Italian-style heritage protection: Mutignano and the church of Our Lady of Consolation

The Abundance of Abandonment: Italy, it is now commonplace, has an endless cultural heritage, but perhaps outside the country very few know that not all of this heritage is usable, protected, intact. It would be fair to say that almost half of this heritage is abandoned and in ruins. Of course, someone may think of the destruction caused by recent earthquakes, but paradoxically these and other natural phenomena nowadays seem to affect heritage less: the famous vault of the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi, which collapsed in the 1997 earthquake, has been rebuilt with its frescoes, and in the historic center of L’Aquila, despite the slow pace of work, the National Museum of Abruzzo (partially) and at least three churches have reopened, although there is the other side of the coin witnessed by the towns affected by the 2012 Emilia earthquake where reconstruction seems yet to begin. The most serious damage is man-made. Nor is there any thought of forceful action here, since our country is not currently affected by violent wars.

The origin is psychological: ignorance and disinterest, mixed with the loss of various pieces of popular culture(first and foremost, religious tradition, with a series of devotions and festivals now forgotten, which were linked to churches for this reason considered important), have led to the turning away of eyes and care from entire buildings. Guilty of this are the ordinary citizens, who only in localities with a rich historical tradition sometimes move to defend neglected monuments. But from those ordinary citizens come the democratically elected ruling class, national and local, come the members of the Superintendencies, come all those who are part of bodies and institutions without primary cultural purposes but who find themselves managing a part of the heritage, for example, the Church.

Certainly the monuments that suffer from such neglect are those that are called minor only for the sake of communication needs, since in reality none are really so: so it will not be a Cathedral, in the central point of a city, that is in neglect, as much as an oratory in the alleys of the historic center or a former convent in the countryside. Paradoxically, the density of abandoned sites increases as the size of the locality decreases: a medium-large city certainly has a greater number of abandoned buildings, but a small town, gathered around its square and main building (the parish church) and with a municipal territory limited to the neighboring countryside, has many of them in close proximity.

The main cause is depopulation, which in turn is a consequence of a number of economic and social issues that cannot be discussed here: globalization, the allure of big-city opportunities, industrialization, a certain centralism somewhat in all areas of public life. All this has been done without respect for the particularism that characterizes Italy, united for only one hundred and fifty years; the territories of these small towns have become an area of exploitation for indiscriminate urban expansions and industrial projects, disintegrating their culture and doing nothing to improve their fortunes, while the young people, given these premises, have been piling up for decades now in the big cities (few by the way) and in the localities closest to them, some driven by a kind of rejection and forgetfulness of their origins, eager to chase thatambiguous progress that only in a few parts seems possible to achieve, others instead out of what can painfully be called a spirit of survival, having no other opportunity than to move away, with great discomfort, to have something to live on (and we are talking about the 21st century!).

Politicians have used cultural heritage for pure rhetoric, to make themselves look good in front of everyone, Italians and foreigners alike, and they have gamely leaned on those monuments that could best express an idea of well-being: it is consoling to see kilometer-long lines of tourists at the Uffizi Gallery, and then go and see how many Florentines go there and feel the museum as their home because it is an expression of their own culture.

Outside the usual large sites, which also have their problems, the situation becomes more and more bleak, until we reach as mentioned these small towns that are now losing their identity. The slowness of bureaucracy, in the Superintendencies and other institutions, is the icing on the cake.

Let’s take an example, of the very unknown ones, and almost forgotten by the local population itself. Driving up from the Abruzzo coast, on the dingresso driveway in Mutignano, no one would pay attention (and I don’t think the local kids would either) to a building covered in scaffolding, in an advanced state of disrepair, without even a sign to mark it, in short, inconspicuous compared to the modern houses, resplendent in their new plasters, that almost assault what is a church, dedicated to Our Lady of Consolation.

|

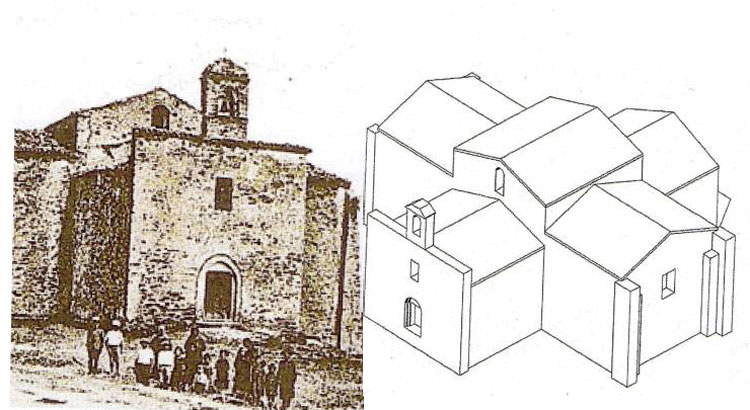

| Left, an old photo of the church of Our Lady of Consolation in Mutignano. Right, a floor plan of the original structure (images from www.lacittasottile.it) |

