"Libiamo, libiamo ne' lieti calici": the disruptive power of Bacchic dances.

“Run, O Mènads, run, O Mènads,[...] amidst phrygian songs, amidst cries, while from the sacred harmonious flute vibrate sacred melodies that guide those who to the mount hurl themselves. And agile as a filly through the fields free, follows the Mènade, and to dance drives the agile foot” (Euripides, Bacchae).

The animated words with which the first semi-chorus introduces in Euripides’ well-known tragedy the figure of the Maenads (better known, in “Roman jargon,” as Bacchae) well explicate the uniqueness of the followers of Dionysus. God of wine, drunkenness and the most natural and wild animal instinct, the son of Zeus and Semèle, known in Roman religion as Bacchus, best represents the blazing, frenzied germ of life that, boundlessly, pervades everything.

It is again Euripides who, in the course of the narration of his own tragedy, giving the floor to the principal performers (Cadmus and old Tiresias above all), manifests how the central attribute in the dynamics of Bacchic rites is, in a very striking way, dance. “Dancing, we alone in Thebes, the Bacchic dances?”, “If we alone are wise, and foolish the rest.” The excited dialogue between Cadmus, the former, and Tiresias, the latter, gives an account of how the incomparable vitality of the “Bacchic festivals,” in addition to the ever-present and iconic attribute of wine, revolved precisely around the unbridled animosity and rhythmic gestures of the bodies.

The legend, perhaps among the richest and most articulate in the entire mythology, sees Dionysus being born in Thebes from the secret union between Zeus and Semèle who, instigated by the jealous Hera, asked to be allowed to admire Zeus in his dazzling power. This induced request cost her her life since, surrounded by thunder, lightning and flames generated by kings of Olympus, the daughter of Cadmus died enveloped in divine fire. Despite the unfortunate occurrence, Zeus rescued the still premature offspring from the woman’s womb, causing its gestation to end in her thigh. Entrusted later to Hermes, Dionysus, cared for by the nymphs, grew up on Mount Nisa, a high ground full of lush forests and located in ancient Thrace: hence the epithet “Zeus of Nisia.”

Reaching adulthood, Dionysus discovered the vine plant and learned its cultivation until he was totally intoxicated by its divine fruits, which he promptly made known to his nurturers as well. Enchanted as well by the suave goodness of the grapes, Dionysus, crowned with ivy, began to wander with them through the lands of the Balkan peninsula followed by a numerous procession of dancing Nymphs and Satyrs.

Although some critics identify ancient Thrace as the origin of Dionysian rites, the cult of the deity found with certainty its origin in Ellas beginning in the 6th century B.C. and then gradually spread throughout the territories of Magna Graecia. The spread of the ancestral rites along the coasts of the Italic peninsula is narrated by Livy in his famous Ab Urbe condita. In fact, the historian specifies in Book XXXIX how the germ of the unbridled vitality of the Dionysian festivals was introduced to Rome at the hands of the Campanian priestess Anna Paculla. The excessive lasciviousness and lustfulness of ritual (which began to involve women and men indiscriminately), resulting from concurrent dances animated by a natural primal instinct, came to take root overwhelmingly in the Urbe by the second century B.C., creating no small amount of disarray and disappointment among the local population.

