Longing for Africa. African art and the avant-garde

Since ancient times, cultural contaminations and appropriations have distinguished the confrontation and clash between different communities, involving the most diverse fields of human knowledge, from language to writing, from cultivation techniques to navigation, from crafts to warfare, and so on. Dialogue and interaction between different artistic cultures also connotes a large number of experiences scattered along the multi-millennial parabola of art history. Among them, beginning in the early 20th century, loaded with implications was the impact of tribal art on modernist artists. It was a phenomenon of enormous scope, the understanding of which even today is complicated by a plurality of definitions and interpretations. The term “tribal art” would like to gather within it the art typical of African, Oceanic, and Native American peoples. Also variously referred to as primitive art, although the criticism has long been advanced that this term is Eurocentric and derogatory, it was embraced in its formal aspects by European avant-garde artists, giving rise to the phenomenon of primitivism. However, in the prejudice of an art that in the eyes of Europeans had as its glue being a naive, immediate art, far from the corruptions of modern civilization and tradition, Egyptian art, and even all the arts considered non-classical, that is, prior to the mature Renaissance, also ended up with little discernment. But European arts, however archaic and anti-classical, did not have the same exotic value. For this reason, not infrequently, to the already labile terms anticipated, “ethnographic art,” “indigenous” or art nègre could also be found as synonyms.

Although the advance of this phenomenon has gone hand in hand with the progress of ethnological sciences, it could not therefore be further from philological rigor. It is particularly with African art, charged with mystical and atavistic values, that European art of this period incurred the greatest debt. The interest in the varied art coming from this boundless continent is accompanied by a well-known and abused founding myth: around 1906, the painter Maurice de Vlaminck is said to have bought an African sculpture at a market, which he proudly showed to André Derain, telling him, “It is almost as beautiful as the Venus de Milo.” The painter friend, on the other hand, would reply that that work was “as beautiful as” the famous statue: they then decided to settle the dispute by presenting the African work to Picasso, who would lapidarily conclude “even more beautiful.” True or alleged, this anecdote shows with extraordinary immediacy how, within a generation, what had been one of the most admired and copied works was surpassed by an African work. But how had such an abrupt change in tastes and patterns been possible?

The encounter with African art (although it would be more accurate to speak of ethnographic artifacts) is not exclusive Beginning in the early 20th century, laden with implications was the impact of tribal art on 20th-century modernist artists: already over the centuries some objects had entered European collections. But at the end of the 19th century an innumerable quantity of artifacts also flowed into Europe thanks to a new interest in ethnography, which proceeded hand in hand with the colonial enterprises of the great powers. Contextually, the Universal Expos had allowed new possibilities for encounters with the craftsmanship of non-Western cultures, which likewise entered ethnographic museums. From there on, African art would be the focus of exhibitions and even traded by art dealers such as Joseph Brummer and Paul Guillaume, later entering prestigious collections such as that of the Russian ŠÄukin.

Artists moving into the early 20th century thus found multiple possibilities for comparison, and in African art they discerned some solutions to plastic, formal, and expressive problems that the modernist avant-garde had placed at the center of its research. The ground, moreover, had previously been beaten on the one hand by Gauguin, who had marked his artistic experience with a continuous search for primitive and uncorrupted forms, seeking references in non-Western art, and on the other by the research around volumetric synthesis carried on by Cézanne. The two great artists were being rediscovered in 1906 and 1907, respectively, thanks to two major retrospectives devoted to them at the Salon d’Automne.

In addition to the episode triggered by Vlaminck, there are numerous personalities who have claimed credit for having “discovered” African art, but the work that famously enshrines the beginning of this new trend is Pablo Picasso’s celebrated painting Les demoiselles d’Avignon. In June 1907 Picasso decided to modify the large painting that was already well advanced, transforming the two figures on the right, initially conducted like the others in the style inferred from archaic Iberian sculptures, taking for inspiration the tribal art he had been able to admire at the Trocadero Ethnographic Museum. Picasso’s desire was to break with the narrative framework to propose an iconic register: the dark deformity of the masks created a short-circuit within the painting, between the carnal sinuosity of the Iberian figures and the gloominess of the two African figures, with the desire to evoke the personification of “pure sexual energy,” a life force capable of lowering us into an “orgiastic dimension,” as critic Steinberg reviewed.