The reader will ask: but what is Mutignano? It is understandable that he does not know it, but we warn him that, even if he were to travel to the area, almost no one would direct him to visit it, overshadowed by the constantly publicized monuments of nearby Atri, the vibrancy of the coastal resorts below, and yes, even theignorance of those who should be in charge of cultural popularization and tourist management in the area.

Mutignano is now a hamlet of Pineto, a seaside town in the Province of Teramo of about 14,000 inhabitants. For centuries the town was one of the casali (hamlets) of Atri, the only one toward the sea along with neighboring Silvi. Both shared a strategic military importance vis-Ã -vis the main town: while the latter had to control and defend the underlying Porto di Cerrano, Atri’s commercial port of call, developing in this sense a seafaring culture alien to the dominant town and its territory, Mutignano was the castle in charge of defending from the eastern side Atri itself, which instead for the defense of the opposite side possessed a fortress within the walls. Mutignano was thus considered a kind of extra-urban extension of Atri and it is significant that, in the land registries, it was united with the eastern quarter of the city, the quarter of San Giovanni. Traces of this strong link remain in the two churches still existing in the historic center, San Silvestro and SantAntonio, where artists active in Atri (e.g., Andrea De Litio in the 400s) worked or re-proposed in simplified forms what is there in the capital. Also on a social level Atri and Mutignano, despite the autonomy obtained by the latter in the second half of the 1700s, maintained a close relationship, and almost as a natural consequence the beach at Pineto below is now the summer destination of Atrians. Pineto is a founding town: it came into being between the 1920s and 1930s on some land that the Filiani family, from Atri, owned on the stretch of coastline in the municipality of Mutignano. The new entity immediately became the municipal capital and grew rapidly thanks to the influx of people not only from the old municipal seat, not only from Atri, but also from nearby coastal towns such as Silvi and Roseto. With a small but significant difference from the latter. Beginning in the nineteenth century the towns of the Province of Teramo on the last hills before the sea began a rapid development close to the beach, now no longer marshy and malarial as it once was. The new urban agglomerations basically sprung up spontaneously and gradually, and people from the hills moved there, maintaining contact with the old town, which sometimes retained its municipal seat and whose name the new town took over, ensuring historical and cultural continuity. So it was in Silvi, so in Giulianova where the old town and the coastal part are practically one. Pineto, for the brief historical notes above, cannot be considered a natural expansion of Mutignano. The names are different, the patron saints different, and the heterogeneous character of Pineto’s early inhabitants created a new identity.

|

| View of Mutignano (from Panoramio) |

Mutignano, despite the fascination it may arouse in the small Pineto municipality for the historical evidence it possesses, is in fact seen and treated as a hamlet. Along the streets of the municipality, advertising signs with the large inscription Visitate Mutignano, installed about a decade ago and now so blackened as to go unnoticed, still make an appearance. In the old town, with a herringbone urban layout that runs between the parish church and Castellare Park (where the castle used to be), few residents remain. No one can be found even during the week of Ferragosto, when the whole area is packed with tourists. The local Protestant community, of which the pretty chapel on the Corso remains, had to join that of Giulianova because of lesiguities. The church of St. Anthony, a small Baroque jewel, is open only during conferences and concerts, which are certainly not continuous throughout the year. Slightly easier is to visit the parish church of St. Sylvester, whose openings have drastically decreased since the theft of several tablets of Andrea De Litio’s Renaissance altarpiece in 2006, a sign of the lack of adequate custody and protection. Many ancient buildings, despite skillful renovations in recent years, still show decidedly unsuitable parts of the structure.

