Love according to Francesco Hayez. From the romantic to the secret, five works by the great painter

Perhaps the artist the collective imagination associates with love more than anyone else is Francesco Hayez (Venice, 1791 - 1882), the most famous of the Italian romantics. His paintings celebrated love in different forms and telling the most diverse stories. In this gallery we have chosen five of his works by associating them with as many types of love, and we have accompanied them with five comments taken from the bibliography on the artist. Happy reading!

Romantic Love: The Kiss (1859; oil on canvas, 112 x 88 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera)

"Where the romantic impetus prevails over the theme [...] we have paintings like The Kiss, perhaps the most Hayezian of all. Around this subject, of irritating perfection, a whole series of negative conjectures can be exercised. But it is no coincidence that its conception coincides, dates in hand, with the second campaign of independence. That feathered-hatted lover (D’Annunzianism will rename this painting Paolo and Francesca) is thus, to the alert observer, the volunteer about to take up arms against the hated tyrant. That same tyrant who had appointed (by the mouth of Radetzky) Signor Francesco Hayez to the directorship of the Brera Academy, and then ordered him to paint a portrait of the emperor. And if it is true that in the Kiss echoes the roll of the drum that calls with Garibaldi (or rather with the Piedmontese, if we are going by the conservative inclinations of the master), it is a civil sentiment that Hayez represents behind the screen of an amorous episode. An episode that nevertheless had to upset the well-wishers because of the unusual realism of the scene: the way the young man holds his beloved’s face in his hands; the nonchalant attitude, almost like a stolen snapshot, caught on the spot; finally, the duration of a kiss in public that in 1859 must have appeared scandaolous, taale to invoke, had it existed, the immediate intervention of that Hays Code that in Hollywood established in minutes seconds the duration of embraces" (Carlo Castellaneta, Un fotografo di corte e un regista di melodrammi in Sergio Coradeschi, L’opera completa di Hayez, Rizzoli, 1971)

|

| Francesco Hayez, The Kiss (1859; oil on canvas, 112 x 88 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

Dramatic Love: The Last Kiss Given by Juliet to Romeo (1823; oil on canvas, 291 x 201.8 cm; Tremezzina, Villa Carlotta, Botanical Museum and Garden)

"The painting, inspired by the popular Shakespearean tragedy and commissioned by one of the most famous collectors of the time, Giovanni Battista Sommariva, was exhibited at Brera in 1823 along with the painting, also of large format, purchased by the German Count Schönborn-Wiesentheid, taken instead from an older source, the novella by Da Porto, and representing The Marriage of Juliet and Romeo (Pommersfelden, Graf von Schönborn Kunstsammlungen). The story of the two lovers, one of the flags of Romanticism even in melodrama, owes its fortunate popularization to Hayez, having been reprised, later in three other paintings, in 1825 and twice in 1830, until the transposition, starting in 1859, of this motif in the popular Kiss series. Thanks to many reproductions and reductions in various media, but also to an extraordinary critical fortune, the painting became a cult work of the Romantic nineteenth century. Everyone has admired different elements in it, such as the evocative and faithful reconstruction of the setting, a sensuality reminiscent of Titian, or the sumptuous rendering of the costumes, such as the ’maiden’s dress, whose luster imitates the finest velvet in France.’ It was the leader of Romantic criticism Defendente Sacchi who saw in it a kind of manifesto, since ’his Juliet is certainly not Venus and is not the ancient woman [...] she is beautiful, but beautiful of her love,’ while ’Romeo is not the Antinous, nor the Apollo, yet he is with desire regarded by feminine curiosity and announces to you the flower of the brave and lovers.’ But it was the German correspondent of the ’Kunst-Blatt’ in Milan, the influential Ludwig Schorn, who had opened, being impressed by the work at the exhibition, the debate, denouncing the excessive truth of that ’kiss’ that ’is not the tender love of a pure enchanted soul,’ but ’is voluptuous’" (Fernando Mazzocca in Romanticism, edited by Fernando Mazzocca, exhibition catalog, Milan, Gallerie d’Italia, from October 26, 2018 to March 17, 2019, Silvana Editoriale, 2018)

|

| Francesco Hayez, The Last Kiss Given by Juliet to Romeo (1823; oil on canvas, 291 x 201.8 cm; Tremezzina, Villa Carlotta, Museum and Botanical Garden) |

Literary Love: Rinaldo and Armida (1812-1813; oil on canvas, 198 x 295 cm; Venice, Galleria dell’Accademia)

"Still extraordinary appear the maturity and originality of this work executed by Hayez in his twenties for the renewal of his fourth year of retirement in Rome, where it was exhibited early in 1813 at the Accademia Nazionale in Palazzo Venezia and then presented again in the summer of the same year at the Venetian Academy of Fine Arts. The importance of the painting, if not the most beautiful, the most innovative of Hayez’s neoclassical training, explains the prominence with which the events of its execution, linked to the confident expectations of its supporter Canova and to a special relationship with the two models, especially the beautiful young woman of nineteen used for the sensual figure of Armida, will be recalled in the Memoirs of its author. Moreover, his choice of theme, inspired by Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata, brought him closer to the sensibility of the German Nazarenes, who were then beginning to make their mark in Rome, and anticipated the future Romantic climate. In this sense, the comparison with the Venetian painting tradition in the direction of the warmer Titian naturalism is significant. In addition to the pastiness of the two nude bodies, the beautiful detail of the weapons, particularly the helmet, hanging like a trophy against the magical background of the landscape is an extraordinary revealing spy. The symbolic motif and at the same time the display of virtuosity of the reflected images between the shield and the mirror seems another 16th-century echo, probably from Tintoretto’s Susanna and the Old Men in Vienna. A decisive novelty is represented by the natural setting, resolved by creating a garden that seems to anticipate, probably on the basis of the reading of the treatises of Cesarotti and Pindemonte, who had drawn inspiration from the reinterpretation of this episode of Tasso, the Romantic garden realized by Giuseppe Jappelli;" (Fernando Mazzocca in Romanticism, edited by Fernando Mazzocca, exhibition catalog, Milan, Gallerie d’Italia, from October 26, 2018 to March 17, 2019, Silvana Editoriale, 2018)

