Like Andy Warhol's Flowers. Lightness versus what is ephemeral

We live in a world of porous and unstable boundaries, in which everything seems to ruefully slip out of our hands in the name of a destiny that cannot be completely controlled. Everything cracks and at times inexorably breaks every certainty of our cognitive schemata, and we are deprived of that cozy conviction in which everything is inscribed within clear boundaries, in which no one is left behind and locked in his or her own solitude. This is why we tend, very often, to go through the tangled webs of life feeling alone in our strange uniqueness, as if no space is allowed for some people. The world in which we live runs fast and seems to have no time for the last, for those who come later and do not immediately meet society’s standards.

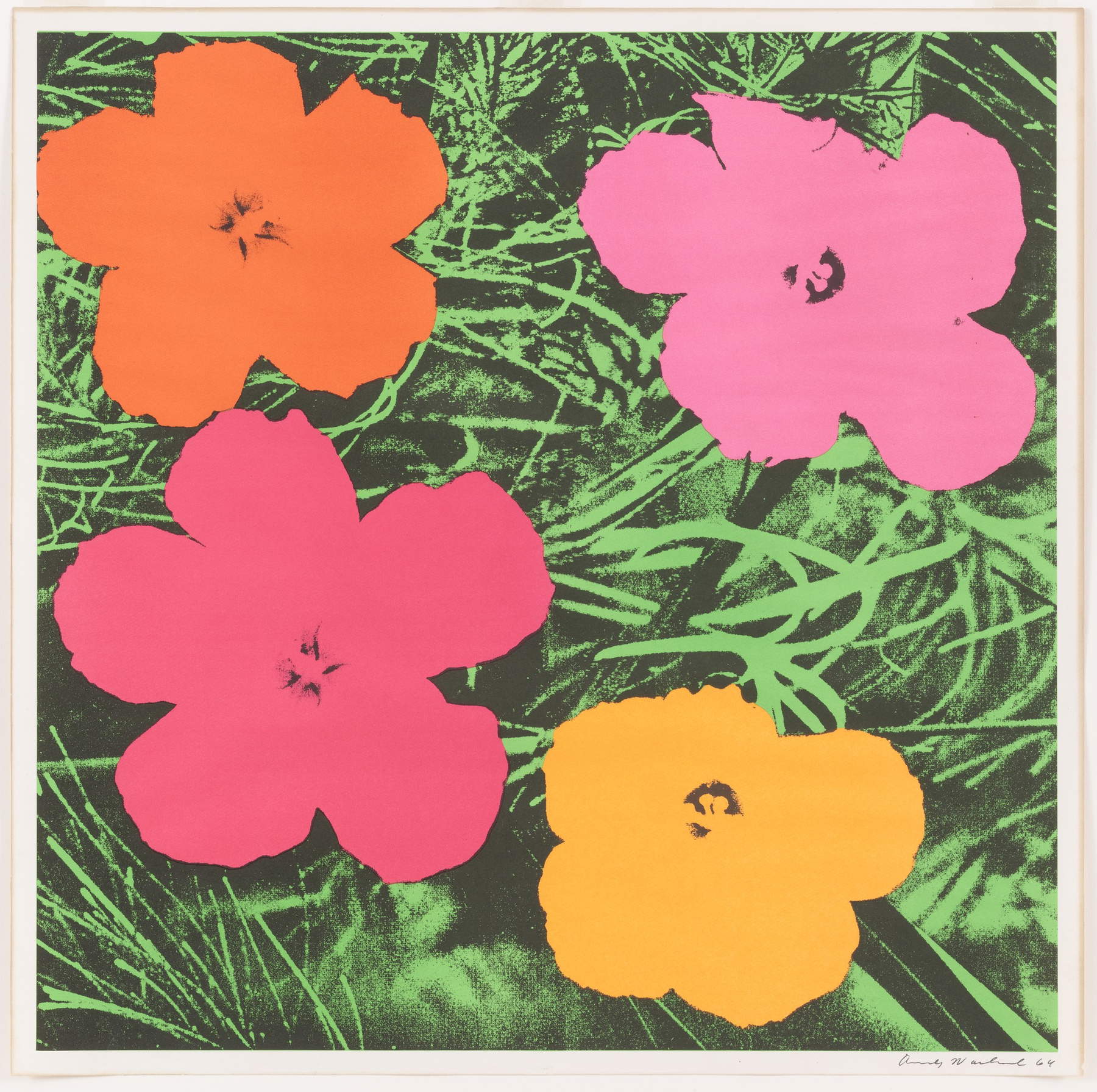

Andy Warhol ’s works speak of this very thing. They tell the viewer about a constant push for something fast, immediate. They remind us, screamingly, that we belong to the society of consumption, of everything immediately, of conformity and deep loneliness. It would be as anachronistic as it would be incautious to want to draw a posthumous psychological profile of an artist in these spaces, but often art and its protagonists can be very useful in shedding light on an uncertain future and can help trace faint geographies starting precisely from the past. And this is also what a serial artwork such as Andy Warhol’s Flowers from 1964 tries to tell.

In 1962 the artist began experimenting with a new technique that would be the turning point of his production and, therefore, of his career. He invented a new printing system, called photoserigraphy, made from a black-and-white photograph and the use of inks or colors and subsequent duplication on canvas. “In August ’62,” Warhol recounts, “I began making silkscreens. The rubber mold method I had used up to that time to repeat images suddenly seemed too homemade; I wanted something stronger that would make more of an assembly line. In screen printing, you take a photograph, enlarge it, transfer it to silk by shielding it with glue, and then ink it, so that the ink seeps through the silk but not through the glue. In this way you get the same image each time slightly different.” He began to apply this technique by turning images of stars and consumer objects into works of art, and works of art into consumer objects elevated to stars.