Picasso, more than any other artist, declines in his works the lesson inferred from African art, experimenting from painting to polymateric sculpture. His affinity for this art was such that there was even a widespread myth that he had some African ancestry, which came to him through Moorish Hispanic blood. In the same year as Picasso’s famous painting, André Derain made the first version of Bathers, strongly related to the Spaniard’s work. The French painter, a passionate collector of art nègre, and Henri Matisse, fulfilled their desire for simplification and plastic synthesis through the formal solutions of primitive art. Matisse, in the Portrait of Madame Matisse, makes his wife’s face as if it were “a mask,” noted André Salmon, with definite references to the Fang or Shira-Puru masks of Gabon.

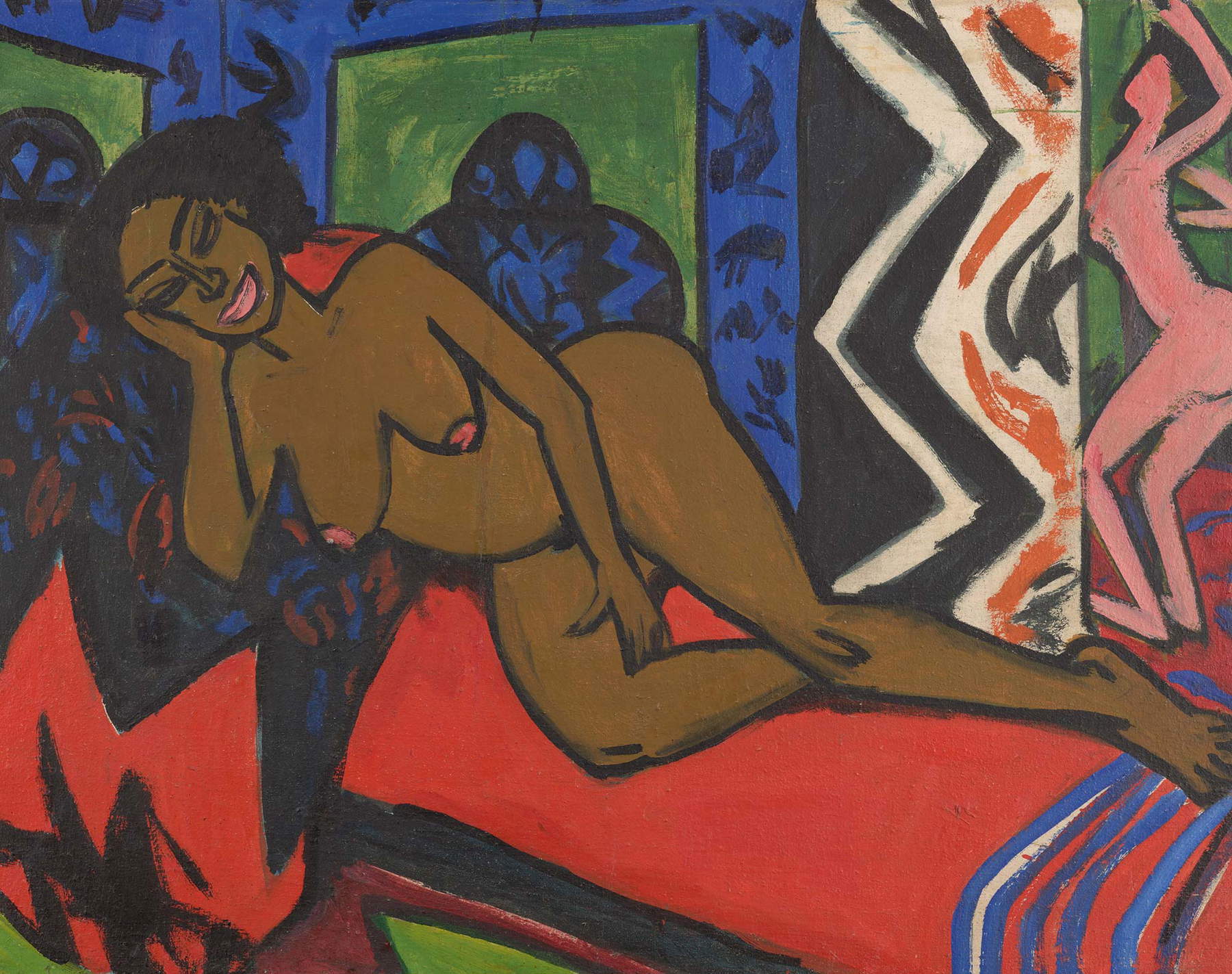

European avant-garde artists thus drew from African finds solutions to their questions in art, combining them with the possibility of performing a nonconformist, anti-bourgeois act. More often than not, these were mere formal filiations, but other artists contracted an undoubtedly more complex debt, such that they were able to assert multiple levels of interpretation. Picasso had shown the ritual and cathartic power that masks had: “they were not sculptures like any other, but magical objects” created by intercessors. This approach also characterizes German expressionism: members of Die Brücke assimilate the vital and brutal power of these ancestral forms to exasperate their painted figures, deformed to the limit of the grotesque and charged with a wild and dramatic spirit.

