Lazzaro Bastiani. An artist on the margins of the greats of the early Venetian Renaissance.

Roberto Longhi-in an essay written between 1925 and 1926, but published posthumously-was able to summarize with a proposition of unusual clarity the critical history of Lazzaro Bastiani, documented as a depentor from 1456 to 1512, when in the list of confreres of the Scuola Grande di San Marco it is noted: “mori ser lazaro bastian pintor a san rafael.” Although he collaborated on several occasions with the most important artistic personalities of the time, such as the Vivarini and Bellini, playing a role that was by no means secondary, Bastiani has been neglected by contemporary critics, complicit in a language judged archaic, ’reactionary.’ To use the words of Licia Collobi Ragghianti, he was certainly not an artist “sustained by a fervid fantastic inspiration; but one that it is perhaps more accurate to call ’abstractionist,’ of absolute coherence to a precise will for order, within the limits, fixed almost a priori, of a given formal language.” If Bernard Berenson in 1916 had downgraded him to the rank of “dependent creature,” “an artist so inconsiderable,” subsequently eminent scholars, first and foremost Roberto Longhi, have attempted to redeem him, venturing to enrich the meager corpus of works signed and dated or whose autography is attested by sources. The new attributions have shed light on the early period, during which Bastiani, while not disdaining to rework motifs and solutions of the city’s best-known artists, made his way in search of a personal language. In the impossibility of dealing with the subject here - for which we refer to the in-depth research of Stefano G. Casu(Lazzaro Bastiani: the production of his youth and early maturity, in “Paragone,” third series, XLVII, 8-9-10, 1996, p. 60-89) and by Gianmarco Russo(Lazzaro Bastiani before 1480, in “Paragone,” third series, LXIX, 142(825), 2018, pp. 3-18) - we will attempt to trace the history, or rather the histories, of some of his most emblematic paintings, made by the painter between the eighth and ninth decade of the fifteenth century, at the height of his career.

