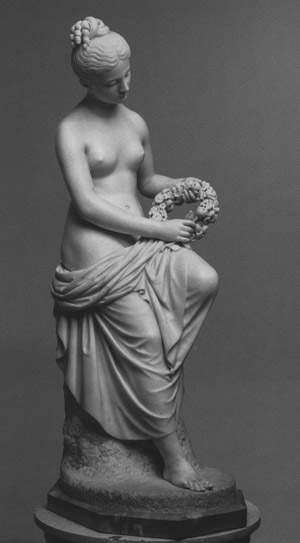

Louis Bienaimé's La Pastorella: a sweet and delicate neoclassical work

|

| Louis Bienaimé, Shepherdess (1837; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

“A gentle Shepherdess vaguely coiffed in symmetrical group her hair, has on her forehead the most graceful thought. She meditating studiously and quietly inclines her head a little to one side to gaze at a vague garland of flowers, which she holds suspended from one hand; and she looks, and squares, and thinks where she has to place in beautiful harmony another new flower, which she holds between her fingers. Her mantle slides to the ground, which she no longer heeds (all intent on the work), and on the beautiful girdle she stops where she over a raised knee holds it. He stands by her side, resting his terga on the ground, and standing upright in the two feet in front the faithful dog, which raising its muzzle, to which the long ears make a noble counterbalance, seems to ask for some caress from the tender mistress.” This is how the poet Angelo Maria Ricci described Luigi Bienaimé’s splendid Shepherdess in 1837 in a booklet devoted to the sculptures of the Carrarese artist, which Ricci had seen in Bienaimé’s Roman atelier.

Two versions of this delicate statue exist. The first dates precisely from 1837: it is signed and dated, and is the one Ricci describes in his work. The commission was prestigious: it was in fact sculpted for Grand Duke Michail Pavlovic Romanov, brother of Tsars Alexander I and Nicholas I of Russia. The ideal “go-between” was probably Nicholas I himself, who from the time of his accession to the Russian throne (in 1825) had shown a great passion for the Italian art of the time, so much so that Russian art critics also decided to deepen their relations with Italy: in the following years, the “Journal of Art”(Chudozestvennaja gazeta) devoted extensive coverage to neoclassical and purist sculptors, and great attention was paid to the young men who had entered in the wake of Antonio Canova and Bertel Thorvaldsen. These included Luigi Bienaimé, born in Carrara in 1795.

|

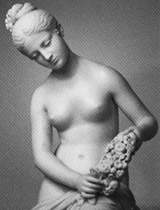

| Luigi Bienaimé, Shepherdess (1854-1855; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

Relations with Russia also intensified as a result of the many visits to Italy by leading members of the Russian aristocracy. In 1845 it was the turn of Tsar Nicholas I himself, who in December of that year landed in Civitavecchia and moved to Rome, where he had the opportunity to visit the ateliers of all the artists working in the city. And the visit almost always resulted in commissions for the artists: Bienaimé was probably the most fortunate, as he obtained four commissions. This is the historical and cultural context in which the creation of the two versions of the Shepherdess is set.

There are no major differences between the two works: the most conspicuous, if we exclude the difference in size (the 1837 version is about half a meter taller), is the dog accompanying the shepherdess, present in the older version, which compared to the newer one also has drapery with slightly thicker folds at thigh level. The pose, however, is identical. The girl is completely nude, except for a veil that encircles her legs, and she is weaving a garland of flowers. She is caught in a careful expression, focused on her work. She is a young girl, we can tell by the features on her face, and her wonderful nude body is imbued with a youthful freshness that strikes the viewer with her slender, elegant forms that are not without a certain sensuality. Bienaimé has lavished a great deal of attention on the rendering of the hands, tapered and with elongated fingers that almost seem to caress the flowers, and of the feet, delicate and feminine, resting naturally one on the ground and the other on the rock on which the girl has leaned. These features make Bienaimé’s Shepherdess one of the most interesting achievements of neoclassicism, of which the artist from Carrara was one of the most staunch supporters, as he was a pupil of the “purest” of neoclassical artists, Bertel Thorvaldsen: we can therefore consider the Shepherdess as a sort of hymn to ideal beauty, to gracefulness, grace and also to the great simplicity that were among the founding values of neoclassicism.

|

| Detail of the face of the 1854-1855 Shepherdess |

In his description, Angelo Maria Ricci also attempts to give the Shepherdess an identification: “In this young shepherdess perhaps the sculptor wished to portray the ancient Glicera, who Pliny placed among the inventors of the Fine Arts for the marvelous artifice, whereby she used to arrange her garlands offered to the temples of the Numi.” According to a story that mixes elements of reality with legendary elements, Glicera (whose name in Greek means “the sweet one”: a name that would be very suitable for our Shepherdess, given her great tenderness) was a girl of noble spirit who was credited with the invention of artificial flowers, and garlands of intertwined flowers. She would have been the beloved of the painter Pausia of Sycion, who lived in the 4th century B.C., and who would leave, among his various works, a portrait of Glicera herself.

|

| Detail of the Shepherdess of 1854-1855 |

We have spoken about the circumstances under which the first version was executed. On the second one we have only recently been able to shed light: the Shepherdess without a Dog was also thought to date back to the late 1830s, or at most to the early 1840s, so that it was a little later than the 1837 execution. Documents were later discovered that the Shepherdess was executed between 1854 and 1855 for the young Prince Nikolai Borisovic Jusupov, who was part of Nicholas I’s entourage and was one of the most important art collectors and patrons of the tsarist court at the time. Jusupov had also visited Louis Bienaimé’s Roman atelier and requested two works from him: in addition to the Shepherdess, also the Dancing Bacchante. Both the latter work and the two shepherdesses are now in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

The Italian public, for a few months, has the opportunity to see live the most recent version of the Shepherdess (in addition to the Dancing Bacchante and other works by Luigi Bienaimé) at the exhibition Canova and the Masters of Marble (in Carrara, Palazzo Cucchiari, until October 4, 2015): a truly interesting opportunity to see these and other works of extraordinary beauty and of the highest historical and artistic interest, as well as to delve into the fruitful cultural relations between Carrara and Russia during the 19th century.

|

| The Shepherdess of 1854-1855 at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.