Lorenzo Lotto's unconventional Adoration: human and divine live in the humility of Christmas

Few artists knew how to give a work such a touch of innovation and expressive freedom as Lorenzo Lotto (Venice, 1480 - Loreto, 1556/1557). This can be clearly seen in theAdoration of the Shepherds preserved at the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo in Brescia, in which what immediately catches the eye of the viewer is that unusual and spontaneous gesture that binds the Child Jesus to the lamb supported by a shepherd. What Lotto depicts on the canvas is not the usual scene in which everyone is in adoration of the Infant Jesus: here, in fact, the painter wanted to put the observer in front of a scene that shows the birth of the Infant Jesus but at the same time anticipates the theme of the Passion, using a series of contrivances and original compositional solutions that sprang from the mind of an artist who was, to say the least, unconventional, but still sometimes underestimated today.

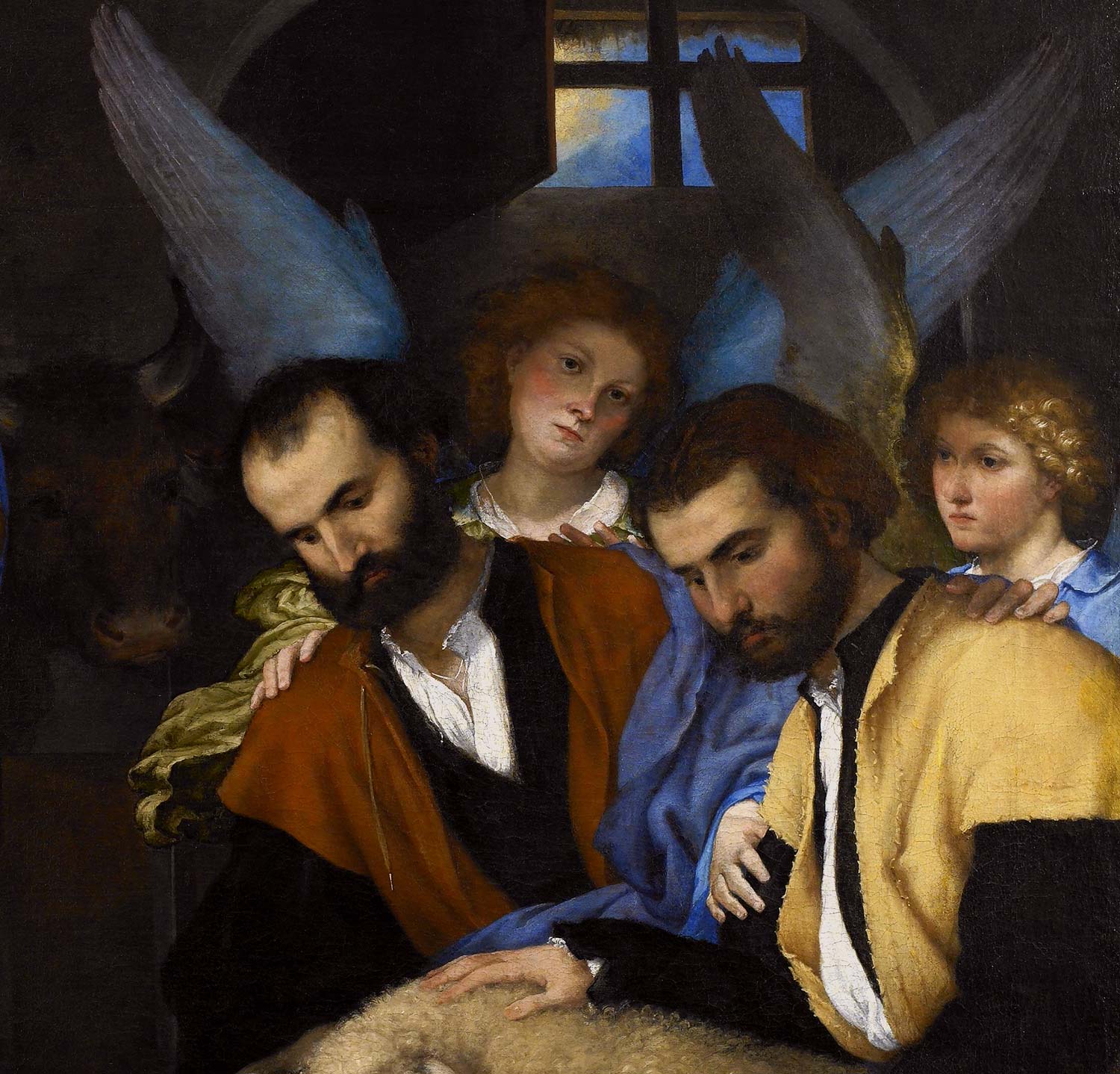

This is 1530, in the mature period of his artistic production and during his second stay in Venice, after his return from the Marche region. ThisAdoration of the Shepherds is set inside a hut. A window with an open sash and glass divided into four parts to evoke the cross can be seen under an arch, while the open aperture on the left makes visible a glimpse of the sky illuminated by golden glimmers and the hut’s outer canopy built of wooden beams. Despite the two openings in the background, the light that illuminates almost the entire composition seems to arrive frontally and centrally the most illuminated figures are in fact those in the very foreground, degrading more and more to the half-light in which the ox and the donkey are enveloped; the former is almost confused with the wall of the hut, of the latter we can see its silhouette, with its long ears, against the light because it is in front of the doorway. The light illuminates the faces and robes of the Madonna and the shepherds, as well as the little body of the Child lying on the white cloth and part of the Virgin’s robe and mantle. More in shadow are the faces and long wings of the angels and the face of St. Joseph. All the characters are absorbed, in contemplation of the little being who reaches back to caress the sweet little face of the lamb, with whom he immediately establishes a relationship of empathy. All except the angel in the center of the arch, who is looking toward the viewer to make him a participant in the scene. It is a silent, muffled scene in which the only momentum is represented by the Baby Jesus’ gesture, as opposed to everything else that is still.

