Jan Fabre, the warrior of beauty who dialogues with the great masters of the past

The traveler who had happened to be in Florence in 2016, during the warm weather, and to be exact between April 15 and October 2, would have come across an unusual presence in Piazza della Signoria: the space in front of the monument of Cosimo I on horseback, one of Giambologna’s masterpieces, was occupied by an enormous polished bronze tortoise ridden by a man holding its reins. It was one of the most famous sculptures produced by the inspiration of Jan Fabre (Antwerp, 1958), and the name the artist wanted to give it was Searching for Utopia (“In Search of Utopia”). And to think that the work was created for a momentary context, that of the first edition of the Beaufort Triennial, in Belgium, the artist’s native country: its success was then such that it led Fabre’s large turtle to travel halfway around the world and to be replicated in other versions. TheUtopia to which the title refers is that of

Searching for utopia, however, is not just a work that takes on the burden of conveying Jan Fabre’s ideals to the relative. Underlying this masterpiece there is also an important autobiographical component. As a boy, Fabre had two pets, two little turtles named Janneke and Mieke, and both beasts, moreover, had been featured in a number of the artist’s performances. One of these took place in 1982: the protagonist is Mieke and she is fed a piece of tomato, which, however, has a skin that is too smooth for her to grasp with her beak. “Yet,” Fabre had written on July 27 in a note in her diary, republished in the catalog of the 2014 Lyon Biennial, “Mieke never gave up. And I noticed how she finally pushed the tomato toward a corner. Once it was stuck, she could hold it with her head and, pulling it a little toward herself, she would help herself with the shell to peel it. At that point the Greek heroine’s feast would begin. She would eat half a tomato in a single session.” Fabre was in the habit of showing the footage to the actors and dancers in his theater company so that they could learn from the animal’s behavior: ingenuity, inventiveness, knowledge of one’s limits, concentration, perseverance, optimization of movements and time. The same qualities that enabled Jan Fabre to become one of the most important artists on the contemporary world stage.

“Fabre,” wrote scholar Anne Perez as early as 1997, in a biography of Fabre that appeared in a large volume devoted to Flemish and Dutch artists from van Gogh onward, “is not an easy artist: he is stubborn, fond of double-meaning provocations, refuses all compromises, and analyzes in detail his conflicts with society through his use of language and through the way he constructs his texts. He is also vain: in his multimedia works he gives vent to his precise ideas about art history, within which moreover he is eager to carve out his own niche. The fact that this has, in the meantime, already happened is indicative of the keen interest in his work.”

|

| Jan Fabre, Searching for Utopia (2003; bronze). Ph. Credit Dirk Pauwels. Copyright: Angelos bvba |

