Lansquenets, the fearsome German mercenaries, in Renaissance art.

“Lanzichenecchi”: whenever this term is encountered in a Renaissance history book, one usually expects nothing good in the following pages. Who were these notorious soldiers, associated in the collective imagination with the violent raids to which they subjected 16th-century Italy during their descents? Why are they also known, in the second order, for their flamboyant and colorful robes? How have they been represented in art history? The first company of Landsknechts (the noun from which the Italian “lanzichenecchi” is derived) was formed in 1487 by Emperor Maximilian I, although the term (derived from Land, “land,” “homeland,” “region,” and Knecht, “servant,” thus literally “servant of the land”) predates and first appears around 1470 to describe the troops of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. The story goes that Maximilian, before becoming emperor, at the time when he ruled jure uxoris the duchy of Burgundy after the death of Charles the Bold, had the opportunity to test the effectiveness of the dreaded Swiss mercenaries during the conflict that pitted Burgundy against the Helvetic Confederation between 1477 and 1477 (with Burgundy’s defeat). Charles I himself lost his life in battle against the Swiss during the siege of Nancy. Maximilian saw fit, in order to protect his lands, to form an army that would count on units like those of the Confederation: thus we come to 1487 and the birth of the first formation of lansquenets.

Most of the lanzichenecks came from southern Germany, and they were usually from humble social backgrounds: they were mostly peasants or poor artisans, but there was also no shortage of bourgeois and decadent aristocrats, attracted by the possibility of obtaining rich rewards during the raids to which they systematically subjected the lands they fought in (but there were also lanzichenecks who fought out of a pure spirit of adventure). They were usually organized into regiments of about four thousand men, recruited by a patron with a letter of assignment in which, as was the case with the Italian companies of fortune in the fifteenth century, the rules of engagement, regimental structure and pay were arranged, and they were commanded by an Obrist, who in turn established the chain of command. Often real armies were formed consisting of several regiments of Lansquenets, which therefore necessitated the appointment of a Generalobrist, a commanding general. Regiments also included chaplains, scribes, doctors, drummers, pipers, paymasters and lodgers, ensigns in charge of carrying flags, and recruiting officers. New recruits were properly trained by the Feldweibel, supervised by an Oberster-Feldweibel, the sergeant major who was in charge of drills. Their way of fighting was similar to that of the Swiss pikemen, who during the 15th century had in fact made a real revolution in the military: they fought with long pikes (although shorter than those of the Swiss mercenaries: those of the lanzichenecchi were about four meters long, one less than those used by the Helvetic Reisläufer), deploying in square formations (like the Swiss mercenaries, who in turn were inspired by the Macedonian phalanx) that numbered about forty men, and most were also equipped with a sword called a Katzbalger (Italian for “lanzichenetta”) that served for close combat. The pikemen received support from halberdiers and soldiers equipped with Zweihänder, or two-handed broadswords: they were the most experienced and preceded the squares of infantrymen, with the double objective of creating a gap between enemy lines and protecting the phalanx. During their first appearances, the lansquenets fought in a straight line, but they soon came to also develop encirclement tactics to attack their opponents on multiple sides.

