and exceptional are those of statues in situ (the ones we know of were in fact almost all found out of their context), interesting answers about their function might come from the latter. While it is indeed true that the modern history of stele statues begins in 1827, it can hardly be said that no one had seen the ancient statues of Lunigiana before this date.

To understand why most of the stele statues were found out of their original context, it is necessary to start from another date: 658, the year in which the Council of Nantes was held, during which a direct order was issued against the “lapides” worshipped in the woods. That is, it is decreed that all menhirs and in general ancient devotional stone statues be buried, and that Christian temples be erected over these pits. “It cannot be a coincidence,” wrote archaeologist Roberta Iardella, “that many Christian places of worship (churches, shrines or cemeteries) have arisen on or near sites where stele statues have been found, or that these have been reused for the construction of the buildings themselves, even with different intentions.” The cult of stelae statues endured, in fact, even after the fall of the Roman Empire: this is well attested by an epitaph from the year 752 found in the church of San Giorgio in Filattiera, in which the praises of a certain Leodgard (perhaps a bishop of Luni named Leodegario) are woven, who “gentilium varia hic idola fregit” and “delinquentium convertit carmina fide,” or “destroyed the idols of the pagans and converted sinners.” This plaque has been read as a praise of a physical action on Leodegarius’ part: having materially destroyed the idols of the pagans of Lunigiana, thus the stele statues, and having converted their worshippers to the Christian faith. “It follows that stele statues,” Stefano Di Meo has written, “still in the 8th century CE were seen by the official Christian world as potentially dangerous and therefore capable of hindering the process of Christianization.”

In fact, many stele statues have been found near Christian shrines (such as the three statues in Minucciano), and others have been reused instead: this is the case of the Talavorno stele statue, one of the most recent finds (dating back to 2007), which was reused as a step in the altar of the monastery of St. Benedict, a building already ruined in the 16th century, located in Talavorno, on the banks of the Magra River. Or, of the Sorano VII statue (the stele statues are identified with the name of the place of discovery, and a progressive number), found in 2003 in the locality of Quartareccia, and used as a slab in a Ligurian-Roman box tomb of the 2nd-1st century BC. Again, the Lerici stele was used as a parapet for a well. Another, the Gigliana stele, was even used as a memorial plaque in the village church to commemorate some work that followed in 1779 (it had been bricked into the bell tower). And then, there are the stele statues used simply as building material, and in this sense the cases are many: one can mention for example the one in Codiponte, reused in a wall face.

Scholars have been debating for decades what the function of stele statues was. There are many problems: as mentioned, most of these sculptures have been found out of their context. There is no extensive archaeological record of the necropolises at the site, although useful information could be gleaned from the few known burials. We know virtually nothing about the settlements in the area. And about the ancient inhabitants of these lands, who subsisted mainly on farming, metalworking and little trade with neighboring peoples, we know very little. The first scholar to deal in depth with the stele statues was the La Spezia historian and journalist Ubaldo Mazzini (La Spezia, 1868 - Pontremoli, 1923), the first director of the Biblioteca Civica della Spezia (which is now named after him): in 1908, studying the ancient sculptures of Lunigiana and believing them to be the product of the people of Celtic origin who inhabited these lands, he came to the conclusion that they must have been funerary monuments. With subsequent studies, however, this assumption has been better contextualized, and it is believed to be valid especially for the more recent statues, those of group C (as will be seen below, there are three groups into which the stele statues are classified: A, B and C), sculptures that are much more realistic than the older stelae, and probably animated by the desire to make a portrait of the deceased. Three of these statues, moreover, are accompanied by inscriptions, again in Etruscan characters (one is the aforementioned stele of Zignago, the others are the stele of Bigliolo, one of the most famous because it is among the most conspicuous, and because it has been preserved intact, and the stele of Filetto II): it is not clear what the inscriptions referred to, but it is likely that they were names of persons.

