Laetitia Ky. The Gaze of Medusa

Laetitia Ky (Abidjan, 1999), a very young artist from the Ivory Coast who has become famous for the “sculptures” she makes with her own hair, is one of the most talked-about African artists of the moment. She has exhibited her work at the Venice Biennale 2022, at the Ivory Coast Pavilion, at the Empowermentexhibition at the Kunstmuseum in Wolfsburg, which brought together 100 women artists to reconstruct the history of feminism in art (one of her works was chosen for the cover of the catalog and for the exhibition poster), and will soon be exhibiting at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Caen, in an exhibition dedicated to the Medusa myth alongside very famous international artists, and in a series of solo shows. Until January 15, 2023, Lis10 Gallery in Arezzo is dedicating to her the exhibition Empow’Hair, curated by Alessandro Romanini. The following text is taken from the critical text that Romanini, curator of the Ivory Coast Pavilion at the 2022 Biennale, wrote for a solo exhibition of Laetitia Ky’s work that will open March 4 in Naples.

From the very beginning of her aesthetic-militant operation designed and conducted from her home-atelier on the outskirts of Abidjan, the work of the very young Laetitia Ky has aimed to produce works that could simultaneously incite viewers to reflection and promote the female condition. That condition that in the art world has struggled to assert itself over the centuries and has long remained in a condition that passes “from chronicle to eternity without enjoying a moment of history,” as Lea Vergine stated in her famous essay-catalogue The Other Half of the Avant-Garde. 1910-1940. A complex of creative minds that suffered discrimination, which soon became automatism destitute of all acrimony, that created a ghetto that did not dialogue with the center of the artistic mainstream and generated a host of fierce Eurydices without Orpheus, princesses without need of blue princes.

Cheik Amidou Kane’s essay The Ambiguous Adventure, among the landmarks of Laetitia Ky’s work, was published in 1961, on the wave of enthusiasm for the many independence gains of African countries that occurred in 1960. This happy conjuncture confronted Africans and particularly artists and intellectuals with the need to structure a new cultural, identity and expressive form with which to present themselves in their new autonomous and independent guise. For women artists, this attempt at redefinition has continued for a long time and is still continuing.

