Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man: history and meaning of a modern design

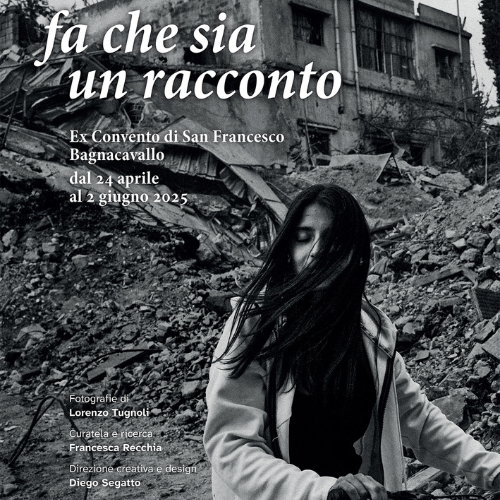

“Vetruvius architect puts in his work of architecture that the measurements of homo are of nature disstributed in this way. That is, that 4 diti makes a palm and 4 palms makes a foot; 6 palms makes a cubit, 4 cubits makes a homo, and 4 cubits makes a step, and 24 palms makes a homo; and cqueste misura son in his edifizi. If you open your legs so much that you chalk them from chapo 1/14 of your height, and open and raise your arms so much that with your long fingers you touch the line of the top of the chapo, know that the cientro of the stremita of the open limbs will be the bellicho. E llo spatio che ssi truova infra lle gambe fia triangolo equilatero.” These are the words with which Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) opens the description of the very famous Vitruvian Man, in the five lines found at the top of the sheet preserved in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice. But what exactly is the significance of this drawing, and for what reasons is it so important that it is considered one of the symbols of the Renaissance? What we see drawn on the sheet is a human body inscribed in a circle and a square: this was not a Leonardo invention.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, The Proportions of the Human Body According to Vitruvius - “Vitruvian Man” (ca. 1490; metal point, pen and ink, touches of watercolor on white paper, 34.4 x 24.5 cm; Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia) |

The story of one of the world’s most famous designs begins inancient Rome, and to be precise toward the end of the first century B.C., when a celebrated architectural theorist of the time, Marcus Vitruvius Pollonius (c. 80 B.C.-20 B.C.), wrote the treatise that would consign his name to history: the De architectura, a work in ten books in which the author offers a comprehensive overview of the art of architecture. In the third book, devoted to temples, Vitruvius says that there can be no temple that is not governed by principles of harmony, order, and proportion among the various parts of the building. The same is true of the human body: “without symmetry and without proportion no temple can exist that is endowed with good composition,” Vitruvius writes (the translation from Latin is ours), “and the same is true of the exact harmony of the limbs of a well-proportioned man.” Vitruvius uses the expression homo bene figuratus, “well-proportioned man”: such he will be only if the measurements of the parts of his body correspond to precise canons. Vitruvius also takes care to identify a canon, the same one mentioned by Leonardo in his description of drawing. Thus, for Vitruvius, the head represents one-eighth of the human body, the foot one-sixth, the cubit (i.e., the forearm) one-fourth, the chest also one-fourth, and the center of the human body is to be found in the navel: “if a man were placed supine, with hands and feet spread out, and a compass were placed in his navel, the circle drawn would touch the fingers and toes. And just as it is possible to inscribe a body in a circle, in the same way it is possible to inscribe it in a square: if the measurement is taken from the feet to the top of the head and the same measurement is related to that of the outstretched arms, the height will be equal to the width, just as it is in the square.” Pliny the Elder (Como, 23 - Stabia, 79) is said to have come to the same conclusions, writing in his Naturalis historia that “it was observed that the distance in a man from the feet to the top of the head is the same as that between the fingers of the hands with outstretched arms.”

