Is the great Pan dead? The death of Eros, the spectacular new work by Bertozzi & Casoni.

“When you are in Palodes, announce that the Great Pan is dead.” A voice rises from the island of Paxos that stuns all the passengers on the ship: it is directed to Thamus, the Egyptian helmsman. On the ship people wonder if they should disregard the order: the announcement of the death of a god would wreak havoc. It is left to the wind to decide: if there is a breeze at Palodes, Thamus will pass over the shores in silence. If there is becalmed, the announcement will be reported. At Palodes there is not even a whisker of wind. The sea is still. So Thamus moves to the stern of the ship and shouts toward land, “Great Pan is dead.”

Pan’s death, recounted in Plutarch’s Sunset of the oracles , remains one of the most exciting enigmas in classical literature. He is the only god whose death is recounted by an ancient source. We are still not sure what Plutarch meant by putting the hallucinating anecdote into the mouth of the historiographer Philip. The great Pan, the god of the woods, the god who lives in nature, the god who expresses vitality, instincts, natural impulses, is no more. How did he die? Bertozzi & Casoni imagined him hanging from a chandelier in Capodimonte, in their most recent work, a troubled work that took almost a quarter of a century to be finished and exhibited to the public. We see it after a descent into the bowels of Imola’s Rocca Sforzesca. Within the cold walls of the fortress that was at the center of fierce battles in the late 15th century. Conspiracies, wars, a siege. Then in the year 1524 it became a dreary prison and remained so until a few decades ago. Common criminals, thieves, murderers, political prisoners, anti-fascists. The eyes of who knows how many that rested on the stones of the Rocca before they died out altogether.

