by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 14/09/2017

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Lorenzo Bartolini's Ammostatore is one of the most important works in the history of Italian art because it effectively ushered in purist art.

It is very curious to think that one of the capital works in the history of Italian art, namely Lorenzo Bartolini ’s (Savignano di Prato, 1777 - Florence, 1850)Ammostatore, had gone essentially unnoticed, as scholar Stefano Grandesso recalled in a paper on the developments of neoclassicism. Or at least, it went unnoticed in its first drafting: the Prato sculptor had in fact begun modeling his Young Grape Presser in 1816 (we still preserve the plaster, at the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence), and would translate it into marble shortly thereafter. The work later ended up in the collection of a French nobleman, Count James-Alexandre de Pourtalès-Gorgier, who bought it directly from the artist in 1818. It was long given up for lost, since in 1865, following the auction of the count’s estate, it took an unknown destination, but many have reasonably wanted to locate, in theAmmostatore that in 1926 entered the collections of theHermitage in St. Petersburg where it still stands today, the original that was thought to be lost: perhaps, it ended up in Russia just after the auction. It is no mystery that the Jusupov family, among the most prominent in Russia at the time, had a great admiration for Bartolini’s art, and it is therefore to be expected that they were the buyers who secured the work at auction: scholar Sergei Androsov writes, in the catalog of the exhibition Dopo Canova. Paths of Sculpture in Florence and Rome (Carrara, Palazzo Cucchiari, from July 8 to October 22, 2017), an exhibition in whichAmmostatore figures among the top protagonists, that Princess Zinaida Jusupova and her son Nikolai Jusupov, between the 1850s and 1860s, took to purchasing various sculptures in Italy and France. These included Trust in God, which Zinaida Jusupova commissioned directly from Bartolini: the artist did not have time to complete it and it was finished in 1858 by Pasquale Romanelli (Florence, 1812 - 1887). It is likely that theAmmostatore was also among these works: in fact, Bartolini’s masterpiece appears to have been kept in the family palace until 1926: then, as anticipated, it ended up in the Hermitage, following the dismantling of the Jusupov Palace.

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, The Ammostatore (c. 1816-1818; marble, 128 x 43 x 41 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, model for L’ Ammostatore (c. 1816; plaster, 128 x 43 x 41 cm; Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia) |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, L ’Ammostatore at the exhibition Dopo Canova (Carrara, Palazzo Cucchiari, 2017) |

Instead, the second drafting of the sculpture, which Lorenzo Bartolini executed between 1842 and 1844 for Count Paolo Tosio Martinengo, caused a stir. However, many things had changed since 1818: meanwhile, the artist had acquired considerable fame, and obviously the public and critics were showing more attention to him. Moreover, in the 1940s we were in the midst of the debate on purism: precisely in 1842, the painter Antonio Bianchini (Rome, 1803 - 1884) had written a pamphlet entitled Del purismo nelle arti, which was signed by Friedrich Overbeck (Lubecca, 1789 Rome, 1869), Pietro Tenerani (Carrara, 1789 - Rome, 1869) and Tommaso Minardi (Faenza, 1787 Rome, 1871). The writing took the form of the theoretical manifesto of what would, to all intents and purposes, go down in history as the Purist movement. Bianchini, who spoke explicitly about what the term “purism” meant and what the origins of this “reform” of art were, rejected one by one all the objections that academic circles made to the purists. To the accusation of “recopying nature miserably and continually with every defect,” Bianchini responded by saying that the purists “seek the severe, simple, evident demonstration of the things represented, that is, of the subbie of painting,” and since man cannot attain perfection, “they estimate that the least defect should be put before them, which is to aspire to the end by means that are not very delightful in themselves, but effective.” To those who accused the purists “of wanting adult painting to revert to Cimabue’s dolling,” Bianchini retorted by asserting that it was obviously not their intention to learn from the primitives the way of drawing, coloring and combining planes, but rather to look to them for their rendering of affect and their ability to express the artist’s deepest feelings. To the artifices of modern art, the purists therefore responded by preferring "the crude simplicity of the ancients." And to the accusation that they wanted to reject art from Roman Raphael onward, Bianchini opposed the desire to speak to the soul, rather than to amaze with the viewer by putting the message in second place to the “exterior beauty of the means”: something that, according to the purists, would characterize the works of the mature Renaissance.