The fact that Pliny also devotes a few lines to this subject is a detail of no small importance: his Naturalis historia is translated by the great humanist Cristoforo Landino between 1472 and 1474, and the translation would have been published in Venice in three different editions (1476, 1481 and 1489). We know for a fact that Leonardo possessed a copy of this translation: it is therefore possible to assume that the genius from Vinci had come into contact with the Vitruvian canon through Pliny’s mediation. What is certain is that, in the same years, Vitruvius’ treatise became the object of special attention by artists and humanists. In 1450, Leon Battista Alberti, in writing his De re aedificatoria, had also taken up the ten-book structure of the De architectura, and a few years later (between 1461 and 1464) Filarete would also draw important suggestions from Vitruvius’ writing for his Treatise on Architecture. If the first printed edition of De architectura, edited by Giovanni Sulpicio Verulano, probably dates back to 1486 (or at any rate to a year not later than 1490), more or less to the same period it is possible to date the first vernacular translation, by the works of a versatile genius such as Francesco di Giorgio Martini (Siena, 1439 - 1501), who devoted many years of work to the work, with continuous revisions and updates (for some scholars the translation, contained in the Codex Magliabechiano now preserved at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence, is finished in 1487, while for others it would be several years later). Interestingly, in 1490, Leonardo and Francesco di Giorgio had met in Milan and Pavia: on both occasions the two worked in the cathedrals of the two cities. The mutual exchanges between these great artists (like Leonardo, Francesco di Giorgio is also a painter, writer, architect, and engineer) are still the subject of study but, knowing the two, we can certainly say that the meeting must have been particularly significant.

