With his painting, Claudio Olivieri sought to give form to the invisible. One could summarize in this way, certainly trivializing but giving back a glaring and effective image, much of the research of the great Roman artist by birth, Mantuan by adoption, Milanese by training and cosmopolitan by culture, among the major exponents of Italian analytical painting and not only, although the artist himself felt any categorization as narrow and inadequate. He was in any case one of the most consistent and constant artists of the second half of the twentieth century. The Glory of the Invisible, Light of the Invisible, Ungraspable Light, Visible Infinity: these are the titles of some of Claudio Olivieri’s exhibitions that have taken place in recent years. Infinito visibile is the first exhibition to be held after the artist’s passing in 2019: in Mantua, the city of his mother, in the ground-floor rooms of the Ducal Palace, the Claudio Olivieri Archive has made a selection of works from the beginnings to the extreme phases of his activity to give an account of the unique, free, and original path of an artist who, we read in the apparatus accompanying theaccompanying the exhibition, has found terms of comparison on all continents, keeping up to date with the results of the German “Geplante Malerei,” the American “Post-Painterly Abstraction,” and even “Dansaekhwa,” the monochrome painting (that’s what the term means) that emerged in South Korea in the 1970s, and the experiences of the Japanese Mono-Ha group.

What is the invisible for Claudio Olivieri? Meanwhile, it is literally what lies beyond the visible. This may sound like a paradox: a painting that tries to show what cannot be seen, what lies beyond the senses. However, there is also a “seeing without origin,” according to the artist, and painting is the tool that gives substance to these visions that are not grounded in a tangible reality, although they never fully transcend the perceived. The invisible is a dimension beyond the phenomenal: within the invisible there is history, there is memory, there is myth, there are memories, there is the imagined, therethere is thought, there is in essence a reality that is even wider and more surprising than what can be touched with the senses. “It is with painting that appearances are changed into apparitions: what is shown is not verisimilitude but birth,” the artist explained in one of the thoughts that Matteo Galbiati brought together in a volume, Del resto, containing an anthology of Olivieri’s writings and published in 2018. And it is for these reasons that the titles of Claudio Olivieri’s works take on such evocative titles, linked to visions, dreams, stories, characters, and philosophical concepts: Metempsychosis, Hera, Vanishing, Extreme, Finally, At Risk, Burning Byzantium. One can well understand how Olivieri’s urgency is therefore very concrete, so much so that painting is a very physical thing for him. The absolute that he seeks with his works is indeed “something elusive, something that cannot be encoded in an image, something that cannot be fixed on a material support,” Silvia Pegoraro recalled on the occasion of an exhibition of Claudio Olivieri held in 2002 at the Casa del Mantegna in Mantua, but the substance that makes it emerge is alive. And as a result, Olivieri wanted to “imprint the painting with infinity, welcoming the changing essence of light,” explained Matteo Galbiati in an article published in Espoarte a few months after the artist’s passing. A light that is always alive, palpitating. Physical and present. Because painting, Olivieri himself explained, “is also body, physicality, presence.”