Other artists prefer an approach devoid of emotionality, opting for a logical formal reading, interested in the opportunities for volumetric and plastic simplifications, setting the construction on an overall harmony, or drawing ideographic solutions. This is the case of sculptor Constantin BrâncuÛi, who in tribal art finds some plastic-structural solutions for his works, as in Adam and Eve of 1921, where African influence is refracted in the structure composed of vertical superimpositions, and in the physiognomy of Eve. BrâncuÛi does not give a mystical, dark reading, but states that there is “joy in Negro sculpture.”

If not joy, at least harmony and sinuosity are the traits that Amedeo Modigliani, a friend of the Romanian sculptor, inferred from African tribal art. For the Leghorn artist, acknowledging the debt to this art is no easy feat, since it coexists with an innumerable amount of different contributions and influences, first and foremost that of Egyptian art. And it is precisely Modigliani who becomes an advocate of a muted and tempered comparison with African art, an aestheticizing approach that is echoed in the development of the plastic approach played out in a counterpoint of solids and voids, in the clarity and essential linearity, in the search for stylization and synthesis, and in the organic way of understanding reality. Modigliani, seemingly without making distinctions, approached the extra-Western and European primitive arts, in which he sought not only exquisitely formal responses but also archaic values, almost out of time, in an absolute attempt at a dialogue with eternity. We could say that Modigliani elevated primitive art, nevertheless making a distinction and selecting only that which matched his refined sensibility, alongside classical art, which continued to be an indispensable reference for him. One can speak of genuine classicist primitivism.