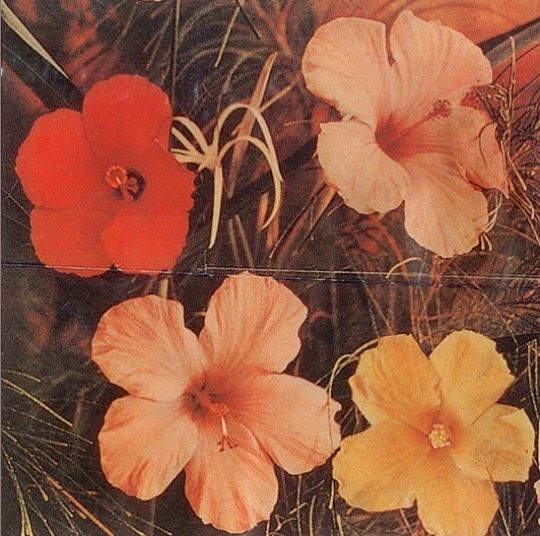

Flowers of 1964 is an acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas painting for which the artist starts with a color photograph of hibiscus flowers taken by Patricia Caulfield and published in Modern Photography magazine in June of that same 1964. Warhol adapts the image, cropping and distorting it, transforming it and making it purely graphic. He reiterates the same photograph over and over again, telling of a hasty, consumerist world, elevating obsessive repetition to art. His experiments aimed at seriality, at fast production that chases a frenetic and tight rhythm, the same rhythm that was intent on New York with its consumer society and from the restless and constant momentum toward the future. And so the artist appropriatesimages that are simple, direct and, in a way, extremely didactic, and above all, without any personal touch except solely for the randomness that contributes to their emergence.

Warhol’s works will never be the same precisely because different unforeseen external factors intervene at the press, all those smears typical of existing become embodied on the canvas. And so thanks to too much or too little ink, the ever-changing color, the canvas stretched more or less, the pressure heavy or excessively light, these little contingencies create new and ever-changing works.

The 1964 canvas depicts four white flowers, a symbol of purity and fragility, silhouetted against a dark background with violent blades of grass of a very acid green. The work, belonging to the Schulhof collection, is located on the ground floor of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice on a white wall. Mrs. Hannelore B. Schulhof, who lived in Germany until the outbreak of World War II, was a huge art lover along with her husband, Rudolph B. Schulhof, whom she married in Brussels until they decided to move to the United States where they began their collecting business.