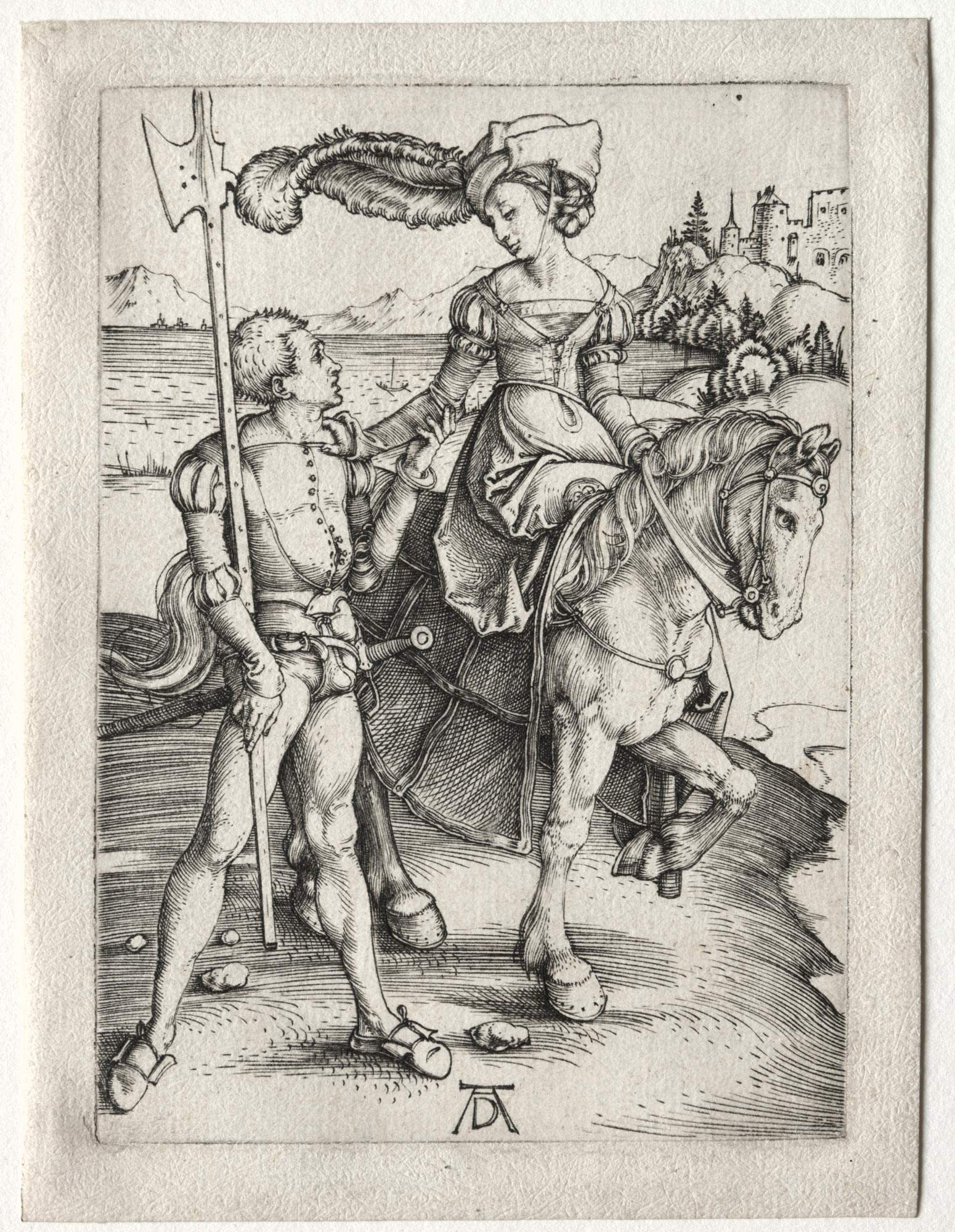

One of the earliest works in which a depiction of a lansquenet can be seen is the Lady on Horseback with a Lansquenet, an engraving by Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528), circa 1497, in which a love scene between a noblewoman and a mercenary is depicted. This is an ironic scene in which the artist lingers on the unusual subversion of roles with the woman who, in this case, by virtue of her higher rank, exerts her dominance over the man: this is evidenced by her higher position, the fact that she is wearing a lansquenet’s hat, and the imposition of her hand on his shoulder. There is also no lack of sarcasm on some elements, such as the hilt of the soldier’s sword, which, placed in that position, unmistakably alludes to his erotic appetites. Much more realistic is the 1524 engraving by Urs Graf (Solothurn, c. 1485-Basel, c. 1529) in which two lansquenets approach a much more affordable and much more typical lover, namely a prostitute. Both works, however, are useful for observing the typical attire of the lansquenets, who, it is worth remembering, did not wear uniforms (at least in most cases) and had no distinguishing marks for hierarchies. Each soldier was free to dress as he wished, although certain garments were very common: a braguette or “braghetta” (in German Latz or Hosenlatz), or a kind of genital pouch, made of leather or colored cloth; a linen shirt that was covered with a garish farsetto with sleeves cut into puffs (to make the larger the wearer’s build), and then again a very tight-fitting tights that could be covered (as seen in Graf’s engraving, while Dürer’s lansquenet wears nothing over this garment) by a pair of loose, two-colored pants, called Pluderhosen. On their feet, as can be seen from the engravings, the lansquenets wore leather gaiters, which gradually came to replace the pointed footwear typical of late Gothic fashion, and which had a wide sole and were cut at the front, reminiscent of the shape of an animal paw (hence the name Bärenklauen, or “bear claws”). However, there was no shortage of lansquins wearing tall boots. Headgear could come in a wide variety of shapes, but it was almost always gaudy, extravagant, and decorated with long feathers.