|

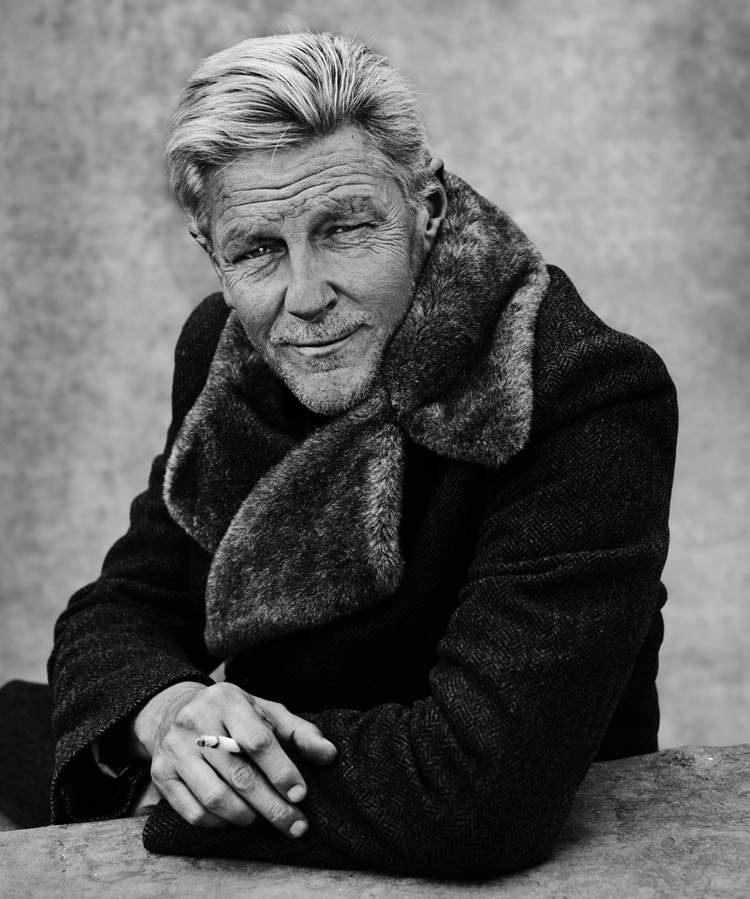

| Jan Fabre. Ph. Credit Stephan Vanfleteren. Copyright: Angelos bvba |

That stubbornness was as much a substantial trait of Jan Fabre’s art as it was of his temperament had been clear ever since he began to appear on the art scene in Belgium. The artist was born in a working-class neighborhood of Antwerp, Seefhoek, to a family of limited economic means but boundless intellectual means: his uncle Jaak was an actor, and his father Edmond had ambitions to become an artist, so much so that he had even enrolled at the Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten van Antwerpen, the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, but had been forced to give up finishing his studies because he could not afford them, and had had to content himself with finding work as a municipal gardener. But he never failed to pass on all his passion for art to Jan: when the artist was still a child, the two of them went together to museums to see the works of the great Flemish masters of the past, and it is quite safe to assume that from those moments Fabre had developed his passion for art history. His mother Helena Troubleyn also played a key role in his education: in his recent monograph on Jan Fabre, Jean Blanchaert recalled how Helena was used to tell Jan stories from the Bible, read him Baudelaire and Rimbaud, and make him listen to the music of Georges Brassens, Edith Piaf and Jacques Brel. “I owe a lot to my parents,” Jan would later say in an interview. “My father used to take me to the Rubenshuis, and he taught me to appreciate painting. My mother translated French literature into Flemish for me. My interests in words and images come from them, and drawing and writing are the foundations of my work. I think as I write, and I draw as I think.”