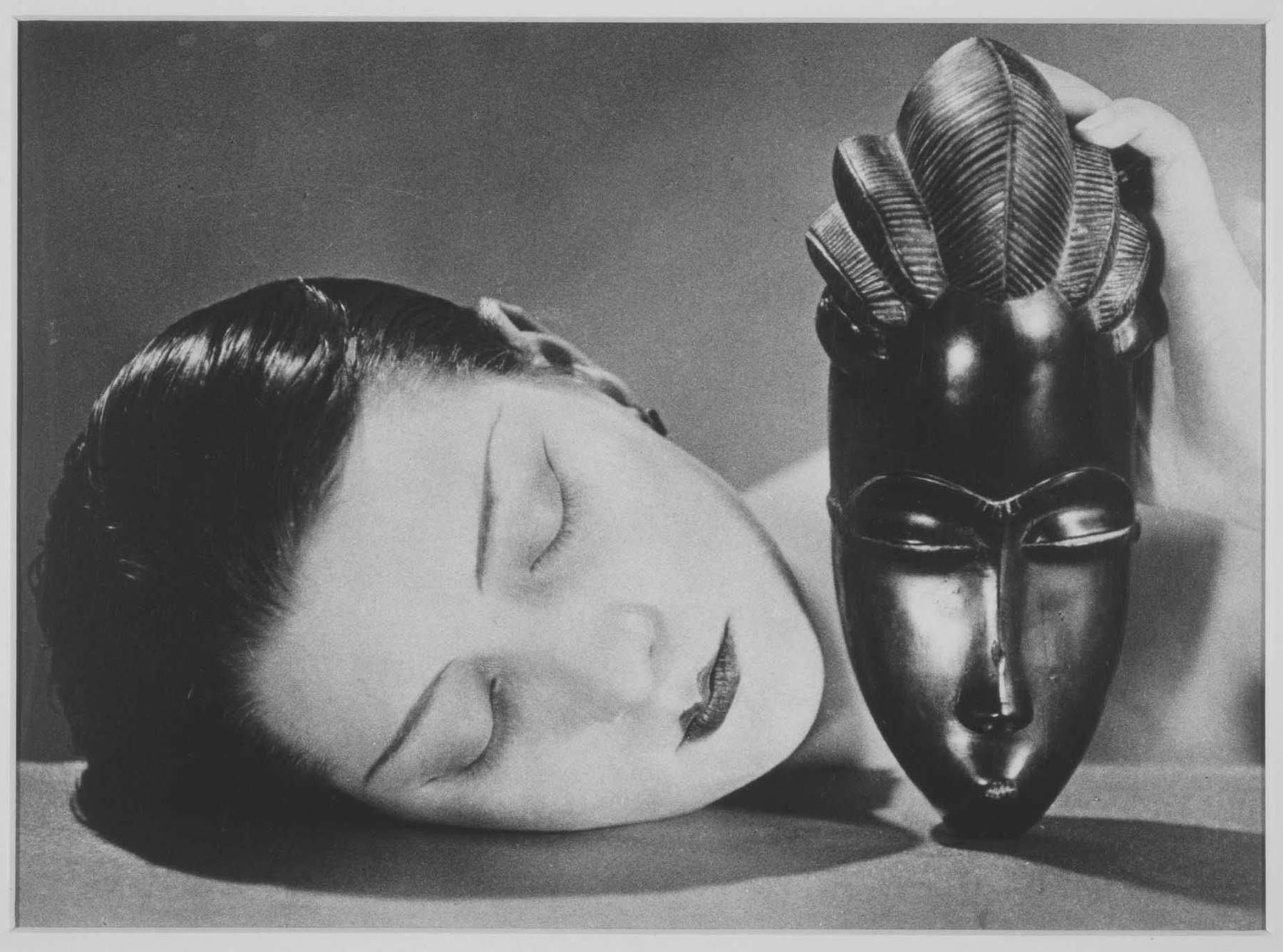

Slightly at the antipodes, on the other hand, is the approach that would later lead the Surrealist cohort to confront African art. The Surrealists gave it a dreamlike reading that was based on the belief that it had not been contaminated by reason, but rather possessed an expressive freedom dictated by the unconscious or hallucinatory state. This interest takes very different forms: the ancestral handwriting in paintings born of the automatisms of André Masson; the archetypal masks of Marx Ernest, strikingly similar to the Tusyan masks of the Upper Volta; Alberto Giacometti’s Nose in dialogue with the Baning masks of New Britain; the primal energies of Paul Klee’s work, to Man Ray’s photographs such as Noire et blanche, where the famous Kiki of Montparnasse is portrayed in her pale whiteness in contrast to a Baoulé mask, typical of the Ivory Coast.

From the Surrealist lesson, the confrontation with African art would also become, to a certain extent, the heritage of the avant-gardes that would inaugurate the second half of the century, such as the Informal movement, and would also be felt overseas by the Abstract Expressionists, testifying to how the encounter and confrontation with African art had a preponderant weight in the artistic poetics of a good part of the 20th century.

However, it should again be pointed out how this dialogue is characterized as an eminently ethnocentric and unidirectional phenomenon, since it projects Western expectations, interests, and value models onto products of other cultures, often trivializing their reading. Deprived of their original function, arriving to artists mutilated and incomplete or through serial copies created for the Western market, prejudicially loaded with the myth of being created by an anonymous artist, these artifacts had been decontextualized from the beginning. Picasso himself stated, “Everything I need to know about Africa is inherent in that object.” In this hierarchical relationship, African production became a rich aesthetic repertoire, and confrontation with it an exercise of the European artist to sharpen his own Western awareness. After all, the very idea of being confronted with art objects is the result of a Eurocentric conception, of which Marcel Duchamp was keenly aware: in a conversation with Pierre Cabane who argued that there were no societies without art, the Frenchman had responded by stating that those who made wooden spoons in the jungle of the Congo had not done so for the Congolese to admire them, and neither were fetishes and masks intended for such a purpose, even if the Europeans had forced it upon them. After all, Duchamp concluded, it is we who “have created art for our exclusive use: it belongs to the sphere of masturbation.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.