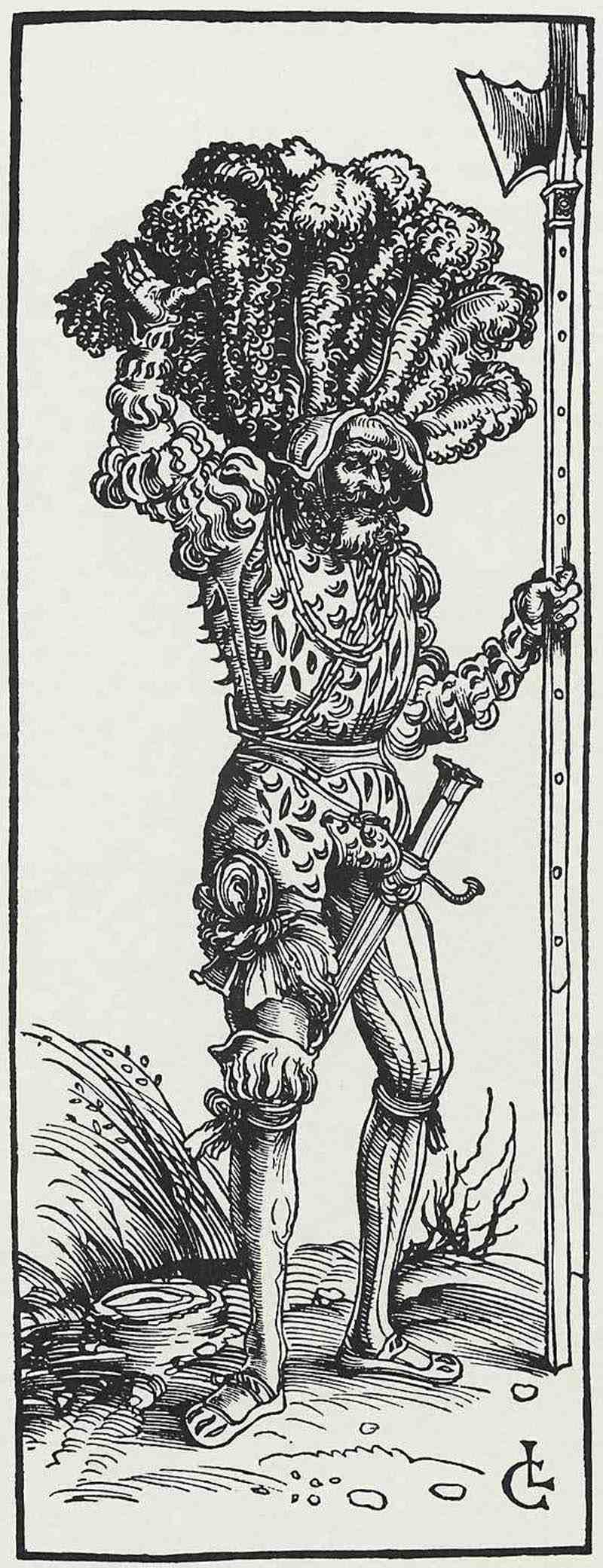

At times, the garments of the Lanzichenecks were also very fanciful, as seen in a drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger (Augsburg, 1497/1498 - London, 1543) depicting the Lanzichenecco Christoph von Eberstein, who is shown wearing a richly decorated jacket while posing with his halberd on his shoulders and his Katzbalger in his left hand. The same can be said of Lucas Cranach the Elder ’s (Kronach, 1472 - Weimar, 1553) Lanzichenecco, who is striking because of the gaudy feathers he wears on his headgear, forming a sort of crown: this is, moreover, one of the first engravings to depict a lanzichenecco alone (a genre of images that became widespread in the early sixteenth century).

