Japan according to Vincent Van Gogh

In the last months of 2012, an exhibition with the eloquent title Van Gogh, rêves de Japon, or: “Van Gogh, dreams of Japan,” opened at the Pinacothèque de Paris. The exhibition aimed to document the influence thatJapanese art had exerted on the production of Vincent van Gogh (Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890): a profound influence, which the artist received with an enthusiasm and passion that also shines through in several letters van Gogh exchanged with his loved ones and friends. The first mention of this new interest was in a letter dated November 28, 1885. Van Gogh had recently left Neunen, a country town in North Brabant, and moved to Antwerp, a city with one of the busiest ports in Europe, into which cargoes of goods arrived daily from all corners of the globe. We have to imagine a van Gogh strolling through the streets of the Belgian city, coming across one of the many Japanese prints that had also taken to arriving continuously at the port of Antwerp and then being sold in the city’s stores. This was in the wake of a fashion that had started in France some twenty years earlier, but also thanks to the impetus of theUniversal Exhibition of 1885, which had been held precisely in Antwerp, and which had contributed to making Japanese art known in Belgium as well. In the above letter, Vincent wrote to his beloved brother Theo that he had hung a small series of Japanese prints on the walls of his atélier: “my studio is now more bearable.” Indeed, Van Gogh found those “little female figures in the gardens or on the shoreline, the horsemen, the flowers, the thorny, twisted branches” “very amusing.”

Before long, Van Gogh was able to build up his own personal collection of Japanese prints (the japonaiserie, as he called them), favored by the fact that these works were on the market at decidedly modest prices: even an artist who, like himself, was certainly not rolling in gold, could afford them. Vincent’s passion for Japanese prints grew when he moved, in 1886, to Paris, where they could be found practically everywhere and where, as mentioned, the fashion for these works had long since found fertile ground for its spread. In the French capital, Vincent became a frequent visitor to the gallery of Siegfried Bing (1838 - 1905), a Franco-German dealer who had set up shop on the rue de Provence. Bing’s gallery had been instrumental in introducingFar Eastern art to France. The same merchant had made a trip to Japan in 1880, and in 1888 he would found a newspaper, Le Japon artistique, to further spread the news of Japanese art. The artist also came up with the idea of organizing a small exhibition of Japanese prints on the premises of the Café du Tambourin: it was, however, a complete disaster from a commercial standpoint, as Vincent himself acknowledged in a letter sent to Theo, on July 15, 1888, from Arles. However, in the letter, the artist asked his brother not to close relations with Bing: while it was true that the artist had spent a great deal to set up his collection, often even having to pay the dealer late, the benefits derived were of considerable importance because, Vincent wrote, the opportunity to frequent the gallery and collect prints had introduced him to Japanese art. Among the various prints Van Gogh had purchased was the famous Shin-ÅŒhashi Bridge in the Rain, by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797 - 1858).

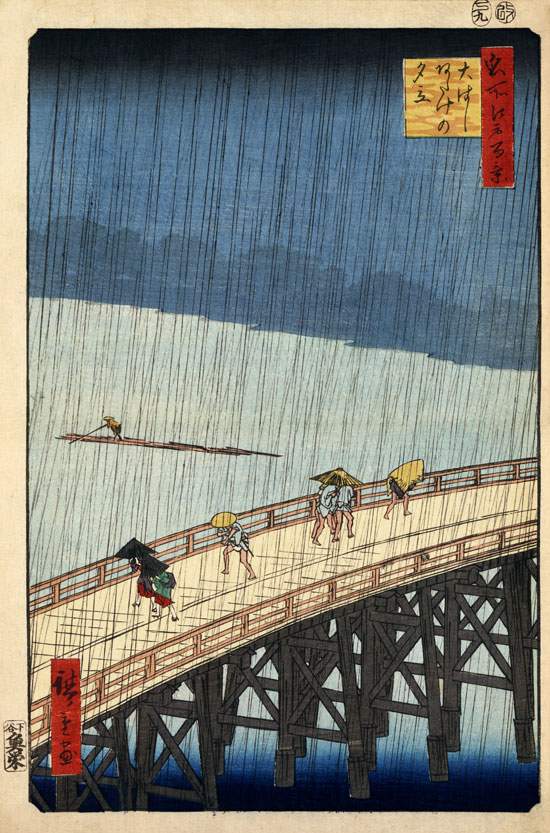

|

| Utagawa Hiroshige, Shin-ÅŒhashi Bridge in the Rain (1857; ink and color on paper, 34 x 24 cm; various locations) |