The height of local disinterest in this small town is admired, as mentioned above, in the Church of Our Lady of Consolation. By now its state of neglect can be said to be historic. Whole generations have seen it this way, an almost familiar presence with those rundown walls and that slight bell gable overlooking the small field destination of the village children.

|

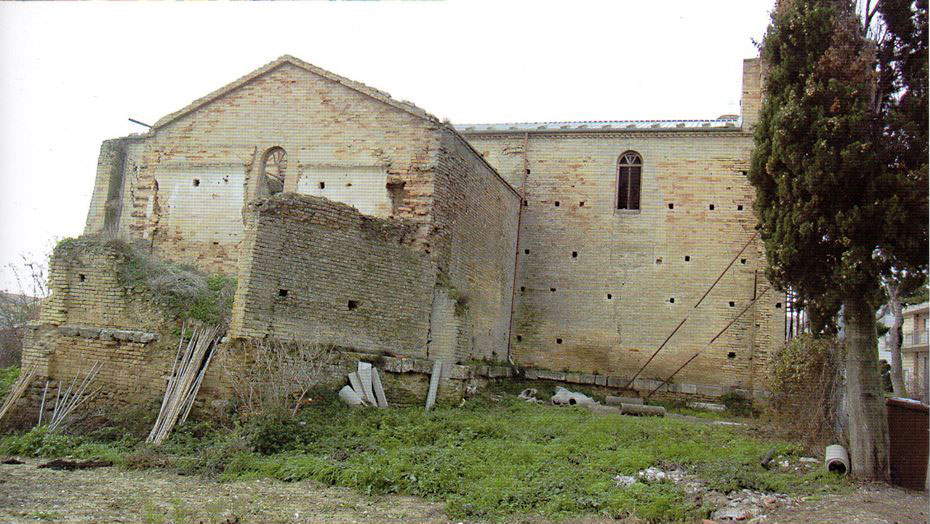

| Madonna of Consolation in Mutignano, current state of the facade (photo by Francesco Mosca) |

|

| Our Lady of Consolation in Mutignano, current state of the side (photo from www.lacittasottile.it) |

The church, founded in 1408 as stated in anepigraph transferred to the parish church (but it is not known whether it was founded on an earlier church), was important in the area both historically-artistically and religiously. Built outside the walls, like many Marian shrines (Santa Maria del Soccorso in LAquila, the Madonna di san Luca in Bologna, the Madonna dellImpruneta in Florence ), and with a Greek cross shape, of Byzantine derivation, one of the few such buildings in Abruzzo, the little church was the typical Cona, as rural churches built around a much revered sacred image (from Icona) are called in Abruzzo, so much so that the Madonna della Consolazione was also called Madonna della Cona by the people of Mutignano. The feast in honor of the Virgin was held on September 8 and saw a large attendance because of the possibility of earning a plenary indulgence, it is not known when instituted.

The problem of the church’s health had presented itself as early as 1924, reported by the area inspector for the Royal Superintendence of Rome and by the Municipal Administration, which for a few more years would be based in Mutignano. The structural damage found dated back several years, perhaps to the 1884 earthquake.