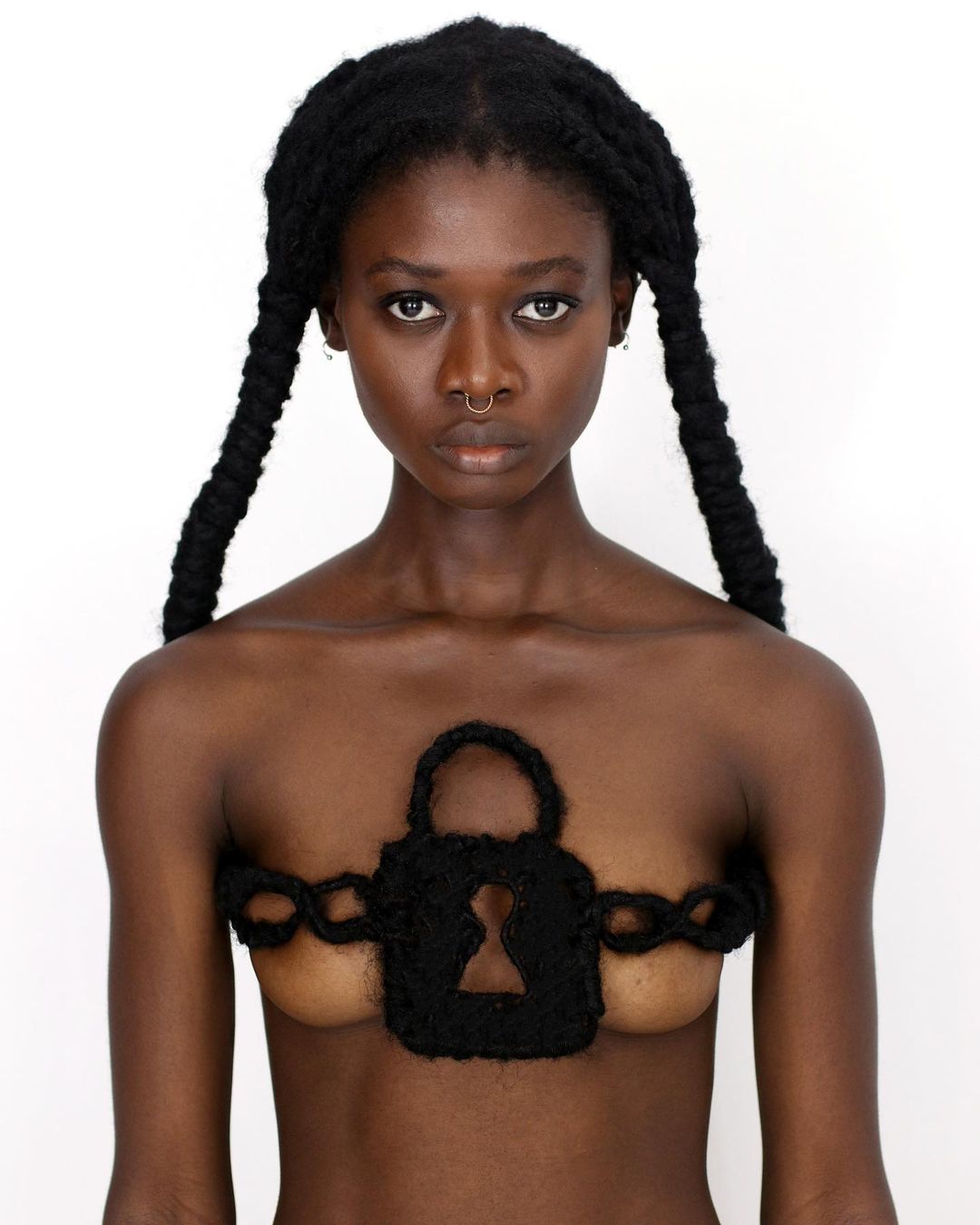

First and foremost, the Ivorian artist’s choice to put herself on the line in the first person, portraying herself in photos; the choice of the expressive medium, of the “hair sculpture,” arose from the conjuncture of a series of events; the state of dissatisfaction, little more than a teenager, with the conditions of women’s rights in her country and the need to express herself in a way that would claim her own identity and pride. "At first, I discovered on social networks archival images, photographs dating back to precolonial times, of women with elaborate hairstyles, real sculptures, and this immediately sparked an idea in me, associated with the widespread fashion for African women to straighten their hair in order to resemble Westerners. That is, to reject curly, wavy, frisé hair, a real symbol of identity."

Laetitia

Laetitia Laetitia

Laetitia

So in the first instance there is a desire for vindication, where hair represents not only a genetic code, but a symbol of pride and cultural identity. "From that moment I decided to start from hair to build my own expressive language. Photography and social networks seemed to me the most suitable tools to create at the same time a form of subjective expression and a method of dissemination, which allowed to circumvent the economic and resistance difficulties of the art system, provided by renting a studio, materials and presenting one’s work to galleries and dealers. I, with my body and mind am always available to create ideas and works, without the need for outside help." Particularly interesting in the context of this identity ambiguity, to record the coincidence between the claim of an identity culture by African artists and that of women artists in general, which occurred beginning in the early 1970s. At that time, both were taking their first uncertain steps, focused totally on claiming the right to existence.

After a blackout in the 1980s (e.g., Italian women artists disappeared from the international scene), some African women artists at the end of the decade began to appear on the scene like their male counterparts, aided and abetted by the Magicien de la Terre exhibition at the Centre George Pompidou in Paris. The late 20th century edition of the Venice Biennale awards a virtual pavilion composed of works by women artists only: Medial Practices in Women’s Art 1977-2000. Laetitia Ky consciously brings her own body and identity into play, synergistically combining a performative dimension with a plastic one and photographic mediation. In this context, the operation performed by the Ivorian artist calls to mind the words of Rosalind Krauss in Bachelors: “The true conceptual form of the problem begins elsewhere...with the meaning of a cage for the body it holds. Isn’t that space square? What does it feel like to be put on display? What does the word ’always’ really mean? What would it be like to be eternally, at the center of someone else’s gaze?”