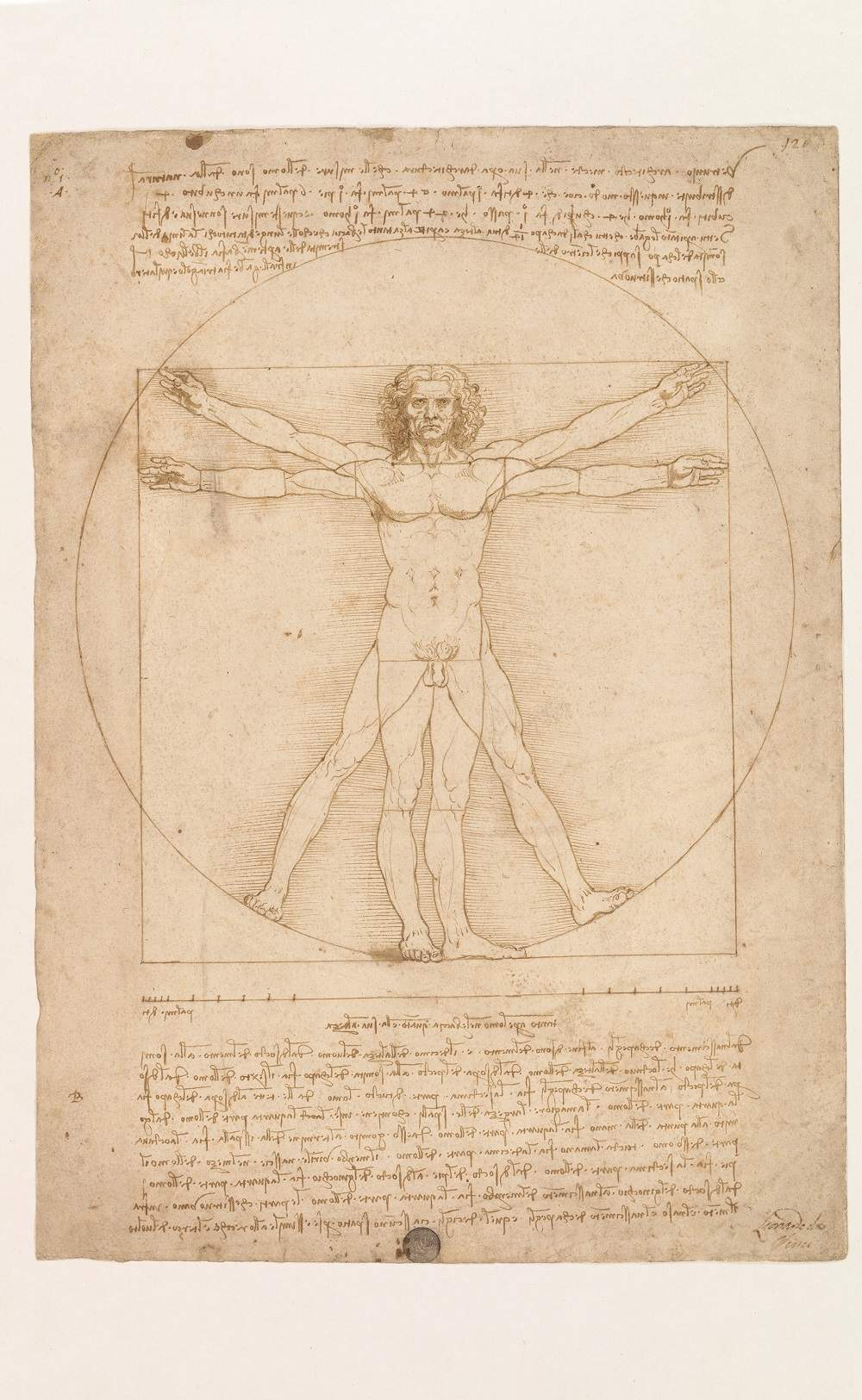

The two artists are linked by, among other things, a common attempt to offer a graphic representation of the Vitruvian canon. Of course, neither Leonardo nor Francesco is entitled to primacy: the first representation of a man inscribed in a circle is older, and can be found in the work of a Sienese engineer who lived between the end of the 14th century and the first half of the 15th century, Mariano di Jacopo known as Taccola (Siena, 1381 - 1453/1458), who between 1419 and 1450 had worked on an important engineering treatise, De ingeneis. In the manuscript we find, precisely, an illustration in which we observe a man, with his arms stretched out along his sides, in a standing position, whose feet and head touch the ends of a circle, within which a square is inscribed. We do not know whether Leonardo knew this drawing (it is instead likely that Francesco di Giorgio did), but it is nonetheless a work that has different assumptions than the more modern one Leonardo made some seventy years later (and we will soon see why).

|

| Mariano di Jacopo known as Taccola, Proportions of the Human Body, from De ingeneis (c. 1420; ink on paper, 30 x 22 cm; Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm. 197, fol. 36v) |

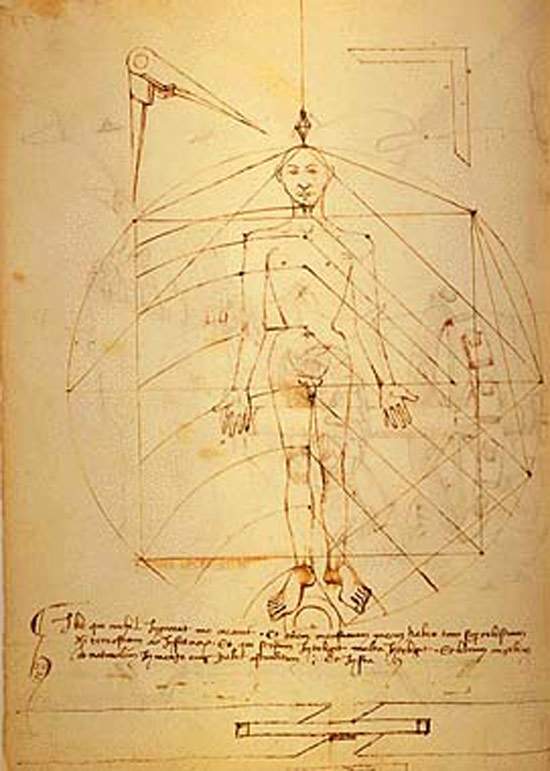

In fact, Leonardo’sVitruvian Man dates to a year around 1490: interestingly, Francesco di Giorgio, at the same time (or, in all likelihood, even a few years earlier) had also proposed his own solution to the problem of inscribing the human body in the circle and square, with a drawing used in his Treatise on Architecture, dated by most critics to sometime between 1481 and 1484. Leonardo and Francesco’s drawings diverge, however, in very profound ways. Francis draws the figure so that the circle and the square are superimposed, so that the height of the man inscribed within them corresponds to both the side of the square and the diameter of the circle. In this way, however, the Vitruvian assumption that the navel should be the center of the body would be undermined: in Francis’ drawing, as is evident, it appears slightly off-center upward. It should also be noted that Francesco di Giorgio’s man fails, with his left hand, to touch the corresponding side of the square. Instead, Leonardo proposes a different solution: the exact center of the circle this time is the navel, as Vitruvius suggested, but the square and the circle do not share the same center. Leonardo, in contrast to Francesco di Giorgio who had depicted his man in a single position, namely standing, opts instead for two different poses: one in which the man is depicted standing and with his arms outstretched, so that his height and the width of his arms correspond to the sides of the square, and one in which he is supine, with his arms and legs spread apart, touching at four different points the circumference of the circle.

|

| Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Interpretation of Vitruvian Man," detail (c. 1480; ink on paper, 38.5 x 26.5 cm; Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, cod. Ashb. 361 fol. 5r) |