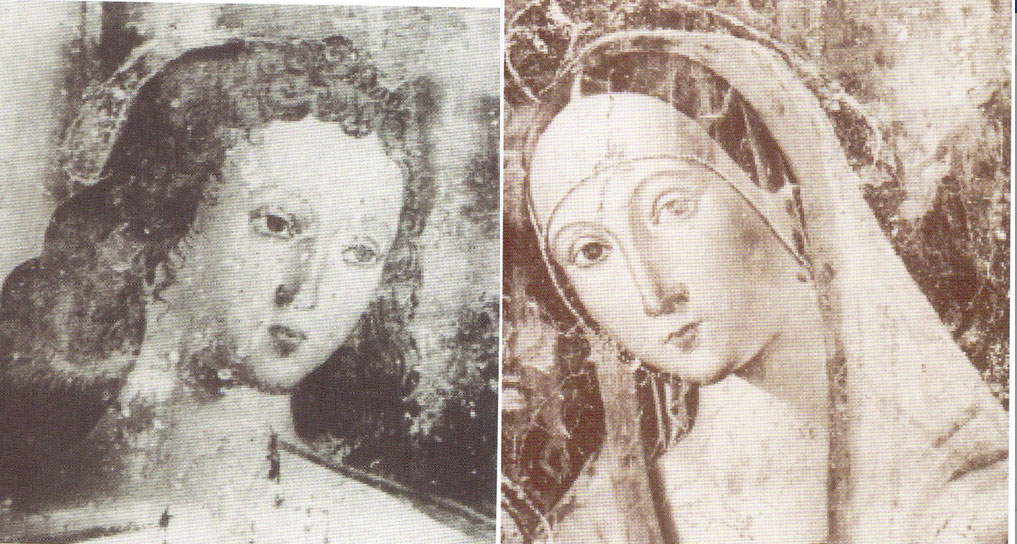

The report on the building brought attention especially to some frescoes, with two attached photos depicting St. Sebastian and the Madonna and Child, datable within the first two decades of the 1500s, by an Umbrian-Marchigiano painter very close to the manner of Bernardino di Mariotto of Perugia, active from 1502 to 1521 in San Severino Marche, who sought to combine in an easy and pleasing manner the late Gothic manners of Carlo Crivelli, the delicate style of the recently deceased local master Lorenzo dAlessandro and the innovations of Perugino and Pinturicchio. The same painter of the Madonna of Consolation probably worked in the church of St. Sylvester, where he frescoed a Madonna and Child between St. Reparata and St. Blaise.

|

| Photographs of Saint Sebastian and the Madonna and Child (details) from the 1924 report. |

|

| The fresco of the Madonna and Child between santa Reparata and san Biagio in the church of San Silvestro (photo by Sergio Scacchia) |

Influences from the Marche area must have been present in the area if one also looks at the large Pala degli Osservanti, now in the Museo Capitolare in Atri, executed by an anonymous southern master of higher stature than the Mutignano painter, who re-proposes in a personal style the various artistic trends circulating then along the Adriatic coast. For a better restoration of the building, it was recommended that the church floor, raised in 1749 to accommodate burials, be lowered so that more frescoes could be brought to light. But no intervention was put in place. From the photos of the period and the current appearance of the building, it can be assumed that architectural interventions were carried out without scruples of protection that heavily modified the church, perhaps due to another earthquake, the one of 1930: the facade was moved to where it is today, directly on the avenue, making what used to be the transept into a nave and raising the walls of this one, while the old presbytery was torn down.

|

| The Observant Altarpiece (Atri, Capitular Museum - photo by Gino Di Paolo) |

Also, during World War II, according to local people, it appears to have been used as a weapons warehouse. The church continued to be officiated until the 1960s, when decay was so advanced that the parish priest decided to close it due to unfit for use, thus decreeing the end of the September festival. Perhaps the priest sensed that this would not be resolved right away: everything salvageable was brought to the parish, the altarpiece (a 19th-century copy of Raphael’s Madonna Bridgewater ), some canvases from the first half of the 17th century including a Madonna of the Rosary, and finally a few votive offerings. The frescoes remained on the walls and to this day their fate is unknown.

Over the decades, the situation worsened, culminating in the damage caused by the 1984 earthquake, which especially undermined the stability of the roof (which in fact collapsed a few years later). The parish priest had thought of demolishing it, but the Pineto Municipal Administration bought it, without however initiating a recovery project. Santa Maria della Consolazione was destined to become in all a ruin to be studied for Archaeology, until in 1998 the Ministry of Fine Arts (modestly) intervened by constructing shoring and a temporary iron roof (except in the area of the original entrance), renovated over the years. The Superintendence in 2006 allocated 250,000 euros for restoration, a rather meager sum that, once again, did not translate into deeds. Local governments have always set themselves the goal of restoring Our Lady of Consolation, but to date its state is still that of a ruin, more than fifty years after its closure. In the last months of 2015 and early 2016, close agreements between the municipality, the region, the Diocese of Teramo Atri and a number of architects made it seem that work was imminent.

But as of today, early 2017, the church of Our Lady of Consolation in Mutignano is in its traditional state as a propped-up ruin. Who knows, perhaps it will remain that way forever. Then again, no one remembers it open, and so many churches have become notorious for their abandoned state, such as San Galgano in Chiusdino (Siena), or in Abruzzo Santa Maria di Cartignano near Bussi sul Tirino. Thus, as those churches lost their function due to a series of events and cultural changes in the area, this far more modest one will also be left there. Indeed, with its inconspicuousness, lack of notable artistic elements (but what it had is either relocated or will have been destroyed!), perhaps one day it will go under the bulldozers and a new house will appear in its place. Or they will expand the little field, which has already taken the place of the old presbytery.

Art historical reference bibliography on Mutignano

- Luisa Franchi DellOrto (ed.), Documenti dellAbruzzo Teramano, vol. 5, Dalla valle del Piomba alla valle del basso Pescara, Sambuceto (Ch), Poligrafica Mancini, 2001

- CARSA Editions, Unknown wonders of Abruzzo, vol. 11 The treasures of history, pp. 64 67, Sambuceto (Ch), Litografia Brandolini, 2006

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.