What were the origins of such a seemingly strange mode of dress for fierce soldiers such as the lanzichenecchi? Meanwhile, clothing was a distinguishing mark for them: the more conspicuous it was, the more the soldier stood out from others (in addition to this, some have thought that the lansquenets, usually from humble social backgrounds, wanted to imitate the flamboyant clothing typical of the nobility). Moreover, the lansquenets were exempt from the suntuary laws that, in late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century Germany, obliged citizens to wear clothing that avoided ostentation: mercenaries were exempt from the obligation because their lives were usually short and difficult, and they wanted to avoid demotivating them. There may then be a motivation of historical origin: during the Burgundian wars, the Swiss used to fix their battle-torn garments with rich silks taken from the Burgundians (a land known for its textiles), and consequently the Lansquenets, with their colorful garments, may have imitated this practice. However, the more plausible hypothesis, explained historian Peter H. Wilson, is that of fashion as a distinctive element: “it is more likely that the style [of the lansquenets] emerged as an exaggerated form of more general trends, stimulated by the competitive and flamboyant culture of the soldiers.”

It is difficult to find lansquenets in paintings (owing to the fact that drawing and engraving were, at the time, the favored means of illustrating strictly topical subjects, while paintings were reserved for genres deemed more noble), but not impossible: one example is the painting of the Battle of Pavia executed by Ruprecht Heller, a German painter active around 1529, where we can see lansquenets intent on battle in their colorful robes. And speaking of the Battle of Pavia, lansquenets can also be seen in the famous series of Flemish tapestries dedicated to this important clash that took place as part of the Italian Wars: this is the battle fought at Pavia on February 24, 1525 between the French army of Francis I and the imperial army of Charles V consisting of 12.000 Lansquenets and 5,000 soldiers of the Spanish tercios, formations that were greatly feared because they were capable of modern combat using both bladed weapons and firearms, and because they were composed of professional, disciplined, and motivated soldiers (they were thought to be all but invincible). The battle was won by the Imperials, who inflicted devastating losses on the French (who, on the contrary, lost almost half of their forces) with few casualties. The tapestries, now in the National Museum of Capodimonte, were commissioned by the States General of the Netherlands as a gift to be sent to Charles V (or his sister Mary of Hungary). The tapestries, the design of which was the brainchild of Flemish painter Bernard van Orley (Brussels, c. 1491 - 1542), while the weaving was the responsibility of Jan and William Dermoyen, provide what is perhaps the best color depiction of the lansquenets in the early part of the 16th century, with a great variety of poses and clothing, with weapons and clothes depicted in a manner decidedly faithful to reality, and with the soldiers in the foreground being individually connoted. It is also unique in that the tapestries of the Battle of Pavia represented the first cycle of tapestries devoted to a contemporary event.

Lucas

Lucas

A particularly curious episode in the history of Renaissance Italy is that of the "lanzi della Loggia," or guard of German soldiers who were formed by Cosimo I de’ Medici in Florence in 1541: even today the loggia in Piazza della Signoria where these soldiers were quartered bears the name "Loggia dei Lanzi.“ In June 1541, the duke of Tuscany dismissed the garrison of Italian soldiers commanded by Pirro Colonna (according to the chronicles, the pretext was a game of trumps lost by the irascible commander, who out of anger beat up a court dwarf) and formed his new guard, which must also be seen as a move as part of Florence’s rapprochement with the empire. Although for the Florentines the soldiers protecting Cosimo I and consort were nothing more than ”lanzi," the Medici maniple was not composed only of Landsknechts, although there were soldiers among their ranks who had served as Landsknechts for Charles V: they were mostly Trabanten (“trabanti” in Italian), or guard soldiers. The dress, however, was entirely similar to that of the Landsknechts.