Leonardo’s solution appears, therefore, as the finest graphic representation of the Vitruvian canon. It is conceivable that Leonardo arrived at his design independently of the efforts made by Francesco di Giorgio: he probably benefited from his colleague’s translations, as well as from the cues that, we can imagine, Francesco provided him with during their meeting (and, in turn, the genius from Siena would have derived many useful suggestions for his Treatise on Architecture from his brief association with Leonardo), but theVitruvian Man is also the result of original experimentation. The proportions of the figure, in fact, are not exactly those reported by Vitruvius: Leonardo, in his description of the drawing, introduces some additions and modifications. For Leonardo, for example, the foot would correspond to a seventh of the man’s height (instead of a sixth as Vitruvius claimed), and the measurement from the sole of the foot to the knee would constitute a quarter of the height (an indication not found in Vitruvius). These are signs that Leonardo does not intend to follow the Vitruvian canon to the letter, but intends to provide, through the empirical experimentation that has always been constant in his method (and which reveals all the modernity of this great genius), a model that, while looking to tradition (which, in any case, comes mediated to Leonardo, who does not know Latin, or has very vague knowledge of it), is new and up-to-date.

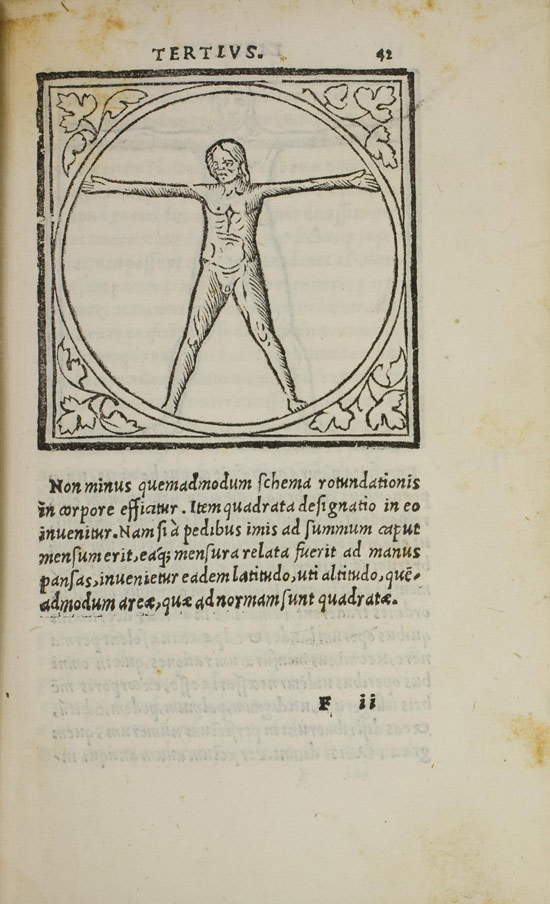

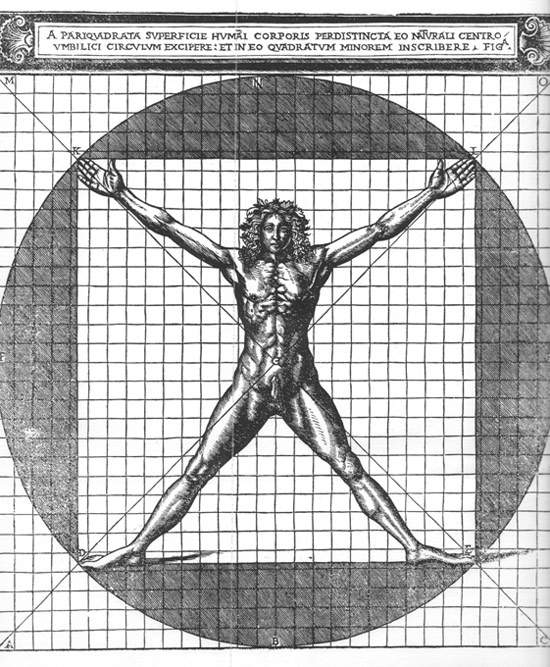

Leonardo is neither the first, as we have seen, nor, much less, the last artist to grapple with the Vitruvian canon. It will therefore be worth mentioning three other authors who wanted to measure themselves against the proportions indicated by the great Roman architectural theorist. The first is Fra’ Giocondo da Verona (Verona, c. 1534 - Rome, 1515), editor of the first printed edition of Vitruvius’ De architectura equipped with illustrations, published in 1513. The Venetian humanist, in contrast to Leonardo, uses two figures to demonstrate Vitruvius’ ideas: in one, we find man inside a circle (which, in turn, is inscribed in a square, as was the case in Francesco di Giorgio’s drawing), with arms and legs spread apart, while in the second illustration the man is standing in a square, with his arms outstretched to touch the two sides. In contrast, the first printed edition of the Italian translation of De architectura, edited by Cesare Cesariano (Milan, 1475 - 1543), dates from 1521. His illustration is one of the most curious interpretations of the Vitruvian man. The scheme changes further from those of Leonardo, Francesco di Giorgio, and Fra’ Giocondo, and is related to that of Taccola (although it is entirely likely that Cesariano did not know the Sienese architect): the square is therefore inscribed in the circle. The man we find in Cesariano’s book stretches out his arms and legs diagonally so that his hands and feet touch at the same time the corners of the square and four different points on the circumference, with his navel acting as the center of both the square, as it is at the exact intersection of the two diagonals, and the circle. The illustration, the idea for which is nevertheless attributed by Cesariano to a nobleman named Pietro Paolo Segazone (about whom we know very little, however), does not, however, have the same modernity and coherence as Leonardo’s, albeit about thirty years later: in order to adapt the pose of the body to the figures, Cesariano in fact had to disproportionately deform the size of the hands, thus contravening the Vitruvian canon itself. A further novelty introduced by Cesariano is the well-erect penis, which has been variously interpreted, but it could be an attempt to reconcile the two centers of Leonardo’s depictions, with the member pointing toward the navel: in fact, if we look at the man inscribed in the square in Leonardo’s drawing, we notice how the center of the figure falls at the height of the penis. However, symbolic interpretations