Lorenzo Bartolini’s L’Ammostatore represented, in 1818, an isolated case, ahead of its time and debates: all the more valuable, therefore, does the work appear to us if we think of how innovative and original it was, to the point that many scholars recognize in it the moment in which purism began. Called the “first example of naturalistic renewal on the neoclassical strain” in the catalog of the 1972 exhibition, curated by Sandra Pinto, on neoclassical culture in Grand Ducal Tuscany, a sculpture that boasted “chronological precedence” vis-Ã -vis other purist experiences according to Ettore Spalletti, and still a “turning point work” according to Stefano Grandesso, theAmmostatore is the naturalistic image of a boy crushing grapes in a bigoncio in order to obtain must from them. Caught in a contrapposto pose, he holds a few bunches of grapes with his right hand, while his left hand casually rests on his hip, creating a sort of triangle. The head is animated by a slight twist that, in order to introduce a motion of further naturalness, interrupts the fixity that would have resulted from a rigidly frontal pose: it is a gesture that fully captures the soul of the subject and makes him emotionally alive, a detail that alone would be enough to differentiate theAmmostatore from much of neoclassical sculpture.

Obviously, Bartolini’s young man is also distinguished from the entire neoclassical production by the reference models, all drawn from the early Florentine Renaissance, which the Prato sculptor must have been well aware of. Long is the list of those who have pointed to a derivation of theAmmostatore from Verrocchio ’s David (Florence, c. 1435 - Venice, 1488), which has the upper limbs in the same position as those of Bartolini’s Harvester and is animated by the same twisting of the head, with the muscles of the neck in tension. Others have noted theAmmostatore ’s proximity to another model, the 1430 David by Donatello (Florence, 1386 - 1466), while a further cue can be found in a fresco that Benozzo Gozzoli (Scandicci, c. 1420 Pistoia 1497) executed in the Monumental Cemetery in Pisa: in particular, in the scene of the Grape Harvest and intoxication of Noah we see a man who, like Lorenzo Bartolini’s youth, is intent on crushing grapes in a chariot quite similar to the one the 19th-century sculptor imagined for his work. The precise desire to refer to early Renaissance precedents constituted a notable break with neoclassical sculpture: if the latter went in search of ideal beauty, purism pursued natural beauty instead, and early Renaissance artists were seen by purists as those who, in their quest, were animated by a desire to refer to nature rather than to pursue an ideal of beauty.

| <img src=’https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2017/746/david-donatello-verrocchio.jpg’ alt=“Right: David by Donatello. Left: David del <a href=”https://www.finestresullarte.info/arte-base/andrea-del-verrocchio-vita-opere-maestro-leonardo-da-vinci“>Verrocchio</a>” title=“Right: David di Donatello. Left: David del Verrocchio.” /> |

| Right: Donatello, David with the Head of Goliath (c. 1430-1440; bronze, height 158 cm; Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello). Left: Andrea del Verrocchio, David with the Head of Goliath (c. 1475; bronze, height 126 cm; Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello) |

|

| Benozzo Gozzoli, Vendemmia ed ebbrezza di Noè (1468-1484; fresco; Pisa, Camposanto) |

All these features did not escape the notice of those who had a chance to see Bartolini’s work at the time of the creation of the version for Count Tosio Martinengo. Among them was the man of letters Pietro Giordani (Piacenza, 1774 Parma, 1848), who already in the 1920s, at the time when he had had the opportunity to see Lorenzo Bartolini’s Carità educatrice and to express his enthusiasm in a letter sent to Leopoldo Cicognara, had well grasped the spirit of the Pratese, and had described him as a “sculptor always and only intent on the natural,” who “has become accustomed to seeing and representing it with the eyes and soul that made the school of Donatello dear to the world.” On August 1, 1844, Giordani wrote to a friend, the Greek-born Venetian Count Antonio Papadopoli, that he had seen Bartolini’s “little Bacchus” in Milan, and outlined it in these terms: “it is a real delight to those who contemplate it (and they are many, and they are not satiated); it is an amazement to artists : who well know how difficult and rare it is to represent with such full evidence a real, and such a real so finely chosen and studied; of a garzonetto of about twelve years old, delicate and veracious to the possible; all intent (and a little fatigued) in the work of mingling.” It was the face that was the detail that had most caught Giordani’s attention: “well made the vivid eyes, in the beautiful mouth a principle of a smile, as of an amiable contented little person. And whoever thinks that the movement of smiling in sincere persons begins from one of the sides of the mouth, is not surprised that the line of this mouth appears not exactly parallel with the other two upper lines of the face.” And again, “all graceful contours, suave skin, pleasing gracefulness of the neck, arms, hands: all a beauty, and beauty all proper to those tender years in a delicate shapeliness.” Giordani went on to praise the young man’s study of anatomy, admirable in its ability to avoid transcending the real, but also not to “dirty the beautiful,” also reporting how many who had seen the work thought as he did and went so far as to say that “from the time of Phidias to this Christian year 1844 very few sculptures can stand comparison with this one for iscience and good judgment of statuary anatomy.” Above all, the Emilian scholar grasped the principle that had animated Bartolini’s research and that the sculptor from Prato continued to forcefully affirm in his Ammostatore: “thus with work of purgatory design, of vivid signification, overcoming all ordinary and extraordinary difficulties, the supreme artist visibly confirms his dogma, that only in truth is beauty, of universal and eternal beauty: thus he condemns anyone who presumes to add fantastic beauties to nature.”

