by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 03/11/2018

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

At the exhibition "Lorenzo Lotto. The Lure of Marche," the curator, Enrico Maria Dal Pozzolo, puts forward a suggestive hypothesis for a panel preserved in Recanati and so far assigned to an anonymous artist: is it the work of the young Lotto?

A “reasonable bet” and a “critical provocation that can only provoke discussion”: with such definitions, Enrico Maria Dal Pozzolo intended to present a new and suggestive attributional hypothesis for the Holy Family preserved at the Diocesan Museum of Recanati, and until February 10, 2019 exhibited in Macerata, in one of the rooms of Palazzo Buonaccorsi, for the major exhibition Lorenzo Lotto. The Lure of the Marche. According to the curator of the Marche exhibition, the painting could represent one of the first achievements of the young Lorenzo Lotto (Venice, 1480 - Loreto, 1557): however, it is necessary to proceed step by step, and retrace the history of the painting in order to better contextualize the important question that Dal Pozzolo has brought to the attention of critics.

The work, a panel painted in tempera and oil, formerly kept at the Recanati Cathedral, and to be exact in the chapel of the Antici family, of ancient Recanati nobility, was first reported in 1711 by Diego Calcagni, a local scholar, who in his Memorie istoriche della città di Recanati cited the picture as a “very ancient” painting that “represents Giesù, Maria e Giuseppe.” The three figures appear behind a classical archway and lean out over a balustrade covered by a carpet embroidered with fine oriental geometric patterns. The Madonna tenderly clasps to herself, resting her left hand on top of her right, the chubby Child who kicks gently and looks up, while St. Joseph, holding on to his own staff as per the usual iconographic topos, scrutinizes the scene from above. A first detailed analysis of the state of preservation of the panel dates back to 1928, when the Recanati art historian Irnerio Patrizi mentioned it in one of his works, Le grandi orme dell’arte del Quattrocento in Recanati, describing it in these terms: “it is painted on a solid poplar board reinforced by two crosspieces, recently sawn on the vertical sides and in the lower side; it has the thickness of 2 centimeters. The imprimitura, which appears at the edges, is of a general reddish color; the technique is that of tempera; peeling appears here and there on the surface and deteriorated due to various causes, including the superimposition on the head of the Virgin; the St. Joseph, if one excepts a few curls of the beard, would be said to have been completely repainted.”

|

| Venetian-Lombard painter of the late 15th century (Lorenzo Lotto?), Holy Family (1495-1500; tempera and oil on panel, 75 x 50 cm; Recanati, Museo Diocesano) |