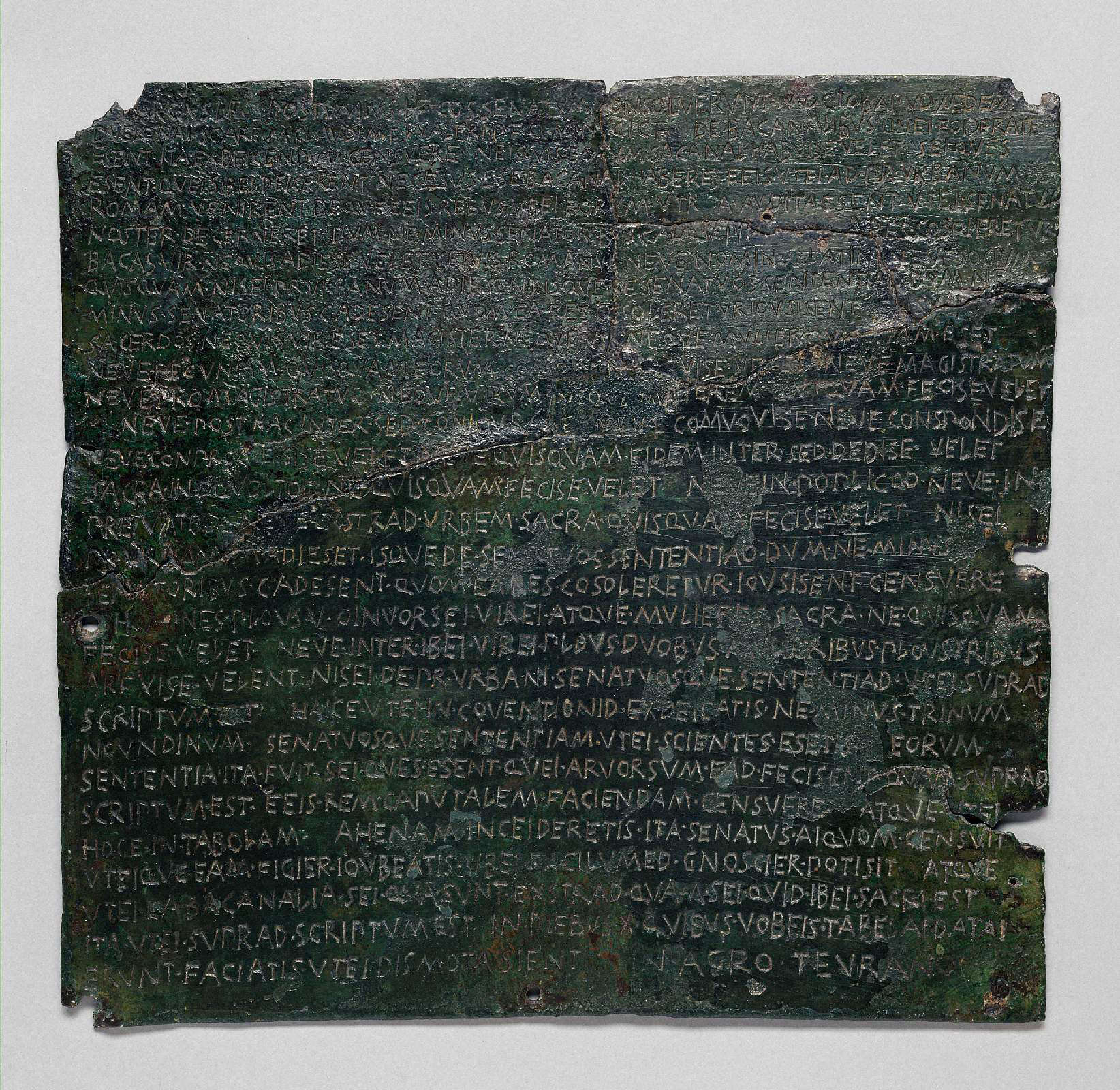

The spread of the cult of Dionysus (now known under the name of Bacchus), a rite not indigenous to and distant from the Roman mores, led the Senate to issue, in 186 B.C., a decree called Senatus consultum de Bacchanilibus, through which the practice of Bacchanalia was officially banned along the entire Roman territory. It appears of considerable interest to point out that, a copy of this decree, now preserved at the Kunsthistorisches in Vienna, was found in 1640 in Tiriolo (Catanzaro), during excavations for the building of the palace of Prince Giovanni Battista Cigala.

The growing popularity of the Bacchanalia involved, inevitably, also the figurative arts, which since as far back as the 6th century B.C. tried to bring back the “dancing” vitality of the Maenads with extreme correspondence to the truth.

Numerous and manifold are in the Archaic age those artifacts whose decoration refers to the Dionysian festivities, as well testified by the Promonos Vase, an Attic crater now preserved at the MANN, or by the later House of the Procession of Dionysus, which, built in the Antonian age at El Jem, in present-day Tunisia, presents a refined mosaic depicting the animated Dionysian procession.

But Bacchic animosity, which can be declined and investigated under multiple facets, turned out to be a particularly suitable theme, and one proposed, from the 16th century onward, when reflection on the “line,” the study of anatomical rendering and the attempt to investigate the real datum, became characteristics decidedly suitable and corresponding to such a narrative. An early example that well explicates the declination of the theme is found in The Arrival of Bacchus on the Island of Naxos , a work attributed to Giovanni Luteri, better known to the chronicle as Dosso Dossi.

Growing up in what is now the Lombard town of San Giovanni Del Dosso, the name from which Lauteri derives his nickname, the artist matured in those lands on the border between the Marquisate of Mantua and the Duchy of Este. Although biographical information about Lauteri’s youthful education is still unclear today, it certainly cannot be ruled out that he grew up studying Lorenzo Costa (the Gonzaga’s artist after Mantegna’s departure) and that, appointed court painter to the Este family (1514), he did not observe the painting of Giorgione and Titian, as well as the ubiquitous Raphael, during his Venetian and Florentine sojourns.