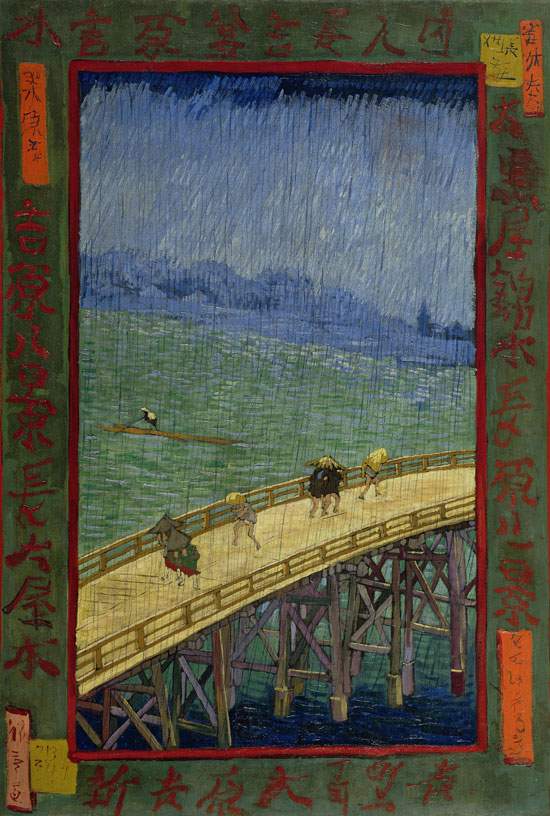

The work belongs to the genre known as ukiyo-e (literally, “pictures of the floating world”). These were prints on paper made with the use of wooden matrices, depicting mainly landscapes or scenes of everyday life, and employing a style based on the use of often bold perspectives and unusual viewpoints, the concentration of the main action at a precise point in the painting (typically in the foreground), the absence of symmetry, and bird’s eye views. Colors were spread in uniform backgrounds over areas rigidly delimited by dark outlines, almost entirely devoid of shading and chiaroscuro effects. These are all features we find in Hiroshige’s Bridge. The main details of the work are all concentrated downward: the wooden bridge, the figures occupying the center of the composition who seem almost to be running, sheltering themselves from the water (note how they cast no shadows on the ground: this is typical of ukiyo-e), the boat coming over from the left. The different shades of blue that the artist uses to describe river and sky are also rigidly distinct (only near the edges do we see shading), while the rain is suggested simply by black lines that run through the entire woodcut vertically (the relationship between vertical and horizontal lines is crucial in ukiyo-e as it dictates the structure on which scenes are organized). In 1887, Van Gogh made, from Hiroshige’s Bridge, a painting now housed in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. The Dutch artist decided to preserve Hiroshighe’s sense of dynamism (achieved in this work mainly by means of the side viewpoint), while reinterpreting it according to his own sensibility: we observe on the surface of the river rapid brush strokes, typical of Van Gogh’s style, which allow the juxtaposition of various shades of blue and green in order to suggest the movement of the water. The brushstrokes become broader near the bridge piers against which the waves break, and different tones of brown are used for the same piers. In addition, the painter enriched the frame with faux scriptures, which have no literal meaning because Van Gogh did not know Japanese, but help to give the composition an exotic, Oriental tone.