The artist is both photographer and model of herself, subject and object at the same time, using her body to proceed on the path of self-knowledge-and not of a generic representational model-and of the African female world, of which she feels an integral part. It is an attitude that also involves an ethical dimension her own, which she unravels through a conflict against the media system and the invasive barrage of images that are daily disseminated in the infosphere.

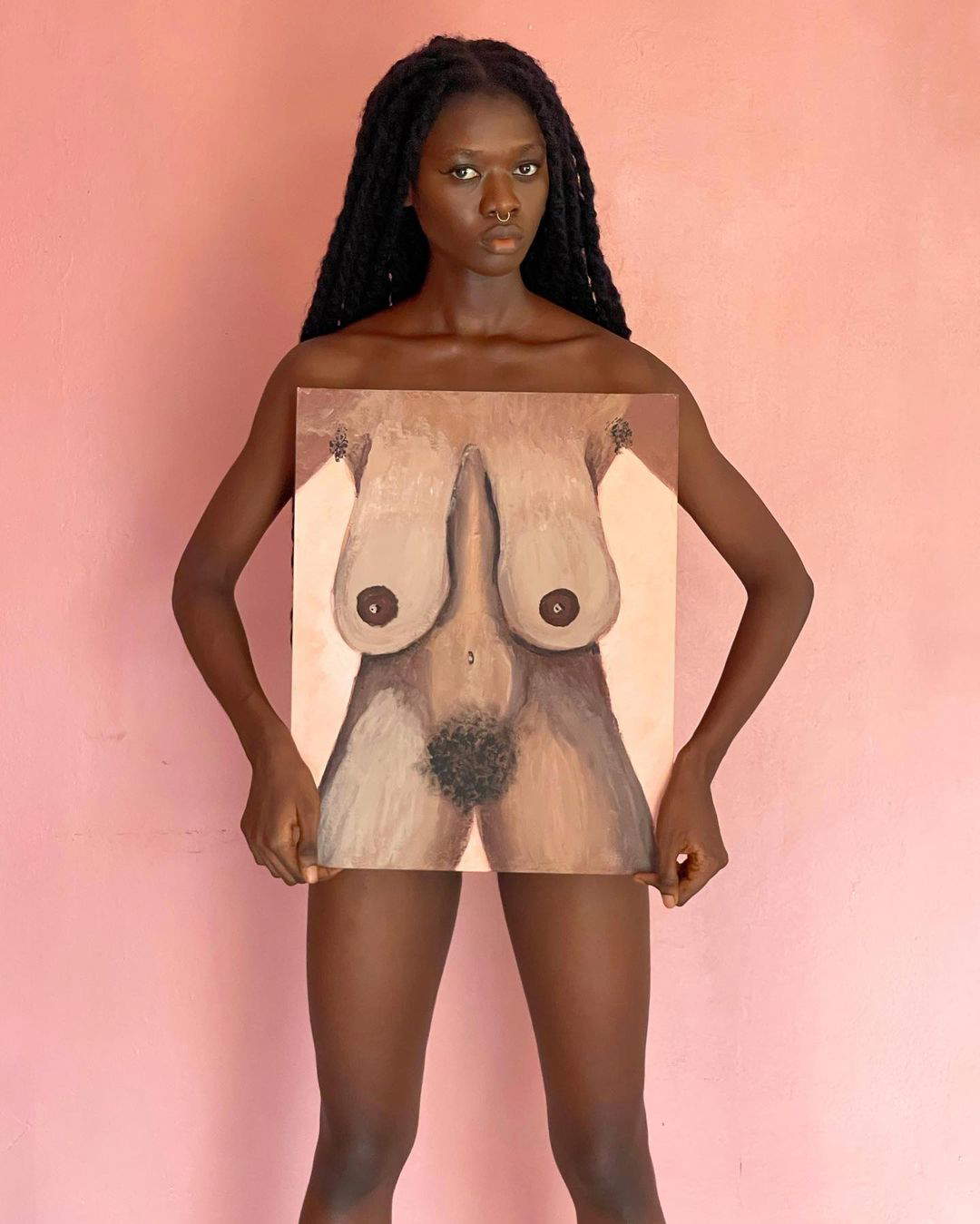

Unlike most of the images that are consumed on a daily basis, in which the body is treated as a bargaining chip between author and viewer, Laetitia Ky uses her body to instigate reflection and open a dialogue with herself; she inserts her body into neutral scenarios or spaces that enrich the diegesis of the photograph and the meaning it is intended to convey. All of this is consciously designed to transform her body into a communicative device, a meeting place between herself and the outside world, a communicative model on which information about her identity experience is reflected and transmitted in relation to the context in which it develops. With these dynamics, she transforms her body and hairstyles into models for investigating her vision of the existing and not the image that others may have of her body. The artist projects images and symbols onto the female body, ambitions, claims, fears, and even anger. She adds layers of reflection and mimicry in the structure of the photo depicting the “plastic hair performance,” to break free from the mere objective mechanical reproduction of the photograph.

Laetitia

Laetitia Laetitia

Laetitia

The poses and plastic “constructions” of the hairstyles, are also a symbolic representation of reality and of the specific female universe: it is as if the artist constantly investigates at the same time, the formation of her young developing personality, staging desires, claims and vulnerability and the condition of women in the specific cultural context. An operation that simultaneously includes a metalinguistic reflection on her way of making art and on gender