The Child is placed in a large rectangular wicker basket filled with straw, which welcomes the Madonna kneeling before her son. She has her hands joined in prayer, her face bowed toward him, and is wrapped in very large draperies that fall from her head; in particular the blue mantle that first covers her shoulders, then her arms, and finally forms the basis for the white cloth on which Jesus is placed. Behind her Saint Joseph, in profile, watches over the scene. In a symmetrical position to Our Lady are the two shepherds, concentrated in the expressions of their faces, and the one more in the foreground, as already stated, holds the lamb from under its belly and with his other hand caresses its back, offering it as a gift to the Child. Behind the shepherds, stand two angels, with long wings and blue and gold silk robes, who accompany the former by resting their hands on their shoulders, as a sign of protection but also of encouragement. In the words of Roberto Longhi, the composition is reminiscent of his sacred conversations transformed into “a confidential reunion that unites on the same ground and distributes the same disposition to the divine and human characters.”

Contrary to what appears from the dark brown and light brown cloth tunics, the two shepherds belong to an elevated social class: in fact, under the tunics they wear white shirts with ruffled collars and cuffs, black velvet farsetti and “jagged” breeches, and violet stockings stopped at the knee by blue ribbons. The clothing of fashionable 16th-century nobles is here purposely disguised by humble shepherd’s tunics to make the sacred scene more humble. The resemblance in the faces suggests that the two shepherds are consanguineous or even brothers, and on the basis of this, in addition to the physiognomic features as real people, it has been assumed that they have the faces of the painting’s patrons : either the Baglioni brothers of Perugia or the Gussoni brothers of Venice, in any case noblemen. In 1824 the dealer and antiquarian Giovanni Querci wrote to Count Paolo Tosio, with whom he had close relations, to propose the sale of the painting in question “made for the Baglioni counts of Perugia.” this is precisely how it arrived in the collection of Paolo Tosio, to whom we owe the birth of the Tosio Martinengo Pinacoteca, which in fact originated from the collections of paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures and art objects that the count wished to donate to the Municipality of Brescia in 1832, “so that they may be perpetually preserved in Brescia itself for the public convenience,” as we read in his will drafted in that year, but which became enforceable in 1846 after the death of his wife Paolina. If in 1824, however, reference was made to the Baglioni counts, it was not until two years later, in 1826, that reference was made for the first time in Paolo Brognoli’s Nuova Guida to the Gussoni brothers of Venice.