|

| Vincent Van Gogh, Bridge in the Rain (1887; oil on canvas, 73.3 x 53.8 cm; Amsterdam, Van Goh Museum) |

|

| Comparison of Hiroshige and Van Gogh |

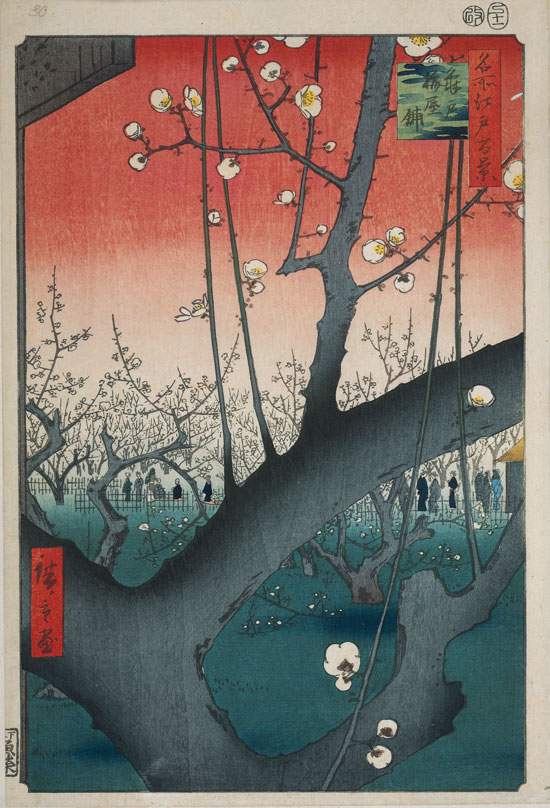

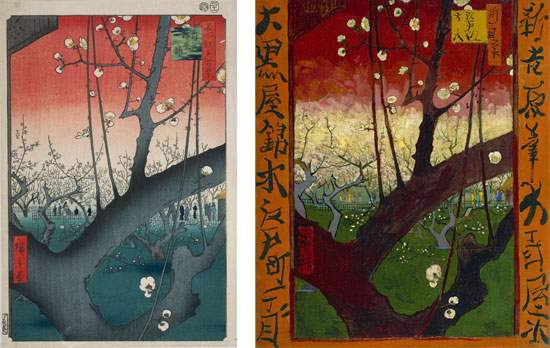

The fact that Van Gogh did not aim to create faithful copies of Japanese originals also shines through in Plum Blossom, another 1887 japonaiserie made from another Hiroshige print, Kameido’s Garden, from 1857. The delicate shades of pink that Hiroshige had used for the sky are transformed into a dense, strong red by Van Gogh, who used decidedly more vivid colors than those in the Japanese prints, although he was inclined to retain the even, black outlined way of spreading the backgrounds: and it is worth remembering how the use of black and outline, practices that the Impressionists had effectively abolished, were reintroduced by Van Gogh, who made use of black and outline with the aim of creating contrasting effects between the elements of his compositions.

|

| Utagawa Hiroshige, The Garden of Kameido (1857; ink and color on paper, 36 x 24 cm; various locations) |

|

| Vincent Van Gogh, Plum Tree in Bloom (1887; oil on canvas, 55.6 x 46.8 cm; Amsterdam, Van Goh Museum) |

|

| Comparison of Hiroshige and Van Gogh |

Why was Van Gogh so strongly attracted to Japanese art? There are mainly three reasons that make Hiroshige’s prints and others so interesting in Van Gogh’s eyes: perspective, simplicity, and colors. Dutch art favored the central point of view: for Vincent, those bold views and unusual vantage points represented impressive novelties. Van Gogh’s purchase of Japanese prints and, in some cases, reinterpretation (as with the Bridge and Plum Tree above) were activities aimed at studying new viewpoints to apply to his own landscapes. On simplicity, this is how Vincent expressed himself in a letter to Theo, September 24, 1888: “What I envy the Japanese is the extreme clarity that every element has in their works [...]. Their works are as simple as a breath, the Japanese manage to create figures with few but sure strokes as easily as we button up our waistcoats. Ah, I must be able to create figures with few strokes, too.” And even the way of spreading colors through uniform masses enclosed by dark outlines, so new and different from the backgrounds the artist was used to seeing in the works of his countrymen, would soon begin to enter his artwork as well.