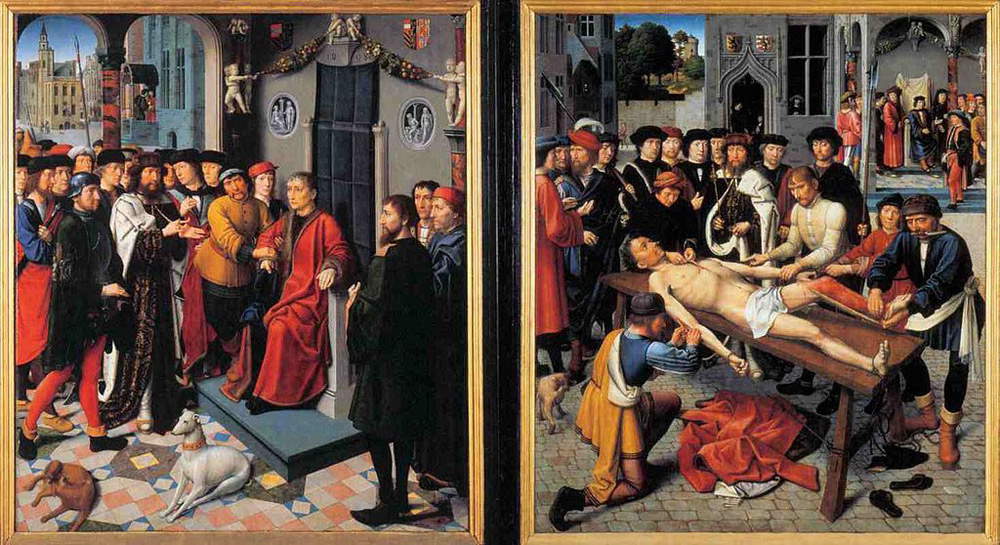

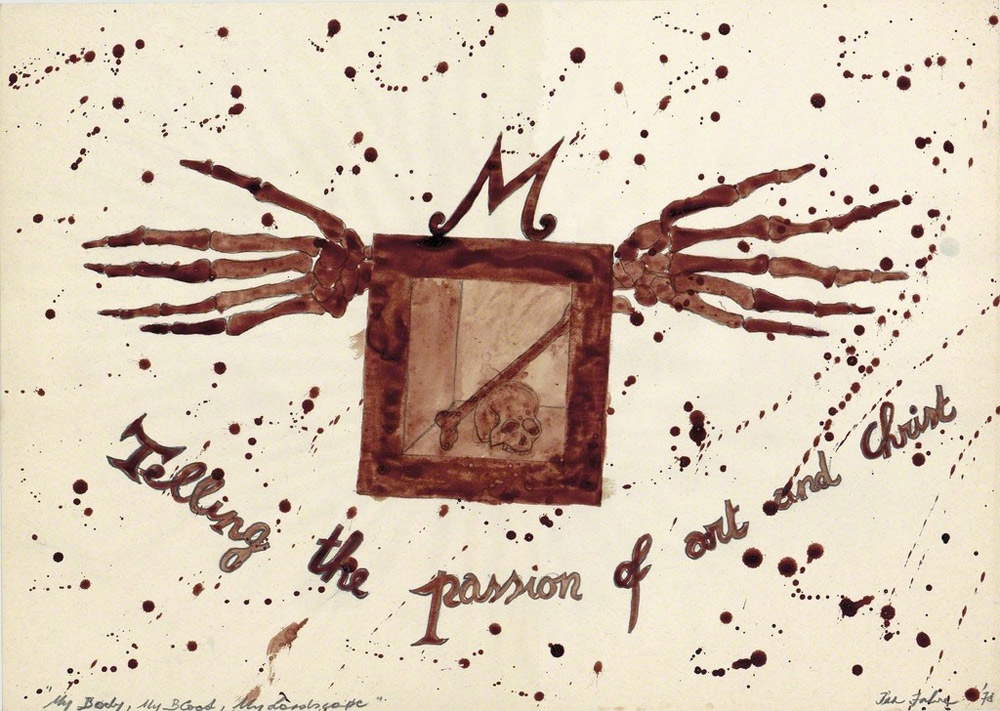

All these experiences add up in his early works. In 1978, in his twenties, he went to Bruges, where he visited the Groeningemuseum and admired the works of the great masters of Flemish art history. There are some paintings that shock him: one of them is the Judgement of Cambises, a 1498 diptych by Gerard David that depicts the condemnation and execution, by flaying, of Sisamne, one of the judges of Cambises, king of Persia, son of Cyrus the Great. This is a very violent painting in each of its two scenes: on the left we see Sisamne listening in astonishment and helplessness, but with great dignity, to the sentence passed against him, and on the right we see him tied to a plank while his torturers are already turning on him. Fabre is at once scarred by the sight of this painting and fascinated by the potential that the body can take on as much as an object of investigation and as the very instrument of artistic practice. He therefore decides to cut himself and draw with drops of his own blood: thus are born the works in the series My Body, my blood, my landscape. Fabre is convinced that art is something that comes from the body, and consequently bodily fluids become a technical medium: there are his drawings created not only with blood, but also with tears, with semen, with sweat, with urine. Experiments that a few years earlier had also been implemented by Andy Warhol (although they constitute one of the lesser-known strands of the American genius’ production). One of the works in the series My Body, my blood, my landscape is titled Telling the Passion of Art and Christ and depicts a sort of reliquary complete with a Marian symbol from which two skeletal hands sprout out and which contains a skull and a bone: elements that will be recurrent in the entire production of Jan Fabre, who has always looked at religion with interest.

|

| Gerard David, Judgement of Cambises (1498; oil on panel, 202 x 349.5 cm; Bruges, Groeningemuseum) |

|

| Jan Fabre draws with blood during the performance My Body, my blood, my landscape. Copyright: Angelos bvba |

|

| Jan Fabre, Telling the passion of Art and Christ (1978; pencil and blood on paper, 48.7 x 55.8; Private collection) |