As for the older statues, we need to consider the historical context in which they were made: this is the era during which copper processing began to take hold, an activity that made it necessary to search for deposits and market the products. Thus a decidedly different model of life was established than the previous one, and Lunigiana society, from agricultural, sedentary and matriarchal, experienced an impulse toward a lifestyle based on farming, nomadic and patriarchal. This nomadism, moreover, would transform the Apuan Ligurians into decidedly warlike populations. And it is precisely this lifestyle that is probably at the origin of the use of stelae statues as a method of marking routes, since all finds, even those outside the original contexts, are in any case concentrated in areas that have specific environmental characteristics: usually, along important connecting areas and communication routes. Thus, the hypothesis that the stele statues served as landmarks to be placed near travel routes, population centers or areas that had considerable commercial importance, depicting deities or great ancestors who were placed in these places for their protection, cannot be ruled out.

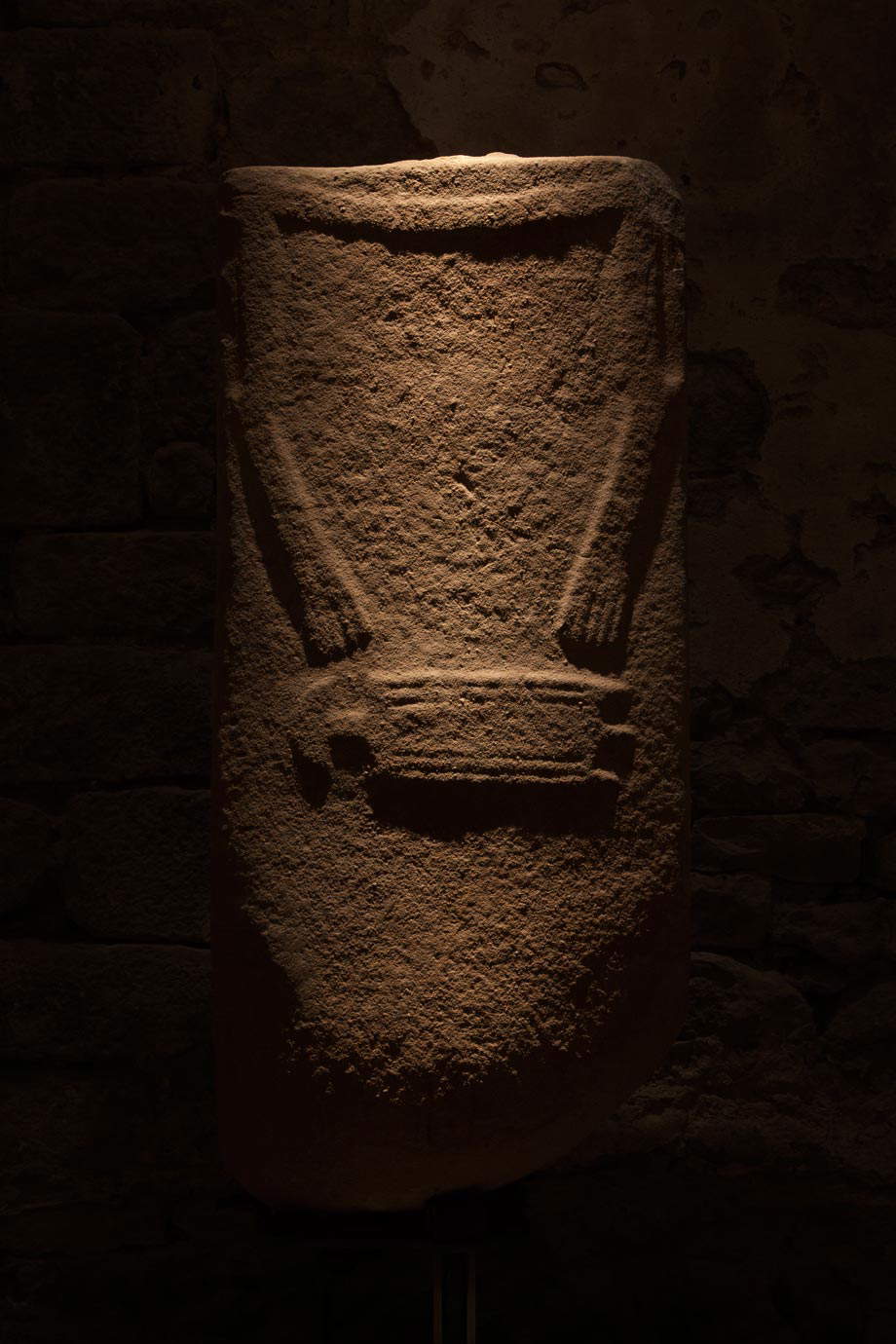

All the stele statues found are made of sandstone, a stone found in abundance in the Magra valley, in the form of blocks: portions were detached, rough-hewn to make the block part reach the desired shape, and then worked in bas-relief to execute body parts, objects and details. The most minute parts (such as eyes, for example) were made with rudimentary drills, which were rotated on themselves while holding them in the hands. At the end of the operation, the sculptors smoothed the whole thing with sand. These are always anthropomorphic statues, which therefore have human likenesses, and in this they differ from other productions of prehistoric sculpture such as menhirs, which, on the other hand, were not intended to resemble the figure of a human being.