Hannelore and Rudolph Schulhof shared Peggy Guggenheim’s belief that they should collect as many works of the time in which they lived and so they created a most delicate collection of European and American art after World War II. It was out of this mutual respect that the couple decided to donate, upon their death, their collection to the world-famous museum in Venice. A donation consisting of 83 works from Warhol to Anish Kapoor via Dubuffet. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation is thus a collection of collections whose works mirror the sensibilities of individual collectors. Each with its own history and its own crazy artistic loves.

The first Flowers were created by the artist in 1964 in New York, during an exhibition in Leo Castelli’s gallery. The entire exhibition space was flooded with colorful flowers, and the garden made of canvases and prints filled every room. The obsessive repetition was a success and all the works sold. It was a seemingly simpler and more innocuous image than previous ones like the Campbell Soup, but it contained another meaning. The work was a denunciation, a warning against all that is ephemeral and fleeting. A white flower, a symbol of fragility par excellence, becomes eternal through the genius of the boy from Pittsburgh. Perhaps this, as indeed almost all of his poetics, is an allusion to the nagging relationship between life and death.

Indeed, the artist had a childhood marked by illnesses that affected normal physical development: scarlet fever at age eight, then rheumatic fever that evolved into a central nervous system disorder and subsequent hand tremors with an inability to write on the blackboard. Art critic Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, about this eccentric artist wrote “Warhol’s work is a descent into hell that lasts an eternity. He comes to tell us: forget all the meanings that in the layering of time have been attributed to man’s existence on earth. He comes to tell us: make a clean slate. [...] He does not offer us solutions, he does not even give us Ariadne’s thread to get out of the labyrinth. Because there at that point his task is finished. The atomic bomb explodes before your eyes one two three four thirty times; man commits suicide one two three six times....”

Warhol is part of the outcasts, the misfits, those who would like to find a space in the world by which they are constantly devoured, torn to shreds and spit back out with no chance of salvation. Death is at the center of his poetics and worldview. His work is a colossal and theatrical memento mori that is not poeticized, but raw and real. His death asks to be seen simply for what it is, the end of a story. The American artist does not need to depict pain exposed and dramatized, sometimes four flowers are enough, and to remove blood and flesh Warhol uses precisely the mechanical process. Warhol observes everything, takes everything because everything can be mere surface, everything can be art. He was torn between two parts of his personality: one more fragile and the other irrepressibly eager to become famous. In doing so he dies and is reborn again and again, he becomes a chameleon-like transformer who adapts to change to mask his insecurities. Her strength is drawing, her unpredictability is printing, and her uniqueness is the very inauthenticity of her artwork.

Reading through the pages of Andy’s life we understand, more than ever before, that we are social beings and that this deeply internalized sociality is fueled by our most mundane lives and experiences. We wake up and are drawn into a constant back-and-forth of relationships, things, places, forgettable exchanges and, as psychoanalyst Vittorio Lingiardi explains, all of this contributes to the “physical and mental passage that is part of our history as it is realized so far and that unconsciously gives us a sense of identity and belonging.” As a teenager, Warhol was not interested in the groups of winning kids, he was not interested in being liked at any cost, but he wanted to be popular and easily fit into the group of “different ones.”

Marcel Proust in the third volume of In Search of Lost Time wrote, “All that we have that is great comes to us from the nervous ones: it is they, and not others, who founded religions and created masterpieces. Never will the world know how much it owes them, and especially how much they suffered to produce it. We enjoy delicate music, beautiful paintings, and a thousand exquisites; but we do not know how much they have cost, to the creators, of insomniacs, epilepsies; and that terror of death which is the worst and which you may know, madam.” Andy Warhol belonged to those nervous people who were always too much, but never enough. He was so engulfed by the fear of public speaking that he ended up memorizing a script and reiterating it, as he did his art. He was a fragile, isolated, insecure, vulnerable man, but he knew where he wanted to go and how to get there.

He understood, as only an artist can, that life is ephemeral illusion and that the loss of identity in a world where every individual has to run faster than others to be somebody is the real fear that grips this world. He understood that each of us carries on our own very personal fiction of self. And perhaps that is precisely why for his epitaph he said, “I always thought I would like to have a grave with nothing, no epitaph, no name. In fact no, I would like them to write on it: fiction.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.