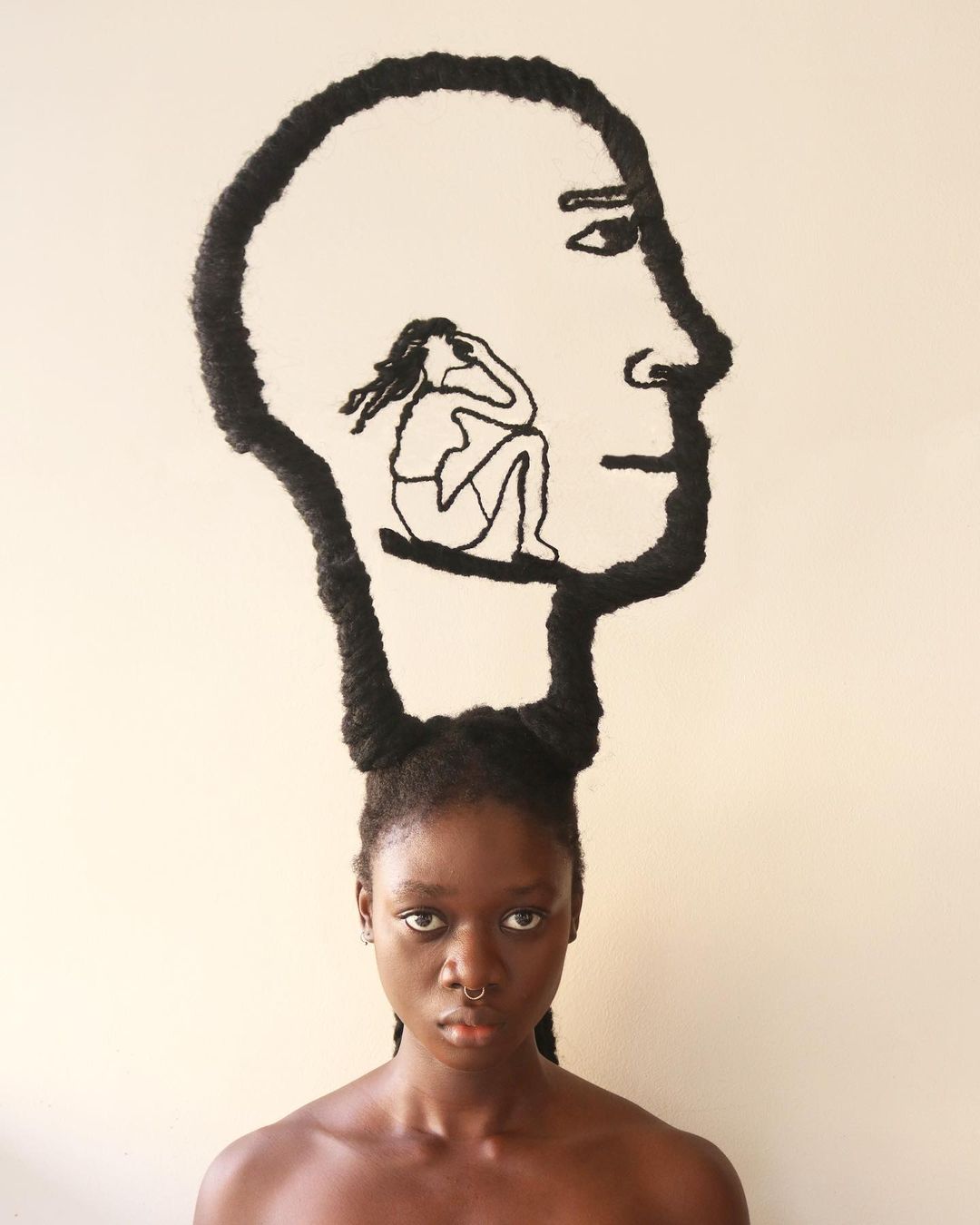

Medusa’s Gaze. Recognized as an ideal model for this new creative path by the artist; the hair - snakes, as an element of connotation and threat, the gaze, with all its perceptual and creative implications, as a weapon, which petrifies those who cross it, transforming them into a stone sculpture. A metaphor for a creative process enacted by the Ivorian artist that always involves some sort of threatening, militant element, complicit in the hair sculpture, the taking on of a female identity that is already in itself claiming. A gaze that is embodied in the photograph, which crystallizes an ephemeral, performative and therefore “time-based” interpretation, making it ascend from an autobiographical dimension to one linked to the collective imagination and memory.

A menacing but also threatened gaze the one fielded by Laetitia Ky’s works, as if it were waiting for Perseus’ deadly slash and thus had to act in a continuous state of urgency and emergency; fiction and reality in this context touch each other, crossing also history, chronicle and mythology, pivotal elements of all identities. But also a protective, guardian gaze that surrounds the female “characters” played by the young artist, as indicated by the root of the term Medusa in ancient Greek. Medusa one of the three gorgons, the only one who shares the mortal nature of humans and stands in an empathic dimension with them. Endowed with a deadly power, able to petrify anyone who crosses her gaze but also the great handicap of not being able to look into the eyes (into the soul... ) of any living being; a metaphor for the artist who lives in an ambiguous dimension, within a society, a historical conjuncture, inserted in turn into a historical process, which leads him to assume responsibilities. At the same time inside and outside history and the chronicle.