should not be ruled out a priori, and perhaps the idea of attributing the idea of the depiction to the now-unknown Segazone could be an expedient that Cesariano used to avoid tedious fuss. Finally, it is worth mentioning the Vitruvian man by Giacomo Andrea da Ferrara, a friend of Leonardo’s, who in a manuscript now preserved at the Ariostea Library in Ferrara draws a man inscribed in a structure identical to Leonardo’s: with all evidence there were contacts between the two (and perhaps Giacomo Andrea, who knew Latin, may have been helpful to Leonardo in understanding the meaning of the Vitruvian text), but we do not know exactly how and in what manner they took place.

|

| Fra’ Giocondo da Verona, Homo ad circulum et ad quadratum, (1513; printed volume, 17 x 11 cm; Milan, Castello Sforzesco, Ente Raccolta Vinciana) |

|

| Fra’ Giocondo da Verona, Homo ad quadratum, (1513; printed volume, 17 x 11 cm; Milan, Castello Sforzesco, Ente Raccolta Vinciana) |

|

| Cesare Cesariano, Homo ad circulum et ad quadratum, (1521; printed volume, 37.2 x 25.1 cm; Milan, Castello Sforzesco, Ente Raccolta Vinciana) |

But let us return to Leonardo’s drawing. In order to understand its significance, it may be interesting to start from a passage by Manfredo Tafuri, who wrote as follows in 1978: “In this drawing we visualize the microcosm of man, a theme dear to the Platonic and Neoplatonic tradition, in relation to the order of the cosmos and to that created ex novo by architecture.” The artists who had grappled with the Vitruvian canon did not only intend to solve problems of a practical nature, that is, to provide canons for measurement (let us not forget that in ancient times the units of measurement were parts of the human body: the foot, the cubit, the palm ), or defining the correct proportions for the representation of man in painting and sculpture and relating them, in architecture, to the proportions of buildings: attempts to satisfy the Vitruvian canon also had important symbolic implications. That man was a “microcosm” was an idea also reported by Leonardo himself, who in one of his writings expresses himself in this way: “l’omo è detto dalli antiqui mondo minore.” It is a theory that, as Leonardo explains, had originated in the ancient world: however, it had known many interpreters in all ages, up to the Renaissance. Underlying the various declinations of the so-called theory of the microcosm was the belief that man was a reflection of a higher order, almost an entity that bears within itself the elements that make up the whole world.

The circle and the square must therefore be read symbolically, partly on the basis of Christian reinterpretations of the microcosm theory: the circle would be an allusion to the divine sphere, while the square would represent the earthly world. Man, halfway between divine and earthly, would be a connecting element capable of uniting the two worlds. Thus, the first attempts to inscribe man in a perfectly superimposable circle and square should be read in this sense. We said that Taccola’s Vitruvian man was moved by different assumptions than Leonardo’s: in fact, Mariano di Jacopo was still bound to this way of understanding man. It was, we might say, a kind of mixture of humanism and Christianity that, while drawing on the tradition of the ancients, still identified man as the image of God (and, consequently, even buildings constructed in relation to the measurements of the human body were to be considered almost as a manifestation of the divine will). This way of thinking is well exemplified by the commentary that appears underneath Taccola’s Vitruvian man and which, translated from Latin, means, “He who ignores nothing created me. And I bear in me every measure: both those of heaven, and those of earth, and those of the underworld. And he who understands himself has in his mind many things, and has in his mind the book of angels and of nature.” The man who is inscribed in the circle and the square is thus the creature capable of bringing heaven and earth into harmony.