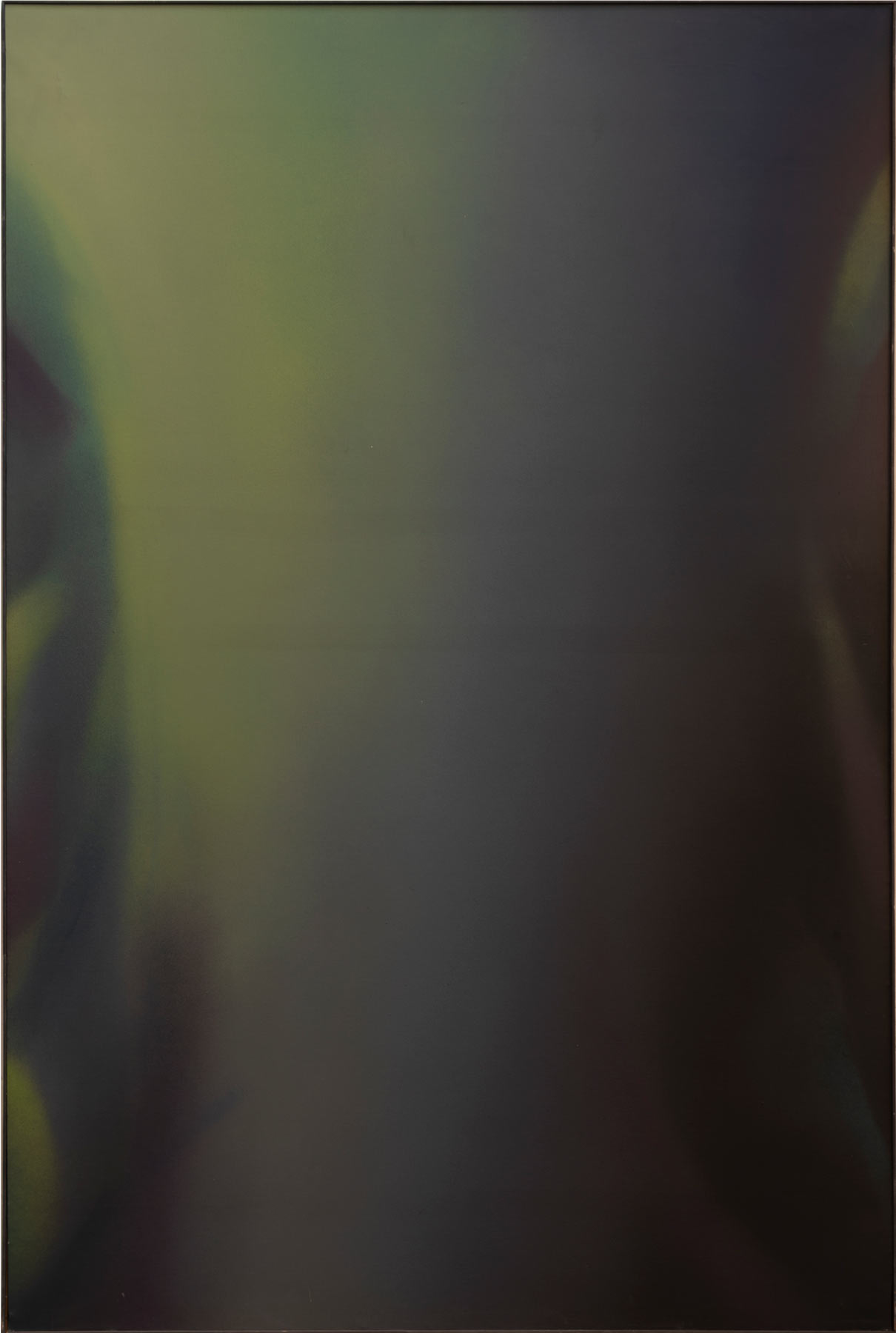

This is why light is the medium by which Olivieri gives form to the infinite, to the invisible. Delicate light that dances elegantly on the surface of the canvas creating “chromatic curtains” that, wrote Giorgio Di Genova in his Storia dell’arte italiana del ’900, “move faintly like veils to the breath of the breeze”: the critic cited 1983’s Barlume as one of the paintings most illustrative of Claudio Olivieri’s poetics. Faint light that, in this painting, reveals itself almost hesitantly, light that rains down gently from above without investing the entire surface, light that lingers, creating glimmers that appear gradually, variations of green, a glimmer that takes to spreading shyly. In other paintings by Claudio Olivieri, the light is, on the contrary, more stubborn and peremptory, more on and intrusive, in others it is almost completely off, sometimes the luminous blades arrive solitary, sometimes they appear in pairs, rising or falling, almost always vertically, as happens in Barlume. The chromatic traces impressed by the light are “indices of the elsewhere,” as Giorgio Verzotti has effectively defined them.

This unveiling of the invisible, the result of that “lucid and suffered inquiry into the infinitude of space and the mutability of light” (thus Fabrizio D’Amico in the introduction toan exhibition by Claudio Olivieri at Galerie 21 in Livorno) that has always characterized his research, takes place before the eyes of the relative with a painting that is not only evocative, not only transports the viewer to a distant and other dimension, but is also extremely meticulous. After an early career characterized by works that were almost instinctive and much more material than those that would later mark the continuation of his career, from the 1970s onward Olivieri constructed his images with calibrated stratifications of colors, spread with the airbrush (although he would later not give up the brush or even the rag anyway) in homogeneous backgrounds to obtain veils, luminous bands, halos of different entities that arrange themselves around a point of origin, sometimes becoming denser, or receding, creating different planes of depth, appearing and disappearing within fascinating light movements that register the traces of infinity, capture a part of it, show it to the observer. In Barlume, for example, the invisible manifests itself for a moment and then disappears again, amidst the light sloping toward darkness being, however, revived at the end by a final glow.

It will be interesting to recall that at the Infinite Visible exhibition, in the autumn, on clear mornings, from the windows of the rooms of the Ducal Palace where the spaces of “LaGalleria,” the museum’s space reserved for contemporary art exhibitions, were created, it was possible to see a few rays of sunlight filtering through the grates and resting on the paintings. Branches of the infinite and the unseen interacted surprisingly and unconsciously with Olivieri’s painting, enhancing its quality, emphasizing the virtuosity of his technique. And becoming further interpreters of its meanings.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.