Perseus with the winged sandals provided by the nymphs and the helmet of invisibility from Hades and the adamantine sickle granted by Hermes, observing Medusa’s reflection in his shield (and never a direct glance), to avoid being petrified, manages to decapitate the gorgon. Split image, reflection, simulacrum and metaphorically symbol of an other gaze, a mediated identity, simulacrum.

Laetitia

Laetitia Laetitia

Laetitia Laetitia

Laetitia Laetitia

Laetitia Laetitia

LaetitiaA death that is also symbolically a harbinger of creation (creativity), causing the winged horse Pegasus and the giant Chrysaor, the children he was expecting from Poseidon, to spring from the bleeding wound. Other sources state that coral also sprang from the wound Perseus inflicted. Perseus carried Medusa’s severed head with him, turning her gaze (of the deceased..who had not lost her power) into a weapon against his enemies. Perseus significantly, after killing Medusa, traveled to Africa with the powerful head of his victim; on the ancient continent he defeated Atlas, giving life by carving the Atlas mountain range in stone form. Also in Africa he petrified the sea monster that threatened Andromeda, princess of Ethiopia, marrying the maiden.

The inseparable union of eros and thanatos guaranteed by photography. Laetitia Ky is aware that “every photograph is a memento mori” as Susan Sontag pointed out, “to take a photograph is to participate in the mortality, vulnerability and mutability of another person or thing. And it is precisely by isolating a particular moment and freezing it that all photographs attest to the inexorable dissolving action of time,” the American philosopher and historian explains. This is perhaps the ultimate core that binds the series of Laetitia Ky’s photographs, an irrepressible need to claim identity, in which is inscribed the expressive urgency, dictated by a condition to be altered and above all by the threat of the incessant action of the tyrant Cronus.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.