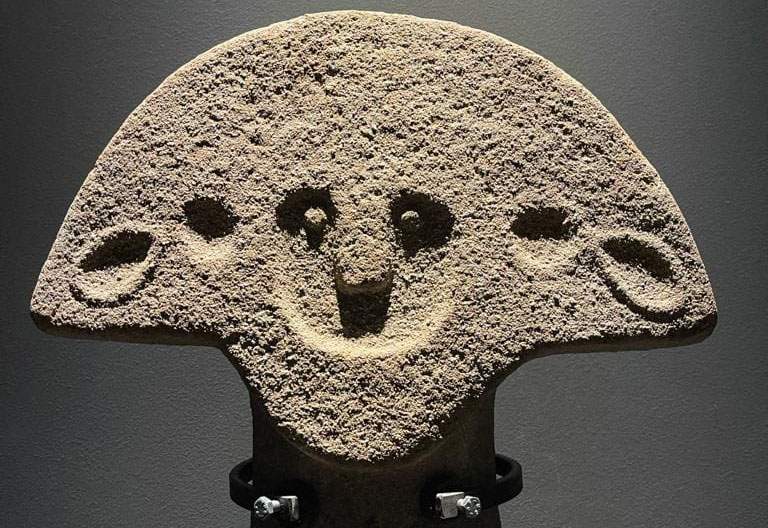

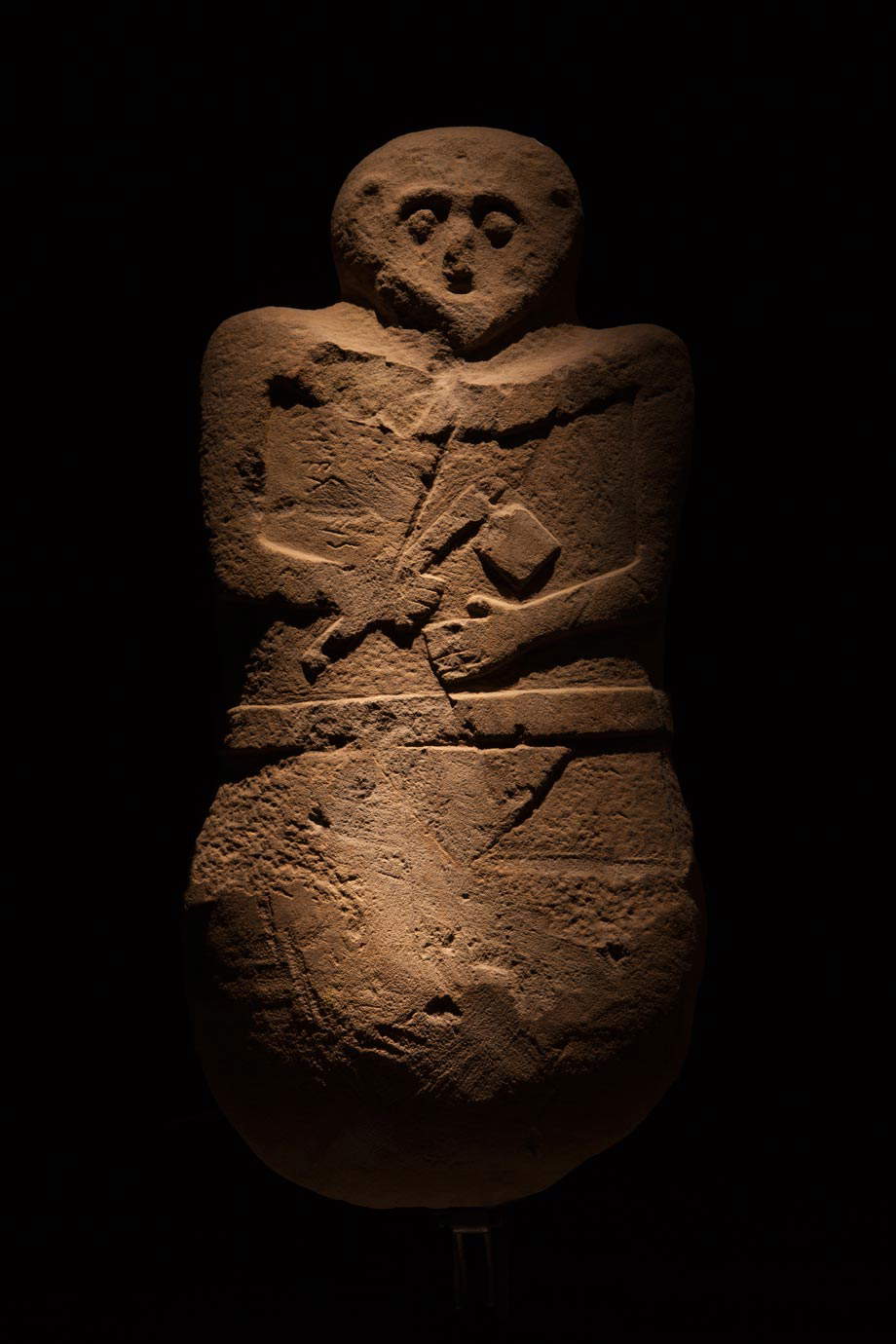

On the basis of their form, the statues are classified, as mentioned above, into three groups: Group A, the one that includes the oldest statues; Group B, which at the present state of knowledge is the thickest; and Group C, that of the most recent and realistic statues. There is also a group of statues that have survived in too fragmentary a manner to fit into one of the three subgroups. The statues of Group A are distinguished by the semicircle-shaped head attached to the body, in relation to which it knows no solution of continuity (only a line at shoulder height is meant to represent separation in a stylized way). In these statues, the arms and hands are represented in a very basic form on the central block that forms the body, while the face is carved in a U shape, leaving the eyes in relief. Interestingly, even in the earliest statues it is possible to recognize male and female statues: the latter, like the Moncigoli I stele, found in 1910 and one of the best-preserved, presents the unmistakable breast suggested with two sphere-shaped reliefs on the chest. The male statues obviously do not present themselves with this element but are sometimes accompanied by objects, such as the Sorano VII stele or like the Casola stele, which present a dagger. The female stele statues have been interpreted by Pia Laviosa Zambiotti as sculptures dedicated to the cult of fertility, where the breasts can be identified as an attribute of motherhood (none of the statues, neither the female statues, which account for roughly a quarter of the total number of stelae found, nor the male statues, however, are presented with the depiction of sexual organs).