In the first fifty years of its history, the Medici “lanzi” were commanded by an imperial captain(Hauptmann), of direct ducal appointment (or grand ducal from the date Tuscany became a grand duchy). It was from the grand duchy of Ferdinand I that the captain also began to be recruited from among Italian noble families (the first, in 1591, was the Emilian Ferrante Rossi di San Secondo), although the rest of the troop, for the two centuries that the lanzi garrison remained in service, was composed of German soldiers. Compared to the negative history that distinguishes the Lansquenets, the Lanzi of Florence had a peaceful history instead: “after the end of the Wars of Italy,” historian Maurizio Arfaioli explained in the catalog of the exhibition that the Uffizi dedicated in 2009 to the lanzi, “Florence always managed to avoid direct military threat” and “on the home front, the solidity of the political project and the professionalism of the German Guard meant that, in order to protect the safety and quiet of the grand ducal family and court from both external and internal threats and turbulence, in practice the lanzi could limit themselves to using the rods or the flat of the blades of their halberds.” This was a constant presence in Medici Florence, not least because the German Guard, being part of the court ceremonial, attended all public events, so much so that the “lanzo” became a sort of figure in Florentine folklore: “a faithful but stolid soldier,” Arfaioli explains, “and, above all, endowed with a prodigious thirst for wine.” The lanzi of Florence were then forgotten after the Risorgimento, a time when they were seen as the scoundrels of a tyrannical power, and their memory survives, however, in the lodge that still bears their name. And, of course, in the works of art: They can be seen, for example, in a series of lunettes painted roughly between 1620 and 1640 by an anonymous Florentine who painted some views of the city in front of which some official ceremonies are held, with the lanzi escorting members of the court (the works are now in the deposits of the Pitti Palace), or in some of the biccherne preserved in the State Archives of Siena (in one of these, depicting the solemn entry of Cosimo I into Siena, which took place on October 28, 1560, we witness what is perhaps the first known depiction of the German Guard, since the panel was executed in that same year).

The lansquenets were protagonists in some of the most important battles of the Renaissance. In Italy they were employed, for example, in that of Bicocca in 1522 and in the aforementioned Battle of Pavia in 1525, all occasions in which their contribution was decisive. In Italy they became infamous in 1527, when they again descended on the country and put Rome to the sword, committing violence, killing, raping, and pillaging (the terrible episode went down in history as the Sack of Rome: 14.000 Lansquenets, commanded by Georg von Frundsberg, entered the city on May 6 and, disappointed with a military campaign that up to that point had not given them the results they had hoped for, vented their brutality against the defenseless population, against palaces, against churches). Thus, in his History of Italy, Francesco Guicciardini described the beginning of the Sack of Rome: “Having entered inside, each began to speak tumultuously to the prey, having no respect not only to the name of friends nor to the authority and worthiness of prelates, but eziandio to temples to monasteries to the relics honored by the concourse of the whole world, and to wise things. Hence it would be impossible not only to narrate but almost to imagine the calamities of that city, destined by the order of heaven to supreme greatness but eziandio to thick directions; for it was the year that it was sacked by the Goths. Impossible to narrate the magnitude of the prey, there being accumulated there so much wealth and so many precious and rare things, of courtiers and merchants; but made it still greater by the quality and great number of the prisoners who had to be bought back with very large bounties: still accumulating misery and infamy, that many prelates taken by soldiers, chiefly by German foot soldiers, who out of hatred of the name of the Roman Church were cruel and insolent, were in on vile beasts, with the garments and insignia of their dignities, driven back with great vilification throughout Rome.”

It was mainly as a result of this episode that the term “lanzichenecco” took on a negative connotation: the German soldiers were otherwise known for their discipline, and the raids of the 1620s were mainly due to a series of mutinies (due to non-payment) that struck the imperial army between 1526 and 1527. Until then, the lansquenets had not proved more bloodthirsty or more violent than other mercenary soldiers. And precisely since the disastrous episode of the sack of Rome, the term “lanzichenecco” has taken on a derogatory connotation.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.