|

| Holy Family, detail of Madonna and Child |

|

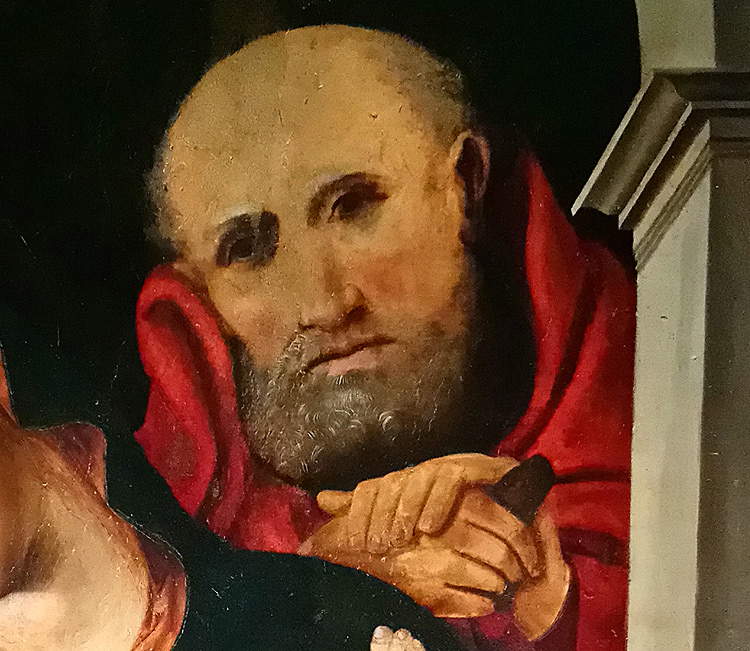

| HolyFamily, detail of St. Joseph |

This is a painting of clear Mantegna ancestry: the relationship, in particular, is with the moving Madonna of Humility by Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo, 1431 - Mantua, 1506), which in 1992 David Landau called “unquestionably the most beautiful print of the Italian Renaissance and one of the most touching Madonnas with Child in the history of art.” but of which we also know of a pen drawing with a tempera and gold-painted background that Lionello Puppi recently, on the occasion of an exhibition held in Padua in 2006, wished to attribute to the hand of the Paduan master, and which he called Madonna of Tenderness. In Mantegna’s Madonna, the Virgin, seated on the ground as per the iconography of the Madonna of humility, envelops the Child with a warm and soft embrace, lightly rubbing her face on his: in the face of such sweetness little can even the roughness of Mantegna’s sign, which does not make one of the most delicate and intimate scenes of the Renaissance any less lyrical. The pose assumed by the Virgin is the same as that seen in the Recanatese Holy Family, so much so that at the Macerata exhibition the two works were displayed side by side: in particular, of the five known exemplars of Mantegna’s Madonna, the one from the Biblioteca Antica del Seminario Vescovile in Padua arrived in the Marche.

Mantegna’s work is supported, “in all probability,” Francesco De Carolis, by “an invention that the artist elaborated to be translated exclusively in print, relating several aspects usually elaborated separately”: for example, it is the only work in which Mantegna treats the iconographic theme of the Madonna of humility, as well as the only case in which the Child appears in his mother’s arms while lying down (usually such a posture was reserved for works in which the infant Jesus was made to lie on the ground).

The Madonna of Humility may not, however, be the only Mantegna reference in the Recanati tablet. The motif of Mary brushing her son’s face with her cheek also animates the famous Madonna and Child now in the Poldi Pezzoli Museum: in the Milanese canvas, a work in which Mantegna still touches unusual heights of intense lyricism and unexpected sentimental finesse (as well as the only one, of those seen so far, in which the Child sleeps), it is still the mother’s gentle caresses that are the painting’s leading element, and this starring role is all the more evident if one notices the right hand, rendered with a masterful foreshortening of perspective. But that’s not all: as in the Madonna of Humility and Recanati’s Holy Family, the Virgin’s hands are present and alive, and the viewer can almost imagine her fingers sliding to caress the Child. But the same cannot be said of the eyes: in all three paintings, Mary’s gaze is absent, almost lost in emptiness, because her mind is already prescient of the suffering to which Jesus Christ is destined. Given the stylistic and formal characteristics, and given the conceptual proximity of the three works, since the beginning of the twentieth century, that is, since the Holy Family began to raise the interests of critics, the Diocesan Museum panel has always been ascribed to the Mantegna sphere, if not to Mantegna himself, as Irnerio Patrizi himself believed. Indeed: in the file on the painting in the Macerata exhibition catalog (which obviously traces a precise, punctual and complete outline of the critical history of the work), Enrico Maria Dal Pozzolo recalls that the scholar Francesco Filippini hypothesized, without concrete evidence, however, that the painting had been executed by Mantegna “about 1492, for Fra Giovanni Battista Spagnoli, a Mantuan, learned humanist and poet, beatified by the Church, who was a friend and admirer of Mantegna and celebrated him in his verses. In one of his poems, the poet recalls a vow, made by him to the Virgin Loretana, to offer a painting, and precisely a Holy Family, to implore healing from a serious illness.” And for several decades, the attribution to Mantegna was never questioned (only Berenson, in 1936, compiling the list of paintings in his Italian pictures of the Renaissance, identified the work as a “c[opy] of lost Mantegna,” that is, a copy of a lost original by Mantegna).

|

| Andrea Mantegna, Madonna and Child (1480-1490; burin on paper, second state, 240 x 240 mm; Padua, Biblioteca Antica del Seminario Vescovile) |

|

| The Holy Family and Madonna and Child at the exhibition Lorenzo Lotto. The Lure of the Marche |

|

| Andrea Mantegna, Madonna and Child (c. 1490-1500; tempera on canvas, 45.2 x 35.5 cm; Milan, Museo Poldi Pezzoli) |