And the culmination of this interest was, in 2015, the entry into the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp (which had not acquired new works of art since 1924) of one of his monumental works, The man who bears the cross (“The man who bears the cross”), another bronze in which a man is seen (a further self-portrait of the artist, who, however, this time merged his own features with those of his uncle: it has been said, after all, that vanity with Jan Fabre becomes art) who, in the palm of his right hand, balances an enormous cross. The Cathedral is home to several works by Pieter Paul Rubens, including a very powerful crucifixion where we witness, in a whirlwind of vigorous bodies and dismayed onlookers, the raising of the cross to which Jesus was nailed. Thus, on one side of the Cathedral we observe the sacrifice of Christ who subjected himself to the tortures of the cross in order to redeem humanity, and on the other side tohumanity itself, represented by the man carrying the cross (who takes on the connotations of Fabre and his uncle but who in reality, by the artist’s own admission, could be anyone) who questions, for a thousand reasons, this sacrifice: and this reflection involves a necessary search for a point of balance among the thoughts that clutter the minds of those who, believer or not, try to reason about the figure of Christ. “Do we believe in God, or do we not? The cross on the palm is the symbol of this question,” Fabre said.

It is a work of extraordinary modernity, not least because of the fact that Jan Fabre is not a believer: he calls himself a “spiritual sceptic” (and The Spiritual Sceptic was also the title of the exhibition held at the At the Gallery space in Antwerp between late 2014 and early 2015, and as part of which The man who bears the cross was exhibited for the first time). “Spiritual skeptic” because his way of reasoning prevents him from remaining constrained within the rigid schemes of any religion, but at the same time the artist is aware that human life is animated by spiritual, transcendental drives. Nevertheless, Antwerp Cathedral has had the insight and the merit of welcoming a work that does not provide answers, does not in any way comfort the faithful, who often do not admit truths that do not correspond to the one he expects: on the contrary, The men who bear the cross is a work that fuels questions and doubts. Indeed: it makes itself a symbol of doubt. Doubt, however, is a positive virtue: it always involves a search, and consequently a confrontation, since in order to attempt to find an answer to one’s questions (or, at the very least, that point of equilibrium that the man in the coat holding the cross seems to seek) it is necessary to place oneself in relationship with one’s neighbor. There is no burden to be borne (as there is in the nineteenth-century Stations of the Cross by Louis Hendrix and Frans Vinck, which the visitor to the Cathedral sees behind Fabre’s work), there is no suffering, there are no faithful succumbing under the weight of a divine authority that crushes them oppressively: there is, on the contrary, that lightness which is moreover typical of Belgian art and which is fundamental to having a soul willing to accept more truths, to relate points of view, to reflect on what others think, to try to understand the motives of one’s neighbor. The poised cross thus becomes a symbol of openness and dialogue, sending a message of strong and urgent relevance.

And Fabre, moreover, is preparing to return to a church in Antwerp. This time, however, in the church of St. Augustine, which from August 2018 will host three of his altarpieces: the project will be part of the Jan Fabre and the Monumental Churches program (which in turn is part of the Antwerp Baroque 2018 poster. Rubens Inspires), through which the spaces left empty by the three works by the great Flemish artists once on the altars of the naves (Rubens’ Holy Family with Saints, Jacob Jordaens ’ Martyrdom of St. Apollonia, and Antoon van Dyck’sEcstasy of St. Augustine ) and now musealized at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, will be filled precisely by Fabre’s works.

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, Crucifixion or Raising of the Cross (1610; oil on canvas, 462 x 341 cm; Antwerp, Cathedral) |

|

| Louis Hendrix and Frans Vinck, Way of the Cross, eighth station: Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem (1864; oil on canvas; Antwerp, Cathedral) |

|

| Jan Fabre, Man who bears the cross (2015; bronze, 394 x 200 x 100 cm; Antwerp, Cathedral). Ph. Credit Attilio Maranzano. Copyright: Angelos bvba |

|

| Man who bears the cross by Jan Fabre in Antwerp Cathedral. Ph. Credit Attilio Maranzano. Copyright: Angelos bvba |

|

| Man who bears thecross by Jan Fabre in Antwerp Cathedral. Ph. Credit Attilio Maranzano. Copyright: angelos bvba |

|

| Detail of Man who be ars the cross by Jan Fabre, with Stations of the Cross by Louis Hendrix and Frans Vinck behind. Ph. Credit Attilio Maranzano. Copyright: angelos bvba |