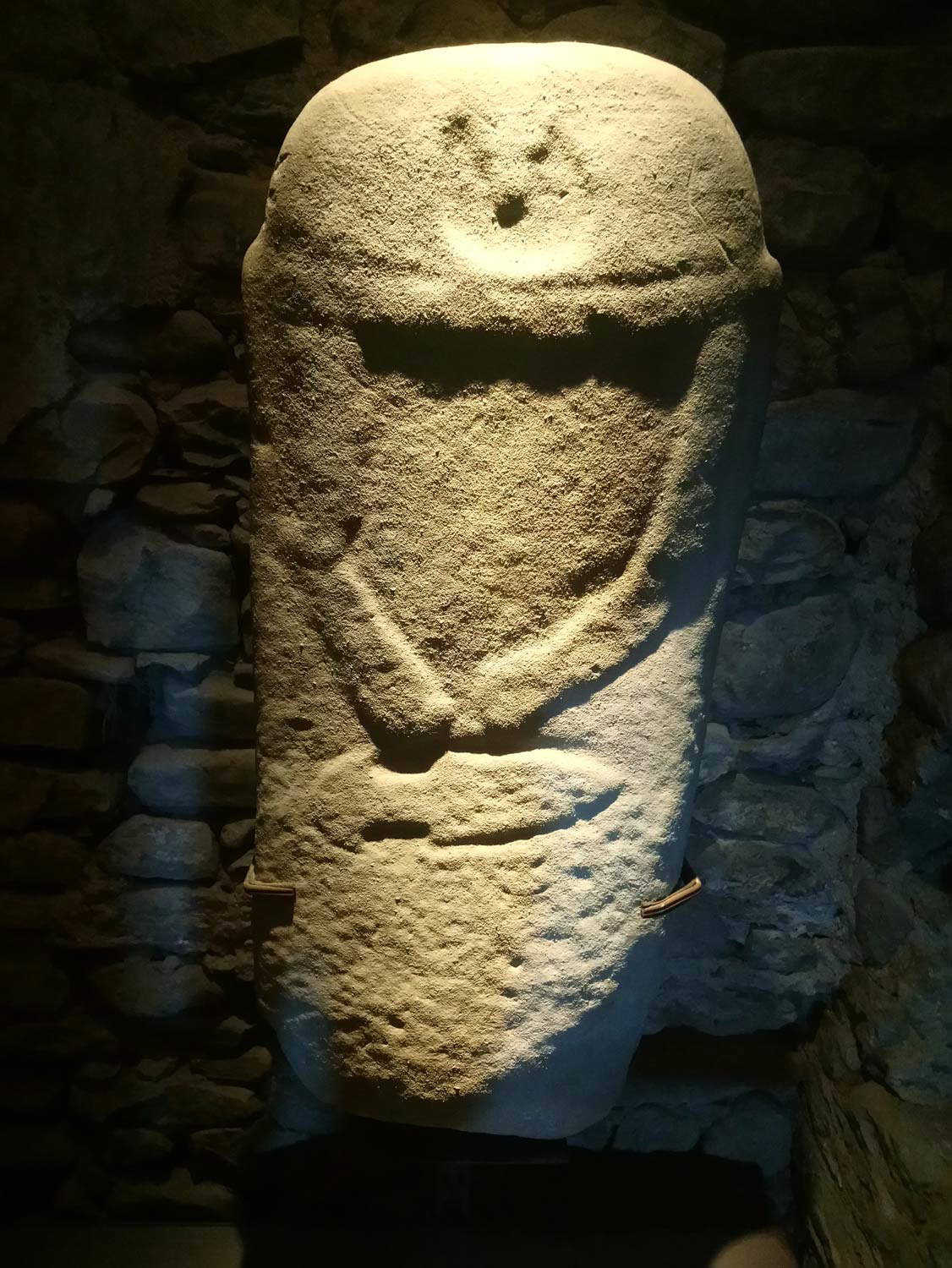

The second group is probably the best known, that of the stele statues most commonly associated with the collective imagination: these are the statues with half-moon-shaped heads, divided from the rest of the body by an often stout neck (see, for example, the Minucciano III stele, one of the best preserved of the group, or the one from Taponecco). The anatomical details, in these statues, are more defined, and so are the objects (in the Canossa I stele, for example, we note a dagger with the pommel also shaped like a half-moon and the blade inserted in a ribbed scabbard). In the stelae of Group B, breasts also appear in female statues (in those of Falcinello and Treschietto we can also see nipples). Moreover, female statues often appear with jewelry, as in the case of the Betolletto stele, which lacks a head but in which we can still make out a ringed goliath. In some statues (such as Philetus VIII or the one discovered in 2021 at Monte Galletto) holes can be seen on either side of the eyes: it is still unclear whether these are ears or earrings.