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, The Ammostatore, detail of bust |

|

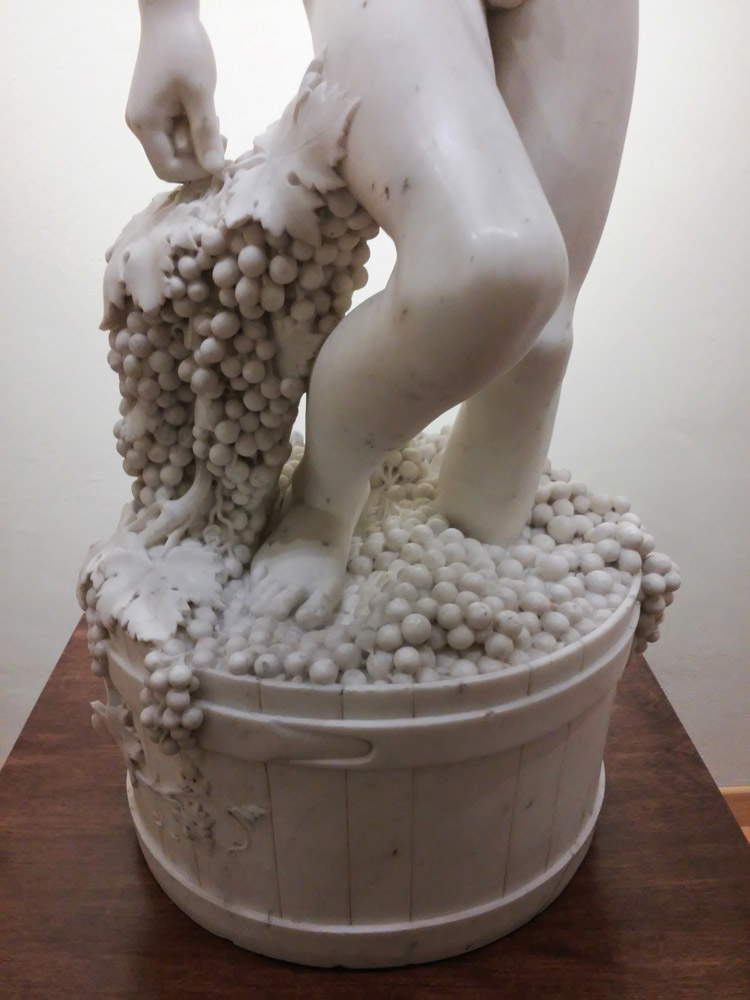

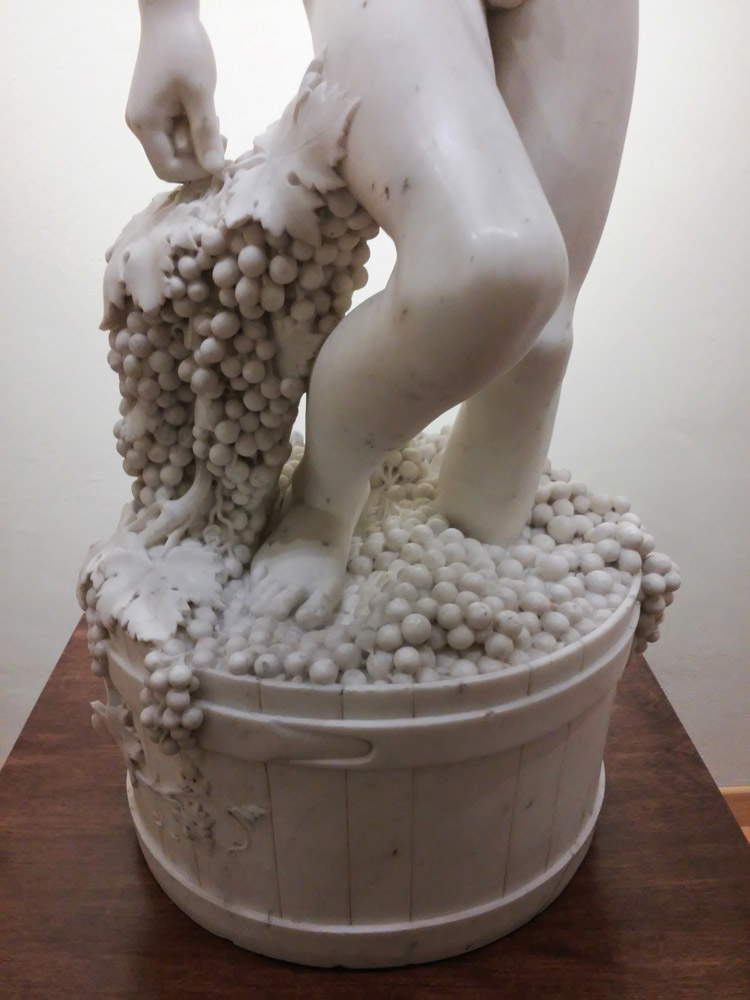

| Lorenzo Bartolini, The Ammostatore, detail of the legs |

|

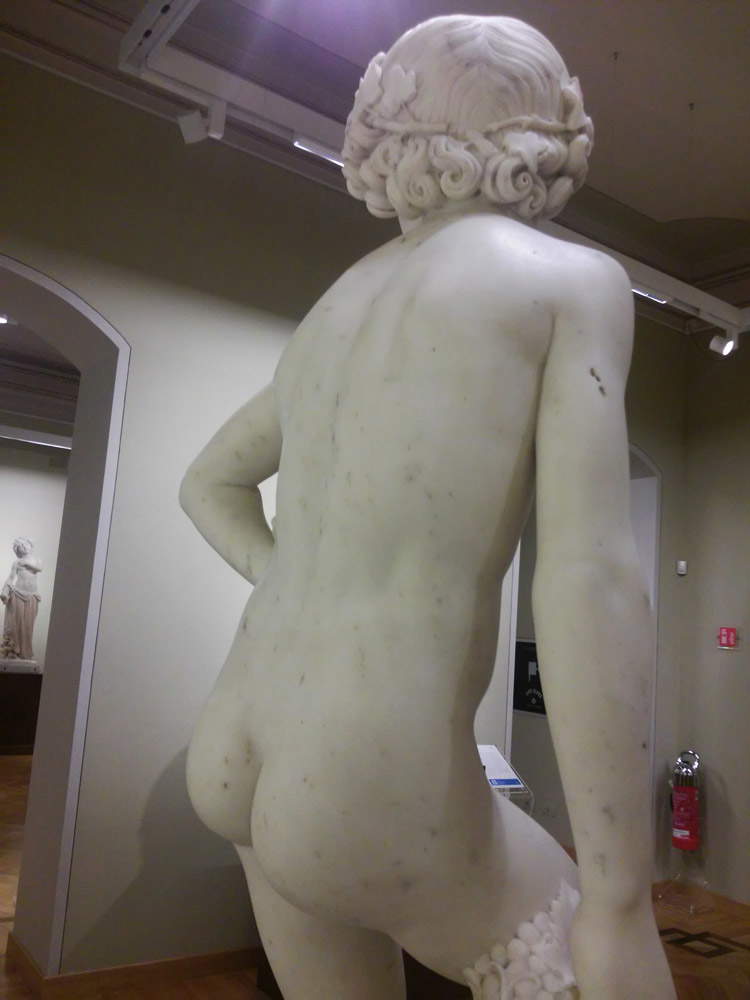

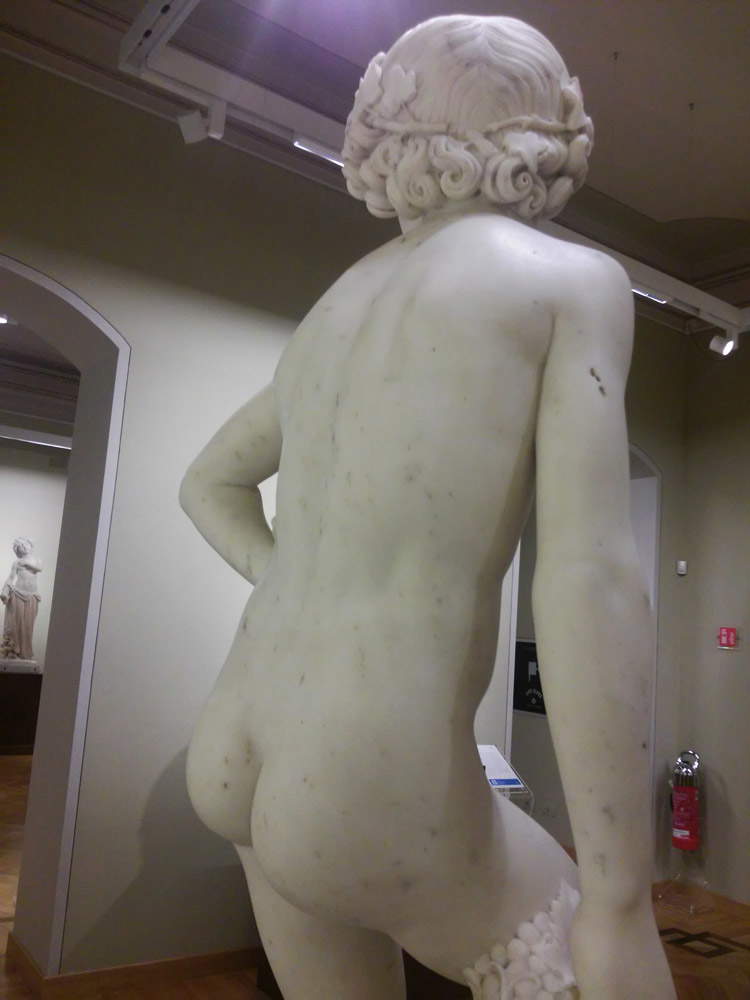

| Lorenzo Bartolini, The Ammostatore, side view |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, The Ammostatore, detail of the back |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, The Ammostatore, detail of the chariot |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, L’Ammostatore, detail of the grapes |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, L’Ammostatore, detail of the grapes |

The work, which received considerable critical acclaim and was hailed as a manifesto of purist poetics, stood as a lofty example of the natural beauty that, according to artists who wanted to break free from neoclassicism, should animate artistic research. A fundamental work, therefore, in the path of Lorenzo Bartolini, present in several exhibitions that have aimed to investigate not only his art (think of the great