The arrival of Bacchus in fact presents all the pictorial influences indicated and, with absolute probability, can be placed within a prestigious commission such as that for Alfonso I d’Este, duke of Ferrara, who for his Camerino dei Baccanali commissioned the likes of Giovanni Bellini(The Banquet of the Gods) and Titian, works centered precisely on the festive Bacchic theme. And it will be Vecellio himself who will “stage” one of the most famous, iconic and influential canvases in his production as well as in the entire history of art: the Bacchanal of the Andrii.

The canvas, in fact, constitutes the last element of a triad that, along with the Bacchus and Ariadne at the National in London and the Feast of Cupids, now in the Prado, disrupted the entire art scene on the peninsula. Titian’s Bacchanal embodies better than any other work the unbridled vitality of “Dionysian” rituals: to the left of the scene, a softly shaped man drinks wine straight from the pitcher with undeniable vehemence; in the center, placidly reclining figures converse with one another not caring, as the maiden in the foreground demonstrates, what is being poured into their plates; in the right margin, a sensual female figure, partially covered by exquisite white drapery, appears at the complete mercy of life’s pleasures.

But what is more striking than anything else turns out to be the group of men with their heads girded with laurel who, captivated by the suave beauty of the young woman, engage in an energetic dance witnessed, even more, by the shimmering, rippling draperies that well manifest the intrinsic and animated vitality of the rituals, as well as of the scene. The work, following the Devolution of Ferrara (1598), was brought (or rather taken) to Rome by Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini, and this arrival, due to the innovative uniqueness of the artistic language coined by Titian, is considered by critics to be one of the fundamental steps in the development of Baroque language in Rome.

The Urbe, in fact, at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, thanks to the enlightened “modernization” initiated by Sixtus V (1585-1590), was emerging as the new European artistic center, replacing Venice, which in the sixteenth century had played an absolute leading role in the European scene. Into this lively cultural climate came, in 1594, the coming to Rome of Annibale Carracci, who, commissioned by Odoardo Farnese, frescoed one of the most famous works of the artist’s production: The Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne. The scene, animated by that explicit desire to abandon the stale Mannerist language at the expense of a deeper investigation of the real, punctuates the vault of the gallery by proposing (in the wake of a spatial orchestration recalling classical friezes) a narrative where the dancing dynamics of Bacchic processions are even more explicit.

During the first two decades of the seventeenth century Rome, for artistic centrality, also attests to the presence of Nicolas Poussin. The French artist, attracted by the fervent cultural climate and, above all, by the opportunity to take advantage of the rich local private commissions, arrived in the Urbe in 1624 and here, with more than considerable probability, he must have observed the Titian Bacchanalia . It is certainly no coincidence that in 1625-1626 is ascribed a work that, preserved today at the Prado, is inspired by Vecellio’s famous work: the Madrid Bacchanal , in fact, although based on the revival of that classical matrix so dear to Poussin and clearly visible in the spatial orchestration of the scene, takes up the natural and wooded architectural background adopted - frequently - by the Venetian master himself. The narrative, punctuated by the rhythmic gestures of the characters, is animated by a continuous dancing procession that, however, unlike Titian’s work, does not present any “fragmentation” or solution of continuity.

The Bacchanalia theme continued to be addressed throughout the 18th century, as evidenced by an exceptional and refined canvas by Sebastiano Ricci. The Bacchanalia in honor of Pan, at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, fully manifests the detailed vivacity of the Belluno artist’s pictorial language, whose modus pingendi lends itself well to a type of narrative where rhythm, vitality, playfulness and licentiousness turn out to be peculiar and essential aspects.

The painting, which is characterized by a very detailed graphic attention-above and beyond well evident in the rendering of the landscape elements-reserves a central role for the frenetic dances of the Bacchae who, not surprisingly, stand out at the center of the narrative “assisted” in the dance by an eager faun. All around, musicians, playing putti, lovingly outstretched figures embody even more Bacchic festivity.

The theme continued to be tackled again during the 18th century as evidenced by Francesco Zuccarelli’s pleasing canvas, also preserved in the Gallerie dell’Accademia. The Tuscan artist, between the 1840s and 1850s, staged his Bacchanal in a suave and idyllic bucolic landscape, emblematic of the “Classical Ideal” now sought by the artists of the time.

The narrative, set in a context where the description of floral and faunal elements while seemingly marginal contributes in no small part to a complete rendering of the whole, still sees as its central focus the theme of animated dancing: the painting, while abandoning that aura of ancestral bacchic atmosphere, manifested in the previous century, maintains through a more compassed and “classical” description that lively and dancing file rouge resulting from the meeting of the charming maidens with the fauns.

The Bacchanalim therefore, to the rhythm of music and dance have accompanied us since antiquity and testify to how human beings, when free from restrictions and constraints, can consider themselves, thanks to their innate primordial instinct, a true social animal.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.