In any case, the stylistic motifs discussed above were not the exclusive prerogative of the great Venetian painter: in fact, his invention was so successful that it attracted legions of artists who decided to replicate or reinterpret it in their works (and this is certainly no coincidence: for Mantegna, printing was a new and formidable means of circulating his ideas). This is the case, for example, with Domenico Morone (Verona, c. 1442 - 1518), an artist who in the early stages of his career had strong debts to Mantegna’s art, and who drew on the master’s print (cutting the figure of the Madonna at half-length) in an early 16th-century panel now in the Museo di Castelvecchio in Verona. One might then recall a painting by Francesco Bonsignori (Verona, 1460 - Caldiero, 1519), who in his painting, now in the National Gallery in London, wanted to introduce first the parapet in front of the Virgin and Child and, again first, inserted the figures of four saints on either side of the two protagonists thus going on to populate the scene with characters unrelated to the moment of intimacy that Mantegna had wanted to depict. Bonsignori’s is, moreover, the painting to which the Holy Family of Recanati comes closest. It should also be added that, in the Recanati panel, there are also some elements that would distance the work from a strictly Mantegnaesque sphere: wishing to gloss over the Saint Joseph, which because of repainting is too compromised to provide an acceptable term of comparison, observing the Madonna and Child one cannot help but notice a softer mark than that of Mantegna and his followers, as well as some details of the Virgin’s face (the cut of the eyes, the complexion, the long straight nose, the eyebrow arches) that would even bring the work closer to the sphere of the Leonardo painters, so much so that in 2005 Giovanni Agosti attributed the work precisely to an unspecified Leonardo painter.

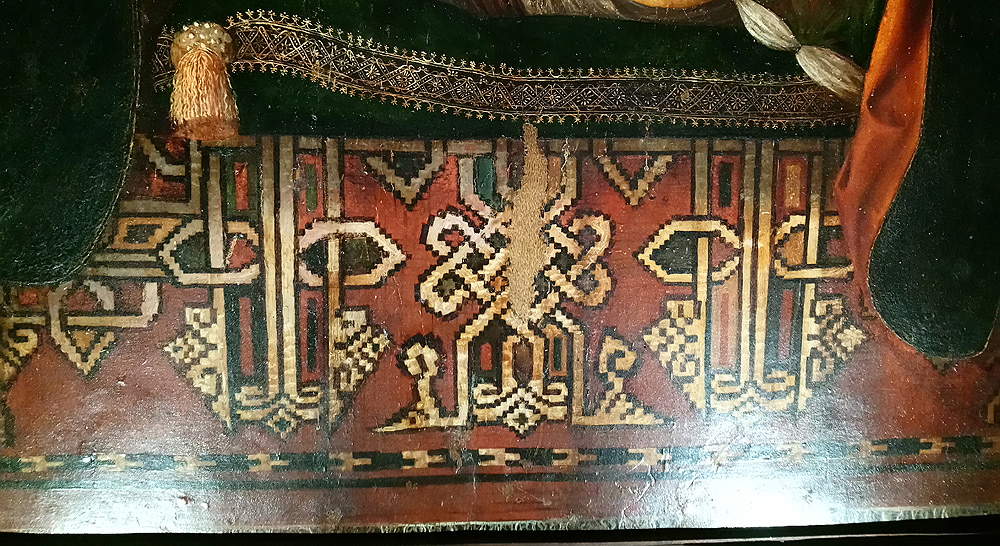

It is then necessary to devote some attention to the detail of the oriental carpet laid on the balustrade: it is a detail that denotes a close proximity of the author of the Holy Family to Venetian painting of the fifteenth century. Carpets like the one on the Recanati panel are in fact found in many works from 15th-century Venice: In a work by Vittore Carpaccio (Venice, c. 1465 - c. 1525), the Birth of the Virgin, which in ancient times was part of the cycle of the Stories of the Virgin that decorated the Sala dell’Albergo in the Scuola di Santa Maria degli Albanesi in Venice and is now instead in the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, on the foreground parapet that delimits the scene we find resting precisely a carpet, stretched halfway horizontally, exactly like that of the Holy Family.

Enrico Maria Dal Pozzolo’s “provocation,” according to which we might begin to seriously consider the idea that the Holy Family of Recanati might be anearly work by Lorenzo Lotto, is meanwhile justified on the basis of the similarities with Lotto’s early paintings, starting with the earliest known dated work by Lotto, the Madonna and Child with St. Peter Martyr of 1503 kept at the National Museum of Capodimonte: the curator of the Macerata exhibition identifies the “rather Bellinian” way of defining the hands as a common feature of the Marche and Neapolitan works. The use of light is then juxtaposed with what we can appreciate in the Portrait of a Young Man from the Carrara Academy in Bergamo, which we can consider Lorenzo Lotto’s earliest known work: it is a painting from around 1500, made when the artist must have been in his early twenties or so. Again, a revealing detail could be precisely the carpet in the foreground mentioned just above: it is not breaking news that Lorenzo Lotto loved carpets very much, so much so that a number of specific studies have even been devoted to the subject, one in 1998 by Rosamond E. Mack and one in 2016 by David Young Kim. “Lotto’s engagement with carpets in his works,” Kim wrote in his essay Lotto’s Carpets: materiality, textiles, and composition in Renaissance painting (the translation from English is by the writer), “was so profound that a type of sixteenth-century Turkish carpet pattern became known as a Lotto carpet.” Carpets bearing the artist’s name, Kim explains, “generally feature interwoven yellow arabesques, octagon, diamond or lozenge shapes on a red ground. The edges often contain blue intertwining zigzags.” Similar carpets are found in several paintings by Lorenzo Lotto (one of the most beautiful is the one that appears in the Portrait of Giovanni della Volta with his wife and children, at the National Gallery in London), but the one we find in the Holy Family is also an excellent example of a “Lotto carpet.”