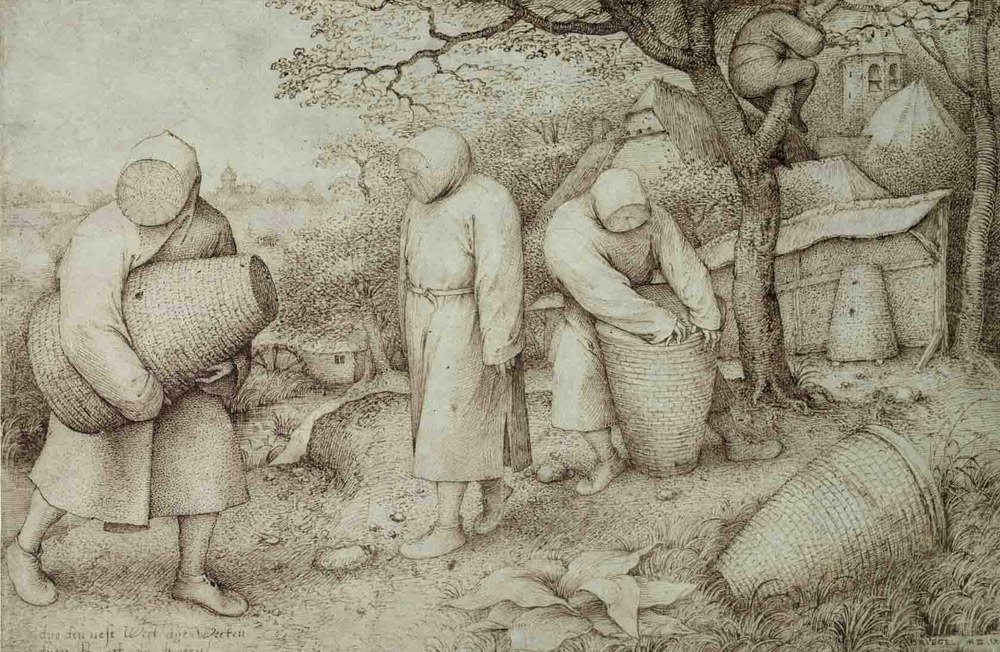

From the great Flemish masters, Fabre also borrowed some technical solutions. Jan van Eyck, for example, used a mixture that, in addition to pigments, included calcined bone dust to prepare the colors. And it is precisely bones that have become one of the most typical materials in Jan Fabre’s production. His 2017 Venetian solo show, staged in the premises of theAbbey of St. Gregory, featured his famous Monks: eerie sculptures made from human bones that reproduce the clothes of monks, following the lines of the body, but hollow inside. They refer directly to the Beekeepers of Pieter Bruegel the Elder: thus, the skeleton comes out of the body and goes to create a kind of armor, around a void that represents the pure spirit of the human being (monks, after all, are men who have decided to cultivate their spiritual dimension). This reversal of perspective, with the skeleton brought outward and thus, for Fabre, such as to make the man of the future immune to injury, is symbolic of a renewed feeling that can lead the whole of humanity to change its way of seeing reality. But as is the case with almost all of Jan Fabre’s works, Monks also conceals an underlying ambiguity well summarized by Giacinto Di Pietrantonio, curator of the aforementioned exhibition in Venice: “it is the bones that resist time and preserving themselves over the millennia allow us to know who we are, where we come from and where we are going in the birth-life-death cycle. [...] Bones, then skeleton, which, when the flesh disappears, remains in our representation, even figuratively speaking, and which, therefore, represents the ultimate state of existence after death and its last witness of reality. However, like glass, bones are not indestructible. Like glass, bones break denoting our fragility and transience.”

And the theme of the transience of living beings is a constant thread in the research of Jan Fabre, whose production abounds with memento mori that have their roots in the great medieval Triumphs of Death, the mournful seventeenth-century allegories, and Ensor’s macabre fantasies. In Venice, the Skulls series had been installed along two corridors of the Abbey of San Gregorio: sixteen glass skulls (another material symbolic of fragility, but also ambiguous, given its simultaneously solid and liquid nature) that held as many animal skeletons in their teeth and that harked back to other similar works the artist has executed in the past. Another room was entirely occupied by the installation The Catacombs of the Dead Street Dogs ("The Catacombs of the Dead Street Dogs"), a further vanitas in which real dog skeletons are arranged on the floor, or attached to long streamers hanging from the ceiling, in a room containing the remains of a party: a grotesque carnival like those that populate the paintings of 16th-century Flemish and Dutch painters, a modern danse macabre that strikes the visitor with disruptive force because of its strong allegorical charge and the way it expresses it. Even what is perhaps Jan Fabre’s most famous work, L’homme qui mesure les nuages (“The Man Who Measures the Clouds”), in a way reflects on death.