However, in Leonardo, as we have seen, square and circle appear misaligned: therefore, the symbolic intentions discussed above are lost. Illuminating appears, in this sense, the interpretation of Leonardo’sVitruvian Man offered by a great Austrian art historian, Fritz Saxl. For Saxl it is necessary to start from a fundamental assumption: Vitruvius’ De architectura had become a book of basic importance for Renaissance aesthetics. And since it is in this book that we find the idea that man can be inscribed in a circle and a square, “Leonardo’s drawing,” says Saxl, “must not be seen as a representation of the microcosm.” Quite simply, “it is a study of proportions.” It should be pointed out that this is an interpretation at odds with others who instead also read Leonardo’s drawing in terms of a depiction of man as a microcosm, but at this point it is interesting to refer to what another art historian, Massimo Mussini, points out about the figure of Leonardo, starting precisely from Saxl’s interpretation. If we look at the drawing, we can see that, in the figure of the standing man, inscribed in the square, vertical and horizontal marks appear. There are several of them: at the height of the hands, knees, pubis, shoulders, all along the chest. These are the marks through which Leonardo wanted to bring back the proportions discussed in his “introduction” to the drawing. For Mussini, the fact that the artist reported them in thehomo ad quadratum, instead of thehomo ad circulum, takes on an important significance. The image inscribed in the square is in fact the one Leonardo refers to “when he reports Vitruvius’ proportional canon, which is precisely segmentation of the unity of the microcosm, its preliminary decomposition into parts to initiate the process of scientific knowledge that is accomplished through the use of the senses guided by mathematical instruments.”

The human body, in essence “becomes a measure, becomes the object of painting (which for Leonardo is an instrument of knowledge based on analytical observation of the natural) that comes to reconstruct the unity of form through the mental process of creative reworking.” Probably it is in all this that the modernity of Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man lies, and it is perhaps for this reason that his depiction is the one best known today: because he was able to stand as a paradigm of a new world, of a different, more rational way of observing reality and explaining the phenomena of nature. It will therefore be no coincidence that, in the passage in which Leonardo states that “l’omo è detto dalli antiqui mondo minore,” the comparison between man and the world concludes as follows: “the body of the earth lacks nerves, which are not there, because nerves are made for the purpose of movement, and the world sendo di perpetua stabilità , non v’accadendo movimento, e non v’accadendo movimento, i nervi non vi sono necessari. But in all other things they are very similar.” What man has more than the world are nerves, the structures that enable voluntary movement. Man is thus animated by a will that makes him “very much the same,” but still different, from the world around him: it is not far-fetched to speculate that it is this important awareness that makes Leonardo so modern.

Reference bibliography- Pietro C. Marani, Maria Teresa Fiorio (eds.), Leonardo da Vinci 1452 - 1519. The drawing of the world, exhibition catalog (Milan, Palazzo Reale, April 16-July 19, 2015), Skira, 2015

- Annalisa Perissa Torrini (ed.), Leonardo: l’Uomo vitruviano fra arte e scienza, exhibition catalog (Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia, October 10, 2009 - January 10, 2010), Marsilio, 2009

- Andrea Bernardoni, Leonardo and the equestrian monument to Francesco Sforza, Giunti, 2007

- Pietro C. Marani, Giovanni Maria Piazza (ed.), Il codice di Leonardo da Vinci nel Castello sforzesco, exhibition catalog (Milan, Castello Sforzesco, March 24 - May 21, 2006), Mondadori Electa, 2006

- Giovanna Nepi Scirè, Pietro C. Marani (ed.), Leonardo & Venezia, exhibition catalog (Venice, Palazzo Grassi, March 23, 1992 - July 5, 1992), Bompiani, 1992

- Massimo Mussini, The “Treatise” of Francesco di Giorgio Martini and Leonardo: the restored Estense Codex, Quaderni di storia dell’arte, University of Parma, 1991

- Fritz Saxl, Lectures, Warburg Institute, 1957 (published posthumously)

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.