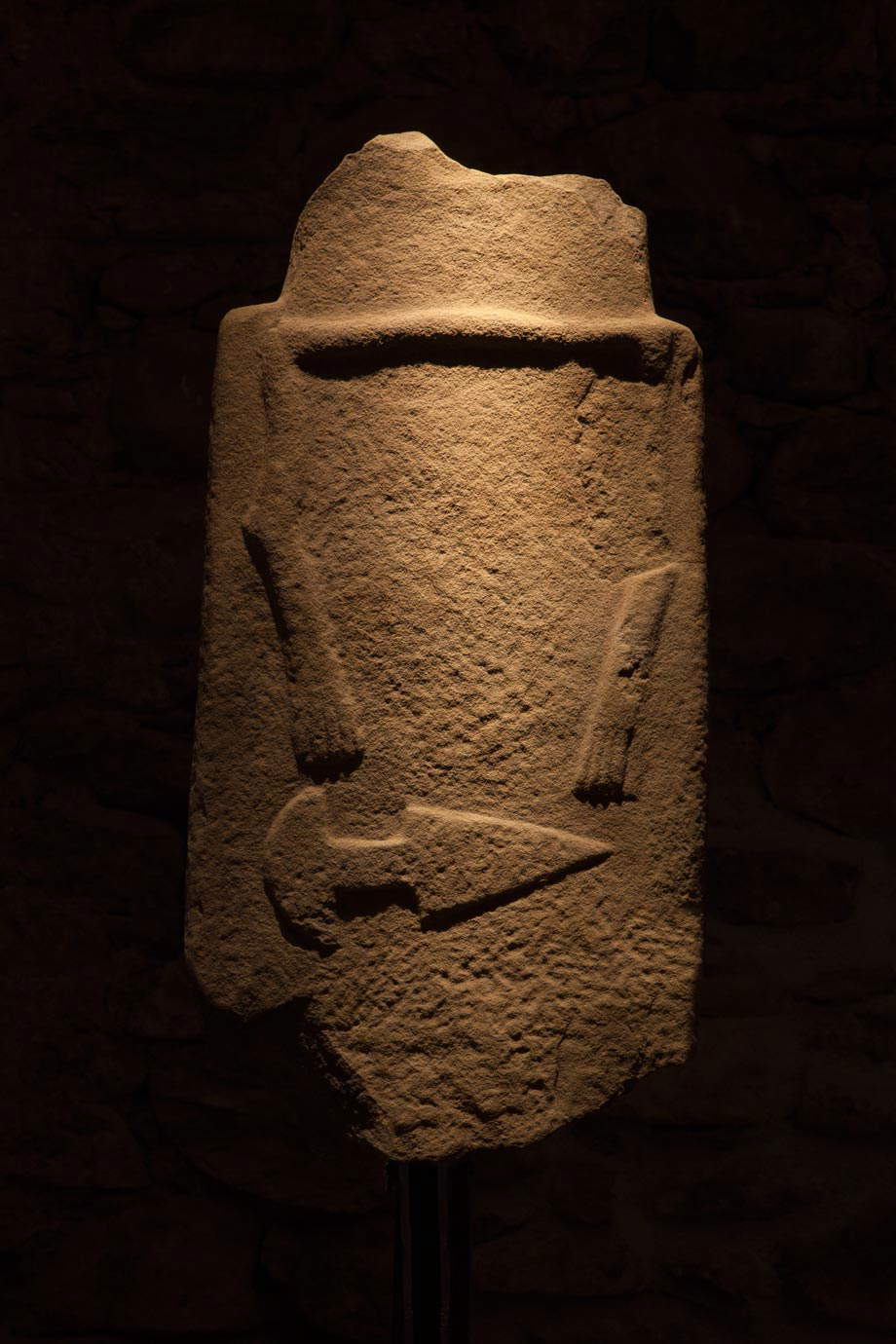

Finally, the Group C statues are, as mentioned, the more recent ones, where the human figure is made with more realistic features. They are also characterized by workmanship that for some details (such as the head, precisely) occurs almost in the round, as in the case of the Filetto II stele. Again, arms and legs are carved in relief and assume less stereotypical poses, and the same is true for facial details. The head is round in shape and is often well defined, as in the case of the Bigliolo stele, which is the best known of the statues in this group. This sculpture also has ears worked in relief, the clavicles arranged obliquely, more realistically than the clavicular line of the group A and B statues, and the arms bent toward the center, holding an axe. The Bigliolo stele moreover also features a belt, immediately below the arms, and a triangular loincloth. In rare cases, some ancient statues were later reworked in later periods: this is the case with the Lerici stele, where a depiction of a warrior in profile, carved in the late Iron Age (6th century B.C.) on an ancient stele from Group A, is observed.

As anticipated in the opening, today most of these ancient prehistoric sculptures are preserved at the Museum of Stele Statues at the Piagnaro Castle in Pontremoli, the institute to visit if you want to have a good knowledge of stele statues, since the sampler kept here offers a complete representation of everything we know about these works, and in addition it allows you to see them displayed side by side with various objects found in the contexts of their discovery, or in any case traceable to the uses of the Apuan Ligurians. It is due to Augusto Cesare Ambrosi (Casola in Lunigiana, 1919 - Florence, 2003), one of the foremost experts on stele statues and author of numerous publications on the subject, the creation of the museum, which has been housed in the castle since 1975 and is the heir to the first collection put together by Ambrosi between the 1950s and 1960s in the town hall of Casola in Lunigiana. The museum in Pontremoli was renovated with a new layout in 2015, which provided the itinerary with new panels and new, evocative lighting to better enhance these ancient sculptures, plus the museum was also equipped with elevators that connect the castle to Pontremoli’s historic center.