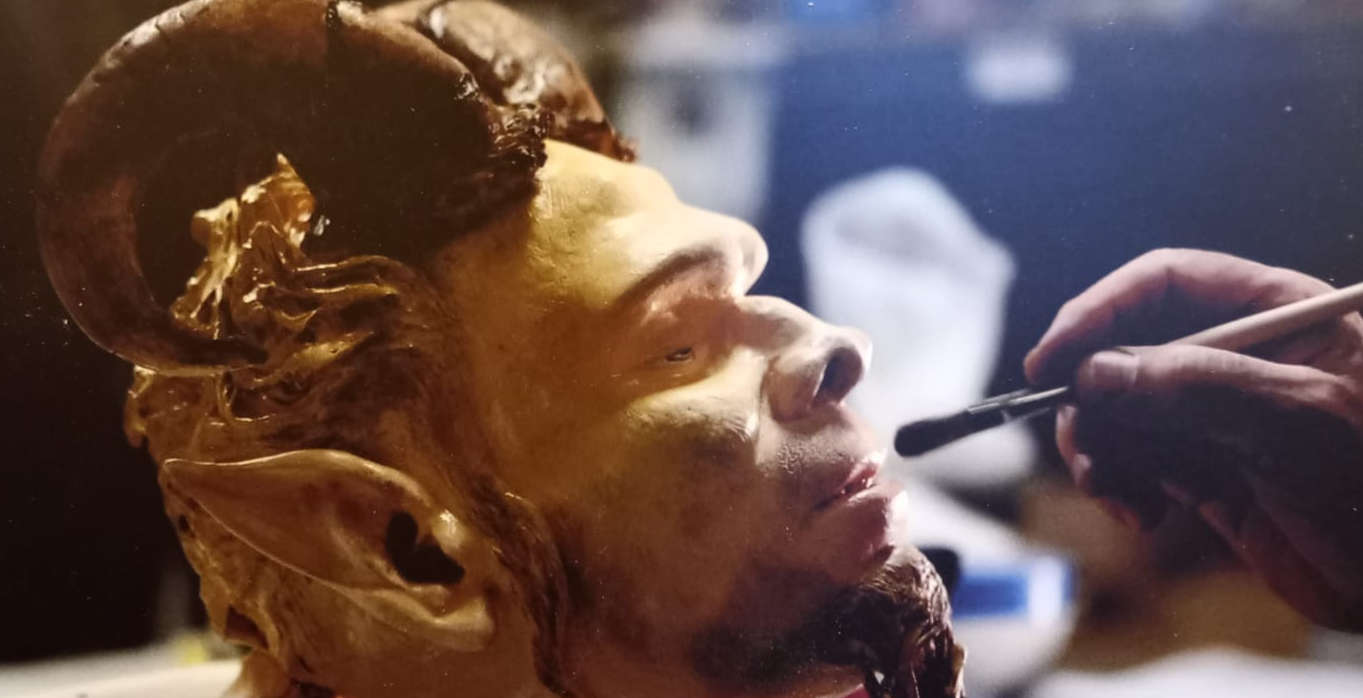

Bertozzi & Casoni’s faun committed suicide in the Rocca di Imola. We find it hanging in the southeastern keep, in a bare, square room, no outside view, an opening in the wall to let a little light filter through, minimal consolation. The last work on which Stefano Dal Monte Casoni worked before his untimely death, it was completed by Giampaolo Bertozzi, who thus concluded a work begun in 2000, from a vision, from a memory. The prodromes, in the 1980s, are those recounted by David Riondino: “they flew / to blue and red Pompeii, in the summer heat, which abducted them / in floral dances, carmine walls and slaves and ladies, / and mosaic fish and forests, wonder ships / that the great gray cloud one day buried, for us to find again. / The god Pan, from the painted forests of the red walls, watched them go, / and gave orders to the satyrs and nymphs to accompany them / into the porcelain treasury of Capodimonte: / baroque chandeliers, yellow and green and blue / triumph of the senses, living matter, passion and light.” Years later, fresh out of an exhibition in Turin, Stefano Dal Monte Casoni has like a vision, he too is summoned by something that resembles the voice shaking Thamus’ ship: to give concreteness to the vision of the faun’s suicide. “Can you imagine a faun hanging from a chandelier?” He says thus to Giampaolo Bertozzi. The idea was then in elaboration for years, fell asleep, awakened, on and off, then came back and became made pottery, and now the faun is there hanging in the damp of the Rocca Sforzesca in Imola, with the sun filtering through but not warming, with the sound of the wind stirring the foliage of the plane trees.

They called it The Death of Eros, although eroticism has little to do with it. It also has little to do with the essay Giuseppe Rensi had written in 1928, same title, references to Plato. There is, however, a kind of distant and common feeling: for Plato, eros is a vital force that moves the soul, drives human beings to understand truth; from eros descends philosophy. In the grand Dionysian theater of antiquity, Pan is often battling against Eros, understood as the god of love. But even to read it this way, without eros there is no longer any reason to live even for Pan. For Bertozzi & Casoni, eros is pure momentum, it is selfless passion, power of imagination, desire for beauty, desire for knowledge, healthy impulse, vital energy. “In Capodimonte we had seen fantastic chandeliers with leaves, flowers and painted landscapes, everything was immersed in a classical and romantic imagery, a world now lost, among ancient splendors, oriental-like discoveries, colorful parrots, fauns peeping through groves with bathing nymphs.” Bertozzi & Casoni’s faun chooses to hang himself right from a chandelier that gives visual concreteness to that varied and colorful world. It is a vision that surprises, because it comes unexpectedly as one enters the belly of the Rocca Sforzesca. A vision that disturbs, because Bertozzi & Casoni’simitatio seems more real than real, even if it gives life to their fantasy, and thus arouses a true astonishment, a baroque astonishment in the face of an unusual, unexpected, theatrical death. The faun is there inside the tower dangling bloodless, recently dead, the rope still in his hands, his eyes not yet fully closed, his mouth half-closed as if exhaling his last breaths.

Picasso, too, had made a faun die, in an illustration for a story by his friend Ramón Raventós, the story of a faun who inures and dies of grief for a dancer who chooses a human being instead. In Bertozzi & Casoni’s work, the suffering of the faun is universal. The death of eros is disillusionment, awareness that the passions have been extinguished, that the golden age no longer exists, the end of myth, the end of dreams, the end of everything. Dramatic realization that a world is gone and will not return. Awareness that the once young, eager, fertile world is now aged, debilitated, sick. The god realized this and took his own life. In the early twentieth century, Gaston La Touche, in one of his paintings with strong Symbolist overtones, much appreciated at the time, had imagined a different death for his faun, had him die in the midst of his woods, under a large tree, surrounded by companions, in a kind of pastoral elegy. Here, however, the faun dies in the solitude of a menacing, cramped, livid fortress, far from that wilderness where he has always lived, with no nymphs to mourn him, without even the comfort of his beasts.

Is the god therefore dead? D’Annunzio opened the Laudi with a shout, directed at everyone: peasants, women, children, old men, children of the sea. “Lied the voice before the toothed / Echinads thundering in the summer calm / Toward the ship.” He lied the voice that shouted to Thamus to make the announcement, and it is therefore up to him to sound another announcement, “Great Pan is not dead,” “and holy terror spread to the ends of the universe.” However, no one caught the announcement, no one trembled, no one seemed stunned. Did the faun then really die? Is that suicide real? Is it just a sham? Is it to be believed? Can gods really die?

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.