|

| Domenico Morone, Madonna and Child (ca. 1500-1515; panel, 35 x 43 cm; Verona, Museo di Castelvecchio) |

|

| Francesco Bonsignori, Madonna and Child with Four Saints (c. 1490-1510; oil on canvas, 48.3 x 106.7 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Vittore Carpaccio, Birth of the Virgin (1504-1508; tempera on canvas, 126 x 128 cm; Bergamo, Accademia Carrara) |

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, Madonna and Child with Saint Peter Martyr (1503; oil on panel, 55 x 88 cm; Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte) |

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1500; oil on panel, 34.2 x 27.9 cm; Bergamo, Accademia Carrara) |

|

| Lotto carpet, from Anatolia (16th century; wool, 162 x 109 cm; Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art) |

|

| Holy Family, detail of the carpet |

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, Portrait of Giovanni della Volta with wife and children (1547; oil on canvas, 104.5 x 138 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

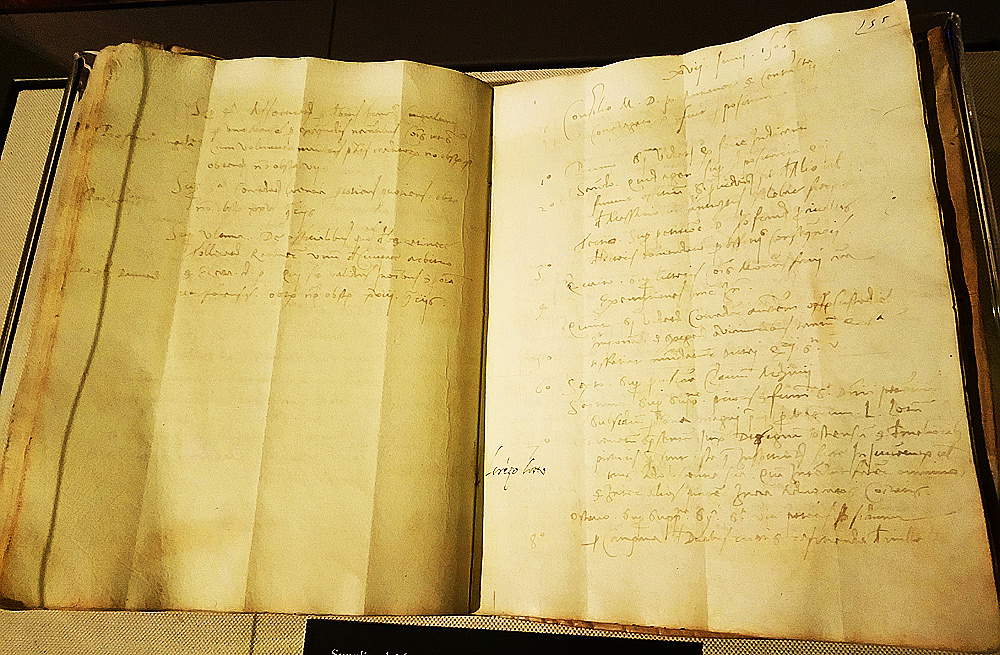

| Supplication of the Dominican friars of Recanati for funding for Lorenzo Lotto’s polyptych (Recanati, June 17, 1506; Recanati, Archivio Storico Comunale, Annales, vol. 80 (1506), cc. 55r-56r) |