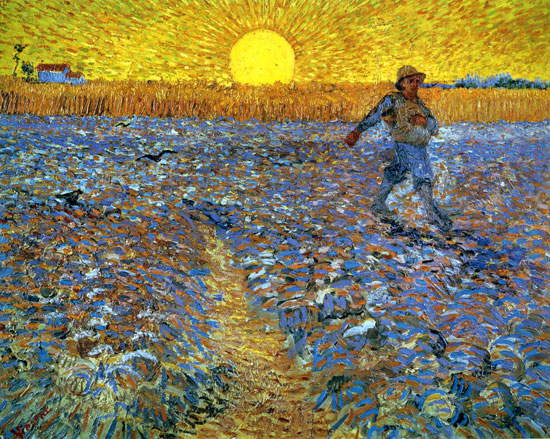

Japanese art, however, was not enough to give Van Gogh’s art the luminosity and bright colors he so longed for: thus, in 1888 Vincent decided to leave Paris and move to the south of France, settling in Arles, a beautiful town of ancient origins near the Camargue marshes. The destination was not chosen at random: Van Gogh found that there was a solid link between the French south(le Midi, as French-speaking people call it) and the Land of the Rising Sun. The reasons for the move were entrusted, as always, to his correspondence: among the most significant is one written on March 18, 1888, from Arles to the painter Émile Bernard. In the letter, Van Gogh said that Arles was the ideal place for “artists who love sunshine and color,” and that the town’s atmospheres reminded him precisely of those in Japan because of their clarity and the splendid colors of the landscapes: “the streams create beautiful blue and emerald patches in the landscape, as seen in Japanese prints, the pale orange sunsets make the fields look blue, and the sun is a splendid yellow.” And all this, Vincent observed, was only in the month of March: summer would hold even more surprises. There is one painting that seems to give shape to all these thoughts: the Sower, a work from 1888 now in the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, the Netherlands.

|

| Vincent Van Gogh, The S ower (1888; oil on canvas, 64.2 x 80.3 cm; Otterlo, Kröller-Müller Museum) |

|

| Vincent Van Gogh, Sketch for The Sower contained in letter to 627 to John Peter Russell sent from Arles on Sunday, June 17, 1888. |

The painting, which found an illustrious precedent in the art of Jean-François Millet, presents us with the figure of a farmer intent on sowing wheat in the middle of June, as the sun disappears below thehorizon, flooding the sky with yellow light and, as the artist wrote to Bernard three months earlier, making the field appear blue. The skillful use of complementary colors (i.e., the primary color combined with the secondary color resulting from the mixing of the other two primaries), in this case blue and orange, causes the latter to enhance each other, giving the painting greater luminosity. We are familiar with the genesis of the painting and are able to date it with certainty, because it is first mentioned in a letter dated June 17, 1888, written in English to the Australian Impressionist John Peter Russell: also interspersed in the text is a sketch of the “difficult subject to deal with” that Vincent would also tell Bernard and his brother Theo about a few days later, in great detail, without neglecting references to Millet. Van Gogh’s painting takes us back to a dimension of harmony with the elements, in which the work of the sower is yes hard and tiring, but respects the rhythms of nature, and in which human presence seems to be lost in the fiery light of an early summer sunset in southern France. It is a landscape in which the only sound to be heard is that of foliage moved by the mistral: the same sound Vincent could hear while painting the picture, studied directly on the spot, and right under the mistral wind, as he wrote to Bernard on June 19. Van Gogh had dreamed of Japan, and perhaps he was able to find it in Camargue. So much so that he wrote to his brother, “I feel as if I were in Japan,” or “here I don’t need Japanese prints, because every day I tell myself that here I am in Japan.” Attempts at self-doubt by a troubled artist, or genuine but ephemeral serenity destined to vanish within a few months?

Reference bibliography

- Nathalia Brodskaya, Le Post-Impressionnisme, Parkstone International, 2014

- Marc Restellini, Sjraar van Heugten, Wouter van der Veen (eds.), Van Gogh, rêves de Japon, exhibition catalog (Paris, Pinacothèque de Paris, October 3, 2012 - March 17, 2013), Pinacothèque de Paris, 2013

- Rachel Saunders, Le Japon Artistique: Japanese Floral Pattern Design in the Art Nouveau Era, Chronicle Books, 2011

- Gioia Mori, Impressionism, Van Gogh and Japan, Giunti, 1999

- Alfred Nemeczek, Van Gogh in Arles, Prestel Pub, 1995

- Jean-François Barrielle, La vie et l’uvre de Vincent van Gogh, Vilo Editions, 1984

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.