|

| Francesco Hayez, Rinaldo and Armida (1812-1813; oil on canvas, 198 x 295 cm; Venice, Galleria dell’Accademia) |

Secret Love: Bianca Capello’s Escape from Venice (1853-1854; oil on canvas, 208 x 159.5 cm; Berlin, Staatliche Museen)

"Francesco Hayez, a leading figure of Romanticism in Milan in the 19th century, became famous with large-scale, emotionally charged, sometimes tumultuous historical scenes and psychologically elaborate portraits. He received major commissions and numerous awards, and was appointed director of the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in 1850. Berlin collector Joachim Heinrich Wilhelm Wagener commissioned him to paint Fuga da Bianca Capello da Venezia during a visit by the artist to Milan in 1853. Hayez collected historical material from the mid-16th century: Bianca Capello, daughter of Venetian nobleman Bartolomeo Cappello and later second wife of Francesco I de’ Medici, had a love affair with Pietro Buonaventuri, a servant who became a member of the Salviati family. One morning, after one of her nocturnal adventures, she found her parents’ house locked. The artist chose the exact moment when Bianca, initially in despair, takes her fate into her own hands and decides to run away with her lover. The gondolier in the background is ready to leave" (Birgit Verwiebe, file for the painting in the catalog of the Alte Nationalgalerie Berlin, 2019)

|

| Francesco Hayez, Escape of Bianca Capello from Venice (1853-1854; oil on canvas, 208 x 159.5 cm; Berlin, Staatliche Museen) |

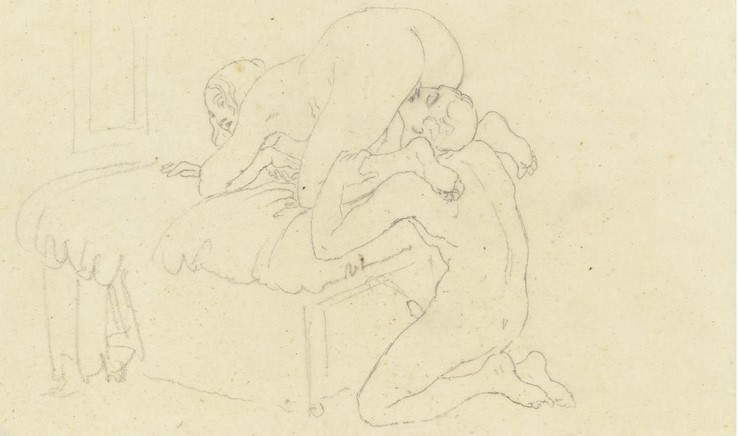

Passionate Love: Sex Scene between Francesco Hayez and Carolina Zucchi (c. 1821-1831; black pencil on tissue paper; Private Collection)

"It is a passage from the artist’s Memoirs that reveals to us that it was actually a young Milanese woman, the 20-year-old Carolina Zucchi, who lent him her likeness [for the private collection’sAnnouncing Angel that reappeared in 1997, ed.], just as she did for so many paintings executed between 1820 and 1830. A woman, this Carolina, emancipated and of decisive sensuality who was portrayed again in a famous painting, known by the misleadingly censorious title of The Sick Woman (she actually lies in bed after an affair with the artist) now at the Civic Gallery of Modern Art in Turin. It had come there, after originally belonging to Hayez himself who disposed of it very reluctantly, from the fine collection of King Carlo Alberto’s Intendant Pietro Baldassarre Ferrero [...]. In addition to the image in which she was caught in intimacy and the idealized one, there is a third beautiful portrait of Carolina, still preserved at the descendants of the effigy, together with an extraordinary Self-portrait by Hayez, represented with a cap lowered on her forehead and a defiant look. The two paintings formed a pendant, almost a pledge from the artist to the beloved model whom contemporaries mischievously called the ’Fornarina dell’Hayez,’ perfectly informed about a relationship that went far beyond that with an inspiring muse. To what boundaries he reached is unequivocally demonstrated by another testimony left by Hayez to Zucchi, and also left to his heirs, the astonishing series of nineteen (but originally there must have been twenty) erotic drawings, executed with a continuous stroke on tissue paper. The two lovers are portrayed, unashamedly revealing the passionate nature of their relationship while exhibiting the whimsical variety of their amatory poses. It is, of course, an exceptional ensemble that can be included, for the boldness and quality of the images, in the best tradition of eroticism in art, from antiquity to Giulio Romano, Füssli, Pinelli and Picasso" (Fernando Mazzocca in Hayez privato: arte e passioni nella Milano romantica, Allemandi, 1997)

|

| Francesco Hayez, Sex Scene between Francesco Hayez and Carolina Zucchi (c. 1821-1831; black pencil on tissue paper; Private collection) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.