Among the wicker weavings of the basket was discovered, during the restoration of the painting in the 2000s, the autograph signature and date “L.Lotus 1530”: in that year Lorenzo Lotto was staying in Venice and this has directed scholars to a Venetian commission; here the artist was famous as a portrait painter and the Gussoni family (the probable commissioners) owned paintings and properties of considerable importance. Whether it can be traced back to the Gussoni brothers of Venice still remains a hypothesis, as there is still no certainty about it.

The painting’s ancient provenance is also still unknown: from the size and intimacy of the scene it is at any rate believed to be of private, palace chapel destination. We do know, however, that it entered the collection of Count Paolo Tosio thanks to his purchase between August 24, 1824 and January 5, 1825, and that he placed the work on the fireplace of his house in the morning room near two portraits by Giovan Battista Moroni and the Virgin Annunciate by Alessandro Bonvicino, known as Moretto.

The figure of the Madonna deserves some reflections. Kneeling on the ground inside the basket where the Child is also placed, the Virgin reflects the iconography of the Madonna of Humility, which spread from the inisio of the 14th century: she is in fact not represented enthroned, but on the ground as a sign precisely of humility (from the Latin humus, earth). Moreover, in the ring finger of her right hand she wears a ring: this could be a reference to the Holy Ring, that is, the wedding ring that according to tradition St. Joseph gave to Mary for their marriage. The jewel object of devotion (on which a gemmological analysis was carried out in 2004 that recognized it as chalcedony) is kept in a chapel in Perugia Cathedral and is protected by no less than two safes for the opening of which fourteen keys are required.

The particularity of this painting, however, lies in the presence of elements that refer to Christ’s future sacrifice: the serenity of the birth is shadowed, therefore, by his destiny. First, by the little lamb that the shepherd offers him as a gift and which the Baby Jesus caresses on the muzzle: it is a clear allusion to the Passover sacrifice (“Behold the lamb of God, behold him who takes away the sin of the world!” Jn. 1:29), performed by Christ to save mankind. Alluding instead to Jesus crucified and thus to the Passion is the cross created by the division into four parts of the glass of the small window under the arch, while the wicker basket has a rectangular shape reminiscent of a sarcophagus.

This dualism of birth and sacrifice is also present in another work by Lorenzo Lotto, preserved at the National Gallery of Art in Washington: the Nativity signed and dated “L.Lotus 1523.” If in the foreground both the Madonna and St. Joseph are kneeling in adoration of the Child (usually St. Joseph is depicted standing and more aloof than the Madonna who is always close to her son) and three angels in flight are singing the melody of a score that they are all holding up together, in the shadier part hangs a crucifix, revealing to the viewer the destiny of that Child who now lying in a wicker basket is waving his arms and feet in a sign of vitality. And the wood on the ground on which the artist has placed his signature and date is also to be read both as a reference to the wood of the cross and to Saint Joseph’s trade as a carpenter.

In both paintings Lorenzo Lotto is capable of expedients and suggestions that attest to his originality and his constant search for new compositions, which still attract the gaze of those who observe one of his works. In particular, in theAdoration of the Shepherds at the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo he creates an intimate scene dense with symbols, populated with various characters free in their poses. A delicate painting where the human and the divine coexist as a sign of thehumility of Christmas.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.