Other statues are preserved in various museums: this is the case with some stelae such as the Zignago stele (which, as mentioned, was the first to be found and is at the Museum of Ligurian Archaeology in Genoa), the Moncigoli I (kept at the National Archaeological Museum in Florence), the Fosdinovo stele (at the Castle of Castiglione del Terziere near Bagnone), several statues found in the Selva di Filetto (which are at the Museo Civico della Spezia), the Reusa stele, one of the most important of group C (kept at the Museo del Territorio dell’Alta Valle dell’Aulella in Casola in Lunigiana). One statue, the Filetto II, found around 1870, is instead walled in the courtyard of Palazzo Bocconi in Pontremoli. A special case is that of the Canossa II stele, found in 1976 in the woods between Lusuolo and Canossa, and left in situ.

It is therefore necessary to travel to Lunigiana to discover the fascination of these extraordinary sculptures: as Augusto Cesare Ambrosi wrote, “they are the surviving traces of a great religion that, as the Stone Age passed and the great invention that was metals spread, transformed stone into an object of worship, into a sign of perennial memory capable of overcoming and conquering time.” As for the identification, it matters little according to Ambrosi: more important is their function: “Whether they are real deities or just emerging figures, warriors and great mothers, who were wanted to be remembered and commemorated, does not matter much. This mysterious and evocative crowd, these stones, were certainly monuments in which a charge of affection and love was transfused, which, in all cases, must have flowed into that heated sentiment we now call idolatry.” Witnesses of a very distant past, stele statues today preserve the memory of the ancient peoples who inhabited the Lunigiana and who, with these simple, almost primordial means, expressed their way of seeing life.

Essential bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.