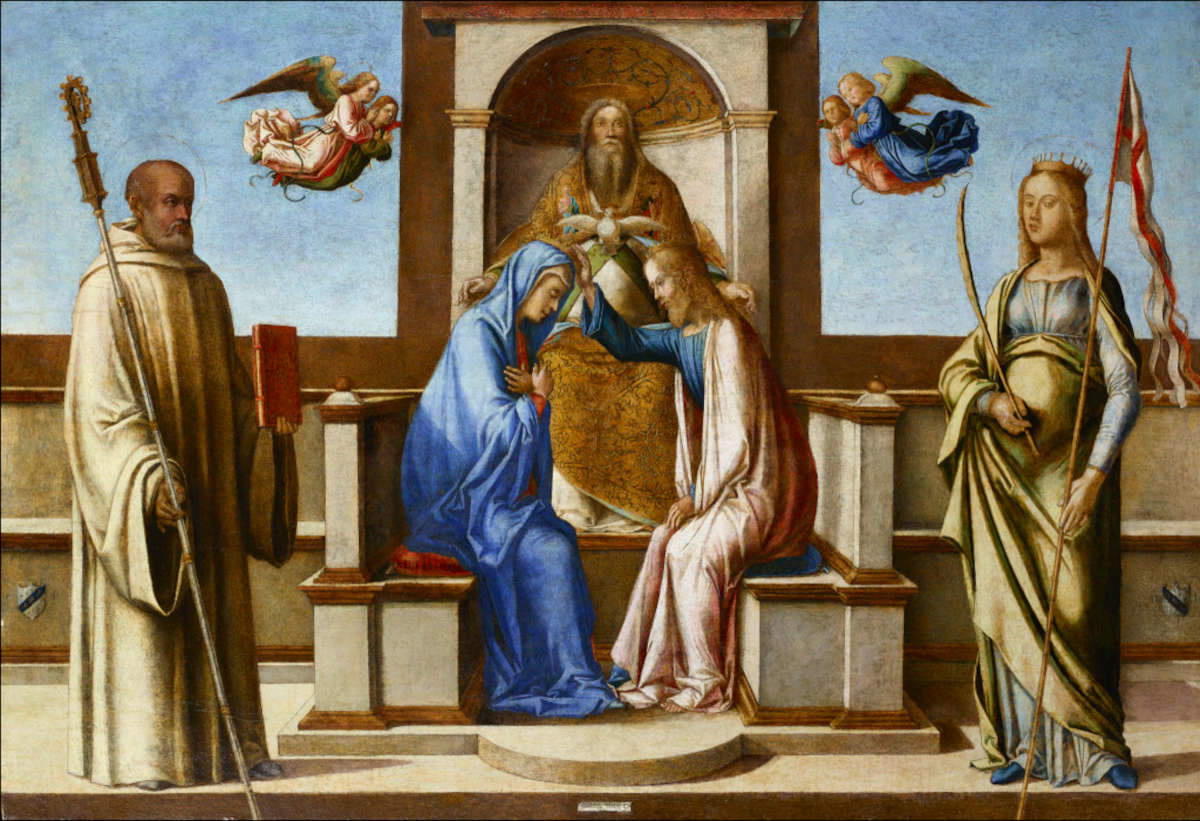

As we shall see, although Bastiani’s ability to make use of perspective as a scientific tool for the distribution of volumes is evident, this does not necessarily imply the search for a naturalistic rendering of the subjects, tending rather to reiterate, with some slight variations, forms and compositional modules, derived in turn from older, fourteenth-century, if not Byzantine formulas. Bastiani’s modus operandi is therefore close to the model that Alexander Nagel and Christopher S. Wood(Rinascimento anacronico, ed. Chiodi, Macerata, Quodlibet, 2024) define as “substitutional,” whereby it is possible to detect the “law of continuity” between his works and previous ones, that is, the anachronic character of his poetics, insofar as it repeats, hesitates and recalls the past, establishing a new present. As Longhi intuited, this language, with all evidence schematic and geometrizing, allows him to make use of “the formal means of the Renaissance for an extrafigurative purpose,” not only religious, but above all promotional and commemorative. Only through careful philological and archival research was it possible to decipher the refined symbolic elaboration of the will of the patrons, restoring the hidden meaning of the subjects depicted.

Among the most eloquent examples in this regard is the St. Augustine Altarpiece, now in a private collection in Montevideo, commissioned from Bastiani in the late 1470s by the regular Augustinian canons of the church of San Salvador in Venice, one of the city’s oldest and most prestigious houses of worship. The work took the form of a polyptych with five compartments, with a Pietà intended for the cymatium and a predella consisting of three panels, one of which depicted, according to Ridolfi, “the Pontiff in the midst à Cardinals” handing over the bishop’s habit to the saint. The Augustinian friars had asked Bastiani to narrate two precise moments in the history of the congregation of San Salvador: the institution sanctioned by Pope Gregory XII in 1407 and the assignment of the Venetian complex to the Augustinian Canons Regular of Bologna by Pope Eugene IV, born Gabriele Condulmer, in 1442. In the painting, the volumes that St. Augustine hands to the confreres, with the scapular and the white rochetto, bear theincipit of the Augustinian rule and refer to these two important events in the institutional history of the congregation, to which is added in the predella the episode of the saint’s episcopal investiture. Bastiani therefore establishes a fruitful dialogue with the canons to restore the memory of the place, preferring a figurative, elegant and allusive narrative.

The same can be said for the panel with the Nativity, made to decorate the altar that stood near the tomb of Eustachio Balbi, podestà of Brescia, in the church of Sant’Elena, located at the eastern end of the city. The latter, in his will drawn up di manu propria in 1478, had ordered that, “in termine de mexi 6” from his death, an altarpiece with “el presepio, tanto bello, et honorevol quanto se po” be made. He appointed his brothers Filippo, Giacomo and Benedetto and his children Andrea, Zaccaria, Cristina and Chiara as commissioners. From the inscription on the plaque we learn that Eustace died in April 1480, so presumably by the end of the year Bastiani fired the painting. The symmetrical arrangement and composure of the figures immediately reveals the “symbolic intention” of the image: the brothers of the deceased, as executors, did not, in fact, miss the opportunity to have their eponymous saints arranged around the sacred scene, in addition, of course, to that of the deceased. We see, from the left, Eustace, wearing armor and a banner bearing his name in capital letters, James, Philip and Benedict, wearing cope and a white robe with wide sleeves, i.e., the habit of the reformed Benedictines of the Olivetan church of St. Helena.

Even more intriguing is the reading of the lunette with the Virgin and Child Enthroned, Saints John the Baptist and Donato, and Donor Giovanni degli Angeli, signed and dated 1484, kept at the Basilica of Saints Mary and Donato in Murano. Thanks to the discovery of the patron’s will, Lucia Sartor(Lazzaro Bastiani and his patrons, in “Arte Veneta,” 50, 1997, pp. 38-53) has not only been able to reconstruct the painting’s original location - on the building’s counterfacade, where a slightly larger niche can still be seen - but has also managed to decipher the subtle puzzle game worked out by Bastiani, according to the parish priest’s instructions. St. John the Baptist accompanies two little angels before the Virgin, while St. Donatus, patron of the Basilica, presents the donor and, as in a rebus, it is possible to deduce his name and the office he had held. The parrot, under the wall on the lower right, a symbol of redemptive eloquence, alludes to the hope of eternal life, as does the curious leaf present behind Saint Donatus, which would recall a beautiful passage from the Book of Sirach (14:18-19): “as green leaves on a leafy tree, some fall and others sprout, so are human generations: one dies and another is born.”

Bastiani employs a stark, linear, iconic language that forgoes an impression of reality to transform sometimes standardized details into powerful signifiers. Abandoning a vision of losers and winners, of great poets and mere debtors, will help us restore the proper dimension to an artist more than well-known in Venice in the second half of the 15th century and wrongly condemned to oblivion by a history too often hampered by trivial matters of taste and style.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.