|

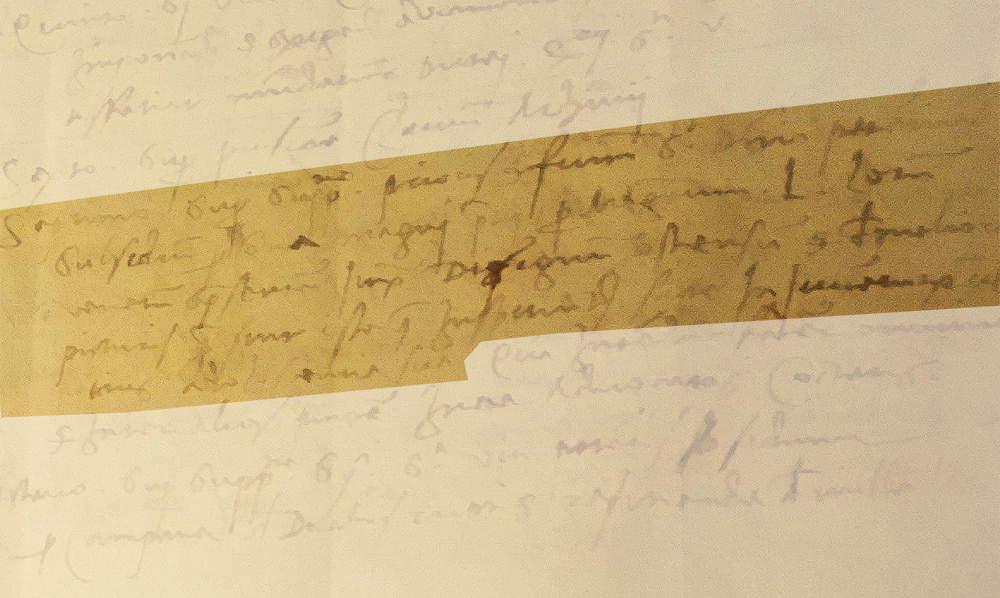

| The sentence mentioning Lorenzo Lotto’s youthful works present in Recanati: “Super supplicatione prioris fratrum S. Dominici petentis subsidium pro cona magni pretii per magistrum L. Lotum Venetum construenda iuxta designum ostensum et melioribus picturi, que sintiste que inspiciuntur facte in iuventute vel potius in adolescentia sua.” |

There are then reasons that could be deduced, according to Dal Pozzolo, from the analysis of the documents. More in detail, in the supplication of the Dominican friars of Recanati for the financing of the polyptych of San Domenico, dated June 17, 1506 (and also on display at the Macerata exhibition), reference is made to some works that Lorenzo Lotto is said to have painted precisely in the Marche village “in iuventute vel potiut adolescentia sua” that is, “during his youth or rather during his adolescence” (as Francesca Coltrinari explains in the exhibition catalog, at the time “adolescence” was legally fixed between the ages of fourteen and twenty-five, and “youth” came later). “The context of the sentence,” says Dal Pozzolo, "leads one to believe that we are dealing with work done at an age perhaps imaginable about seventeen to eighteen years old, thus - considering that in 1546 it was defined as about sixty-six - around 1497-1498 [...]. We would therefore be in a phase just before the one in which his first work that has come down to us seems to fall: the Portrait of a Young Man from the Carrara Academy in Bergamo [...], a work characterized by a very strong Antonello accent, but with a use of light and ductus that are not incompatible with the Marchesan panel." In addition, a further element that could support the attributive hypothesis refers us to Lorenzo Lotto’s first known patron, namely Bernardo de’ Rossi, bishop of Treviso of whom Lorenzo Lotto executed a splendid portrait now housed in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte: Rossi’s passion for Andrea Mantegna is well known, and probably, Dal Pozzolo suggests, the prelate decided to avail himself of the services of the young Venetian painter precisely because of his proximity to the manner of the Paduan.

Certainly, against such a fascinating hypothesis play the absence of certain documents, the fact that the known history of the Recanati panel begins very late, the scarcity of information on Lorenzo Lotto’s youthful years, the absence of references that can be traced back with certainty to the Holy Family, and the lack of Lotto’s works that can incontrovertibly refer to the same period. There is, however, the “condition of having to visualize the mystery” of Lorenzo Lotto’s beginnings, Dal Pozzolo explains. And to this end it was thought to introduce the Holy Family, a work known but so far never connected to Lotto’s inspiration, as a work that could be assigned to the hand of the Venetian master. This has been done deservedly without clamor, avoiding advancing Lorenzo Lotto’s name without admitting arguments and without question marks: in essence, rather than asserting that the Holy Family is certainly a new Lorenzo Lotto, it has been emphasized that it is not possible to exclude Lotto’s authorship. Certainly there is much material to discuss, and much to still study.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.