It is a bronze sculpture, depicting a man on a ladder, holding a tape measure, caught in the act of reaching out toward the sky to take measurements of clouds. On a first level, it is a quotation from the 1962 film The Man from Alcatraz, which tells the story of Robert Stroud, a criminal sentenced to life in prison who became a famous ornithologist: in the film, at the moment he is released from prison, Stroud manifests his intent to “go and measure the clouds,” well aware of the impossibility of the undertaking. It is a metaphor for the work of the artist, who, measuring himself daily against his own limits, reminds one of the scientist who measures himself against the limits of human knowledge, and who enacts the feat of telling the world his vision, of trying to express through art what is difficult to express, of becoming the interpreter of a dream. It also represents a reflection on death in that the features of the face recall those of Jan’s brother, Emile, who died prematurely at a young age: the work is thus cloaked in a moving melancholy.

|

| Jan Fabre, Monk (Umbraculum) (2001; human bones and wire, 169.8 x 92.3 x 66.3 cm; Istanbul, Ali Raif Dinçkök Collection). Ph. Finestre Sull’Arte. Copyright: Angelos bvba |

|

| Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Beekeepers (1568; pen and ink on paper, 20.3 x 30.9 cm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

| Jan Fabre, Skull with squirrel, from the Skulls series (2017; Murano glass and squirrel skeleton, 53.6 x 23.8 x 25.2 cm; Private collection). Ph. Pat Verbruggen. Copyright: Angelos bvba |

|

| Jan Fabre, The Catacombs of the dead street dogs (2009-2017; Murano glass, stainless steel and dog skeletons, dimensions variable). Ph. Pat Verbruggen. Copyright: Angelos bvba |

|

| Jan Fabre, Man measuring clouds (1998; bronze). Ph. Credit Wolff & Wolff. Copyright: Angelos bvba |

All of Jan Fabre’s work, after all, is marked by a romantic and moving vein. His is a constant search for beauty, although for him beauty is not, in a simple and vulgar way, the mere contemplation of an object that arouses aesthetic pleasure. Beauty for him is something deeper. Fabre calls himself a “warrior of beauty,” and he has extended the same title to the actors in his theater company: they, too, are warriors of beauty. “An actor I call a ’beauty warrior,’” he said in an interview, "is someone exceptional, because he defends beauty with all his strength. I think beauty warriors have to approach their work very seriously [...]. Beauty warriors must keep searching for the terra incognita, the places where they lose their landmarks, and also themselves, so as to rediscover their roots and enter a new level of awareness. Discovering these states is synonymous with the search for beauty. There is a Flemish word, redeloosheid, which could be translated literally as ’unreasonableness,’ and which includes the concept of reason and its opposite. This unreasonableness comes from within: it is the domain of unrestrained anarchy, passion and love."

Beauty, for Fabre, is outside ideology and aesthetics. The beauty of aesthetics is a beauty “that can be manufactured,” to use his own words. But the beauty Fabre seeks is independent of any preconstituted scheme. It is the search for spaces and possibilities between opposites: life and death, past and present, reality and fiction, body and spirit. It is the very co-presence of these opposites. It is the way in which his works manage to animate opposite feelings in those who admire them. It is a yearning for freedom.

Jan Fabre was born in 1958 in Antwerp, where he lives and works. After studying at the Institute of Decorative Arts in Antwerp, and later at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in the same city, he began in 1977 to make his first works and performances. His first exhibition, held at the Workshop 77 gallery in Antwerp, dates back to 1979. In 1984 he was called to the Venice Biennale, where he exhibited in the Belgian Pavilion. He then returned to the Venice Biennale on several occasions. Instead, his first Italian solo show was at the Centro Pecci in Prato in 1994, while his last two exhibitions in our country are “Spiritual Guards” (Florence, 2016) and “Glass and bone sculptures” (Venice, 2017). Throughout his long career, Jan Fabre has taken his works around the world, always sparking heated discussions around his works. Alongside his work as an artist, Fabre also works as a theater director and choreographer.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.