monographic exhibition Lorenzo Bartolini. Sculptor of Natural Beauty held at the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence in 2011), but also the developments of art from Canova onwards: it could not therefore be missing from the Carraresi exhibition Dopo Canova, one of the most effective in outlining the paths taken by art once the neoclassical experience had moved towards its conclusion. Finally, this is one of the rarest and happiest sculptures produced by Lorenzo Bartolini’s chisel, so much so that the writer Paolo Emiliani Giudici, in an article in the magazine Il Crepuscolo, called it “a statue of exquisite beauty, from which Bartolini’s glory truly begins.”

Reference bibliography

- Sergej Androsov, Massimo Bertozzi, Ettore Spalletti, After Canova. Paths of Sculpture in Florence and Rome, exhibition catalog (Carrara, Palazzo Cucchiari, July 8-October 22, 2017), Fondazione Giorgio Conti, 2017

- Sergej Androsov (ed.), Canova at the court of the tsars: masterpieces from the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, exhibition catalog (Milan, Palazzo Reale, February 23 - June 2, 2008), 24 Ore Cultura, 2008

- Carlo Sisi, Ettore Spalletti (eds.), In the Sign of Ingres. Luigi Mussini and the Academy in Europe, exhibition catalog (Siena, Santa Maria della Scala, October 6, 2007 - January 6, 2008), Silvana Editoriale, 2007

- Stefano Grandesso, Sculpture. From More Roman Classicism to Romantic Sculpture in Carlo Sisi (ed.), LOttocento in Italia. The sister arts. Il Romanticismo 1815-1848, Mondadori Electa, 2006

- Ettore Spalletti, Nature, style and thought in the work of Lorenzo Bartolini in Antonio Paolucci (ed.), Palazzo degli Alberti. Le collezioni d’arte della Cariprato, Skira, 2005

- Paola Barocchi, Modern History of Art in Italy. Manifestos, Controversies, Documents. Vol. 1: From Neoclassical to Purist 1780-1861, Einaudi, 1998

- Sandra Pinto, Ettore Spalletti, Lorenzo Bartolini: exhibition of conservation activities, exhibition catalog (Prato, Palazzo Pretorio, February - May 1978), Centro Di, 1978

- Sandra Pinto (ed.), Neoclassical and Romantic Culture in Grand Ducal Tuscany. Lorraine Collections, Later Acquisitions, Deposits, exhibition catalog (Florence, Palazzo Pitti, 1972), Centro Di, 1972

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.